Guile Up To Date

The Strand Magazine, vol. 19, issue 114 (1900)

Pages 671-682

Introductory Note: As a short story that revolves around a peculiar criminal act, “Guile Up To Date” is well-suited for The Strand—a magazine aimed at middle-class families, renowned for its short story detective fiction like Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. Less action-packed than the Holmes stories and without a detective to fill the role of a lead character, however, “Guile Up To Date” allows readers space for a more subtle investigation of class differentiation, gender roles in the home, and the education of women. As such, the story presents a mixture of both crime fiction and social problem fiction.

I.

“UGH! what a night we’re going to have,” I said, as I put down the poker and stood in the warm glow, watching the flames and sparks from the logs fly up the wide chimney.

“Yes,” said my wife, raising her eyes from the embroidery she was at work upon, and looking so attractive in the ruddy glow that I stepped to her side and behaved as I did five years before—that is, in the winter before we were married.

“Don’t, Tony,” she said, smiling.

“Why not, pet?”

“Simmons might come in—or Jack.”

“Simmons had better not—a pompous old humbug! Hang him, he gives himself as many airs as if he were the squire and belonged to the Hall. As for Jack, he won’t be down for long enough. If he did appear he’d bolt, and come back looking solemn. We shall have the laugh of him soon.”

My wife coughed in a peculiar way.

“What does that mean?” I asked. “I say, Honor, you’re not quite so warm to Jack as you used to be before he proposed for Prue.”

“Indeed, I try to be, dear,” said my wife.

“Oughtn’t to want trying, pet. Jack’s a dear, good fellow, and you’ll own it when you know him better. I say, what a soaking he had this afternoon—drenched. He will go through everything, and he waded one ditch full of snow-water twice.”

“It is very foolish, dear,” said my wife, stitching away. “You men never seem to think of the risk of colds.”

“Of course not,” I replied, as I went to the window and looked out through the lattice casement at the wintry scene, with the snow whirling through the closing-in night. “B-r-r-r!” I growled, as I came back to the fire. “There’ll be no shooting to-morrow. Billiards all day, I expect. I say, dear, of course there’s not the slightest likelihood of Prue coming back by this afternoon’s train?”

“Not the slightest,” said my wife, quickly.

“Glad of it,” I said. “Be a horrible ride from the station through the snow and darkness. When is she coming?”

“The day after to-morrow, dear.”

“Well, it’s time she was back,” I grunted. “Here, put that work away! I want to talk to you, and you’re only hurting your dear old eyes.”

I snatched at the embroidery as I spoke, and my wife looked up uncomplainingly.

“What is it, dear?” she said, taking my hand.

I coughed now and hesitated, but her eyes seemed to make me speak.

“Well, I wanted to say a few words about Prue and Jack. Wasn’t it rather bad form for her to shoot off to London as soon as she knew Jack was coming down?”

“No, dear,” said my wife, slowly; “and it was not her doing.”

“What!” I cried.

“I sent her up, dear, to mamma for a week.”

“You did! What for?” I cried, in surprise.

“To do some shopping, for one thing.”

“And what was the other?”

“To be out of the way at first when Jack came.”

“The deuce you did!” I cried, in astonishment. “Why?”

“Because I did not want your cousin to find everything too smooth for him.”

“Well, of all——” I began.

“I am not quite convinced yet of Jack’s sincerity, dear,” said my wife, gravely, as she held my hand up to her cheek.

“My dear old girl!” I cried. “Shame!”

“Tony, dear,” she went on, as if she had not heard my words, “marriage is a very serious thing.”

“Of course, and the dearest and best thing in the world when a pair are well matched,” I cried, and I interpolated a little “business,” as theatrical people call it.

“Don’t, dear,” she said, again.

“Then don’t you set bad examples by rubbing my hand on your cheek. But I say, darling, to be serious, Jack is the best fellow in the world, and he loves Prue down to the ground.”

“He thinks he does, dear,” said my wife, quietly; “but he is very young and impulsive, and it would break my heart if he proved insincere to dear Prue.”

“I’d shoot the beggar if he did,” I cried, fiercely; “of course by accident, when aiming at a pheasant. Then you sent her away?”

“Yes, dear, and——Hush! here he is.”

For the drawing-room door opened, the portière was wafted inward, and the flames and sparks roared up the wide old chimney till the door was closed again, and my second cousin Jack, lieutenant of fusiliers, came in, looking as frank and handsome a young Englishman as could be met in a day’s march.1A portiere is a curtain hung over a door or doorway.

“I say, you two do look jolly in here,” he said, as he strode up to the fire.

“Yes; what a storm!” I cried. “All right and dry again?”

“Oh, quite; but I say, Mrs. Grange, wasn’t it lucky we had our shoot to-day?”

“Very,” said my wife, smiling.

“I say, though, you don’t think it likely your—your sister will come down to-night?”

“Not at all,” said my wife, as I, full of the late remarks, looked keenly at our visitor.

“I am glad,” he cried. “No, no, I mean I am sorry,” he added, hastily. “It isn’t a night fit for a dog to be out. What are you two laughing at?”

“You,” I said. “You don’t know your own mind.”

“Oh, don’t I?” he cried. “I meant to say, I wish she were here, but I shouldn’t like her to be travelling down in a storm like this.”

At that moment there was the sound of wheels muffled in the snow of the carriage drive, and a faint “Ck, ck, ck!” uttered by a driver.

“By George, here she is!” cried my cousin, springing from the chair into which he had sunk.

“Nonsense!” I cried. “Only something for the house.”

As I spoke the deep-toned clang of the door-bell was heard, followed in due course by the roar of the wind through the open hall door, and then by steps going and coming in the hall, and at intervals a couple of bumps.

I sought my wife’s eyes, and hers were fixed inquiringly upon mine, while Jack, who was all excitement, looked from one to the other again and again.

“I say,” he said, at last, “it must be Prue!”

“Stuff!” I cried, testily. “If it had been Prue she’d either have been in here by now or we should have been in the hall to meet her.”

“Yes, of course,” he cried; “but why aren’t you?”

“Because,” I said, “it is something for the servants or the house, or the book-box from the library, though why the deuce they have come up to the front door I-—here, what the dickens are you about?”

My words were too late to stop my cousin, for he was in the act of flinging open the door and rushing out, and before I could reach the hall myself I encountered him hurrying back, ready to thrust me before him into the drawing-room.

“It isn’t!” he said, in a sharp whisper. “But, by George! such a pretty girl!”

Before more could be said the door was re-opened by Simmons, our butler, just as the dull, muffled sound of wheels was again heard passing the window.

“Who has come, Simmons?” said my wife.

“The noo lady’s-maid, ma’am,” replied the butler, austerely.

“Halloa!” I cried. “I didn’t know of this. Have you discharged Robinson?”

“New lady’s-maid, Simmons?” said my wife. “Absurd! Oh, it is some mistake.”

“That’s what I told her, ma’am, but she said it was quite right: that she was engaged by a young lady at her ladyship’s in Eaton Street the day before yesterday.”

“By my sister?” said my wife, wonderingly.

“Yes’m. She said it was a handsome young lady with a very fresh colour.”

“Quite right,” said Jack, in a half whisper to me.

“And that she was wanted directly, ma’am, and the young lady gave her the money for her fare, and a card—one of our cards, ma’am—with the time on it the train left King’s Cross, and the station she was to get out at, and that she was to take the station fly and come on six miles. She’s brought her boxes, ma’am—two—heavy ones.”

“Then it isn’t a mistake,” I said. “There, take the poor thing to the housekeeper’s room, and tell them to give her some hot tea. She must be perished.”

“Yes, sir,” said the butler; and as soon as the door was closed I turned to my wife.

“Here, what game’s this?” I cried. “What does Prue want with a maid?”

“I don’t know, dear,” replied my wife. “I’m as much puzzled as you are. It is so strange. She never said a word to me.”

“You’ve offended her,” I said, meaningly. “You know why. She’s going away.”

“That’s it,” said Jack, eagerly. “I did write very plainly to her about something. I told her that at any time I might be ordered abroad, and begged her that something might take place at once.”

“And what did my sister say in her reply?” said my wife, stiffly.

“Oh, she wrote just what a girl would say,” cried Jack, laughing merrily—“that we must wait.”

“Of course,” said my wife, gravely. “My sister was not named Prudence for nothing, Mr. Merton.”

“Oh, come, none of that,” he cried. “It’s Jack, brother Jack, Mrs. Grange. I was a bit popped, as the Lincolnshire people call it, to find her away when I came. I didn’t like it, I can tell you. It seemed like huffing a fellow; but it’s all right. I see through it now. She’s been up to talk it over with the old girl.”

My wife is wonderfully like her sister, and they both have a beautiful high colour. In fact, I often chaff them both about it, and say what pretty girls they’d be if they were always kept in a cool place; but I never saw my wife’s cheeks so scarlet as they were that evening in the firelight when she drew herself up and said, haughtily:—

“My sister did not go up to town to consult mamma, Mr. Merton, and if she had gone for such a purpose, Lady Lancelot—the old girl!”—this was with withering contempt—“would not have given her consent to any such premature proceedings.”

“I beg pardon,” said Jack, hurriedly, in answer to several nods and shakes of the head from me. “No disrespect meant to Lady Lancelot. Nothing of the kind. Always feel chivalrous—as a soldier should, don’tcherknow, towards the—er—er—er mamma of the girl I’m engaged to, and of her sister. Really beg pardon, Mrs. Grange. Here, Tony, do help a fellow. You know: assure your wife I didn’t mean any harm.”

“Well,” I said, gruffly; “it’s not the way to speak of Lady Lancelot, Jack.”

“It wasn’t, old man,” he cried, warmly. “It wasn’t, indeed. It was blackguardly. Slipped out, don’tcherknow, Mrs. Grange—Honoria—sister—Prue’s sister—I say, do you want a fellow to go down upon his knees?”

“No,” said my wife, coldly. “Say no more about it, but pray dismiss that foolish idea from your brain.”

“But she went up to town directly after she must have had my letter saying I was coming down to stay. Why did she do that?” cried Jack, who was recovering his balance.

“Because I sent her,” said my wife, coldly.

“Oh!” said Jack, who was silenced for the moment. But he recovered himself and struck out again directly. “Look here,” he cried, in a tone of triumph; “then why did she engage such a pretty maid all in a hurry?”

“I do not know,” said my wife, crossing to the bell and pulling it sharply—a way she has when she feels nettled; “but let me tell you this, Mr. Merton: When your cousin was engaged to me he had no eyes for the prettiness of any maid-servant.”

“What!” cried Jack, bursting into a fit of uncontrollable merriment. “Oh, come!—I say!—I do like that!—Old Tony not have an eye for a pretty girl because he was engaged!—Why, he was–—”

“Will you hold your tongue, you confounded idiot!” I roared, for he paid not the slightest heed to my fierce grins and frowns.

“Halloa!” he cried. “What, have I done it again? Here, I suppose I’d better go to my room. Only send me up a cut of something, for I’m half starved.”

“You’d better!” I cried, in a rage. “Sit down, and hold your tongue.”

For at that moment Simmons answered the bell.

“Beg pardon, ma’am. I was coming up.”

“Why?” I asked, for the man was wide-eyed and trembling as if from excitement.

“The new young person’s coming, sir, and Miss Robinson.”

“What about Miss Robinson?” I cried.

“Fits, sir. Gone into hysterics. We couldn’t do anything with her at first, and I was going to ask you if Edward hadn’t better ride over to Lindthorpe for the doctor?”

“Tut, tut, tut!” exclaimed my wife. “When was she taken bad?”

“As soon as she heard there was to be a noo maid, ma’am.”

“Oh, dear me!” cried my wife. “It’s all a mistake, Simmons.”

“So I kep’ on telling her, ma’am; but she would shriek and throw herself about and say it was a shame, and that she’d go out and die in the snow. I haven’t sweat—perspired so, sir,” said the man, turning to me, “cold as it is, for a month.”

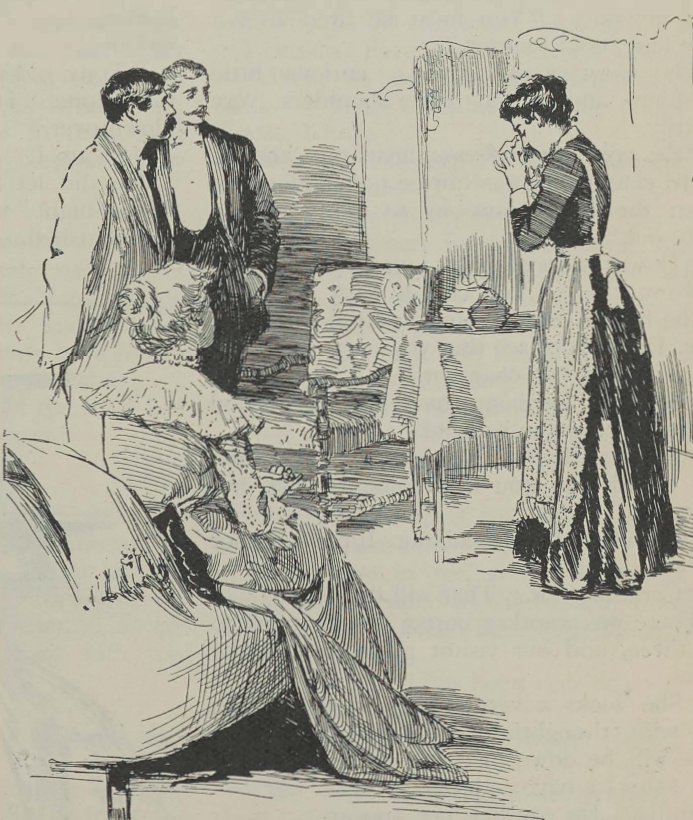

“I’ll come to her, Simmons,” said my wife.

“I don’t think you need now, ma’am. I got the best pale bottle out, and Mrs. Denham and cook nearly delooged her with it, and she’s calmed down now.”

“Then go and tell her, Simmons, that I say it is all a mistake, and that I am not going to dismiss her. Then, as soon as this strange person has finished her tea, bring her up here.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“One moment, Simmons. The station fly has not gone back, of course?”

“Oh, yes, ma’am. Parlow, the driver, went off in a hurry. He’d got to take Sir Rennery Rollins’s people to a dinner at Benby. Their brougham horse has got a cold.”2A brougham is a horse-drawn carriage with a roof, four wheels, and an open driver’s seat in front.

“That will do, Simmons,” said my wife.

“Beg pardon, ma’am; is cook to keep back the dinner?”

“No,” I said, sharply. “Mr. Merton’s starving.”

“Yes,” said my wife, sweetly. “You will not mind waiting another quarter of an hour—Jack?”

Her words brought my cousin to his feet, his face lighting up with satisfaction.

“Mind? Not I!” he cried, eagerly. “Only cut a little deeper, Tony, when you carve,” he added, turning to me.

II.

I LAUGHED, and as the butler left the room it was striking to see how we three all began to play at the game of making it up. Faces brightened, and we chattered away about every subject we could think of—the shooting that day—Jack’s wading the 2ft. deep ditch—the prospects for the morrow, and so on, but not a word about Prue or the new arrival till the door-handle rattled.

Then Jack sprang up.

“You’d like me to go?” he said, with a glance at my wife.

“Certainly not, Jack,” she replied, gravely. “Please stay.”

He dropped back into his lounge and stole a glance sidewise at the decidedly good-looking, refined, well-dressed body who was ushered into the room by Simmons, and who curtsied with quiet dignity to all three of us with one swoop as the door closed upon the butler.

In that one glance I saw that she had removed all trace of her journey, and that the little white lace cap she wore and her hair had quite a Parisian look, so that I was not surprised when, meeting my wife’s eyes, she gave a little affected start of surprise, and said, with a very French accent:—

“Ah, mamselle, then you have come first?”

“I—I beg your pardon?” said my wife, and Jack darted a knowing look at me.

“Mamselle told me avant hier that it would be some days before she came down into Lin-counne-sheere.”3Avant hier: French for “the day before yesterday.”

“It is a mistake,” said my wife, quietly. “I never saw you before in my life.”

“Mamselle!” said our visitor, in a tone of faint reproach, “when you tell me my lettre of raccommandacione from Miladi Rootlande are so sateesfactorre that you engage me at once, for it is an emairgencee?—— Ah-h-h! pardonne! No!” she cried, wrinkling her forehead with a piquante look of perplexity, as she raised her hands, palm outward, towards the dead gold brooch at her throat. “Eet is the same face, the same distingué air, and the same teint de rose in ze sheek.4Teint de rose: French for “rose complexion.” Pardonne, madame, you are ze seestairre?”

My wife bowed.

“Then my sister——”

“Mees Prudence Lanceleow,” said our visitor, smiling faintly.

“Engaged you for her maid?”

“Yes, madame, and the Lady Lanceleow.”

“Ah! you saw mamma?” said my wife, eagerly.

“Oh, oui, madame, and she ask me many question about my Lady Rootlande, and why I resign my dear good meestresse.”

“Why did you?” asked my wife.

“Ah, madame, she goes to live toujours, always, on the Riviera, and I can never see La Belle France any more.”

“Why?” I said, quickly, and then I repented speaking and interfering in my wife’s task, for our visitor turned her face slowly towards me, making several wrinkles in a very white forehead, and drawing up the inner ends of her eyebrows till they were quite straight, while she took a dainty cambric handkerchief from her pocket and applied it slowly to each of her eyes.

“Cet is too triste, m’sieu,” she said, in a low tone.5Triste: French for “sad.” “My fathaire—my brothaire! The teerrible days of the Commune! England is our countree now. I go back to beautiful France—nevaire.”

“I see; I see,” I said, hastily, and left my wife, as Jack said afterwards, to handle her cue.

“Did Lady Lancelot,” said my wife, “Lancelot; we pronounce the t’s—not Lancelo.”

“Ah, yais, madame: Launcelotte.”

“Did my mother ask you any further questions?”

“Oh, many, many, many, madame. About the coiffure, the robes, the dressmaking.”6A coiffure is a person’s hairstyle, typically an elaborate one.

“And was Lady Lancelot satisfied?”

“I think so, madame; but I remember she say to mamselle your seestairre a month on trial.”

“Yes; mamma would say so,” said my wife, thoughtfully.

“But mamselle your seestairre say that with such raccommandaciones it was not necessaire, as she was only in town for a day or two.”

“Ha!” sighed Jack, but he tried to cover it with a cough.

“But I forget, madame, she write to Miladi Rootlande, Hotel de Beau Rivage, Cannes.”

“Well, I will not detain you any longer,” said my wife. “You must be tired after a very long, cold journey.”

The new maid gave a curious little shudder, and raised her shoulders very prettily.

“Ze cold was affreuse, madame, and ze thirrd class coupé was vairree not comfortable when the hot wataire in ze foot-warm go quite out.”7Affreuse: French for “awful.”

“It was a long, cold journey,” said my wife. “You can go back to the housekeeper’s room, and tell Mrs. Denham to see that you have a fire in your bed-chamber.”

“Meeses Denham, madame—the good lady who have the bad fit?”

“No, no; that is Robinson, my maid. She was afraid that you had come to take her place.”

“Ah-h-h! I see, madame. But it ees not so.”

“Certainly not. That will do.”

There was another curtsy spread round to all three, and our visitor glided out of the room.

“She looks a very capable person,” said my wife, thoughtfully. “Then I suppose Prue will be down in a day or two; but we are sure to have a letter in the morning. Do you like her appearance, Tony?”

“Well, yes, but I always have a prejudice against those very precise-looking bodies. Not bad-looking, but a little old in the tooth. Eh, Jack?” I said, mischievously.

“Didn’t look at ‘em,” he replied, gruffly. “Dessay they’re false.”

I looked at my wife, and she looked at me, and then, quite at one, we all laughed merrily, our mirth being put an end to by the coming of Simmons, with—

“The dinner is served, ma’am.”

Then we adjourned to the dining-room, where the odour of soup and fish, and the brightness of fire, candles, plate and glass, made us all forget the coming of the new maid and the strange behavior of sister-in-law Prue.

That night, when Jack and I were in the smoking-room having our final cigars, my wife came in to bid our prospective relative good-night, and announced that it was snowing heavily.

“No shooting to-morrow, Jack,” she said, merrily.

“Never mind,” he replied, with his face lighting up. “I’ll have a good quiet day indoors.”

“Tony, old man,” he cried, as soon as we were alone, “I am glad that little breeze has blown over.”

“So am I. There, let it drop.”

He did let it drop, and we did not say “good-night” till another cigar had been lit and finished. Then I hurried up to our room, fully expecting to find my wife fast asleep; but ladies’ hair does take so long even on wintry nights, and she had not left her dressing-room.

“What have you done with the new maid?” I asked, after a time.

“Put her in the visitors’ servants’ room. Poor Robinson! She was half broken-hearted, and I’ve had to go and see her and comfort the silly girl.”

“But I say, Honor, is Jack right about Prue?”

“No,” said my wife, emphatically.

“Then what does it mean about the new maid?”

“I suppose she has taken it into her head to have one of her own. I don’t understand it yet, but let it wait till she comes back.”

“Strikes me you’ve put her monkey up by interfering between her and Jack.”

“No,” said my wife, after a few moments’ thought. “Prue felt with me that Jack ought to learn that he was not to treat their engagement so lightly. He has been acting over the most serious matter in their lives like a thoughtless boy. They cannot marry yet for years.”

“Certainly—”

Now, I have a vivid recollection of saying that word, and I meant to add not; but I don’t think I did, for all is blank in my mind till the regular hot-water knock came at our door, the necessary being brought by my wife’s maid.

It was Simmons who brought the other hot water, an hour later, over our meal.

III.

“WHAT a glorious morning!” was the favourite remark when we three gathered at the breakfast table, for the storm of the night was over, the sun shining brilliantly in a deep blue sky, and the whole world, as far as we could see, dazzling white with the heavy snowfall.

“Slept well, Jack?” I said.

“Never better. Wind seemed to sing lullaby.”

“Yes, Simmons?” I said, as that worthy’s lips moved preliminary to a speech as he handed the cutlets.

“I beg pardon, sir, but did either of you gentlemen open the front door after I had gone to bed?”

“Swear I didn’t,” said Jack, with his mouth full of hot bread-cake.

“No, certainly not,” I replied. “Why, did you think you heard it?”

“No, sir; but all the fastenings were undone, and the bar standing in the corner.”

“Halloa!” cried Jack; “burglars. What about the plate-chest, Simmons?”

“That’s quite safe, sir, in the iron closet,” said the butler, shaking his head. “It would be a bad night’s work for any burglar, sir, who came near my pantry.”

“Yes, you’d better remember that while you’re stopping here, old man, and not go rousing him up in the night. Ring your bedroom bell if you want B. and S., or anything of that kind. Simmons has a brace of pistols over his bed’s head—a fine old pair of flint-locks that were at Waterloo.”

I’ll remember,” said Jack, devoting himself attentively to the cutlets.

“You must have forgotten to fasten the hall door, Simmons,” I said, rather sternly.

“I bed your pardon, sir,” said the butler, severely, and with a movement of the head which made his stiff white neckcloth crackle. “I couldn’t have gone to sleep if I had.”

“Well, no one here meddled with it,” I said. “There’s nothing wrong about the house, I hope?”

“No, sir, nothing. I have examined all the lower windows.”

“Ah, but what about the upper?”

“The gardeners have been round, sir, and there’s not a sign outside, and the ladders are all in their shelter on the barn wall.”

“What about footmarks?”

“The ground’s one thick sheet of snow, sir. There wasn’t a footprint.”

“False alarm, Simmons,” I said. “One of the maids must have unfastened the door before you were up.”

“But I beg——”

“Well, never mind till after breakfast,” I said. “Where’s the letter-bag?”

“Not come in yet, sir. I hear that the mail’s been stopped by the snow in a cutting, and the road between here and the station’s quite blocked.”

“Then the fall has been very heavy?”

“Tremenjus, sir.”

No more was said, the butler leaving the room.

“We must have had a storm, then,” said Jack, glancing out at the dazzling white landscape.

“Yes; no shooting to-day, Jack,” said my wife.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said. “I vote we go after the hares, Tony. We can see them a mile away, and track them by the footprints.”

“Rather murderous, eh?” I ventured to observe.

“Oh, no; we won’t shoot many. It will be glorious out in the snow.”

“Very well,” I said. “How soon shall we start?”

“Soon as you like, old man. I’ll get my leggings on and go round the house to see how deep the snow is. Ah! they’re shoveling away on the drive.”

“Yes,” I said, as we all adjourned to the big bay window. “My word, it is deep!”

Just then Simmons re-entered.

“Mrs. Denham would like to speak to you, ma’am, when you have done breakfast.”

“We’ve quite finished, Simmons,” replied my wife. “Is it about the new maid?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Send her in.”

“Here, I say,” I cried, as the butler left the room; “I hope that woman’s not knocked up with her journey and wants a doctor.”

Our prim old housekeeper entered the room directly, looking very much troubled, and after her salutes to all, began with:—

“I’m very sorry to trouble you, ma’am, but the new French maid—”

“I knew it, Jack,” I cried. “What do you say to me for a prophet?”

“You knew it, Master Anthony?” cried the old lady, eagerly, addressing me after her familiar fashion, begun in my late father’s days.

“Yes. What is it—feverish cold from exposure? Well, you can doctor her for that: Dover’s powder, mustard plaster, and all the rest of it.”

“But she’s gone, sir!” said the old lady, excitedly.

“Gone!” we all cried, in a breath.

“Yes, ma’am. Yes, Master Anthony. Her door was locked, and we couldn’t make her hear, and I consulted with Mr. Simmons, and we decided at last to break the lock.”

“And you did?” I cried, excitedly.

“Yes, sir, and found the bed had not been slept in, but the fire had been kept up so that the scuttle was empty; and some time in the night she must have slipped away.”

“What, through that storm?”

“Yes, sir. Mr. Simmons found the hall-door unfastened. She must have come down and let herself out.”

“Strange,” I said. “But what about her boxes?”

“They’re both in the room, sir, just as John left them after he and the boy had carried them up and uncorded one and unstrapped the other for her.”

“Then she has taken fright,” I said, decidedly. “Didn’t like the look of us; and the next thing will be an application for her boxes.”

“But what about Prue when she comes down?” cried Jack. “She’ll be horribly disappointed. I say,” he continued, turning to my wife, “you didn’t tell the woman that she couldn’t stay, or anything of that sort?”

“No, no; I did not see her again, Jack,” said my wife.

“Here, stop a minute,” I cried. “Is all right upstairs?”

“Oh, Tony, dear; don’t be so cruelly suspicious,” cried my wife. “It is as you say: The poor, excitable Frenchwoman has taken fright. Everything is quite correct upstairs, Denham?”

“Yes, ma’am, as far as I could make out,” replied the old housekeeper.

“Did you look round my dressing-room?”

“Oh, yes, ma’am.”

“And my jewel-case was on the escritoire?”8An escritoire is a small writing desk with drawers and compartments.

The old woman’s jaw dropped, and with a faint cry my wife darted towards the door, all following, and reaching the hall in time to see her disappear at the top of the great flight of broad oak stairs.

They were very low, broad stairs, and I went up them four at a time, reaching the dressing-room door just in time to hear my wife shriek loudly, and to meet her as she rushed out.

“Oh, Tony, all my diamonds and pearls—all my best wedding presents!”

“D—n!” I shouted.

“Sold!” cried Jack, his word sounding like an echo from the landing.

I ask pardon for using the first of these words, but I place them here just to show how emphatic Englishmen can be at a critical time, and also how with one word they can express as much as a Frenchman would require at least a hundred to effect.

“Yes,” cried my wife, excitedly; “I see it all now.”

“Oh, yes, my dear; we can see it all now,” I said, bitterly. “it’s perfectly plain, and, as Jack says, we’ve been sold.”

“Well, look here,” cried Jack; “now’s the time to show your administrative powers, Tony; and I’ll do the executive.”

“What do you mean?” I said, savagely.

“Order out your light cavalry to summon the police, and put a stopper on anyone going off by rail from any station within a radius of twenty miles round.”

“Hurrah! Good!” I cried, as my brain began to work.

“Then wire off to Prue. No, I’ll do that, and answer paid.”

“Yes, do, Jack,” I cried. “And, look here, the line’s blocked. She—the enemy—can’t have got away. Go and write your wire. I’ll have the horses saddled and the men off for the police, while you and I will search the country round.”

“Yes, dear; do, do, do—oh, do!” cried my wife. “I would not lose those presents for ten times their value. Oh, to think I could have let myself be deceived like that!”

We all set to work, and in a very short time the men were struggling through the snow-drifts on their way to town and station, while with the help of the three gardeners and the boy we went wading about the grounds and the road and lanes beyond, to find out in a very short time that we could do nothing for the snow, and, of course, there was not a track to be seen.

“Look here,” I said, as we encountered my head gardener after a long round, “when did it begin to snow hard?”

“Four o’clock, sir. Then it came all at once.”

“How do you know?”

“I was in a bit of a fidget, sir, about my stove plants and my fires, for I felt that a big change was coming, and I couldn’t sleep. I was out twice to put on more coke, and it was four by my clock in the bothy when I came back the second time, with the snow coming down blinding, sir.”9A bothy is a basic shelter but is also a common term for a basic accommodation, usually for gardeners or other workers on an estate.

“Earlier in the night there was not so much snow?”

“No, sir; it melted away as it fell.”

“Then she must have got away before the storm came on.”

“I’m afraid so,” replied Jack. “Here, hadn’t we better get back to the Hall to see if there’s any news?”

I nodded, and we trudged back through the snow, to find that the letter-bag and a telegram had been brought in, the mail-cart having arrived from a town twenty miles away.

“I opened your telegram, Jack,” said my wife, apologetically, as she handed it to him.

“That’s right. What does she say? Oh, here it is: ‘All stuff and nonsense. I have engaged no maid. Coming down by the next train’!”

“Of course she hadn’t,” cried my wife, triumphantly, and Jack crumpled up the pink paper and stood rubbing his ear with a corner, looking vexed and upset.

“Oh, dear, oh, dear! My diamonds—my pearls!” sobbed my wife.

“Don’t, don’t, don’t! I cried, querulously. “I’ll buy you some more.”

“But you can’t buy those again, Tony. Oh! that wicked, deceitful woman!”

“Be quiet,” I said; “here’s the inspector’s cart, and the majesty of the law.”

A few minutes later the official was being put in possession of all we knew, and he nodded his head and looked wonderfully wise.

“There’s no doubt about it, sir,” he said, at last. “You’ve been regularly had, and our only chance to catch my lady somewhere on the rail. She’s gone north, and as soon as I get back to the station I’ll have the wires at work. But I should just like to see her boxes.”

“This way,” I said, and we all went up to the neat bedroom reserved for the servants of our visitors, on one side of which stood a big, oak-painted, iron travelling box and one of the regular, half-round-topped, shiny, black canvas trunks so much affected by woman-kind.

“Quite noo uns,” said the inspector. “Can you oblige me with a screwdriver and hammer, Mr. Simmons?”

The butler hurried off to fetch the tools, and my wife interposed.

“Would it be right to break open a servant’s boxes?” she said.

“Under special circumstances, madam,” said the inspector, gravely; “and these are very special.”

“Of course,” I said; and as soon as Simmons returned the inspector dexterously inserted the edge of the big screwdriver.

“Why, you seem to know how to do it,” said Jack.

“Yes, sir; took lessons from the gentlemen of the jemmy,” replied the inspector; and crick! crack! up flew the lid.10A jemmy is a short crowbar used by a burglar to force open a window or door.

“Thought so,” he said. “Bricks packed tightly in hay. Same in the other, I’ll be bound.”

He was quite right; and all new—boxes, bricks, and hay.

“My lady expected to make a good haul, sir,” said the inspector, “so didn’t spare expense. At what sum would you value the jewels?”

“Five thousand pounds, at least,” I said. “Old family diamonds and presents.”

“Then I’ll be off, sir, at once,” said the inspector, “and I’ll send you news the moment there is anything to say.”

We could do no more than arrange for the brougham to fetch Prue that evening, for if the line was cleared she would be at the station at seven; and the day wore on, full of expectation, but with no news.

When the time came my wife decided to go in the brougham herself to fetch her sister, making Jack look rather glum; but he said nothing, only smoked a great deal, and stood for the last half-hour outside the hall door, while he waited for the return of the brougham.

This came in due time, Prue looking exceedingly bright and attractive, and in true sisterly fashion doing all she could to comfort my wife over her loss.

Then in spite of the trouble as the night wore on I saw enough to prove to me, as I said later on to my wife, that it was no matter what she or I said or did, matters between the young people would have to take their course. For whatever his failings might be, Jack was passionately in love with Prue, and the young lady herself looked upon him as a perfect hero and all that was desirable in a man.

At breakfast next morning Honor and I were late, and my wife looked a trifle serious and annoyed to find that “the young people” had been down for an hour and a half, talking by the fire.

“Yes,” said Prue, quietly; “it had only just been lit when I came down.”

“I never looked upon you as an early riser, Prue,” said my wife, rather coldly.

“You were down pretty soon too, Jack,” I said, drawing a bow at a venture.

“Oh, yes; I was first,” said our visitor, innocently. “We planned it last night.”

“Planned what?” said my wife, sharply.

“To hold a meeting about your loss,” said Jack; “and we agreed to this, that as Prue’s got £5,000 of her own when she marries, she shall hand it over to you to replace your jewels.”

“Oh!” cried my wife, with the tears rising to her eyes.

“It’s all right, Mrs. Grange; we’ve settled it all. We don’t want the money, do we, Prue?”

“No, Jack, dear,” she said, going behind him to lay her hands on his shoulders—both of which little pink bunches of fingers he prisoned and then kissed. “We only want one another.”

“Oh, spoons!” I cried, savagely. “Sweet children! Of course, you don’t want any money, only bread, and honey, and moonshine. Bah!”

“Be quiet, Tony,” said my wife, with the tears gathering thickly; and the next minute she made both their faces wet by bending down and kissing them, her lids brimming over in the act.

“Not of a penny of it, Prue, dear,” she said. “But it’s very nice and manly of you, Jack, dear, and I shall never forget it. There, I won’t fret about a few bits of coloured stone and gold and silver, and I won’t oppose anything again if you’ll both promise to be a good boy and girl and wait for a year.”

“A year!” cried Jack, in a tone of dismay.

“Pst! Simmons!” I whispered, and then aloud, “What have you got?”

“Kidneys, sir.”

“Devilled?”

“Yes, sir; and fried soles.”11A sole is a species of flatfish.

“Then come along, good folks; it’s nearly ten.”

“Ha, yes,” cried Jack, taking his chair, with the love-light in his eyes giving place to a fierce, ravening look indicative of hunger.

But he looked very genial half an hour later when he turned to me.

“I say, Tony, old man,” he cried, “what are we going to do to-day?”

“I’m going to ride over to the station and try to get news of that wretched woman.”

“No, Tony,” said my wife, decisively; “nothing of the kind. The matter is in the hands of the police, and if my jewels are found I shall be very glad; but if they prove to be lost they are lost, and I shall not fret about them.”

“Oh!” I said. “So much for what I’m going to do. I’ll try again about you, Jack. You’re going to lie down like a lap-dog at Prue’s feet, and blink, and beam, and worship, and-—”

“That I’m not,” he shouted. “Prue doesn’t want me to be such a fool in public.”

“But in private?”

“You mind your own business,” growled Jack. “You’ve got a wife. Look here—the hares are scuffling about all over the snow; I must go and have a turn at them to-day. Never mind the robbery; come on.”

“Yes, Tony, dear; don’t let that trouble put a stop to your going out.”

“Oh, very well,” I said, and we started, with the understanding that we were to be back to a late luncheon at two o’clock.

We came back earlier. For after a tramp over the frozen snow we found ourselves about a mile from home, with the keeper and a couple of retrievers panting at our side. We were making for a hazel copse dotted with good-sized oak trees, the keeper having given it as his opinion that we should put up a pheasant or two where the snow lay less thick, and that the dogs would flush them at the lower end.

But we shot no pheasant, for about half-way through the copse one of the dogs gave tongue and rushed off, to begin scratching eagerly and snuffling in a hollow half-filled with snow.

“Halloa!” cried Jack, as we came up. “What’s he got here?”

“Rabbit,” I said, contemptuously; “come away, you brute.—Here, both of you,” I cried, excitedly; “look sharp. Good heavens, Jack! Some poor creature has been overtaken in the storm.”

“Dead?” gasped Jack, as he leaned over the hollow from which, after casting aside our guns, we had scraped away the snow.

“Yes. She must have been here since the night before last. Why, Jack, it is that woman!”

The figure lay curled up in a crouching attitude, wrapped in a large waterproof, and with a woollen check scarf drawn over her head and face.

I thrust my hand beneath the scarf to try and find whether there was a trace of life, and sure enough there was a little warmth, and one of the arms upon which I drew to get at the throat yielded.

“Here, Jack,” I cried, excitedly, “never mind the guns. Where’s your flask?”

This was produced, and when a few drops were poured between the blue lips we saw them trickle in through the clenched teeth and disappear, to be followed by a spasmodic contraction of the throat.

“She’s alive yet,” I said. “Now then, come along; let’s get her back to the Hall. What have you got there, Thomson?”

“Sort of box, sir, with a strap round it,” said the gamekeeper, brushing off the snow from something against which he had kicked.

“Why, Tony, old man, it’s the jewel-case,” cried Jack, excitedly. “Talk about bagging game: we’ve done it this time!”

He was quite right, and though we left our guns behind, with the dogs to watch, we contrived to carry my wife’s jewel-case as well as our prisoner back to the Hall—the latter part of the journey being lightened by means of help from the gardeners, who were fetched, and brought a hand-barrow.

Everything possible was done when we arrived at the house, and by the time the doctor reached us from the town our visitor was beginning to display signs of life.

Let it suffice to say that after a long fit of rheumatic fever, during which the woman was well nursed, she was transferred to the infirmary in the county gaol, and from thence went before the magistrates and afterwards for trial—a trial which resulted in a couple of years’ imprisonment.12“Gaol” is the British version of the American word “jail.”

There was no mystery in the case after all, for Prue identified the woman at once as an out-of-place French servant who had been in the habit of visiting one of her mother’s maids in Eaton Street, and from what she had picked up there the woman managed to plan the theft which so nearly succeeded.

“It was as clever as it was daring, sergeant,” I said to the detective who had had charge of the case.

“Yes, sir,” he said, “pretty tidy; but you see it was a woman, and you never know where to have them. The artfulness some of ‘em’s got in their heads, and the face with which they carry it out, is something that caps me. We have to keep our eyes open to be on a level with the men nowadays, for the more folks of their sort are educated the cunninger they grow. I always want to know what they’ll be up to next. But when it comes to a woman—there, I’m done!”

Original Document

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

George Manville Fenn. “Guile Up To Date.” The Strand Magazine, vol. 19, no. 114, 1900, pp. 671-82. Edited by Joshua Richardson. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 18 April 2024, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/guile-up-to-date/.

Editors

Joshua Richardson

McKenna Rice

Cosenza Hendrickson

Eden Buchert

Posted

19 March 2020

Last modified

18 April 2024

Notes

| ↑1 | A portiere is a curtain hung over a door or doorway. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A brougham is a horse-drawn carriage with a roof, four wheels, and an open driver’s seat in front. |

| ↑3 | Avant hier: French for “the day before yesterday.” |

| ↑4 | Teint de rose: French for “rose complexion.” |

| ↑5 | Triste: French for “sad.” |

| ↑6 | A coiffure is a person’s hairstyle, typically an elaborate one. |

| ↑7 | Affreuse: French for “awful.” |

| ↑8 | An escritoire is a small writing desk with drawers and compartments. |

| ↑9 | A bothy is a basic shelter but is also a common term for a basic accommodation, usually for gardeners or other workers on an estate. |

| ↑10 | A jemmy is a short crowbar used by a burglar to force open a window or door. |

| ↑11 | A sole is a species of flatfish. |

| ↑12 | “Gaol” is the British version of the American word “jail.” |