The Wishing-Book: A Stray Glimpse of the Wonderful in Modern Life

Heath’s Book of Beauty, vol. 10 (1842)

Pages 11-43

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Wishing-Book” is a frame story, a love story, and a story of gothic mysticism all in one. It’s an entertaining tale that includes a subtle critique of the poor treatment of women. The narrator relates a strange story about his lost love to his young ward, Clara. It’s only as the story unfolds that Clara learns how the Wishing-Book impacted her past.

Advisory: This story contains ableist slurs and descriptions.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the first of two parts:

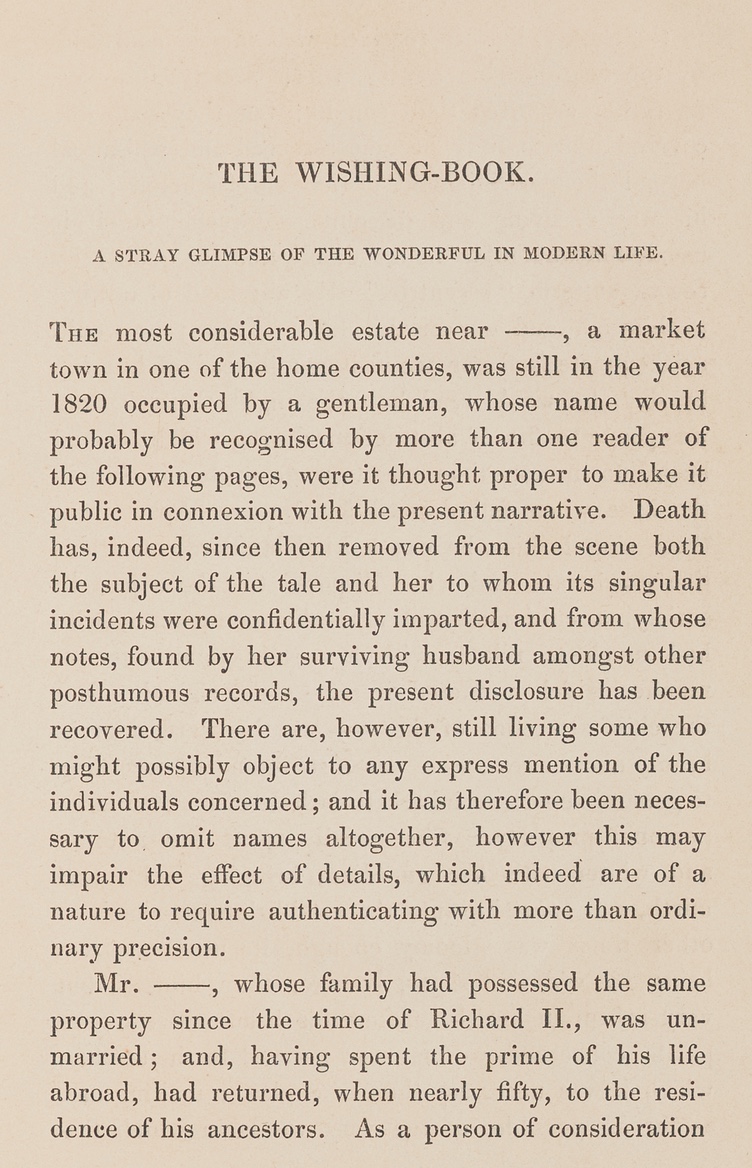

The most considerable estate near ––––—, a market town in one of the home counties, was still in the year 1820 occupied by a gentleman, whose name would probably be recognised by more than one reader of the following pages, were it thought proper to make it public in connexion with the present narrative. Death has, indeed, since then removed from the scene both the subject of the tale and her to whom its singular incidents were confidentially imparted, and from whose notes, found by her surviving husband amongst other posthumous records, the present disclosure has been recovered. There are, however, still living some who might possibly object to any express mention of the individuals concerned; and it has therefore been necessary to omit names altogether, however this may impair the effect of details, which indeed are of a nature to require authenticating with more than ordinary precision.

Mr. ––––, whose family had possessed the same property since the time of Richard II. , was un-married; and, having spent the prime of his life abroad, had returned, when nearly fifty, to the residence of his ancestors. As a person of consideration in the county, he was received with various courtesies by the neighbouring gentry, whose society, however, he rather admitted than sought: but they soon discovered him to have become reserved and whimsical beyond the general habit of rich old bachelors; and his way of living and discourse were such as it is usual, for want of a better description, to qualify by the vague term “eccentric.” He was fond of talking to himself, and on certain days of the year would neither taste food nor see visitors; instead of hunting by day, he would read half the night through, and was prone to fits of abstraction, during which he had been known more than once to wade up to his chin in the lake when full dressed for dinner. Apart from these singularities, he was a kind landlord, an attentive magistrate, and when disposed to take a part in society, a cultivated and agreeable companion, who had much to relate, with a certain quaintness of manner which rendered it racy and original. But the chief attraction of the –––– was his ward, a great beauty and heiress, who was also intended, according to general report, to inherit the whole of his own large personal property. She usually spent the autumn and winter with her guardian, bringing light, and mirth, and courtship into the establishment, which at other times was gloomy enough, its usual mistress being his widowed sister, younger than himself, but very infirm in health. After this brief notice of the parties concerned, we may now proceed to the extract, which it was necessary thus to explain; making use, as far as possible, of the very words in which this young lady, Mr. ––––’s ward, set down, at the time, a conversation, concerning which many questions may arise, which now there are no longer any means of answering.

A few days after her arrival at the ––––, in the September of 1816, Mr. –––– was sitting in the twilight with his ward before an open window in the library, the day having been sultry. He had been playfully questioning her upon her conquests during the last season, and receiving such replies as young ladies of three-and-twenty usually return to such inquiries; by degrees his manner became more serious, and he ended by plainly and gravely expressing his wish that she might soon find, if she had not already found, one whom she could worthily and heartily love. The fluttered way in which Clara received the admonition might have justified a suspicion that half of the wish at least had been already fulfilled, but the deepening twilight concealed her emotion; she only looked aside for a moment, and then answered, half laughing, half singing, with an imitation of Leporello’s well-known air,—

“No, non voglio mai servir! At least, not yet. Not until I have found what will really repay the loss of that precious thing—a free heart.”1“No, non voglio mai servir” is Italian for “No, I will never serve.” Clara is alluding to Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787), in which the servant Leporello longs to be a gentleman and “non voglio più servir,” serve no longer.

“My little Clara,” he replied, “the heart, especially woman’s, was never designed to be free.”

“That is one of the tyrannous maxims invented for the benefit of the stronger sex. Pray Heaven that the application may not be the proposal of some unexceptionable mariage de raison!”2A “mariage de raison” is a marriage of convenience, rather than of love.

“Not from me,” was the answer: “on such a point I have no faith in reason alone; but if it meet with inclination—”

“Which it may,” interrupted Clara,

“‘When you can shew where in the west

The phoenix builds her spicy nest,'3A misquote of the Thomas Carew poem, “Ask Me No More,” published in the mid-1600s. The original lines read: “Ask me no more if east or west / The phoenix builds her spicy nest.”

or bring me such a wooer as I can describe. But stay, before I betray my wish, promise that it shall be fulfilled.”

As she said these words, the old gentleman grasped her hand, which lay in his, so sharply, that Clara started, and, looking up, was struck by a change in his countenance, which looked almost ghastly in the moonlight that was now streaming into the room. She hastily asked if he were ill?

“No,” he replied; “but there are some allusions that one cannot hear without shrinking when they make an old wound smart again. This was one of them: at another time I may tell you why.”

“Oh, tell me now!” said Clara, anxious, perhaps, to change the subject of their discourse: “what better time than this, when all is so soft and quiet, and the glimmering twilight seems to call up the shadows of past days?—of yours I have so much to learn! You have never yet told me why you, who so often are urging me to marry, have yet remained single yourself. Come, dear papa! a story or a confession!” again taking his hand caressingly as she spoke.

He looked at her earnestly for some time in silence, until the tears stood in his eyes; and then slowly replied, in a lower voice: “I will not refuse you, my child; and you shall now listen to a story that will answer at once both your questions. It is a strange one,—so strange, that sometimes it seems even to myself as if I had only dreamed of it. There is no one but you that ought to hear it, and I am persuaded that you will neither ridicule nor repeat it thoughtlessly, for my sake and for your own.”

The grave tone in which this was said checked every disposition to mirth in his young hearer. The moonlight wavered unsteadily through the branches of the trees, and fell in restless gleams on the walls of the room, making its dark corners seem still darker. A sensation almost approaching to fear crept over Clara, and she nestled herself as closely as possible to her guardian’s side as he proceeded to relate his story in the following manner:—

“After taking the usual degree at Oxford, being an only son and independent of any profession, I proceeded to the Continent: foreign travel was then considered necessary to complete the education of a gentleman. It was shortly before the first troubles which ended in the French Revolution; but I was too intent on amusing myself to notice the signs of the times, or to have cared much had I then discerned what they portended. After rambling for more than a year through different parts of Europe, I reached Naples, where I intended to pass the winter. Up to this time I had never seriously felt the passion of love; nothing beyond a passing inclination for the amiable persons whom I had met at various points of my journey, or some light business of courtship, as easily laid down as assumed, had hitherto taken hold of me. But I arrived in Naples in a state of all others the most prone to this sudden contagion; wearied with the frequent change of careless engagements, and yet craving at heart for some object of a deeper and more abiding interest. This I was destined to find at Naples. She was one who must have been loved any where; but in the softening air of southern Italy, in a heart already yearning to throw itself away, her presence kindled a passion so sudden and vehement that it seemed at once to transform my whole being.

“She was my own countrywoman, some two years younger than myself, but already the wife of another. The husband, a querulous invalid, had been betrothed to her while she was yet a mere girl, by a family arrangement, intended to reunite some large properties. Reduced by a paralytic stroke to weakness, rather mental than bodily, he had been sent to seek for restoration in the air of Italy; and here then was his young wife, a creature glowing with spirit and loveliness, only now expanding into perfect womanhood, condemned to wear out her days with a companion such as this! At no time could she have loved him; and he was now afflicted with a sort of palsy of the mind that rendered his society tasteless and wearisome, while there was no bodily suffering to awaken the sympathies of a compassionate nature. The travelling party consisted of the married couple, a domestic physician, and the invalid’s aunt; and I found them living in the utmost seclusion, as the circumstances of the household debarred it from general society. My admission to it was purely accidental. Being distantly related to both parties (who were first cousins), I had casually seen the name in the police list, visited them as a matter of mere form, and by some chance was allowed to enter. I had never seen the lady before, but the effect of the first short interview was like an infatuation, and I gladly accepted the husband’s invitation to repeat my visits. He had been an acquaintance of mine at Oxford, and seemed to take a kind of dull pleasure in seeing me. To his wife he betrayed entire indifference, if not dislike. These were the strangely contrasted materials from which I soon became aware that the destiny of my life was weaving itself.

“What the nature of this fascinating intercourse soon became, I need not stay to describe. She, as well as myself, had a heart to give away; and the daily presence of one, who loved her with all the strength of a passion that cannot be hidden from its object, the seclusion of her life, its want of all other pleasure or interest, and the insensible influence of her fresh youth, blooming in the softest climate under heaven, all conspired to overcome her affections. The months that I passed near Sorrento, seeing her daily, but never alone, were the most troubled, and yet the sweetest, of my whole life. I could see that she was no longer unconscious and careless as at first; and the conflict between the sense of prohibition, with a necessity of reserve and concealment, and the impetuous passion that made me tremble if she but looked towards me, was softened by the feeling that she was not untouched by these emotions. How they escaped the bystander’s notice, if indeed they did so escape, I know not. One evening, at last, I was left in her company by accident for a few minutes alone. I forget what I said, or how my passion found utterance, but for the moment she yielded to its impetuosity, and suffered me to fold her in my arms and join my lips to hers: it was the first and last time. Before we were interrupted, I won from her a whispered permission to write to her, and one glance which said more than all I had dared to hope. It passed like a dream, — a brief, troubled, bewildering rapture! But dreams cannot colour the tissue of a whole life as this has tinctured mine.”

The old gentleman paused; and Clara, startled by a strain so unusual in him, expected, in silence, the renewal of his narrative.

“The natural genius of the Italians for intrigue,” he continued, “is extraordinary; I have seen nothing to equal it elsewhere. The gardener’s son, a boy hardly twelve years old, managed the exchange of letters between us with an address and secrecy that would have done credit to an old courtier: my notes were hidden in the bunches of flowers which he daily presented to his mistress, and hers were generally slipped beneath the vine-leaves at the bottom of the basket when it was returned to him, without the slightest failure or detection having ever taken place. After what had passed, concealment of our mutual feelings to each other was out of the question; as little could she affect to love a husband to whom she had never been attached, and who had been as one dead to her, almost from the day of their marriage. It seemed unlikely that he should long continue in this state; at all events, it was impossible to refrain from a thought of what might be, if ever she were liberated from this unnatural alliance. At length I obtained from her a reluctant and conditional promise that in such an event she would become mine. I know that we both were wrong; and yet, if ever a wife may be pardoned for listening to another’s love, it is in a case like this, when she is a wife in name only. The doctor declared that his patient’s restoration to his proper senses was hopeless; and I therefore made no scruple of earnestly desiring an event which would have rendered two beings happy, and relieved a third from a burdensome existence. I now see that this was unjustifiable, and will only hope that what I have since experienced may be accepted as some atonement for this and other ill-regulated wishes. But mine was a first passion, for one so incomparably lovely, and this at the age of five-and-twenty! I gave little ear then to such considerations.

“Well, this lasted for some months, and I know not what might have come of it; we both felt the restraint on our inclinations grow more intolerable from day to day: the temptation of our continual intercourse was terrible, and I was devising how I should persuade her to elope with me, when letters from home brought news of my father’s death, and compelled me to leave Italy without delay. For the moment, the shock caused by the unexpected tidings deadened all other emotions, and made me less sensible than I should otherwise have been to the pain of leaving the object of my passion, without even a farewell but such as I could take in the presence of others. Neither of us, in this trying moment, betrayed the secret; and the interchange of letters, by means of the accustomed channel, was a resource still remaining to lessen the hardship of separation.

“The succession to a large estate brought with it many duties to fulfil, and matters of business to arrange, which could not be despatched on the instant. Month after month I was detained in England, chafing with impatience to return to her whom I had left. As long as I continued to receive her letters I could struggle against it; at last she announced the departure of the family for the baths of Germany, promising to write if she could safely do so. But no letters came; and the information had been too sudden to allow of any arrangement on my part for some new means of communication. From this moment the link which united us seemed to be fatally broken: I had promised, in return for the confession which I had won from her, to do nothing which might compromise her; and was thus disabled from taking any immediate steps to recover or continue our correspondence.

“I think it was the distress of mind arising from this circumstance, added to the vexation of enduring the delays and formalities of a business which seemed interminable, that brought on me a dangerous fever; from which I slowly recovered, after passing through almost every degree of feebleness and mental apathy. Time and the languor of this disease had, in the meanwhile, produced their usual effect; and when I grew strong enough to go abroad, I had become sufficiently calm to determine that I would now finally settle my affairs, before I proceeded to execute the still-cherished project of seeking my mistress on the Continent.

“The most tedious matters which I had to settle belonged to the lordship of some mining property in Cornwall, the nature of which I need not try to explain now; it is enough to say that I had to get some deeds executed on the spot; and, as they seemed to linger in the agent’s hands, I resolved to proceed thither myself, and see what personal urgency could effect.

“The district into which this business led me is still bleak and grim-looking; but it was, in 1795, a wilder scene than I had expected to find in any part of England. The face of the land was bare, and pallid with the fumes of the mining furnaces, the refuse of which disfigured the fields for miles around. The people, haggard and ill-clothed, spoke a dialect as barbarous as that of the Basques or Montenegrins, and seemed to eye a stranger with a certain kind of fierce suspicion, or stared at him with stupid wonder. I had felt myself less of a stranger, and less unsafe, in the rudest parts of Istria, or amongst the charcoal-burners in the Black Forest. However, I found that my arrival at Redruth had tended to expedite the business in hand: in a few days it was completed, with the exception of my signature to some documents which were in the custody of a clerk of the manor court, held in the small adjoining town, or rather hamlet, of St. Dye, whither I accordingly repaired. This was on the 28th of April; but the severity of the weather, and the backwardness of the vegetation in this dismal tract, would have seemed more appropriate to February.

“The attorney whom I sought lived in a rude and ruinous-looking house, standing at the end of a long street or lane, which it closed. There was no dwelling near it, unless the rows of weather-beaten sheds, on either side of the lane, which seemed to be untenanted, could be regarded as such. If the approach to his house was unpromising, the impression produced by the owner himself was quite as much at variance with all my former ideas of the appearance and establishment of a ‘man of business.’ He was queerly and shabbily dressed, with an enormous cauliflower wig; and seemed to be about sixty years old, although his glittering eyes and the firm tone of his voice might seem to belong to a younger man. His complexion was like that of a mummy; and a prodigiously long nose and chin, with the singularity of his dress, made his aspect something between the ludicrous and the repulsive. His manner, however, surprised me by a certain decision and indifference, such as may be seen in those who have been what is called ‘adventurers,’ but were hardly to be looked for in an obscure practitioner of St. Dye.

“In the office where he received me, after the business was completed, my attention, I know not why, was caught by an enormous book, bound in faded red basil, which, as it happened to be open, I carelessly began to read. There were a variety of entries, in a formal law hand; and those which I first fell upon were as follows,—

“‘Mr. Edward Martin. The ring that he lost. Ten Shillings.’4Added missing quotation mark at the end of this line, after Ten Shillings.

“‘James Trevear. His challenge at wrestling. To win the same. A crown.’

“The next was yet more singular:—

“‘The stranger who had been shipwrecked. No name given. A message to his sister, a nun of Santander. Also her answer.’ With the remark in a different text: ‘This was a lady of great beauty.’ And, on the margin opposite, stood the note, Fifty pounds.’

“This was the most singular kind of register that I had ever met with; and I ventured to ask what was its use.

“The attorney replied: ‘It is the wishing-book: we enter the names of all who have obtained what they ask, and the price they have paid for it.’

“I looked at the man with amazement; there was nothing in his tone or countenance that betrayed the least intention of jesting; he looked steadily at me, and spoke as if he had been describing any common matter of business: his shabby clerk too, who had been called in to witness my signature, seemed to see nothing unusual in the explanation; and there was the book itself, with its unaccountable entries, lying before me. The page which was displayed was past the middle of the book; and its worn corners and soiled leaves seemed to bespeak long and frequent use. The attorney continued,—

“‘The condition is, that you declare your wish. If I can, I accomplish it at the time, or within some appointed term, not exceeding three days. The price is fixed by me afterwards; and the applicant must agree to abide by this before I do any thing. Is there any thing that I can serve you by obtaining?’

“The absurdity of the whole thing struck me as being so excessive, that, although I could not avoid suspecting that some impertinence was intended, and did not like the fixed way in which the man eyed me, I was determined to see how far it would be carried. It happened that, on my way hither, I had sought in vain, in many of the London shops, for a copy of Leo’s Masses, which, I was told, only existed in MS.; and this occurring to me at the moment, I said I should be glad to have a complete copy of his four last works, being, of course, only curious to see what reply I should receive.5MS stands for Manuscript.

“The attorney slightly raised his brows, as if in surprise at a request like this proceeding from a fashionable youth; but without making any reply, he went into an inner room, from which, in less than two minutes, he returned with a MS. in a vellum cover, which he handed to me. On opening it, I found that it contained the works I had demanded, beautifully transcribed in the old style of notation; the ink had, however, become quite brown, and the leaves were discoloured at the edges. The transcript was evidently of great age, perhaps as old as the Masses themselves. I cannot describe to you the sudden thrill which ran through me as I opened the first page. I felt as if suddenly confronted by a power, the existence of which I had never hitherto deemed possible. It was like being crossed by a ghost in noon-day!

“The attorney, without seeming to notice my amazement, said,—

“‘For this I shall demand a gold piece;’ and while I mechanically took out my purse, he tapped with his knuckle on the wainscot, and the clerk, shuffling in, seated himself at the desk, and began to engross the transaction in the wishing-book.

“In one so young and eager as I was, the transition from perplexity to the most impatient desire to try the limits of this power was almost instantaneous. The bare idea of the possibility of an access to objects which cannot be compassed by natural means is enough to make the strongest head giddy; how much more one excited by the strongest passion of the human heart, which always disposes it to transgress the ordinary limits of being. It is, indeed, the tendency of all engrossing and unfulfilled desires, to seek from the unseen world that which the conditions of common life seem to deny; but this yearning superstition, if it may be so called, is peculiarly the offspring of unprosperous love. The intensity of longing suddenly kindled by this glimpse of a new element almost overpowered me; and my voice, I know, trembled as I asked the man if he could grant me another wish. He looked at me with an expression of something like mirth, quivering about the corners of his mouth, which did not please me; but his reply was quite grave and indifferent,—

“‘I cannot to-day; it is contrary to my custom to attempt this twice for the same person; and you will observe, therefore, that a second request may bear a higher price. You should have chosen the first cautiously.’ In the meantime, the clerk had finished the entry, and deposited the book in an iron press, which the attorney locked with his own hand; then, turning to me, continued,—

“To-morrow is the 30th of April; if you are willing, after what I have just said, to employ me again, and will return to me to-morrow before noon, I will see if it may be done.’

“In a strange place like this I found it nearly useless to make inquiries respecting the man, whose proceedings had taken me so completely by surprise. No one seemed to know, or at all events would tell me, more of him than that he was counted very clever, and believed to be rich; and had a wonderful skill in discovering new veins of ore, for which he was much sought by the neighbouring mine-owners: but of the wishing-book, which I confess something like shame prevented me from directly mentioning, I did not hear a syllable. But, if such a gift as he had seemed to exercise were commonly known, it must, I thought, have been the most notable fact about him; and, in a few hours after the interview, when I began to reflect on what had passed, the warmth of my confidence became greatly reduced. But the barest glimpse of hope thrown on an impatient longing like mine awakens a restlessness not easily laid; the doubts which now began to arise did not subdue the wish, but only distressed me by pointing to its probable disappointment. I could not, however, help returning to the singular production of so scarce a relic as Leo’s MS. in a barbarous hamlet like this; and every time that I examined it, something between expectation and fear again made my hand shake, and my pulse beat quicker. What the object was, the prospect of which thus troubled me, you have already divined.

“After a restless night, I proceeded at an early hour to the attorney’s house. He made me wait for some time before I was admitted to an inner room, or office, shewing more of comfort and order than the wretched place I had seen the day before, but furnished in a way seemingly foreign to a lawyer’s pursuits: various machines were visible through the glass doors of the presses, which also contained skeletons of monkeys in singular attitudes, and several glittering specimens of minerals. He was seated at a table, with his back to the light, and did not even ask me to take a chair; but simply bowed without speaking.

“I was, however, too intent on the object of my visit to care for matters of ceremony, and at once declared what I had to ask,—namely, an immediate interview with a certain lady, beloved by me, and now absent from England.

“The attorney listened quietly, although I thought he smiled as I concluded. ‘You are not aware, perhaps,’ was his reply, ‘that many unforeseen consequences might follow the fulfilment of a wish like this.’

“‘For any to myself only I am quite prepared,’ I answered.

“’Are you prepared to pay the price—I mean the price that I may find it necessary to ask—if I can obtain what you require?’ Again I replied that I was: whereupon he again bade me observe, that he could not determine it until the affair had been completed; and then asked the name of the lady, and if she was maid or wife. I satisfied him on these points, but declined giving the surname, which he informed me was not indispensable. After this he said,—

“’I cannot attempt this without some hours’ preparation; nor will I promise any thing. If you will come at eleven to-night, I will say whether I can serve you or not. In the meantime, I must have some handwriting of the person whom you desire to see.’

“The only relic of this kind which I had then with me was a note, the most precious of all that I had ever received from her, which I always carried on my person. It was in the following words:—

“‘Why will you urge me to write this confession? You know that I am at heart, and were it not for a destiny that has made me a miserable captive, would but too gladly be altogether—Yours, ANNA MARIE.’

“No other object in the world, I believe, would have bribed me to give up this note; but I was again carried away by the vehemence of my wishes, for which I would at the moment have made any sacrifice. The old man, moreover, promised that he would return the deposit faithfully; and, as I handed it to him with a kind of pang, conned it over with the most business-like indifference, and then placed it under the hourglass which stood beside him.

“How the remaining hours of this day were spent, I do not now remember; weary and wretched they certainly were, but, like every other thing here, they passed away; and at night, after twice losing my way in the dark lanes which led to the attorney’s house, the night being cold and stormy, I stood at his door some minutes before the hour appointed.

“I was admitted by himself, and led through a side door, along a passage, to a room of some size, which the lamp he carried did not thoroughly light up. It seemed nearly unfurnished; there was another door opposite to that by which we had entered, and the wishing-book lay on a table that stood in the middle of the chamber.

“Hitherto the man had not spoken, but he now addressed himself to me, with more emphasis of manner than he had used before,—

“‘You have made a hasty request—do you still abide by it?’

“I replied that I did.

“‘And remember and agree to the conditions which I named?’

“‘Yes,’ I said, ‘and am content to observe them.’

“‘Then you will sign this engagement to that effect:’ saying which, he took from between the leaves of the book a written paper, and proceeded to read it aloud in the monotonous tone which seems to be traditionally used in the recital of legal documents. I heard something like the preamble of a common agreement, setting forth, that ‘whereas a certain service had been demanded,’ &c.; but my brain was in a whirl,—I could not constrain my attention to follow the words, and it was still further confused by the appearance, as I turned sharply round, hearing a slight noise behind me, of an uncouth-looking creature, who had planted himself close to my heels,—square-built, ugly, and dwarfish; dressed in a greasy sailor’s jacket, and red woollen cap. The attorney, observing me start at this apparition, said, without a pause or change of tone, as if he had been reading a parenthesis in the document,—

“‘It is my witness—we shall want one,’ and went forward. I could not take my eyes from the strange figure, whose chin barely reached above the table; and, in the uncertain light of the lamp, seemed to gibber and make grimaces as he took his stand opposite to me. The reading was over, although of the contents of the deed I knew nothing; and I signed it passively at the bidding of the attorney, who made me declare, audibly, that it was my act and deed; whereupon the ugly witness, standing on his tiptoes, scrawled something on the same paper with great alacrity, and then seemed to dive under the table, for I saw no more of him.

“The attorney replaced in the book the paper I had signed, and said,—

“‘I can so far fulfil your wish that you shall see the lady whom you have named; but I warn you that mischief will happen if you touch or speak to her. If you cannot control yourself, or fear to make the attempt, there is yet time to draw back. She is now in yonder room’—pointing, as he said this, to the opposite door.

“Although it was for this that I had come, and had looked forward to the interview as certain, I started at the abrupt announcement, as if I had trodden on fire. The heart leaped in my bosom, and for a moment ceased beating; my flesh crept and shivered, and my strength seemed suddenly poured from me like scattered water. But the tide of a more vehement emotion in an instant overcame these sensations. I sprang to the door, and eagerly entered the chamber. The attorney did not follow me.

“It was larger than the other, and lighted by a lamp fixed over the door; the embers of a peat fire were smouldering on a wide hearth, opposite to which, but at some distance, there lay on a couch, or estrade, of moderate height and covered with dark cloth, a woman’s figure dressed in white. I knelt over it, hardly daring at first to look at the face, which one arm partly shaded; but it was she—her very self—the same beloved being, again before me in bodily presence! but motionless, and apparently in a deep slumber. I could scarcely trust my senses in this first surprise; yet it was no vision, but her own sweet flesh and blood; living, but lovelier than she had ever appeared to me before. She was dressed simply in a night-gown, which concealed none of the rich contours of her person: one beautiful white foot stole from under the skirt of her dress, as if it had stirred while she was asleep. Her hair had escaped from the cap, of which the riband was untied, and streamed over her raised arm and across her neck in abundant tresses: from this arm the sleeve had fallen back, discovering its round and delicate form; and the loosened dress, deserting one of her smooth shoulders, scarcely concealed the soft loveliness that swelled and subsided with every gentle breath that stole slowly from between her parted lips.6“Riband” is an alternate spelling of ribbon. How can I describe the effect of this apparition so unexpectedly brought before me? My entire being was dissolved in an emotion of joy, unspeakable love, and something akin to awe and grief, mingled with a sense of ineffable sweetness and grace, such as we are at times blessed with in the dreams that give us an occasional glimpse of heaven!

“I remained for some time thus entranced in the delight of merely gazing on that beloved object; but the first confusion of feelings subsided, and I felt that this alone was not what I had sought from the promised meeting. To see her, without being recognised; to be debarred from hearing her voice, or returning one glance of her eye; with every inquiry unsatisfied, as to her present state and our future hopes; not even to know if she still remembered and loved me—was a mere mockery of my heart’s desire. And how strongly was this yearning increased by the immediate presence of its object! How I longed to speak to her, to utter something of the tenderness that melted my heart as I gazed upon her, and felt on my cheek the flow of her innocent breath! And what lover could see before him one so dear and so very beautiful, and be contented with merely looking on the lips and hands that he was dying to press? The warning was forgotten;—the condition was impossible—I could not leave her in this manner: the more I resisted the more imperious the desire to speak to her, to see her awake and turn her eyes on mine, became. I seized the hand which hung over the side of the couch; and, pressing my lips to her cheek, slowly whispered her name!

“The instant that I touched her, a tremulous kind of convulsion agitated her whole frame: she half-raised herself from the couch, and opening her eyes, which were fixed and seemingly destitute of sight, uttered a plaintive sound between a groan and a cry, such as I had never before heard, and fell back utterly supine and motionless. At the same moment, the attorney rushed into the chamber with an angry and terrified countenance.

“‘Are you mad?’ he cried, seizing me rudely by the arm. ‘Leave the room, or you will repent this folly!’ As he spoke, he threw something on the fire that instantly filled the place with a dense vapour, and rather dragged than led me into the outer apartment.

“There was a tone in that cry which seemed to paralyse my being, and echoed in it like a wail from the grave. I had not resisted the man when he forced me from beside her; and at first listened in a kind of stupified confusion to the angry words in which he complained of what I had done. But this passed away, and I was aroused by his saying, after a pause,—

“‘We have now to fix the price of this interview.’ I made no reply, but started to my feet, and endeavoured to reopen the door within which she lay; but it resisted my efforts.

“‘You will strive in vain,’ said the attorney; ‘and, if you could obtain your wish, it would merely add to the mischief you have already done. She is there no longer. You have been disappointed, but it is your own fault: it is now time to fulfil your engagement to me.’

“By this time my anger was thoroughly roused. ‘What engagement?’ I exclaimed: ‘you have mocked and cheated me! I asked to meet her—to converse with her, and you have defrauded me of every thing but a tormenting vision! I owe you nothing, your compact is unfulfilled.’

“The man frowned with a malignant expression that made his countenance almost frightful.

“‘Think again before you repeat your denial,’ he said.

“‘I say that you have deceived me, and can claim nothing, as you have failed in your promise!’

“‘Once more I ask you—’ he paused a minute, and receiving no reply, continued—’ then take the consequence! I have no more to say, nor you any occasion to remain longer here.’

“‘The presence of the man, with his cold imperious manner and vicious looks, was more than I could bear, and I gladly quitted the house, reserving the consideration of what I should further do in this matter until the morning; but the emotions which I had passed through, and the terrible disappointment I had experienced, had, for the time, utterly exhausted me, and I returned to my lodging with heavy steps, stunned and wearied, and hardly able to recollect or comprehend the scene I had just witnessed. A profound sleep overtook me, and it was nearly noon on the following day before I awoke.

“It is singular how the refreshment of sleep and the return of daylight will obliterate for a time all traces of what may have lately occupied or afflicted us during the dark hours. The languor which, in sickly bodies, is apt to succeed to violent excitement, and the tendency of the mind to wander when it is troubled by a desire that cannot embody itself in some positive act,—all contributed to perplex my remembrance of the past night. I regarded it as a kind of nightmare, during the presence of which the image of her whom I loved had been surrounded with the fantastic accidents common to that kind of dream; it had often afflicted me during the illness from which I was still by no means wholly recovered. I was weak and fanciful, and might have been the sport of some remarkable hallucination. Thus I reasoned with myself on the matter, and at length fancied that I had decided for the present to regard what had lately occurred as the creation of fatigue and fever of mind and body, and so to dispose of the question.

“At breakfast there was brought to me a Falmouth Gazette of the day previous, and after listlessly wandering over it, I was about to lay it down, when an announcement in the last page, under the head ‘Shipping News,’ happened to catch my eye. It was the report of the arrival at Falmouth, on the 27th, of H. M. Packet Columbine from Gibraltar and Lisbon; under which was a list of her passengers, and amongst these the names of the party which I had left at Sorrento, with the addition of a nurse and child. The paper fell from my hands—she was then in England—she might still be in my immediate neighbourhood! In half an hour I was driving on the road to Falmouth, which is not more than nine miles from St. Dye, as fast as the wretched horses of the inn could carry me.

“I drove to the principal hotel, where I thought it likely that I might learn if the party were still in the town, or what route they had taken on leaving it. The landlord waited upon me in obedience to my summons, but he looked troubled, and his countenance shewed no trace of the smiling and alert expression usually assumed by persons of his class. He began, before I had time to make my inquiry, by saying that he feared I should not be comfortable there for the day, as an accident had just occurred in the house which had caused great distress and confusion, and had so perplexed him that he could not properly attend to any thing else.

“There was something in this which disheartened me; but I replied that my stay would not be long, as my sole object in visiting Falmouth was to seek a relation (mentioning his name) who had arrived there from the Mediterranean.

“The man turned very white, and as he looked down, making no answer, I grew impatient, saying, ‘Will you tell me if you know any thing of the party?’ he made a doleful gesture—’What!’ I cried; ‘do you know of any misfortune having happened to Sir James—or—or to his lady?’

“The honest innkeeper attempted to reply, but at length fairly burst out a-crying, and all that I could collect was, that he offered to call ‘the doctor.’ I followed him in the hope of obtaining some relief to the anxiety which his words had awakened. On entering the room to which I was conducted, I met on the threshold my old Naples acquaintance Dr. J––––; he started on seeing me, and with every effort to command himself (he was in general composed and rather cold in manner), the tears stood in his eyes, as he took my hand and grasped it warmly.

“I asked impatiently after Anna Marie; he told me at once that she had died suddenly a few hours since, and pointed to the chamber where the body lay. I refused to believe it. I had seen her the night before so fresh and beautiful, and radiant with life!—the idea was one that my mind refused to grasp. I insisted on seeing her, and after some delay—for the doctor refused to permit it until I grew calmer—I was led into the chamber of death. She was just as I had seen her on the preceding night, save that her arms were folded across her breast, and the cheek, then so rich in its bloom, had now but a faint tinge of transparent red, and the lips were pale and closed. As I stood gazing upon her, I felt, for the first time in my life, that the bitterness of death had entered into my heart, and that henceforward the world was nothing to me but a way to the grave. I stooped to kiss her for the last time: as my lips rested on hers, the curtain was hastily withdrawn from the opposite side of the bed, and disclosed the countenance of her husband, who was sitting at the head. The former vacancy of his features had given place to the wild grimaces and rolling eyes of a maniac. He frowned and menaced me with his clenched hand. The doctor entreated me to quit the apartment, for fear of irritating him further. As we went out we met the coroner’s jury, who had just assembled, and were proceeding to view the body.

“The account which I heard from the doctor, after all was over, and I had recovered from the first violence of sorrow, was as follows:—

“It seems that soon after I had left Sorrento, the health of Sir James had begun to improve rapidly, and his mind gradually recovered its tone. One of the earliest symptoms of this change was the notice he bestowed on his lady; and as the recovery advanced, after leaving Italy, he seemed to become for the first time warmly attached to her, and behaved towards her more like a suitor than a husband. On a being so gentle and good at heart as Anna Marie was, I doubt not that this display of tenderness had its effect; and it was probably the chief cause of her ceasing to write to me. However this may be, a year after they left Naples she gave birth to a daughter; and Sir James, now quite restored to health, decided on returning to England, having wintered at Florence. The fear of an overland journey, which the troubled state of the Continent had begun to render insecure, induced him to proceed by sea to Gibraltar, from whence taking the English packet, he had reached Falmouth on the 27th of April. Here it was proposed to remain for a few days, in order that his wife and her infant might rest a little after the voyage, which had been a stormy one.

“Now it happened that on the second day after their arrival, a little before noon, the lady became suddenly afflicted with a painful restlessness and many fits of weeping; she appeared unable to bear the presence of her husband, and was altogether so changed in her demeanour, that his alarm and distress were excessive. The affection seeming to increase towards evening, she was persuaded by the physician to retire early to bed, and her maid was directed to watch in the chamber. The girl declared that about eleven o’clock her mistress fell into a soft and quiet slumber, and breathed so regularly, that she ventured to leave the room for a while, to change her dress and make other preparations for her watch. After an hour’s absence she returned, and was amazed to find that her mistress was not in the bed, nor in any of the adjoining apartments, the doors of which she positively asserted had been locked by herself, and the key still in her own pockets. After a fruitless and hasty search, she hastened in great alarm to call Sir James, who ran in the first place to his wife’s chamber. Here, however, he found her lying on the bed, apparently quite composed and fast asleep, as if she had not been disturbed for some hours. But the maid, when rated for giving a false alarm, persisted with such evident terror and sincerity in her story, that he was at length disposed to wake and question the sleeper; but this he attempted in vain. She lay, breathing indeed, but like one in a trance; and on approaching her with a light, it was seen that her eyes were fixed and wide open, and her limbs seemed unnaturally rigid, although at times a kind of shiver seemed to agitate them. The doctor, who was in attendance, was utterly confounded, and tried various means to relieve this singular affection, but without the least success. Her husband remained at her bedside throughout the night in a state of the utmost anxiety and distress, for not the slightest change took place in her condition. About eight o’clock on the following morning, a stranger arrived at the inn, and asked to see him with such urgency that he was at length admitted. Their interview was not a long one, and what passed between them will never be known. But the doctor, who had retired to take a hasty breakfast, was dismayed, on returning to the sick chamber, to find that his patient had ceased to breathe; and Sir James wandering to and fro in the apartment, utterly insane. His violence was such that some restraint seemed necessary, and in striving with him, a paper, which he held in his clenched hand, was taken from him, and preserved by the doctor. In a short time, however, this frenzy subsided, and he became quite tractable; but the shock had thrown him back into his former imbecility, and he was allowed to remain by the bedside of his wife. On examining the body, there was observed a discoloured mark on the neck, which might have been produced by some accidental cause, and was not noticed by the coroner’s jury; but I could see in the physician’s tone and manner a suspicion that it might be otherwise accounted for, looking at the suddenness of her death, and the paroxysm which had fallen upon her husband. After he had related these strange and lamentable occurrences, the doctor handed to me the paper which had been taken from Sir James. The writing I at once recognised; but what was my consternation, on unfolding the crushed fragment, to find that it was the same note which I had given up to the attorney on the day before her decease!

“The first impulse that aroused me from the stupor of despair was a desire of vengeance on the man whom I regarded as having been, by some unaccountable means, the cause of all this misery. I obtained a magistrate’s warrant for his apprehension, and myself accompanied to St. Dye the officer charged to execute it. But we found the house shut up and empty; and the neighbours either knew nothing, or would not disclose what they knew, respecting the disappearance of its tenant. I caused a large reward to be advertised for his detection, and the offer was repeatedly published for many years in succession; but neither this nor the exertions of magistrates over half the kingdom succeeded in discovering the slightest trace of the party. The matter will remain for ever a dark mystery; but the doom which fell on an erring passion, and chastised the daring of unlawful wishes, was but too painfully certain: it has been the burden of my life to this day! You now may understand why I start at any careless allusion to the subject of fantastic wishes.

“Sir James never recovered his understanding; and his death, which followed in a few years, could not be regarded as a misfortune. I rather envied his fate, for his suffering was over.

“But there still remained one living memorial of her whom I loved—the orphan child, whom I have always cherished as my own!” And, saying this, he tenderly embraced the weeping girl who leaned on his arm, and added in a lower voice, “You have already guessed, my poor Clara, that she of whom I have spoken was your own mother!”

* * * * * * * *

The above is given as it appears in the transcriber’s own notes, with such changes only as were necessary for the concise relation of the facts; their perplexing character no attempt can be made to explain, as it is impossible to discover what was real and what imaginary in the reminiscences of one who was, perhaps, a little “crazed by hopeless love.” It is, nevertheless, asserted that his ward, the daughter of Lady ––––, firmly believed in all the essential points of the narrative, for which she may have had additional reasons which are not stated in her MS. At all events, the incidents, starting upon us from the midst of real life in this nineteenth century, are sufficiently unusual to deserve some notice, whatever may be the degree of faith to which they are entitled.

J. R. CHORLEY

Word Count: 9150

This story is continued in A Musical Mystery.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Garrett Fisher

Hannah Walker

Alisa Hulme

Alexandra Malouf

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

14 December 2017

Last modified

17 January 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | “No, non voglio mai servir” is Italian for “No, I will never serve.” Clara is alluding to Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787), in which the servant Leporello longs to be a gentleman and “non voglio più servir,” serve no longer. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A “mariage de raison” is a marriage of convenience, rather than of love. |

| ↑3 | A misquote of the Thomas Carew poem, “Ask Me No More,” published in the mid-1600s. The original lines read: “Ask me no more if east or west / The phoenix builds her spicy nest.” |

| ↑4 | Added missing quotation mark at the end of this line, after Ten Shillings. |

| ↑5 | MS stands for Manuscript. |

| ↑6 | “Riband” is an alternate spelling of ribbon. |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.