Whirlwind Reapers

A 1 Annual, vol. 1, issue 1 (1888)

Pages 7-10

Introductory Note: “Whirlwind Reapers” explores the moral dimensions of gambling. As a didactic tale, it includes a remarkably insightful depiction of what we would now term gambling addiction. Along the way, it also addresses cruelty to animals, citing specifically the work of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Advisory: This story contains an ableist slur.

“HERE we are at last! I never thought it would come true, did you, Erminie?”

“I hoped it would not, Gertrude.”

“Ah! I forgot. In the rush and bustle of preparation, your special aversion to this particular mode of passing our time was lost sight of. “I believe we are quite near the course,” said Gertrude, crossing over to the window. “Yes we are ; that is a delightful fact. We shall see a lot of the fun that others cannot.”

“How so?”

“Why, Phil says the horses are exercised in the morning, which is a pretty sight, to say nothing of its being such an advantage.”

“No advantage to us,” said Erminie, looking over her sister’s shoulder.

“Indeed it will, my dear ; for if ‘Loadstone’ wins, it will put thirty pounds into my poor pocket. And by the same rule, if ‘Sunflower’ goes in first, I shall have to hand that amount to Phil. The advantage of being here is, that we shall get a better idea of which horse is likely to be the winner ; and up to the last, there is the chance of so arranging the bets as not to lose.”

“I am surprised at you and Phil,” sighed Erminie ; “and I do not think you ought to encourage him in betting. You cannot wonder at men, if women do the same thing.”

“It is the greatest fun, I can assure you, Ermie ; and I do believe it to be a crime of deeper dye to speculate upon the merits of the horses, than it is to witness the race. Why did you come, if you consider it all so very wicked?”

“You know, Gertie, papa would have been angry if I had refused ; and if not, I could neither have stayed at home alone, nor invited myself out for the week—and there is quite enough to pay for this house.”

“Do you know how much, Erminie?”

“Three hundred and fifty pounds.”

“Is it as much as that? But what can it matter if papa wins as many thousands?”

These sisters were the handsome and highly educated daughters of Tudor Lawson, who had recently become head of an old established city firm. Many years before he had come to the Metropolis, fresh from the country, where, brought up by a pure-hearted and gentle mother, and a hard-working Christian father, he had known nothing but the simple pursuits of a country life.

Distant relationship claimed for him an interest in the firm of “Lawson and Pierpont,” accountants, and when barely seventeen, he found himself in the important position of chief clerk to the manager.

At the village school, Tudor had always been distinguished for his arithmetical powers, which here developed with a rapidity that astonished his superiors, and won for him the golden opinion of all with whom he was associated in business. The family connection that had brought him to London, also introduced him to the family circle of the Pierponts, and but a few years passed before the distant relationship was exchanged for a nearer one, by the marriage of Tudor Lawson with Gertrude Pierpont.1For “connection” the original reads “conexion.”

As a child, Tudor had been taught to pray at his mother’s knees, and through all the somewhat uneventful years of his early life, he had preserved not only the outward form of religion, but his every-day actions had been so influenced by the power of parental example, and by his personal acquiescence in the principles of Divine truth, that he carried with him into his London work, unswerving moral rectitude, which continued to flourish for several years after his transplanting into a rougher soil. But like thousands of others, who have shown fair promise of bearing spiritual fruit in the years of prime and old age, he, too, had but reached the tender age of twenty-one, when the first little withered leaf appeared that threatened the total decay of all spiritual life.

The Pierponts were a professedly worldly family, making no pretence even to the decorous custom of a regular attendance at church.

At first, these frivolous manners caused considerable uneasiness of mind to one who had been for so long the recipient of gentler influences. But the foundation on which he had set his feet, soon proved insufficient to resist the overwhelming flood of opposition that he met whenever he attempted to carry out his own convictions, and although, as a boy, much of the Word was registered on his brain, it was now but too evident that it had never been hidden in his heart. His religion was a mere custom that died out as easily as any other, and Tudor Lawson and his wife launched themselves upon the sea of married life, entirely ignoring the Divine hand that was stretched out to guide them in safety to the heavenly harbour.

It was in the Pierponts’ house that Tudor Lawson had learned to gamble. At first, shocked at his own gains, and unable to devote the money won to any but charitable purposes, he shortly found the winning of them so exciting, and the possession of them so sweet, that the wholesome dread of such questionable modes of obtaining money which had grown up with him faded out of his memory, and by the time the new house at Kensington was furnished, a billiard-room had become a necessity.

From billiards and card playing, Tudor easily slipped a step further. The solicitations of some of his chosen friends lured him to the betting field. It was with a decided shudder that he took his first step in this unrighteous profession, as words of warning, spoken by his parents before he left the home of his childhood, returned to his recollection and rang in his ears. But the excitement of success in his very first venture swept away the last cobwebs of remorse that clung to his mind, and from that time, through all the years of his partnership in the firm, he indulged his passion to the full. His ventures were not all successful, and the drain upon his income was bound in time to make itself felt, until every year found him recording a still more serious deficiency.

Anxiety for the future awoke, and he with difficulty kept matters from his family. Just as he was anticipating an unpleasant disclosure of his affairs, however, Mr. Pierpont intimated his intention of retiring from business, and not a week too soon were the necessary arrangements made that rescued his son-in-law from the disgrace of bankruptcy, and put into his hand the entire management of the flourishing concern, which had seen the retirement of several partners, to whom, however, the betting fever had been a disease unknown. The ample means thus placed at his disposal cleared off his numerous debts, and enabled him to make fresh ventures upon his favourite sport.

“A run of luck” so elated him, that, contrary to his usual custom, he took a house for the week of a famous race—a luxury his wife had craved for a long time.

On the morning of the race day, the brother and sister stood together in one of the bay windows of the drawing-room, Gertrude lamenting that the days had fled so swiftly, and Erminie looking forward with deepest satisfaction to the moment when she should turn her back upon the spot.

“I would rather never see the glorious pines again, nor breathe their health-giving odours,” she exclaimed, “and I would be content to stay always in the dull, brick-built streets of London, could I escape participation in so distasteful a diversion.”

“I should not trouble your brick-built city much,” said Philip, “if I could have my choice ; but we business men have to endure a far more continual incarceration than you girls, and you cannot enter into our appreciation of the pine-woods or anything else.”

“Of which I fear the ‘anything else’ takes by far the larger amount of interest,” she answered. “Say, is it not so?”

“Maybe,” replied her brother, “inasmuch as I would, if I could, be at a race every day of my life. I am contemplating arranging a complete list of them all, and making the experiment of going the round during the next year, provided, of course, that my valuable services at the office can be dispensed with for the time. It is sweeter to win even thirty pounds than gaze upon a thousand pines.”

“Which you will not win to-day,” laughed Gertrude, “for I was up before you this morning, and I can tell you that ‘Loadstone’ was never in better form at his practice ; he made a little ruse of lagging once or twice, but when occasion really required it, he shot ahead easily, and came in all right.”

“Poor beast!” said Erminie, “I feel quite sure he is not up to the mark in his condition, however ‘easily’ he may have appeared to reach the mark on the course. He is a splendid creature, but his distended nostrils and quivering body told of distress and pain.”

“He will be all right by the time he is wanted,” replied Gertrude.

“Do not get soft and spoil our fun at the last,” said Philip.

“It may be fun to you, Philip,” answered Erminie, “but it is anything but that to the horses. I came across a case in point only yesterday, which I am not likely to forget. Mamma and I had to go into the village, and sent for a fly. They were all out but one, and that was drawn by the most miserable specimen of a horse you could well imagine.”

“A venerable cart-horse, was he?” asked Philip, amused at his sister’s description.

“No, indeed! Perhaps he was once as handsome as ‘Sunflower.’ I wondered why the creature put his head about so much, keeping it pretty well to one side. While mamma went into a shop, I inquired the cause of the driver. He told me the horse had once been a racer, and won a prize ; but in the last race he ran, the strain was so great that he lost his sight. Think of that, Philip. Imagine being forced to exert yourself so much, that the nerves of your eyes were broken by it.”

“Oh, Erminie, do not talk of such disagreeable things!” exclaimed Gertrude, with a disgusted look upon her face. “I am sure the man could not have spoken the truth. And you need not take away our pleasure, if you have none yourself in the races.”

“Pleasure is not a word to be used in connection with such a sport, Gertrude. It is a wicked dissipation to put money into bad men’s pockets. I wish the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals would do something in the matter.”

“What could they do?” asked Philip. “They tried it on a week or two ago, but it was no business of theirs, and the man got off ; of course he had a right to do as he liked with his own animal, and I presume that he knew what he was about.”

“Yes indeed,” replied Erminie indignantly ; “he must have known well enough that he was digging those cruel instruments of torture into the poor brute’s sides, until there were over twenty wounds from which the blood was pouring. He was stated to be a gentleman ; but if good birth and first-class education—so-called—can produce nothing better than a dandified demon with spurs on his heels, I would rather have a friendship of a costermonger who was kind to his donkey.”

“Pray do not excite yourself too much,” said Philip. “It is a practice one detests. I should despise myself if I should put on spurs ; but it is the fashion to wear them at races, and cannot be helped, I suppose.”

“It ought to be helped, or at least should not be supported by people who know better. Many another vicious practice is perpetuated in the same way, I fear.”

* * * *

The grand stand was filled to its remotest corner, its occupants presenting such groups and patches of brilliant colouring, that from a distance it might have been taken for a piece of patchwork. The usual members of the royal family honoured the race with their presence, and needed no external adornment to add to the interest of their appearance.

As the moments flew by, the excitement became intense, and the occupiers of exalted positions were in a flutter of anticipation, while the people below composed a struggling mass of humanity, fighting for the best places, bargaining, betting, shouting, swearing, drinking and smoking.

The critical moment for starting came at length, and the hush of intense interest fell upon the crowds, as they pressed together more closely to get a view of the horses.

Erminie saw in every one as they flew forward, a prospective repetition of the melancholy brute which had drawn her to the village the previous day. Philip and Gertrude gazed with keenest excitement, occasional utterances of hope or fear as to the result of the race breaking from their lips. Presently, however, to the astonishment of many, the scene altogether changed. “Loadstone” fell lame, and in spite of the infuriated attempts of his rider to urge him to the goal, he gradually dropped behind with a painful limp. “Sunflower” also disappointed the myriad watchers of his progress. With all the slashing and spurring that hands and feet could administer, he, too, flagged, and a colt, almost unknown to the public, but familiar to a certain “ring,” went in at an easy canter and won the cup.

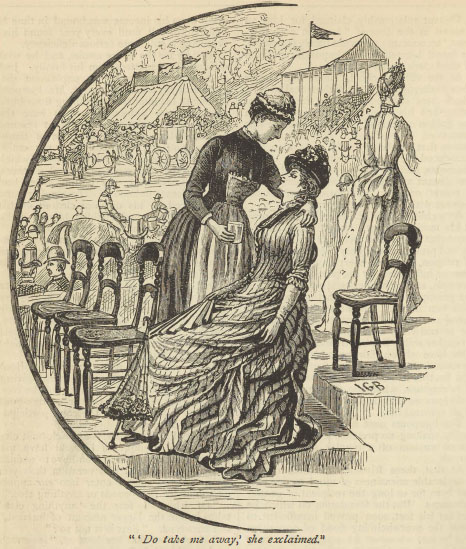

In the general scuffle that commenced the moment the race was over, the wild cheering of those whose favourite had won was scarcely noticed, while the looks of despair and desperation, visible on hundreds of faces, were observed only by a few. The royal party retired, and many other occupants of the grand stand made their escape as speedily as possible from the scene of their sudden dismay. Group after group passed off, but still the Lawsons remained. In their anxious concentration of mind upon the race, they had not noticed that Erminie had fainted. It was some time before they were successful in restoring animation. When at last she opened her eyes, and became conscious of her surroundings, a shudder passed over her ; and presently, rousing herself from the arms of a maid who had been summoned from the refreshment bar to support her, she exclaimed, “Do take me away ; I can bear to stay here no longer. Never again will I be tempted to witness an abomination like this.”

“What can you mean by such language, Erminie?” said Mrs. Lawson, who had been anxiously bending over the prostrate form of her daughter. “You were not compelled to come, but as you are here, you need not surely use words that decidedly imply a want of propriety in the presence of the other members of the family.”

“Mamma, I do not believe it possible that you or Gertrude would ever attend a race, if you knew as much as I do about the cruelty of it.”

“Nonsense, child, the horses are trained by love, and there is nothing improper in attending the races. Do you suppose so many members of the royal family and nobility would sanction them by their presence, if there was anything wrong or cruel connected with them?”

“I do not care who they are that sanction the races by their presence ; I know they are shameful sports, and if the horses are ‘trained by love,’ they are driven to death. Look at that.”

“Look at what?” asked her mother, disdainfully turning her eyes towards the spot indicated. “I do not see anything.”

“I saw it come,” continued Erminie ; “it was slashed off the flank of that elegant creature ‘Sunflower;’ it fell upon a lady’s dress close by you. I always knew it was a wicked amusement, although I thought until lately that the betting was the worse part of it.”

“You might have been mistaken,” said Gertrude ; “perhaps it was only a piece of turf.”

“That is easily proved, Gertie ; the use of your eyes will decide the matter in an instant.”

“I am sure if I thought you were right, I would never patronise a race again,” replied Gertrude, as she stepped over to inspect the object pointed out by her sister. “It is but too sadly true,” she continued, as she returned, with difficulty steadying her steps, for the sight had produced a feeling of disgust and horror ; and as Mrs. Lawson looked at her suddenly pallid face, she feared a second invalid.

“Really now, Gertrude, I hope you are not going to be ridiculous ; one at a time is quite enough. And as to the races, they are not likely to be abolished because they are distasteful to a couple of sentimental girls. They are extremely fashionable sports, and, so long as they exist, fashionable people must patronise them ; if they cannot, they would be better out of the world.”

Only a few weeks after this, Philip spent the best part of the night in pacing wildly across the moorland, after a vain effort to square his accounts. He was fast becoming so entangled in various directions, that he had resolved on asking his father for a still heavier advance than he had ever done before. Aroused in the morning from the deep sleep into which he had fallen, he awoke to the fact that his father stood by his side. He quickly collected his wits to aid him, and was about to spring out and begin dressing, little dreaming of the purpose that had prompted the early visit ; but Mr. Lawson laid a hand upon his shoulder, as he said,—

“Philip, I do not want to disturb you, as it is yet very early, but I want you to give me your closest attention. I want you also to make me a solemn promise, that you will do all in your power to help your mother and sisters when I am gone. Do you comprehend?”

“I do not know that I do quite. Gone, did you say? but you are not ill, father.”

“No, no. I am well enough in health, Philip. I have been on the wrong road for many years. And what is worse, my boy, my bad example has drawn you into it as well. The terrible losses I have had from time to time should have sufficed to warn me from the pursuit of a course which, even as a child, I knew to be a vicious and deceptive one. Had I but followed the good example and advice of my dear parents, I should not now have to fly from home and country.”

“Fly from home and country?” exclaimed Philip, springing up again.

“Listen! listen!” continued Mr. Lawson. “Only be quiet, and it may be well in the future. I am resolved to give you all a chance, but I fear nothing could be done if I stayed here. I have been so much in the hands of others for years, that I could not possibly escape from their association. Elsewhere, perhaps, I may honourably work as in the days of my youth ; and it will be your duty to stand by your mother in every emergency that may transpire. I lay this upon you.”

“Upon me? Why, I am bankrupt myself. I was coming to you to-day for a little cash to set me afloat, until I could get my affairs a bit straight.”

“I hope you are not very deeply in, Philip.”

“Not so deeply as I had been. But if I were, Chaffington races are on next week, and I am pretty sure the tide will turn in my favour. I was a fool to trust Hadley so much. I have made use of my own judgment this time, and intend doing so in the future.”

“Philip, your own judgment is no better than Hadley’s.”

“Perhaps not, father, but at all events I should not cheat myself.”

“I am not so sure of that. I have been cheating myself for many a long year.”

Philip did not answer at first, but his father noted a grave look upon his face. He said at length, “I must say it seems rather hard lines for you to bring us all up to go to the races, and bet on the horses, and then go and leave us in the lurch like this ; and I cannot see the use of it either. I think you should stay and help us out of the difficulty. I wish I had taken Erminie’s advice ; she always hated the races, and it is enough to make anybody hate them to find one’s self in such a dilemma.”

“The ‘lines’ are far harder for me than the rest, Philip, because I know that our life might have been so different, if I had abstained from the sinful pursuits which have wrought this ruin. My deepest regret at this moment is, that I cannot immediately remove my family from the evil influences by which they are surrounded—especially yourself.”

“You have not said where you think of going ; I suppose that is a secret you could not trust even me with. But do you think you will be free from evil influences in any country—Australia, for instance, or America?”

“Going among strangers, my experience would be a safeguard,” replied Mr. Lawson.

“I wish I could go, too,” continued Philip, burying his face in the pillow to hide the emotion he could not check. “You do not know how I am worried. I should never have betted half so much but for the other fellows,—one cannot afford to be different from the rest.”

“Have you any idea of your liabilities, Philip?”

“Yes ; I think I am not very wide of the mark when I say two thousand pounds.”

“That is a great relief to me,” said his father ; “I feared it might be double the amount. If I were sure of only one member of my family standing by me, I would even now face the coming storm ; but it seemed better for all parties that I should go away,—indeed, it appeared the only thing to be done.”

Philip was silent, but presently, raising his head, he said, “I can assure you I am heartily tired of my life. If you think it would be of any use for me to promise to stand by you, I am sure I would.”

“It will be a terrible crash, Philip ; in all probability we shall have scarcely a hundred pounds to begin life again with. Are you prepared to be poor, and perhaps take a clerkship in somebody else’s office?”

“It is not a pleasant look-out, I must confess, dad ; but it would be no worse for me than for you.”

A gleam of hope shone into the father’s sad heart at these words. Who could say but the time might come, when not only himself, but Philip and the rest of the family, should be brought under the power of Divine love, and, with one mind, serve the Lord as they had served Satan?

The “crash” did come, and that shortly, but it found father and son shoulder to shoulder, doing battle with the flood of consequences that followed their folly. Everything was honourably surrendered to meet the requirements of their many creditors, and when all was settled, it was discovered that not even the hoped-for hundred pounds remained to give them a fresh start in business.

The false friends who had clustered about them in the time of their worldly prosperity, happily now gave them a wide berth, since they had nothing now, either for entertainment or speculation, and they were left in peace to plod the daily path they had too thankfully accepted, as subordinates in other men’s offices.

When the truth burst upon Mrs. Lawson, her indignation knew no bounds ; and although it was at her own father’s house that Tudor Lawson first set his feet upon the slippery plane that had landed him in bankruptcy and ruin, she reproached him bitterly, and gathering together all she could secure of her personal property, betook herself to the more congenial society of her parents’ home. Mrs. Lawson would have preferred that Gertrude should accompany her, partly, perhaps, as a palliation of her own heartless conduct ; but her persuasions fell short of the mark, inasmuch as both sisters had resolved to stand by the fallen fortunes of the house.

In a small cottage in a London suburb, these four dwell together, father and son travelling to and from the Metropolis by a cheap train, while Erminie and Gertrude do the work of the house, and prepare the meals with their own hands ; and as father and son now rejoice together that their prosperity is not built upon, nor in any measure augmented by anybody else’s losses or ruin, so the sisters thankfully realise the fact that their presence at the races will never again give countenance or encouragement to the various frauds and impostures, upon which alone the professional gamblers of all sorts and conditions feed and fatten.

Word Count: 4430

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Mrs. John Brett. “Whirlwind Reapers.” A 1 Annual, vol. 1, no. 1, 1888, pp. 7-10. Edited by Krista Isom. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 9 February 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/whirlwind-reapers/.

Editors

Krista Isom

Nicole Clawson

Lesli Mortensen

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

14 January 2017

Last modified

9 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | For “connection” the original reads “conexion.” |

|---|