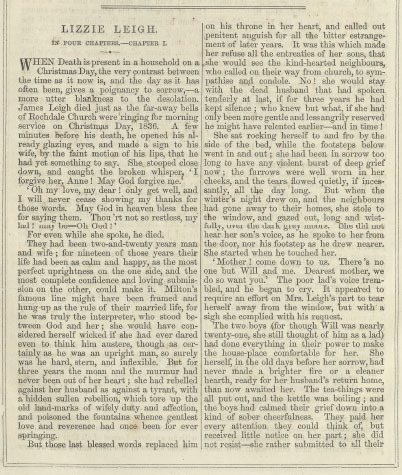

Lizzie Leigh, Part 3

Household Words: A Weekly Journal, vol. 1, issue 3 (1850)

Pages 60-65

Introductory Note: Elizabeth Gaskell had already earned recognition as the author of the industrial novel Mary Barton when she was recruited by Charles Dickens to write for his new periodical, Household Words. “Lizzie Leigh” was published in three installments in the journal’s first three issues.

Like Mary Barton, “Lizzie Leigh” is set in Manchester. It tells the story of a mother from the countryside who moves to the city in a desperate search for her only daughter, Lizzie. In this story, Gaskell teaches readers to have sympathy for Lizzie—a woman who is ostracized by traditional Victorian society.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the third of three parts:

Chapter III.

That night Mrs. Leigh stopped at home; that only night for many months. Even Tom, the scholar, looked up from his books in amazement; but then he remembered that Will had not been well, and that his mother’s attention having been called to the circumstance, it was only natural she should stay to watch him. And no watching could be more tender, or more complete. Her loving eyes seemed never averted from his face; his grave, sad, care-worn face. When Tom went to bed the mother left her seat, and going up to Will where he sat looking at the fire, but not seeing it, she kissed his forehead, and said,

‘Will! lad, I’ve been to see Susan Palmer!’

She felt the start under her hand which was placed on his shoulder, but he was silent for a minute or two. Then he said,

‘What took you there, mother?’

‘Why, my lad, it was likely I should wish to see one you cared for; I did not put myself forward. I put on my Sunday clothes, and tried to behave as yo’d ha’ liked me. At least I remember trying at first; but after, I forgot all.’

She rather wished that he would question her as to what made her forget all. But he only said,

‘How was she looking, mother?’

‘Well, thou seest I never set eyes on her before; but she’s a good gentle looking creature; and I love her dearly, as I’ve reason to.’

Will looked up with momentary surprise; for his mother was too shy to be usually taken with strangers. But after all it was natural in this case, for who could look at Susan without loving her? So still he did not ask any questions, and his poor mother had to take courage, and try again to introduce the subject near to her heart. But how?

‘Will!’ said she (jerking it out, in sudden despair of her own powers to lead to what she wanted to say), ‘I telled her all.’

‘Mother! you’ve ruined me,’ said he standing up, and standing opposite to her with a stern white look of affright on his face.

‘No! my own dear lad; dunnot look so scared, I have not ruined you!’ she exclaimed, placing her two hands on his shoulders and looking fondly into his face. ‘She’s not one to harden her heart against a mother’s sorrow. My own lad, she’s too good for that. She’s not one to judge and scorn the sinner. She’s too deep read in her New Testament for that. Take courage, Will; and thou mayst, for I watched her well, though it is not for one woman to let out another’s secret. Sit thee down, lad, for thou look’st very white.’

He sat down. His mother drew a stool towards him, and sat at his feet.

‘Did you tell her about Lizzie, then?’ asked he, hoarse and low.

‘I did; I telled her all! and she fell a crying over my deep sorrow, and the poor wench’s sin. And then a light comed into her face, trembling and quivering with some new glad thought; and what dost thou think it was, Will, lad? Nay, I’ll not misdoubt but that thy heart will give thanks as mine did, afore God and His angels, for her great goodness. That little Nanny is not her niece, she’s our Lizzie’s own child, my little grandchild.’ She could no longer restrain her tears, and they fell hot and fast, but still she looked into his face.

‘Did she know it was Lizzie’s child? I do not comprehend,’ said he, flushing red.

‘She knows now: she did not at first, but took the little helpless creature in, out of her own pitiful loving heart, guessing only that it was the child of shame, and she’s worked for it, and kept it, and tended it ever sin’ it were a mere baby, and loves it fondly. Will! won’t you love it?’ asked she beseechingly.

He was silent for an instant; then he said, ‘Mother, I’ll try. Give me time, for all these things startle me. To think of Susan having to do with such a child!’

‘Aye, Will! and to think (as may be yet) of Susan having to do with the child’s mother! For she is tender and pitiful, and speaks hopefully of my lost one, and will try and find her for me, when she comes, as she does sometimes, to thrust money under the door, for her baby. Think of that, Will. Here’s Susan, good and pure as the angels in heaven, yet, like them, full of hope and mercy, and one who, like them, will rejoice over her as repents. Will, my lad, I’m not afeard of you now; and I must speak, and you must listen. I am your mother, and I dare to command you, because I know I am in the right and that God is on my side. If He should lead the poor wandering lassie to Susan’s door, and she comes back crying and sorrowful, led by that good angel to us once more, thou shalt never say a casting-up word to her about her sin, but be tender and helpful towards one “who was lost and is found,” so may God’s blessing rest on thee, and so mayst thou lead Susan home as thy wife.’1Quote from Luke 15:32.

She stood no longer as the meek, imploring, gentle mother, but firm and dignified, as if the interpreter of God’s will. Her manner was so unusual and solemn, that it overcame all Will’s pride and stubbornness. He rose softly while she was speaking, and bent his head as if in reverence at her words, and the solemn injunction which they conveyed. When she had spoken, he said in so subdued a voice that she was almost surprised at the sound, ‘Mother, I will.’

‘I may be dead and gone,—but, all the same,—thou wilt take home the wandering sinner, and heal up her sorrows, and lead her to her Father’s house. My lad! I can speak no more; I’m turned very faint.’

He placed her in a chair; he ran for water. She opened her eyes, and smiled.

‘God bless you, Will. Oh! I am so happy. It seems as if she were found; my heart is so filled with gladness.’

That night Mr. Palmer stayed out late and long. Susan was afraid that he was at his old haunts and habits,—getting tipsy at some public-house; and this thought oppressed her, even though she had so much to make her happy, in the consciousness that Will loved her. She sat up long, and then she went to bed, leaving all arranged as well as she could for her father’s return. She looked at the little rosy, sleeping girl who was her bed-fellow, with redoubled tenderness, and with many a prayerful thought. The little arms entwined her neck as she lay down, for Nanny was a light sleeper, and was conscious that she, who was loved with all the power of that sweet childish heart, was near her, and by her, although she was too sleepy to utter any of her half-formed words.

And by-and-bye she heard her father come home, stumbling uncertain, trying first the windows, and next the door-fastenings, with many a loud incoherent murmur. The little Innocent twined around her seemed all the sweeter and more lovely, when she thought sadly of her erring father. And presently he called aloud for a light; she had left matches and all arranged as usual on the dresser; but, fearful of some accident from fire, in his unusually intoxicated state, she now got up softly, and putting on a cloak, went down to his assistance.

Alas! the little arms that were unclosed from her soft neck belonged to a light, easily awakened sleeper. Nanny missed her darling Susy, and terrified at being left alone in the vast mysterious darkness, which had no bounds, and seemed infinite, she slipped out of bed, and tottered in her little night-gown towards the door. There was a light below, and there was Susy and safety! So she went onwards two steps towards the steep abrupt stairs; and then dazzled by sleepiness, she stood, she wavered, she fell! Down on her head on the stone floor she fell! Susan flew to her, and spoke all soft, entreating, loving words; but her white lids covered up the blue violets of eyes, and there was no murmur came out of the pale lips. The warm tears that rained down did not awaken her; she lay stiff, and weary with her short life, on Susan’s knee. Susan went sick with terror. She carried her upstairs, and laid her tenderly in bed; she dressed herself most hastily, with her trembling fingers. Her father was asleep on the settle downstairs; and useless, and worse than useless if awake. But Susan flew out of the door, and down the quiet resounding street, towards the nearest doctor’s house. Quickly she went; but as quickly a shadow followed, as if impelled by some sudden terror. Susan rang wildly at the night-bell,—the shadow crouched near. The doctor looked out from an upstairs window.

‘A little child has fallen down stairs, at No. 9 Crown-street, and is very ill,—dying I’m afraid. Please, for God’s sake, sir, come directly. No. 9 Crown-street.’

‘I’ll be there directly,’ said he, and shut the window.

‘For that God you have just spoken about,—for His sake,—tell me are you Susan Palmer? Is it my child that lies a-dying?’ said the shadow, springing forwards, and clutching poor Susan’s arm.

‘It is a little child of two years old,—I do not know whose it is; I love it as my own. Come with me, whoever you are; come with me.’

The two sped along the silent streets,—as silent as the night were they. They entered the house; Susan snatched up the light, and carried it upstairs. The other followed.

She stood with wild glaring eyes by the bedside, never looking at Susan, but hungrily gazing at the little white still child. She stooped down, and put her hand tight on her own heart, as if to still its beating, and bent her ear to the pale lips. Whatever the result was, she did not speak; but threw off the bed-clothes wherewith Susan had tenderly covered up the little creature, and felt its left side.

Then she threw up her arms with a cry of wild despair.

‘She is dead! she is dead!’

She looked so fierce, so mad, so haggard, that for an instant Susan was terrified—the next, the holy God had put courage into her heart, and her pure arms were round that guilty wretched creature, and her tears were falling fast and warm upon her breast. But she was thrown off with violence.

‘You killed her—you slighted her—you let her fall down those stairs! you killed her!’

Susan cleared off the thick mist before her, and gazing at the mother with her clear, sweet angel-eyes, said mournfully—

‘I would have laid down my own life for her.’

‘Oh, the murder is on my soul!’ exclaimed the wild bereaved mother, with the fierce impetuosity of one who has none to love her and to be beloved, regard to whom might teach self-restraint.

‘Hush!’ said Susan, her finger on her lips. ‘Here is the doctor. God may suffer her to live.’

The poor mother turned sharp round. The doctor mounted the stair. Ah! that mother was right; the little child was really dead and gone.

And when he confirmed her judgment, the mother fell down in a fit. Susan, with her deep grief, had to forget herself, and forget her darling (her charge for years), and question the doctor what she must do with the poor wretch, who lay on the floor in such extreme of misery.

‘She is the mother!’ said she.

‘Why did she not take better care of her child?’ asked he, almost angrily.

But Susan only said, ‘The little child slept with me; and it was I that left her.’

‘I will go back and make up a composing draught; and while I am away you must get her to bed.’

Susan took out some of her own clothes, and softly undressed the stiff, powerless form. There was no other bed in the house but the one in which her father slept. So she tenderly lifted the body of her darling; and was going to take it down stairs, but the mother opened her eyes, and seeing what she was about, she said,

‘I am not worthy to touch her, I am so wicked; I have spoken to you as I never should have spoken; but I think you are very good; may I have my own child to lie in my arms for a little while?’

Her voice was so strange a contrast to what it had been before she had gone into the fit that Susan hardly recognised it; it was now so unspeakably soft, so irresistibly pleading, the features too had lost their fierce expression, and were almost as placid as death. Susan could not speak, but she carried the little child, and laid it in its mother’s arms; then as she looked at them, something overpowered her, and she knelt down, crying aloud,

‘Oh, my God, my God, have mercy on her, and forgive, and comfort her.’

But the mother kept smiling, and stroking the little face, murmuring soft tender words, as if it were alive; she was going mad, Susan thought; but she prayed on, and on, and ever still she prayed with streaming eyes.

The doctor came with the draught. The mother took it, with docile unconsciousness of its nature as medicine. The doctor sat by her; and soon she fell asleep. Then he rose softly, and beckoning Susan to the door, he spoke to her there.

‘You must take the corpse out of her arms. She will not awake. That draught will make her sleep for many hours. I will call before noon again. It is now daylight. Good-bye.’

Susan shut him out; and then gently extricating the dead child from its mother’s arms, she could not resist making her own quiet moan over her darling. She tried to learn off its little placid face, dumb and pale before her.

“Not all the scalding tears of care

Shall wash away that vision fair;

Not all the thousand thoughts that rise,

Not all the sights that dim her eyes,

Shall e’er usurp the place

Of that little angel-face.”2An excerpt from Barry Cornwall’s poem, “On the Portrait of a Child,” from The Prose and Poetry of Europe and America: Consisting of Literary Gems and Curiosities, and Containing the Choice and Beautiful Productions of Many of the Most Popular Writers of the Past and Present Age, Ed. G. P. Morris and N. P. Willis, New York: Leavitt & Allen, 1845, 581.

And then she remembered what remained to be done. She saw that all was right in the house; her father was still dead asleep on the settle, in spite of all the noise of the night. She went out through the quiet streets, deserted still although it was broad daylight, and to where the Leighs lived. Mrs. Leigh, who kept her country hours, was opening her window shutters. Susan took her by the arm, and, without speaking, went into the house-place. There she knelt down before the astonished Mrs. Leigh, and cried as she had never done before; but the miserable night had overpowered her, and she who had gone through so much calmly, now that the pressure seemed removed could not find the power to speak.

‘My poor dear! What has made thy heart so sore as to come and cry a-this-ons? Speak and tell me. Nay, cry on, poor wench, if thou canst not speak yet. It will ease the heart, and then thou canst tell me.’

‘Nanny is dead!’ said Susan. ‘I left her to go to father, and she fell down stairs, and never breathed again. Oh, that’s my sorrow! but I’ve more to tell. Her mother is come—is in our house! Come and see if it’s your Lizzie.’ Mrs. Leigh could not speak, but, trembling, put on her things, and went with Susan in dizzy haste back to Crown-street.

Chapter IV.

As they entered the house in Crown-street, they perceived that the door would not open freely on its hinges, and Susan instinctively looked behind to see the cause of the obstruction. She immediately recognised the appearance of a little parcel, wrapped in a scrap of newspaper, and evidently containing money. She stooped and picked it up. ‘Look!’ said she, sorrowfully, ‘the mother was bringing this for her child last night.’

But Mrs. Leigh did not answer. So near to the ascertaining if it were her lost child or no, she could not be arrested, but pressed onwards with trembling steps and a beating, fluttering heart. She entered the bed-room, dark and still. She took no heed of the little corpse, over which Susan paused, but she went straight to the bed, and withdrawing the curtain, saw Lizzie,—but not the former Lizzie, bright, gay, buoyant, and undimmed. This Lizzie was old before her time; her beauty was gone; deep lines of care, and, alas! of want (or thus the mother imagined) were printed on the cheek, so round, and fair, and smooth, when last she gladdened her mother’s eyes. Even in her sleep she bore the look of woe and despair which was the prevalent expression of her face by day; even in her sleep she had forgotten how to smile. But all these marks of the sin and sorrow she had passed through only made her mother love her the more. She stood looking at her with greedy eyes, which seemed as though no gazing could satisfy their longing; and at last she stooped down and kissed the pale, worn hand that lay outside the bed-clothes. No touch disturbed the sleeper; the mother need not have laid the hand so gently down upon the counterpane. There was no sign of life, save only now and then a deep sob-like sigh. Mrs. Leigh sat down beside the bed, and still holding back the curtain, looked on and on, as if she could never be satisfied.

Susan would fain have stayed by her darling one; but she had many calls upon her time and thoughts, and her will had now, as ever, to be given up to that of others. All seemed to devolve the burden of their cares on her. Her father, ill-humoured from his last night’s intemperance, did not scruple to reproach her with being the cause of little Nanny’s death; and when, after bearing his upbraiding meekly for some time, she could no longer restrain herself, but began to cry, he wounded her even more by his injudicious attempts at comfort; for he said it was as well the child was dead; it was none of theirs, and why should they be troubled with it? Susan wrung her hands at this, and came and stood before her father, and implored him to forbear. Then she had to take all requisite steps for the coroner’s inquest; she had to arrange for the dismissal of her school; she had to summon a little neighbour, and send his willing feet on a message to William Leigh, who, she felt, ought to be informed of his mother’s whereabouts, and of the whole state of affairs. She asked her messenger to tell him to come and speak to her,—that his mother was at her house. She was thankful that her father sauntered out to have a gossip at the nearest coach-stand, and to relate as many of the night’s adventures as he knew; for as yet he was in ignorance of the watcher and the watched, who silently passed away the hours upstairs.

At dinner-time Will came. He looked red, glad, impatient, excited. Susan stood calm and white before him, her soft, loving eyes gazing straight into his.

‘Will,’ said she, in a low, quiet voice, ‘your sister is upstairs.’

‘My sister!’ said he, as if affrighted at the idea, and losing his glad look in one of gloom. Susan saw it, and her heart sank a little, but she went on as calm to all appearance as ever.

‘She was little Nanny’s mother, as perhaps you know. Poor little Nanny was killed last night by a fall downstairs.’ All the calmness was gone; all the suppressed feeling was displayed in spite of every effort. She sat down, and hid her face from him, and cried bitterly. He forgot everything but the wish, the longing to comfort her. He put his arm round her waist, and bent over her. But all he could say, was, ‘Oh, Susan, how can I comfort you? Don’t take on so,—pray don’t!’ He never changed the words, but the tone varied every time he spoke. At last she seemed to regain her power over herself; and she wiped her eyes, and once more looked upon him with her own quiet, earnest, unfearing gaze.

‘Your sister was near the house. She came in on hearing my words to the doctor. She is asleep now, and your mother is watching her. I wanted to tell you all myself. Would you like to see your mother?’

‘No!’ said he. ‘I would rather see none but thee. Mother told me thou knew’st all.’ His eyes were downcast in their shame.

But the holy and pure, did not lower or veil her eyes.

She said, ‘Yes, I know all—all but her sufferings. Think what they must have been!’

He made answer low and stern, ‘She deserved them all; every jot.’

‘In the eye of God, perhaps she does. He is the Judge: we are not.’

‘Oh!’ she said with a sudden burst, ‘Will Leigh! I have thought so well of you; don’t go and make me think you cruel and hard. Goodness is not goodness unless there is mercy and tenderness with it. There is your mother who has been nearly heart-broken, now full of rejoicing over her child—think of your mother.’

‘I do think of her,’ said he. ‘I remember the promise I gave her last night. Thou shouldst give me time. I would do right in time. I never think it o’er in quiet. But I will do what is right and fitting, never fear. Thou hast spoken out very plain to me; and misdoubted me, Susan; I love thee so, that thy words cut me. If I did hang back a bit from making sudden promises, it was because not even for love of thee, would I say what I was not feeling; and at first I could not feel all at once as thou wouldst have me. But I’m not cruel and hard; for if I had been, I should na’ have grieved as I have done.’

He made as if he were going away; and indeed he did feel he would rather think it over in quiet. But Susan, grieved at her incautious words, which had all the appearance of harshness, went a step or two nearer—paused—and then, all over blushes, said in a low, soft whisper—

‘Oh Will! I beg your pardon. I am very sorry—won’t you forgive me?’

She who had always drawn back, and been so reserved, said this in the very softest manner; with eyes now uplifted beseechingly, now dropped to the ground. Her sweet confusion told more than words could do; and Will turned back, all joyous in his certainty of being beloved, and took her in his arms and kissed her.

‘My own Susan!’ he said.

Meanwhile the mother watched her child in the room above.

It was late in the afternoon before she awoke; for the sleeping draught had been very powerful. The instant she awoke, her eyes were fixed on her mother’s face with a gaze as unflinching as if she were fascinated. Mrs. Leigh did not turn away, nor move. For it seemed as if motion would unlock the stony command over herself which, while so perfectly still, she was enabled to preserve. But by-and-bye Lizzie cried out, in a piercing voice of agony—

‘Mother, don’t look at me! I have been so wicked!’ and instantly she hid her face, and grovelled among the bedclothes, and lay like one dead—so motionless was she.

Mrs. Leigh knelt down by the bed, and spoke in the most soothing tones.

‘Lizzie, dear, don’t speak so. I’m thy mother, darling; don’t be afeard of me. I never left off loving thee, Lizzie. I was always a-thinking of thee. Thy father forgave thee afore he died.’ (There was a little start here, but no sound was heard). ‘Lizzie, lass, I’ll do aught for thee; I’ll live for thee; only don’t be afeard of me. Whate’er thou art or hast been, we’ll ne’er speak on’t. We’ll leave th’ oud times behind us, and go back to the Upclose Farm. I but left it to find thee, my lass; and God has led me to thee. Blessed be His name. And God is good too, Lizzie. Thou hast not forgot thy Bible, I’ll be bound, for thou wert always a scholar. I’m no reader, but I learnt off them texts to comfort me a bit, and I’ve said them many a time a day to myself. Lizzie, lass, don’t hide thy head so, it’s thy mother as is speaking to thee. Thy little child clung to me only yesterday; and if it’s gone to be an angel, it will speak to God for thee. Nay, don’t sob a that ‘as; thou shalt have it again in Heaven; I know thou’lt strive to get there, for thy little Nancy’s sake—and listen! I’ll tell thee God’s promises to them that are penitent—only doan’t be afeard.’

Mrs. Leigh folded her hands, and strove to speak very clearly, while she repeated every tender and merciful text she could remember. She could tell from the breathing that her daughter was listening; but she was so dizzy and sick herself when she had ended, that she could not go on speaking. It was all she could do to keep from crying aloud.

At last she heard her daughter’s voice.

‘Where have they taken her to?’ she asked.

‘She is down stairs. So quiet, and peaceful, and happy she looks.’

‘Could she speak! Oh, if God—if I might but have heard her little voice! Mother, I used to dream of it. May I see her once again—Oh mother, if I strive very hard, and God is very merciful, and I go to heaven, I shall not know her—I shall not know my own again—she will shun me as a stranger and cling to Susan Palmer and to you. Oh, woe! Oh, woe!’ She shook with exceeding sorrow.

In her earnestness of speech she had uncovered her face, and tried to read Mrs. Leigh’s thoughts through her looks. And when she saw those aged eyes brimming full of tears, and marked the quivering lips, she threw her arms round the faithful mother’s neck, and wept there as she had done in many a childish sorrow, but with a deeper, a more wretched grief.

Her mother hushed her on her breast; and lulled her as if she were a baby; and she grew still and quiet.

They sat thus for a long, long time. At last Susan Palmer came up with some tea and bread and butter for Mrs. Leigh. She watched the mother feed her sick, unwilling child, with every fond inducement to eat which she could devise; they neither of them took notice of Susan’s presence. That night they lay in each other’s arms; but Susan slept on the ground beside them.

They took the little corpse (the little unconscious sacrifice, whose early calling-home had reclaimed her poor wandering mother,) to the hills, which in her life-time she had never seen. They dared not lay her by the stern grand-father in Milne-Row churchyard, but they bore her to a lone moorland graveyard, where long ago the quakers used to bury their dead. They laid her there on the sunny slope, where the earliest spring-flowers blow.

Will and Susan live at the Upclose Farm. Mrs. Leigh and Lizzie dwell in a cottage so secluded that, until you drop into the very hollow where it is placed, you do not see it. Tom is a schoolmaster in Rochdale, and he and Will help to support their mother. I only know that, if the cottage be hidden in a green hollow of the hills, every sound of sorrow in the whole upland is heard there—every call of suffering or of sickness for help is listened to, by a sad, gentle-looking woman, who rarely smiles (and when she does, her smile is more sad than other people’s tears), but who comes out of her seclusion whenever there is a shadow in any household. Many hearts bless Lizzie Leigh, but she—she prays always and ever for forgiveness—such forgiveness as may enable her to see her child once more. Mrs. Leigh is quiet and happy. Lizzie is to her eyes something precious,—as the lost piece of silver—found once more.3The “lost piece of silver” refers to Luke 15:8, “Either what woman having ten pieces of silver, if she lose one piece, doth not light a candle, and sweep the house, and seek diligently till she find ”it”?” Susan is the bright one who brings sunshine to all. Children grow around her and call her blessed. One is called Nanny. Her, Lizzie often takes to the sunny graveyard in the uplands, and while the little creature gathers the daisies, and makes chains, Lizzie sits by a little grave, and weeps bitterly.

Original Document

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Topics

- Domestic Fiction

- Didactic literature

- Social problem fiction

- Women’s literature

- Working-class literature

- Realist fiction

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell. “Lizzie Leigh, Part 3.” Household Words: A Weekly Journal, vol. 1, no. 3, 1850, pp. 60-5. Edited by Emily Hilton. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 19 April 2024, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/lizzie-leigh-part-3/.

Editors

Emily Hilton

Lesli Mortensen

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

24 October 2016

Last modified

19 April 2024

Notes

| ↑1 | Quote from Luke 15:32. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | An excerpt from Barry Cornwall’s poem, “On the Portrait of a Child,” from The Prose and Poetry of Europe and America: Consisting of Literary Gems and Curiosities, and Containing the Choice and Beautiful Productions of Many of the Most Popular Writers of the Past and Present Age, Ed. G. P. Morris and N. P. Willis, New York: Leavitt & Allen, 1845, 581. |

| ↑3 | The “lost piece of silver” refers to Luke 15:8, “Either what woman having ten pieces of silver, if she lose one piece, doth not light a candle, and sweep the house, and seek diligently till she find ”it”?” |