Helen Fairfax

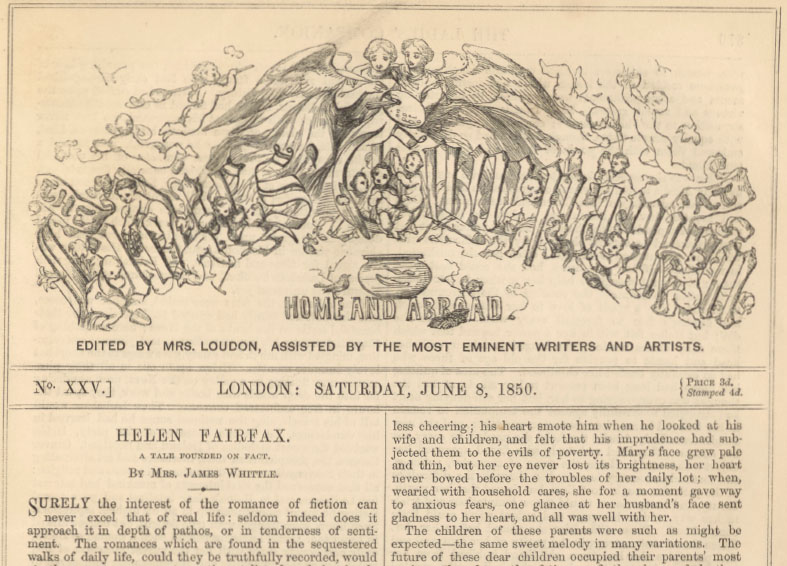

The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad, vol. 1, issue 25 (1850)

Pages 369-371

Introductory Note: Part girls’ adventure fiction, part epistolary narrative, “Helen Fairfax” sets out to depict the “romance” of everyday life. The story recounts the adventures of a governess, a topic made popular by novels such as Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the first of two parts:

Surely the interest of the romance of fiction can never excel that of real life: seldom indeed does it approach it in depth of pathos, or in tenderness of sentiment. The romances which are found in the sequestered walks of daily life, could they be truthfully recorded, would startle many a worn-out sentimentalist, by their simple unaffected portraiture of human sorrow; and the heart, satiated with tales of feigned woe, might respond in its inmost chords to the noble deeds of life’s true heroes.

In a remote village in the north of England dwelt a poor curate, whose slender income had been no hinderance to his marrying in early life. No lessons yet inculcated have taught Love not to nestle in hearts where prudence should forbid its entrance; men will love and women will listen, even though poverty lift its warning finger and tell of hardships to come. Born to no wealth but that which lies buried in the depths of a pure and noble soul, Edmund Fairfax had won honours at college, by his distinguished talents, and life in those youthful days promised a bright career to his ardent spirit; he saw no limits to his success, as he felt none to his aspirations; all seemed to lie within the grasp of his intellect, and he had yet to learn that “the race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong.” The Church had been the profession of his early choice, and he vainly believed that the earnest spirit in which he regarded the duties of his holy office, and the zeal with which he devoted himself to their discharge, would ensure him a position, and satisfy the moderate ambition of his nature. He had been the favourite of his tutor at Cambridge, by whose influence he was early appointed to a curacy in Westmoreland, and his speedy good fortune tended to increase his security of ultimate success. By this appointment he felt himself justified in asking her whom he loved from his boyhood to share his humble home. Mary Horsmann was not deaf to his voice: their attachment had sprung up at that season when the heart asks no questions of the future,—the present suffices it, to love and to be loved seems all that the wisest can desire; she heard his proposal with a thrill of happiness, and placing her hand in his, said, “I am yours, Edmund, as I have ever been; I cannot recal the hour when I did not love you; life will be happiness when shared with you; let joy or sorrow come, all will be welcome while you are by my side.” Were these mere words? Time proved them truths. Care and trouble came, and sorrow too; children grew up around them, and the income that had sufficed for the wants of this simple loving couple failed to supply comforts to the increasing circle. Edmund found his hopes of preferment decline; forgotten by those who had admired and flattered his talents, his prospects grew daily less and less cheering; his heart smote him when he looked at his wife and children, and felt that his imprudence had subjected them to the evils of poverty. Mary’s face grew pale and thin, but her eye never lost its brightness, her heart never bowed before the troubles of her daily lot; when, wearied with household cares, she for a moment gave way to anxious fears, one glance at her husband’s face sent gladness to her heart, and all was well with her.

The children of these parents were such as might be expected—the same sweet melody in many variations. The future of these dear children occupied their parents’ most anxious thoughts; the fatigues of the day ended, they would sit over the dying embers of their fire, meditating on the means within their power of helping their sons and daughters to establish themselves respectably in the world, and often did their hearts sink at the cheerless prospect before them; yet did their faith in God never desert them, in their darkest moments they faltered not. “He who careth for the sparrows, who numbereth the hairs of our head, will not forsake these little ones. His will be done.”1I.e. Jesus Christ; a reference to Luke 12:7. Thus comforting each other, they retired to rest in peace and sleep.

The heroine of our tale is one of this simple and delightful family. Helen was the eldest of six children, the brightest flower that bloomed in that sweet Eden, the pride and darling of the neighbourhood—of rare loveliness: a pure soul, a warm heart, and a clear intellect gave a stamp of rare beauty to her features, and cold would have been the heart that denied the homage of admiration and love to Helen Fairfax. Is it a good or an evil spirit that waits on the birth of such rare beings, dooming them to troubles, to sorrows, to conquests, that more earthly natures dream not of? Were earth our final resting-place, we might name the spirit that subjects such natures to suffering evil: but earth is not our all; there is a better world beyond, and to that world we can alone aspire through patient endurance of present trials.

Edmund Fairfax’s parish was situated in the most beautiful part of Westmoreland, and was the resort of travellers drawn thither by the beauty of the lake-scenery in the vicinity.2Westmoreland, an area (and historically a county) in northwestern England, is part of the Lake District, known for its picturesque mountains and lakes. As the home of literary figures such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the region was also known for its connections with literary masters. Some families, tempted not only by the charms of nature but by the promise of society in the neighbourhood, fixed their residence near W. . . . . during the winter. Edmund Fairfax was sought by all; his profession rendered him a welcome guest in every family, and his individual character won the respect and love of every one; nor were his wife and family scarcely less valued, for rarely are such companions as Westmere Parsonage afforded found in scenes so secluded and remote. Amongst these strangers was one family who remained from year to year;—with health and station to have made the gay world their natural sphere, they preferred their lonely cottage by Windermere to the allurements of a London life;—surrounded by their children, with a fine library at their command, neither Lady Ainslie nor her husband needed more: three beautiful girls were the objects of their unwearied love and care; and all the advantages that affection, guided by good sense and judgment, could secure, with wealth to aid, were lavished on these daughters. A governess resided in the house, whose rare mental endowments and accomplishments were equalled by her sterling virtues and moral graces. Such friends were a priceless acquisition to the Fairfax family; congenial in pursuits, and with equally simple tastes, though fortune had so differently endowed them with the goods of this world, they became true friends.

Helen was the especial favourite of all, and she was invited by Lady Ainslie to join her young companions in their studies, and to take advantage of Mrs. Charmion’s instructions. Days and months flew on; Helen was a child no longer; her nature had expanded to full beauty; her gay young spirit had been awakened to earnest thought, by the difficulties with which her parents had to struggle; often had she meditated, in the silence of her own heart, how she could best assist them; it was not enough to help her mother in her household duties, to promote the comfort of those around her, to minister like a spirit of love to her father, and watch her mother’s face to forestall every wish. All this she did; but Helen felt within her a power beyond that which these daily duties needed; she longed to labour with her head and hands to provide for the old age of those who had so carefully tended her childhood. The idea of quitting her home had long been present to her mind; at first the thought was overpowering to her, but her self-denying heart had struggled successfully against the temptation to remain in her beloved home; her resolution was taken, and she now sought from Lady Ainslie the help she needed to carry out her design. This kind and truly wise friend approved her object; she saw in Helen the force of character, patience, and fortitude necessary to carry her through the difficulties of the path she sought to follow, but feared that her youth, beauty, and inexperience would throw temptations and trials in her way, which her pure and ardent spirit could little comprehend. These difficulties she placed before her, but Helen feared not; strong in the purity of her own soul and the principles she had from childhood imbibed from her parents’ lips, she steadily, and somewhat indignantly, resisted the reasoning of her friend, and persisted in her desire to become a governess, in the hope of providing for her parents. Helen’s wish was to travel; foreign scenes had a powerful attraction for her lively imagination, and when Lady Ainslie told her that a friend of hers, married to a Russian nobleman, was then in England, and desirous of finding an English governess willing to return with her to Russia, Helen’s heart beat high with hope, that she might, through Lady Ainslie’s influence, obtain the situation. When the moment came for her to communicate her resolution to her parents, Helen’s courage was severely tried; the proposal was received with dismay, and met with determined opposition from her family, but it was strongly supported by Lady Ainslie, and, touched by the noble motives of her conduct, her parents at length yielded to her eloquent appeal, and withdrew their prohibition to the plan. The situation was obtained through Lady Ainslie’s warm recommendation, and Helen quitted her beloved home for ever.

In the Princess Soltikoff, Helen found a kind and maternal friend, and when time had softened the first grief of separation from her home there was much in her new life to charm and interest her. She was treated like an elder daughter by the Princess, and her pupils were fine promising creatures, who well repaid her care: Helen found a peace and happiness in her present occupation, which those only enjoy, who earn them by patient self-denial. From her ample salary she sent to her parents sums of money which assisted them in the education of their sons and daughters; through her means anxiety and poverty were banished from Westmere. Her highest wishes were attained; her act of self-sacrifice had brought an abundant harvest, and though she sometimes longed to see once more the happy home she thus gladdened by her exertions, yet she knew how much they were still required, and how necessary she herself was to the family with whom she lived: to these friends she was bound by many ties of gratitude and affection, and she felt every year more difficulty in breaking the gentle bonds that detained her in Russia.

The family of Prince Soltikoff consisted of two daughters and a son; the latter was older than his sisters by several years, and had been travelling with his tutor since Helen had been a resident in the family; his return was now anticipated with great joy by all. Ladislaus was the darling of his parents, beloved by all who knew him, the promising heir of an ancient and noble family who had early distinguished themselves in Russian history. Fortune had smiled upon the youthful Ladislaus, his life had flowed in one smooth uninterrupted course; with wealth at his command, he had never forgotten the claims of those beneath him; generous, kind, considerate, he was as good as he was great, and formed a bright exception to the general character of his youthful countrymen. Travel had enriched a naturally fine intellect, and, far in advance of his country’s age, Ladislaus stood alone in all that dignifies a man. Well might his mother’s heart beat high with joy as she once more clasped him to her bosom! Well might his father’s cheek flush with proud delight as he gazed upon his manly form, and read high chivalric virtues in his noble countenance. His return was the signal for fêtes and festivals. St. Petersburg rang with praises of Ladislaus Soltikoff, and Helen shared with reflected pleasure the universal joy.

Time rolled on, the fêtes were ended, summer was come, and the Soltikoff family had quitted St. Petersburg for their beautiful castle on the banks of the Neva; here something of English domestic life was to be found, and pleasant conversation, mingled with mirth and gaiety, gave wings to the short but lovely summer months. Helen made one in all their pleasures; now floating in a galley on the Neva, now wandering far into the deep woods with books and work, they spent the hours in free unfettered converse. Then Ladislaus would tell of his travels, sing the national songs he had learned in his wanderings, or, at the entreaty of the party, Helen warbled the sweet melodies of Ireland and Scotland. Graver themes, too, occupied their time, literature and art alternating in their conversations with discussions on morals and religion: all that concerned the vital interests of mankind had interest for Ladislaus, and in Helen’s clear intellect and pure moral feeling he found companionship in all his highest aspirations. Such hours were fraught with true delight, but danger lurked in them too. Could Ladislaus behold such a woman as Helen, daily and hourly share with her the purest pleasures of life, watch her as she gracefully and unconsciously ministered to the happiness of all around her—could he see her and not love? Such was not his nature; woman had as yet attracted his fancy only, he had admired and dreamed he loved, but never before had he recognised woman’s power, never trembled as he felt that life could have no charm unless shared with the one he loved. He knew the spell was on him now—he lived but in Helen’s presence; the world seemed brighter, the sun shed a more glorious effulgence, the moon a softer radiance, when she was by his side: he loved, and gloried in his love.

But Helen—what did she feel? For many months she had closed her eyes in fear; she trembled when she felt his eye fixed upon her: she dared not question her own heart; all there was chaos: she knew that she could never be his wife, and perhaps the strength of this conviction had lulled asleep the dragon prudence. Be it as it may, the party had wandered from them, and they were alone with nature in one of those dark magnificent forests which civilised lands possess not, Ladislaus, taking her hand, said,—“Let us rest here, Helen; here let me learn my fate; I can no longer live near you and keep the secret of my heart; tell me, has earth still hope for me? Helen, that earth is a desert without your love.”

Poor Helen, faint and sick with overwhelming emotion, buried her face in her hands, and for a few moments remained silent; but as the habit of indulging no feeling unsanctioned by duty had by long practice become second nature to her, she raised her head, and with a scarcely trembling voice answered,—“Do not tempt me to forget my duty; I cannot, dare not listen to you. Leave me, I implore you; for your sake, for mine, banish this feeling from your mind.”

“Oh, Helen! can you indeed believe it possible I should obey you—are feelings like mine thus easily to be uprooted and destroyed? Hear me, Helen; I have well considered the step I am taking: wealth, rank, what are they compared to the riches and nobility of the soul?—these you possess, and what have I to offer in return?” At these words Helen involuntarily raised her eyes to his. It was for a moment, but in that glance a new world seemed revealed to them both. Bursting into tears she hastily turned away, and walked rapidly towards the house, signing to him not to follow her. Ladislaus remained rooted to the spot. Alone in her room, Helen sank on the floor; long did she strive, in agony of soul, to still the throbbing of her heart; at length, raising herself, she said,—“I dare not, must not, see him again; another flame from those eyes and all my strength would vanish. Great God, is thy child indeed so weak that she must fall before her first temptation. Forsake me not! in this dread hour be near me; and, Father! ‘speak peace to him.’” She rose calm and strengthened; her resolution was taken, and unfalteringly did this noble girl pursue the path she then marked out for herself: she steadily fulfilled her daily duties, entreating permission to live for a time in the retirement of her own apartments, pleading as a cause the necessity of study, in order to keep pace with her pupils’ rapid progress. Courageously adhering to her resolution, she resisted every effort made by the Princess and her daughters to induce her to join the family circle; the entreaties of her pupils were as earnest as they were vain. Perhaps their mother saw the struggle, for she soon ceased to urge her wishes, while her love and care for Helen seemed to redouble. All that could enliven and cheer her solitude was placed in silence within her reach, and a spirit of gentle loving-kindness surrounded her steps. Every attempt made by her lover to see her was firmly resisted; she would receive no letters, and maintained the strictest seclusion, lest chance should bring about a meeting. Weeks dragged heavily along, and Helen, with fear and dread, asked her own heart how it would end.

(‘To be continued.’)

Word Count: 3066

This story is continued in Helen Fairfax, continued.

Original Document

Topics

- Adventure fiction

- Girls’ fiction

- Love story/Marriage plot

- Women’s literature

- Governess Story

- Domestic Fiction

- Realist fiction

- Poland

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Catharine Taylor Whittle. “Helen Fairfax.” The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad, vol. 1, no. 25, 1850, pp. 369-71. Edited by Emeline Gardner. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 3 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/helen-fairfax/.

Editors

Emeline Gardner

Claire Nielsen

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

14 October 2016

Last modified

3 March 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | I.e. Jesus Christ; a reference to Luke 12:7. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Westmoreland, an area (and historically a county) in northwestern England, is part of the Lake District, known for its picturesque mountains and lakes. As the home of literary figures such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the region was also known for its connections with literary masters. |