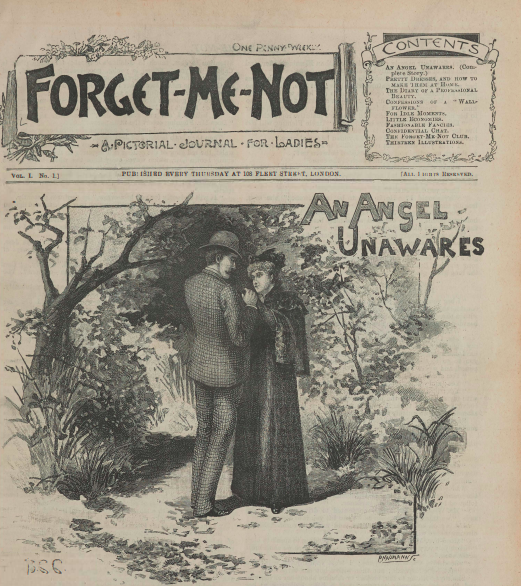

An Angel Unawares

by Anonymous

Forget-Me-Not, vol. 1 (1896)

Pages 1-11

Introductory Note: 1891 marked the release of Forget-Me-Not, a self-described “pictorial journal for ladies.” “An Angel Unawares” was written by an anonymous author, introduced as “the author of ‘Agatha’s Victory,’ ‘His Weak Point,’ etc.” and illustrated by Bernard Collier. It is the first featured story to appear in Forget-Me-Not, and accurately represents the middle-class romantic dramas typical of the journal. Its protagonist is an intriguing hybrid of the fin-de-siècle New Woman figure increasingly common during the 1890s and a much more conventional romantic heroine. With many quick plot turns and melodramatic crises, the story is an example of a “novel in a nut-shell,” in Frederick Wedmore’s terms.1Qtd. in Brander Matthews, The Philosophy of the Short-Story, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1901: 26. The story follows a young woman who struggles to define her relationship with a newly-acquainted, dashing young officer. Is it—and should it—be friendship, or love?

Advisory: This story contains an ableist slur and a brief comment on suicide.

CHAPTER I.

“Is he gone?” asks a muffled voice. “I wouldn’t for worlds break in upon your very prolonged tête-à-tête.”

“Come in, Jess,” says Miss St. Maur. “I’ve such news for you! It appears that Uncle Fleming is tired of living alone, and proposes that we shall share his home and all that he has.”

“O!” says Jess, with a sigh of delight, “we are to live at Brooklands!” Then, after a pause, she said: “When are we to start?”

“That is for mamma to decide; but Uncle Fleming wishes us to leave here as soon as possible.”

“And what will Jack Lyndon say to such an arrangement?”

“He will be vexed, of course, but I must consider my own welfare first; and Jack is so ridiculous, he would marry to-morrow if I would consent; and fancy life on a hundred and fifty pounds a year!”

“Awful, isn’t it?” says Jess, with a queer grimace and sly shrug of her pretty shoulders. “Ah! here is mamma. I leave you to break the joyful news to her. Au revoir, Addy.”

Mrs. St. Maur eagerly closed with Jonathan Fleming’s offer, and at the end of June the family travelled to Brooklands.

Adeline is speedily a favourite with her great-uncle, who likes her as well as his cold nature will allow; but Jess, who takes no pains to please him, who openly declares she loves wealth and all the good things in its train, is an object of distrust and dislike to him. She knows this, and laughs in her heart, turning a deaf ear to her mother’s remonstrances and Adeline’s plaintive reproaches.

“Let me alone,” she says brusquely. “Uncle Fleming will not live for ever, and when he is dead you will have the whole of his fortune, and be able to make Jack Lyndon happy at once.”

“I wish you would not refer so often to Jack; really you speak as though an actual engagement existed between us!”

“Are you going to deny that such is the case?”

“I have done so already to uncle. It was only a boy-and-girl affair; and in our altered circumstances I should do better than marry a lawyer’s clerk.”

“Have you told Jack?”

“Why should I? He is sure to be troublesome;” she says, leaving the room.

“Poor Jack! Poor Jack!” says Jess, resting her chin in her hollowed palms. “He deserved something better than to be made the toy of a girl like Adeline.”

With a little weary sigh she takes up her hat and goes out into the beauty and brightness of the July morning, into the deep and shady wood. The intense silence has a soothing effect upon the girl’s ruffled feelings; presently she lifts her voice in a pathetic song she has heard lately, and the clear notes go echoing down the long green glades:

“Our hands have met, but not our hearts;

I would our hands had never met—”

“I beg your pardon,” says a man’s voice close by, startling Jess considerably, “but I must beg your kind assistance;” and there, within three yards of her, half reclines, half sits a tall, bronzed, and bearded man with a frank, honest face and candid eyes.

“What can I do for you?” asks Jess. “Are you hurt?”

“Yes, I caught my foot in these brambles, and fell down with my right foot beneath me. I fancy I have dislocated my ankle, for I can’t get up unaided. Am I asking too much when I beg you to go to Alwynne House, and tell my mother what has happened, and where I am to be found?”

“You are Captain Alwynne?” interrogatively.

“Yes; and you, I suppose, are Mrs. St. Maur’s second daughter?”

“Yes; but, Captain Alwynne, do you not think you could walk with my assistance to the outskirts of the wood, and take the first conveyance going towards your home? Your injuries could be attended to more quickly then.”

She is so much in earnest that Fane Alwynne, to please her, makes the attempt.

And so with gentle hands and kindly words she laboriously helps him towards the road.

“Your sister has a lovely name,” he says; “what do they call you?”

“Jess; but I am really Jessica. If you would not mind sitting down here on this hillock, I will run to the road; I can hear a cart coming from Brooklands in the direction of Stepfield.”

And without further speech she starts at a brisk pace through the brambles and long grass. In an incredibly short time she returns, followed by a stalwart market-gardener.

“Mr. Wiseman has kindly consented to drive you home,” she says; “we think that between us we can lift you into his cart.”

He is soon hoisted into the cart, and made as comfortable as circumstances will allow.

“Good-bye, Miss St. Maur,” he says, bending to speak to her; “thank you very much for your kindness, and I hope we shall meet again soon.”

“Good-bye, Captain Alwynne; I trust your injuries will prove but slight,” she responds; and then with a bow she turns away.

She says nothing to her mother or Adeline about her adventure, and they are naturally surprised and a little indignant at her reticence when Bertha Alwynne (Captain Alwynne’s favourite sister) drives over in the afternoon to become acquainted with her, and pour out numerous thanks.

“O, I did nothing that called for acknowledgement,” says Jess, blushing furiously; “really your brother has exaggerated my performance too much.”

“It is like Jess to say so,” breaks in Mrs. St. Maur, who, true woman of the world, has always an eye to the main chance: “she does good by stealth, and is just a wee bit unconventional.”

CHAPTER II.

CAPTAIN ALWYNNE has long since recovered from his accident, and has been an almost daily visitor at Brooklands, paying great attention to Jess, much to Adeline’s disgust; for Fane (that is Captain Alwynne’s name) is young, good-looking, well-bred, and wealthy; in fact, a most desirable courtier.

One day he meets Jess at her favourite spot in the wood. After conversing for a few minutes he asks her:

“Are you going to Mrs. Reginald’s garden-party to-morrow?”

“No; I don’t like Mrs. Reginald, so I shall stay at home.”

“I believe I am not going either,” Fane says significantly. “Does Mr. Fleming escort the little party?”

“Actually yes,” and just for a moment she lifts her eyes to his.

Then they both laugh, and Jess—well, she is looking very, very pretty in her white gown, with the gold-hued roses at her throat and waist, the red glow of the setting sun lingering in the meshes of her sunny brown hair, which waves away from the white brow to the white throat, where it is gathered into a great careless knot. She carries her hat upon her arm, and her pretty face is all dimpling with smiles, for in Fane she finds, or fancies she finds, a kindred spirit.

“It will be lonely for you to-morrow,” he ventures presently.

“O no; I have Browning and Tennyson to console me and lighten my solitude.”

“And I have no one,” with a melancholy intonation; “one can’t read from morning to night. Would you be angry if I come up?”

“It would be unconventional for me to receive you,” says Jess, “and I am always too sleepy in the afternoon to do my powers of entertainment full and perfect justice.”

“I will be the entertainer—you the entertained,” eagerly. “Can a man say more? Shall I find you in the gardens—or here? The wood is just delicious in the heat of the day.”

“I do not promise to see you at all,” Jess says a trifle petulantly. “I don’t know that you have any right to ask so much of me.”

“I have no right; but I thought we were friends. I beg your pardon,” Fane answers stiffly; “I am sorry to have given you offence.”

“O, how stupid men are! how swiftly they rush to conclusions! Why, of course we are friends; and—and if you should chance to come to Brooklands to-morrow, you might find me in the gardens. But I promise nothing; you must wait and see.”

His face softens at once.

“Miss Jess,” he says, “I know the loveliest little spot in creation, and it is only three miles down the river. We could be home again before Mrs. St. Maur and your sister return.”

She is a little startled at his proposal.

“No,” she says, “I will not go; I think mamma would be so angry.”

“Sit down here,” he says. “Do you remember it was on this very spot we first met?” and with that he draws her down beside him. “Miss Jess, you hate this senseless round of gaiety as much as I do: why should we not enjoy ourselves in our own fashion? Won’t you be my companion to-morrow?” and then he turns and bends the light of his deep eyes upon her, and an unaccustomed tremor passes over her as she meets his gaze.

“If you wish it, I will go,” she says under her breath, and in her heart she is wondering why all the world has grown so fair.

She forgets the gathering dusk, the lateness of the hour, everything save Fane’s presence, until the hooting of an owl rouses her from a blissful dream. Through the over-arching boughs is seen the sable sky, lit up by hosts of glittering stars, and over the dark treetops rises the little crescent silver moon.

“O,” she says with a startled gesture, “I did not think how late it was! I must go back; mamma will be so—so anxious.”

“I am ashamed of my forgetfulness,” he says; “let us go at once.”

But it is strange how they loiter by the way, how many objects of interest and beauty Fane finds to show; but at length they reach the garden-gates.

“Please come no further; I am not afraid, it is quite light here,” says Jess, offering her hand. “Good-night, Captain Alwynne.”

“Good-night; and you will not forget to-morrow at three; I shall be waiting for you here.”

“And if you do not find me?” with a saucy glance.

“I shall come to the house and demand an audience. But I have no fear that you will fail me; I have such perfect belief in your word.”

“Thank you,” she says a little uncertainly, and so leaves him; and through all the unlovely gardens her heart is crying out one word to her, and that one word is Fane; but not yet, ah! not yet, will she confess even to that importunate heart that she loves him.

“Where have you been?” Mrs. St. Maur asks vexedly as the girl enters. “Really, Jess, you should have a little more regard for the proprieties!”

“I never thought how late it was. I have only been down to the wood; but I met Captain Alwynne, and he detained me.”

The frown clears from the mother’s brow; but Adeline says almost tartly:

“Jess is of course aware that Captain Alwynne is a rich man; that fact alone would make his attentions acceptable to such a mercenary creature as herself.”

And for once the girl is too happy to retort. Fane rich! Why, she has never given his possessions a thought!

The next day, Jess, finding herself alone, flies up stairs to make as pretty a toilette as possible, and, having arrayed herself in a pale blue cambric gown, with clusters of clove-pinks at her throat and waist, goes out to keep her appointment. Fane is waiting for her at the gate, and comes forward to meet her eagerly.

“You are punctual,” he says, smiling down at her; “and I am delighted that we shall not lose one moment of this glorious after-noon. How cool and fresh you look—positively as though you found this extreme heat in no way trying!”

“Neither do I; it suits both my health and my temper,” laughing. “It is only in cold weather that my natural infirmity of disposition renders itself obvious. You would scarcely believe me a Xantippe, but I can be on occasion.”2Xantippe was Socrates’ wife, who has become a symbol of an irritable or nagging woman.

“I certainly never believed you to be a Griselda; you are made of sterner stuff, and meekness isn’t in your line at all.”3A reference to a story in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron which relates the tale of a woman named Griselda who is put through horrendous hardships by her husband as a test of her obedience and restraint. Griselda submits to all of the trials without complaint.

“O dear!” sighs the girl; “and I fondly imagined I had hidden my depravity at least from you!”

“Perhaps I understand you better than any one else does.”

“What insufferable conceit! You have known me so short a time, you cannot have mastered all the intricacies of my character yet.”

He smiles in a superior way.

“That is your opinion, Miss Jess. Now give me your hand, and let me help you into the boat; the river is like a sheet of glass.”

Jess gives a deep sigh of delight as she takes her seat, and allows her eyes to wander over the placid water with its fringe of rushes and forget-me-nots; the undulating fields of ripening grain, where the poppies flame and burn, and the cornflowers lift their petals, blue as the cloudless sky above.

“It is very lovely,” she says, as, with a few dexterous strokes, Fane brings the boat into the shadows of the over-arching trees; “I am glad now that I came.”

“I look on myself as your especial benefactor,” answers he, resting on his oars, “I am giving you so deep a draught of pleasure.”

“Won’t you let some other person sound your praises?” Jess asks saucily, giving him the demurest look from under her hat.

“I would not advise you to give rein to your impertinence; you are quite at my mercy, and I might take summary and dreadful vengeance on you. I am not a patient fellow.”

“The man does not exist who can truthfully lay claim to patience,” announces Jess decisively; “if he did, he ought to be canonised after his death, and held up as an example to his sex forever. O Captain Alwynne, what lovely lilies! Are they quite out of reach?”

“Which, being interpreted, means you would like some? Very well, you shall not be disappointed;” and he brings the boat up to the very midst of the lovely white-leaved, yellow-hearted, blossoms. “What a lover you are of flowers! I never remember to have seen her without them.”

Jess lifts her shining eyes to his.

“They are to me what my books are—living creatures. But I like best those that are rich in perfume, however humble their appearance. Please gather no more; you have enough already.”

As he gives them into her keeping he touches and retains the white small hand a moment, and he feels her tremble under that touch, whilst a great wave of colour sweeps over her face, and as quickly recedes, leaving her very pale.

“Let us us go on,” she says uncertainly. “Is it not getting late?” and so gently withdraws her hand from his.

“Are you in such a hurry to return?” he asks in a low reproachful tone; and half against her will she answers under her breath:

“No.”

“I wish we could go on like this for ever,” Fane says ardently.

His heart is beating with unaccustomed rapidity, and it is with difficulty he can refrain from confessing all his love to the now silent girl before him. But then he has known her so short a time, and he scarcely dare believe that he could so soon and easily win this pearl of great price, this woman who has come into his life to glorify or wreck it at her will. He is a little paler than usual when he speaks again.

“Sing to me; there is no one within hearing, and I would like again to listen to the ballad you were singing on the day we first met.”

“It is very sad,” says Jess in a low, unsteady voice.

But she does not refuse his request; on the contrary, she breaks at once into the sweet air and plaintive words:

“Our hands have met, but not our hearts,

Our hands may never meet again;

Friends if we have ever been,

Friends we cannot now remain.

I only know I loved you once,

I only know I loved in vain;

Our hands have met, but not our hearts,

Our hands will never meet again.”

Jessica’s voice is not powerful, but it is very sweet, and has been carefully trained; now, in the companionship of one who understands and appreciates her, she forgets to exercise that self-control she has cultivated in self-defense, and through the clear, liquid notes there runs a tremor as of tears:

“Then farewell to heart and hand!

I would our hands had never met!

E’en the outward forms of love

Must be resigned with some regret.

Friends we still might see to be

If I my wrong could e’er forget

Our hands were joined, but not our hearts:

I would our hands had never met!”

And then, as the sweet voice dies away on the soft summer air, a great silence falls upon them which neither seems inclined to break. But at length Fane says:

“I wonder if the day will ever come when you will withdraw your friendship from me, and I shall wish I had never known you? I think if ever you fail me, you will shake my faith in all my fellow-creatures. We are friends—dear friends, Jess?”

“Yes,” she whispers, “if you wish it.”

“You know that I do—it is my dearest desire; and I am a man who knows his own mind. I shall not change.”

“Nor I,” she says in the same faint voice, the burden of love being heavy upon her.

And throughout the remainder of that long, sweet hour, which yet is all too short, she will not meet his eyes, lest her own shall tell the tale which her woman’s pride would fain conceal.

It is a very silent walk to the garden-gates: the heart of each is too full of the agitation of first love, and speech is not easy; but when Jess shyly extends her hand in farewell, Fane takes not only that, but her own sweet self into possession.

“Good-bye,” he says, “good-bye; kiss me but once, my darling,” and presses his lips to hers madly.

With a little cry she tears herself away, and, rushing towards the house, in some way reaches her own room, where, falling on her knees, she prays with tears that Heaven will make her worthy of Fane’s love. Ah! if only he could guess this!

CHAPTER III.

JESS is very miserable, and, as is usual with her, hides her misery under the guise of reckless merriment and contempt of the proprieties. For two whole days she has not seen Fane, and, remembering the kiss he had stolen, her own but ill-conceived love and agitation, she thinks with aching heart and burning cheeks that he had only been amusing himself at her expense.

This afternoon she lies in her hammock, her arms supporting her head, her lips parted in a little smile, as she holds forth to her audience of three—Adeline, Bertha Alwynne, and Bertha’s cousin, Lucy Purchas. Bertha does not think it necessary to say that Fane has gone to town on important business, and Jess dare not ask the reason of his absence, lest she should betray herself; and she would rather die than do that.

“Have you heard the news?” asks Miss Purchas, when Jess makes an end of her little mocking, merry speeches. “I don’t suppose you have yet, as it is scarcely public property.”

“You are rousing my curiosity,” says Jess. “What is it?”

“Last night,” answers Lucy, “Lady Ermyntrude Gywnne eloped with her cousin Nicholas; they are both as poor as church mice, and how they will contrive to live is a mystery. The Earl is furious, and vows he will never see either of them again. Isn’t it a romance?”

“She might have married the Manchester millionaire,” Jess laughs scoffingly. “I cannot compliment her on her wisdom.”

Bertha opens her eyes widely.

“Those who do not know you well might believe that you spoke in earnest,” she says gravely.

“And I do,” says Jess defiantly. “They say money is the root of all evil; would I possessed the root!”

“You must take all that Jess says cum grano salis,” smiles Adeline, well pleased with Bertha’s disgust.

“Addy,” Jess says sweetly, “you are very kind to endeavor to make my black white, but you know I have told you again and again that I never will marry any but a rich man; as for love, it does not exist in real life, or if ever it does, it soon dies a natural death, especially when poverty enters at the door.”

“Really, Jess, you are incorrigible!” cries Adeline reproachfully; whilst Bertha Alwyne rises, and says coldly:

“I think, Lucy, we must be going. Miss Jessica, I deplore your very extraordinary opinions, and should advise you not to air them quite so freely.”

“As Adeline says, I am incorrigible,” laughs Jess defiantly, “and can no more change my nature than a leopard can his spots.”

Bertha is so offended and disgusted that she carries her cousin off without further delay, and the sisters being alone, Adeline remarks in her usual placid way:

“You have made an enemy of Bertha, and very possibly lost Captain Alwynne, by your recklessness.”

“There are other men beside Fane Alwynne,” Jess retorts lightly, and begins to hum a sprightly air; only when Adeline is gone she covers her face with her hands, moaning like a hurt thing:

“Lost him! O Heaven! he was never mine; but what was sport to him is death to me!”

That same evening Fane returns, and Bertha, intent upon warning her beloved brother against his mercenary enchantress, takes the earliest opportunity offered for private speech. Faithfully, not adding to or taking from Jessica’s unlucky words, she tells him all, and as he listens his face grows momentarily darker. But love such as his cannot be killed at one blow, or faith so strong utterly and suddenly crushed out.

“To-morrow I will see her, and put her to the test,” he thinks. “It cannot be she is so utterly false; I cannot have been so deceived; her blushes and her agitation at least were real!”

And on the morrow he goes to Brooklands, hoping against hope, and there he finds only Adeline and her mother. Jessica is out, they tell him; so he stays but a short time, and then starts in search of her, knowing well her favourite way—through the prim old gardens, into the green and shady lanes, and there before him he sees a slight figure gracefully gowned. But even as he prepares to follow he hears a little cry of mingled fear and dismay, sees her start, swerve aside, and then stand still, whilst from amongst the bushes steps out a young fellow with handsome, haggard face. He cannot hear what he says, but he sees the girl’s hands outstretched to him; and then, scarcely understanding that he is acting dishonorably in watching the pair, he stands quite silent and motionless, full of rage and hate, of sick self-scorn and despair. If only he could hear Jessica’s words, how much misery he might spare himself and her!

“Jack,” she says ever so softly, “poor Jack! why have you come? Don’t you know yet how useless it all is? O poor boy! won’t you try to forget?”

“I can’t,” he says hoarsely, “it is beyond me! I am mad, Jess, with this anguish of suspense. I must see her; tell her I will not go away without speaking to her—that she is mine, my very own, and that I would rather lay her dead at my feet than any man should snatch her from me.”

“Jack, you frighten me, you are so violent; and Adeline will never marry you. She is not worthy your honest love. Don’t look like that. O, how my heart aches for you!”

And then, going nearer, she lays her gentle hands upon his breast, looking into his eyes with pity in her own.

“I don’t know what to say to you. Adeline never loved you, never meant to marry you; you were the caprice of an idle hour.”

“Ah, Heaven!” he breaks in. “Do not take every least ray of comfort and hope from me! She loved me once—I have seen it in her eyes and heard it in her voice. She shall love me again, I swear it! I shall call her wife yet. She is only dazzled a little while by this unaccustomed splendour; in time her own true nature will assert itself.”

“She is asserting herself now,” with profound sadness; but in his anger and despair he thrusts her aside.

“It is false!” he says so loudly that his words reach Fane where he stands; he turns and begins hurriedly to retrace his steps.

“Until out of her own mouth she stands convicted,” continues Jack more quietly, “I will never believe this evil thing of her.”

The girl answers: “Then see her yourself,” with a gesture of utter compassion. “I will not reproach you, Jack, for your injustice now that you are so wretched. And, whatever comes, I hope you will always let me be your friend.”

He hardly seems to heed her, as he says in a dreamy voice:

“I am not so poor a fellow as I was: I have had a substantial rise since you left Brixton; and Mr. Kelso has promised to take me into partnership at the close of the year. I haven’t an expensive taste; and I think Addy and I could live very comfortably on four hundred a year. Well, you tell her this, and ask her for an interview? My leave of absence is short, and if she does not arrange a meeting by to-morrow noon I shall come up to the house.”

“I think you had better not do that; she would be so angry. But I will do my utmost for you. Where are you staying?”

“At the Blue Boar; you will send me a message there to-night, won’t you?”

“Yes; and now, Jack, dear old Jack, good-bye;” and she tenders one small, soft hand, which he grasps so warmly as to hurt the slender fingers, whilst he begs her to forget anything harsh or ungrateful he may have said.

So they part, and Jess goes on what she knows is such a bootless errand. Adeline is dressing for a drive with Mr. Fleming, and does not trouble to turn her head as she enters.

“Addy, I want to speak to you. Jack Lyndon is here, and he swears he won’t go away until he has seen you. I warn you he is desperate. What are you going to do with him?”

Miss St. Maur sinks into a low chair.

“What madness is this? I will not see him; I will not so far compromise myself and damage my future prospects. You must take him a message from me to that effect.”

“I shall do nothing of the kind,” Jess retorts sharply: “you owe it to him to grant so small a favour, and I cannot see in what way you would compromise yourself by meeting your affianced lover.”

“You fool!” cries Adeline, for once forgetful of that repose of manner she has so assiduously cultivated; “do you suppose that with my splendid chances I will sink to the level of a clerk’s wife? What do you say? He is soon to be made partner, and receive four hundred per annum? Doubtless that is a fortune to him. Do you know that Uncle Fleming allows me more than half that sum for my millinery and dresses alone? I have no further use for him.”

“For shame, Adeline! you are not worthy so much as to touch his hand. I will take no message.”

With a little indignant sob catching her breath she hurries from the room, and Miss St. Maur stands looking reflectively into her mirror.

“He isn’t dangerous,” she says slowly, “but he might be troublesome; perhaps I had better write, and it will be as well to make my meaning perfectly clear. I won’t suffer any repetition of this folly. A clerk’s wife! or at best that of a pettifogging lawyer!4Pettifogging: overly concerned with unimportant details. No, thank you, Mr. Lyndon; I have other views for myself.”

And, dismissing all thoughts of her luckless lover awhile, she drives out with Jonathan Fleming, smiling and chatting as unconcernedly as though the lifelong happiness of a desperate lover did not influence her at all.

How this long, wretched day wears by, Fane Alwynne hardly knows. He has proved her false—she whom he believed so true; deceitful to the heart’s core, a clever coquette, with no mercy on her luckless lover, who is probably poor—for, of course, he has jumped to the conclusion that Jack is Jessica’s victim—and no real regard for himself.

“Thank Heaven,” he says, “I have learned my mistake in time! And yet if I had found her true as she is fair! Jess! Jess! Jess! it is such women as you who send men to perdition. How innocent she looked! how she blushed and trembled when her hand touched mine! Even now, in spite of all, I half believe her true.”

And then he moves restlessly to and fro, warring with himself and his anguish, angry that a mere girl should have such power to wound him. And just as evening is falling he makes his way to Brooklands, being sure of a welcome from Mrs. St. Maur and Adeline. The latter is walking up and down the level lawn, and turns with a smile to greet him; then, seeing how wan and haggard he is, says with soft sympathy:

“What is it, Captain Alwynne? You are looking wretchedly ill!”

“O,” half angrily, “I am not ill, only a trifle worried; something unpleasant has happened, and I am out of gear. I really ought to apologise for my intrusion; but I felt I could not stay at Stepfield, the place was so insufferably dull.”

“Uncle is always glad to have you here,” Adeline answers with beautiful propriety. “Won’t you come in and see him? He and mamma are playing chess.”

“And Miss Jessica?” he questions, trying vainly to speak naturally. “Where is she?”

“I dare not hope to account for my sister’s vagaries,” she says half apologetically. “She is probably wandering about at her own sweet will. Jess is nothing if not erratic,” and she smiles benignly.

“But she should not be allowed to wander over the country as she pleases; it is not prudent for a lady to walk so late alone.”

“I do not think I said she is alone,” answers the girl demurely. “Jess is a little witch, and certainly never lacks cavaliers.”

“You mean she is a coquette,” quietly, although indeed his heart beats madly whilst he waits her reply, which is long in coming.

“Jess is only a thoughtless child,” she said at length; “we are tolerant to her little errors. Time will mend them.”

And then, alas! for himself and Jess, he determines to throw himself on this girl’s mercy.

“I have no right to ask such a question, Miss St. Maur; but I hope you will not refuse to answer it. Who was the man with whom your sister conversed this morning, and who seemed to reproach her? I think you know what hope I have nursed; that must be my excuse for this seeming impertinence. Is he her lover?”

Adeline hesitates just a moment—only a moment—then her resolve is taken; she will kill his faith in Jess, and win his heart in the rebound. With the prettiest appearance of distress she turns to him.

“O, I wish you had not asked me that; but it is your right to know. Jess was engaged till quite recently to—ah! I need not tell you his name—but the engagement is ended now. He is only a poor man, and dear little Jess is so afraid of poverty, and incapable, I believe, of any lasting attachment. You will forget?”

“Yes,” he answers sternly, “I shall forget her, but not the lesson she has taught me. Miss St. Maur, thank you for your patience and kindness.”

The lovely eyes look into his sympathetically.

“I am so sorry,” says Adeline, throwing a world of feeling into her voice, “and if I might believe that, in spite of all that has happened, you are still my friend and will not quite desert us—”

“I have promised to dine here to-morrow,” he answers, “and I shall keep my engagement.”

“You are very brave,” says Adeline softly; and as she lets fall from about her throat and head the curious wrap of blue and crimson she is wearing she is very beautiful to look upon.

How little she thinks of the wild, wide eyes watching her, the haggard passion-marred face peering through the bushes at her! and how much less of the young sister prostrate with grief upon her bed!

CHAPTER IV.

JACK LYNDON sits alone in his room at the Blue Boar, an open letter bearing no signature before him, and as he reads those written words his face is not good to see.

Was ever a woman so heartless? Was ever a blow more cruel? Poor Jack brings his clenched fist heavily upon the table.

“By Heaven! he shall never have her!” he says. “They have spoiled her between them—my girl! my girl!”

And then his handsome haggard face falls upon his arms, and a great sob tears at his breast. But presently he is composed enough to take out what looks like a toy with its glittering mounting, but which in the hand of a skilled marksman means death, and he smiles darkly as he caresses it with an almost loving hand.

“She swore to be mine in life or death. In life she has deserted me, in death she shall once again be my own.”

Then his frenzied thoughts wander to those halcyon days at Brixton, when he had fancied himself passing rich on a hundred and fifty pounds a year, and thanked Heaven daily for the gift of Adeline’s love. Poor Jack! he has so long brooded over his wrongs, the growing coldness of his darling, her infrequent unsatisfactory letters, that he is scarcely now responsible for his actions, and this last worst blow has maddened his already excited brain.

It is now evening and already growing dusk: at Brooklands dinner is over, and the guests are amusing themselves after their own fashion. The gentlemen have entered the drawing-room, and Jess, a little paler than usual, with heavy eyes and languid mien, is seated by an open window.5Original reads “then” instead of “than.” She looks up eagerly as Fane appears. All through that tedious dinner he has not once addressed her or even noticed her presence by so much as a glance. What can it mean? In what way has she been so unfortunate as to offend him? Her eager eyes follow him now as he moves in leisurely fashion through the length of the room, until, reaching Adeline, he seats himself beside her. So it is Adeline who is stealing him away; Adeline, with her lovely face and false sweet eyes, who crushes men’s hearts as ruthlessly as she would crush a moth; who will love her lord not for love’s sake, but in proportion to his possessions. Can she bear it? Will pride sustain her through this new and dreadful ordeal? She brings her hands together with a quick gesture of pain and despair, and her heavy eyes rest with a sick sense of hopelessness upon her sister and Fane. It seems to her she must shriek out in her agony; her breath comes hard and fast, and her heart beats so loudly that she fancies others hear it too. Rising hastily, she goes out into the grounds; here, at least, she can breathe—here there is no one to gloat over her misery.

She has snatched up the nearest wrap, and thrown it about her head and shoulders: it is blue and crimson, of curious design and texture—the very one Adeline had worn on the previous night when she walked with Fane. To and fro, to and fro, with bent head and white, set, face, paces Jess, fighting with herself.

“I will kill my love,” she says to her dull heart, “but in doing so I shall kill all that is best and noblest in me.”

Then suddenly behind her on the soft sward she hears a step, the sound of which sends the colour back to lip and cheek, and she pauses, because her limbs tremble so under her that she fears she will fall. He is coming, and all will be made plain! O, thank Heaven! thank Heaven! he has sought her out. She dare not lift her eyes to Fane as he joins her.

“Why are you out here alone?” he says. “Surely it is an unusual thing for Miss Jess to lack a cavalier!”

The tone is mocking, and strikes coldly on the poor child’s heart; she looks at him then with wide, wondering eyes, and her sweet mouth quivers pitifully. But he is obstinately blind to these things, or if indeed he sees them, chooses to construe them as masterpieces of coquetry, and hardens himself still more against her.

“I got tired of the laughter and music inside,” Jess answers, with a feeble attempt to appear as usual, “and the night is so beautiful, it seemed a shame to spend it all in the house.”

“But surely you are not an advocate for solitary reflections?”

The white, wistful face is lifted a moment to his.

“I—I came out here to be alone,” she says wearily.

“That means you would rather I left you—is it so?”

“Stay if you will,” she says, “if—if you care to do so.” Then, with a sudden burst of entreaty: “O Captain Alwynne, what have I done? how have I offended you? You look and speak so differently; only a few days ago we were such friends.”

An impulse to tell her all is upon him, but he represses it, and answers lightly:

“We are friends still, I suppose; not that friendship of the present day counts for much.”

Her eyes flash with sudden fire.

“It seems to me,” she says quickly, “you can dance to any piping; a little while ago you called friendship a passion for the gods.”

“Ah! but one lives whole years in a few hours, and I have had some cruel experiences since I spoke like the fool I was. Let us be good friends until you weary of me, or—how ungallant it sounds!—I of you.”

“I would not take your friendship on such terms,” proudly.

She is leaning upon a gate, with her hands resting on the topmost rail, and she is striving with all her might to hide her suffering from him.

“I am sorry that is your decision,” Fane goes on, bent upon torturing himself, and perhaps hoping to wound her. “It is always nicer for people in the country to be upon amiable terms. And one other thing I wish to say—indeed, I sought you here purposely—is that I am unfeignedly sorry for the liberty of which I was guilty on the occasion of our last parting. I hope earnestly and sincerely you will pardon me and forget my insolence.”

Her hands drop to her sides, her wild eyes meet his full of accusation and despair, and her face is white as the fragrant blossoms she wears at her throat.

“You mean,” she says slowly and tragically, “you mean—that—that you were—amusing—yourself—at my expense. O, how could you do it! how could you do it!”

“It was only a Roland for your Oliver,” he retorts sullenly.6“A Roland for an Oliver” means a tit for a tat, an apt rejoinder or response. The expression derives from the old French legend of two soldiers, Roland and Oliver, who were set to fight a single combat to decide the outcome of a war, but were so evenly matched that neither was able to gain the upper hand.

“I don’t understand,” she says, with one hand pressed hard to her temples; “you must make it plainer, please,” in such a pitiful, entreating voice that Fane is tempted to take her to his heart, and speak the words that shall make her his own.

But the thought comes, “She is a finished actress,” and he laughs shortly.

“Miss Jess, you are not generally obtuse; you were bent upon getting some fun out of me—only—only” (and how he hates himself for the words even as he utters them!) “I am quite a veteran in such affairs.”

A low, exceedingly bitter cry breaks from her pale lips, and with outstretched arms she sways half fainting towards him; and even at that moment a man whispers to himself:

“Now, now my hour has come!” and through the still night rings the report of a pistol.

Then follows a quick shrill scream, the rushing of feet through the tangled undergrowth; and there on the grass, with arms outspread, lies Jess, a tiny stream of blood oozing from her side, staining the white of her gown, the brilliant hues of leaves and flowers around. In a moment Fane has her in his arms.

“O my darling! O my darling!” he cries, forgetful of all now but his love for her and the cruel words he has spoken—perhaps the last she will ever hear from him—“forgive me! forgive me!”

And then he is surrounded by startled, anxious guests, all eager to hear what has happened; and whilst some of the ladies shriek at the sight of blood, and the inert, slender form, and the white, unconscious face, the men for the most part start in pursuit of the miscreant.

Fortunately a doctor is amongst the guests, and all that it is possible to do is done for the unfortunate girl. In the drawing-room the ladies gather in little frightened groups, waiting the report of the medical man and the return of the search-party. The latter stray in at last by twos and threes, and it appears their quest has been almost in vain. Nothing has been found but a revolver, nothing learned save that a mysterious individual, who gave no name, has been recently staying at the Blue Boar: he had appeared very strange in his manner, and had received a letter that day which excited him greatly. The landlord, however, did not think that he was the guilty party, for, although strange, he seemed quite harmless.

Then the revolver is passed from hand to hand, until it reaches Adeline, who is standing beside Fane. She drops it hastily, and he sees that her face has changed and grown ghastly. The explanation is easy to read—she has seen what others failed to notice: the three letters scratched faintly upon the handle, “J. M. L.” She trembles so violently that Fane leads her to a seat.

“You are unnerved,” he remarks for the benefit of those near; then, in a voice so low that she alone can hear: “you know who is guilty of this outrage? It is the man she met yesterday—her rejected lover?”

“Yes,” she answers under her breath. “Captain Alwynne, do you think she will die?” and a strong shuddering seizes her as she remembers that if the wound proves fatal Jess will have been sacrificed to her callous coquetry.

With what remorse and anxiety she waits Dr. Platt’s return! how eagerly she flies to meet him as he enters!

“Tell me all!” she pants; “tell me it is not so bad as we fear!”

“My dear young lady, I am glad to say it is only a slight flesh-wound, and that Miss Jess fainted quite as much from loss of blood as from pain. If we are careful not to excite her, I think that in a little while she will be about again.”

In the relief his words give her Adeline hides her face in her hands, and bursts into the least artificial tears she has ever shed since childhood. And then comes the thought:

“I shall be safe from him now; he dare venture here no more; and perhaps I may yet be Mrs. Alwynne.”

Having heard the doctor’s verdict, the guests quickly and quietly depart. Fane walks home alone, and in his passage through the grounds the newly-risen breeze wafts something white towards him. It is the work of a moment to secure it, and as his eyes fall on the written characters his face darkens, for he could swear they had been traced by Jess. The cruel, insolent words burn themselves into his heart and brain: a woman who could send such a heartless letter to a man who loved her honestly deserved neither pardon nor pity.

“O, let her go!” he says savagely; “I am a besotted fool to remember her as I believed her. I wonder what that poor frantic fellow will do now? Commit suicide, I suppose.”

He passes a horrible night, being torn this way by his love for Jess, and that by his doubts of her truth and honesty. Rising unrefreshed in the morning, he makes a hasty toilet, and goes to Brooklands. Adeline is alone in the breakfast-room, looking lovely despite her pallor and nervousness.

“I am afraid you have not yet recovered the shock of last night’s events,” he says kindly. “You are looking very ill.”

“O, it was dreadful! I—I was afraid she was dead,” in a hushed voice; “but she has slept quietly now for hours. Mamma will not admit me yet, however; she thinks it is not safe.”

“She ought not to be excited, certainly. Miss St. Maur, you still hold to your belief as to the criminal’s identity?

“Yes, I know that he was desperate,” she answers in a queer, shaken voice, which Fane attributes to sisterly affection.

“This was enough to render him so,” he says, producing the note he had found. “I lit upon this in the shrubbery. I believe it is your sister’s property?”

She just glances at the paper with a sigh of relief.

“I think so; thank you for restoring it: it will save a world of trouble.”

“What steps do you intend taking in the matter?” he questions stiffly.

“None at all; quite against Uncle Fleming’s advice, mamma has decided to let the matter rest. Any steps to punish the offender could only result in a scandal.”

He breathes more freely. Angry as he is with Jess, entertaining such bitter suspicions of her, it would be worse than death to him to know that her name was being dragged through the courts of law, that every newspaper in the land recorded her coquetry and callousness.

“I think Mrs. St. Maur is acting wisely,” he says after a pause; then adds awkwardly, “I will be quite frank with you: but for the events of recent days I should have asked your sister to be my wife; now I am glad I did not. I would never marry a woman I did not trust fully and perfectly.

“I sympathize with you,” says Adeline, lifting her lovely limpid eyes to his, “and I hope—O, I hope—you will conquer such an ill-starred passion.”

He smiles strangely.

“That will come with time,” he says.

As he rises to go he tenders his hand to the girl before him.

“You have been very patient with me,” he says gently, “and I may rely upon you to keep my secret.”

“You know that you may,” she answers, and watches him go with a smile on her lips and a triumphant light in her eyes, for it seems to her, in her inordinate vanity, that he cannot escape her.

And as she stands dreaming of future grandeur, Mrs. St. Maur enters.

“Jess is awake and asking for you; will you go to her now? And be careful not to excite her. I must say, Addy, she is behaving extremely well on this occasion, and I do hope it will be a warning to you to avoid all future entanglements. I always told you what an ineligible Jack Lyndon was.”

“Could I guess he would prove a desperado too?” Adeline askes with a shrug of her shoulders; and then, with quaking heart and fast-failing courage, she goes up to Jessica’s room. The girl is lying propped up in bed, her bright hair straying over the pillows; her face is very pale, but her eyes shine brightly, as she motions her sister to be seated.

“Addy,” she says, her sweet voice grown very stern, “you know who it was that attempted my life.”

“Yes,” answers the other, the blood flushing her face, “it was Jack Lyndon. I suppose he meant to kill me. I am very sorry you are hurt, and—and what do you intend to do in this matter? I hope there will be no scandal.”

“You need not fear,” with unveiled scorn: “we will allow our hundred and one friends to believe I was struck down by a random shot from some unskillful marksman—there was no malice aforethought in the case;” and then a wistful look steals into her eyes. “Addy, we are not very fond sisters, are we? But you will believe me when I say I would do anything for you rather than let the truth be known; and in return for my silence, and the injuries I have sustained, I only ask that you will show the mercy to others you have not shown to Jack. You have driven him mad with your cruel wiles; he used to be so gentle and generous-hearted until you entered his life and spoiled it.”

CHAPTER V.

ADELINE shrugs her shoulders, frowns, and moves impatiently from the bedside; but presently she recovers her lost composure.

“I shall not transgress again; for my own sake, I shall be wise,” she says; and she speaks so significantly that Jess asks with a little gasp what she means.

“That Captain Alwynne admires me. I thought once you were the attraction; but he has undeceived me, and as you have no particular affection for him, I consider myself free to win him if I can.”

Every word she utters stabs the poor girl’s heart, and she could cry aloud in her anguish, only her woman’s pride sustains her. After an almost imperceptible pause she asks:

“Have you seen Captain Alwynne to-day, Adeline?”

“He has but just left, Jess. Have you quarreled with him? he speaks so strangely of you.”

“What does he say?” asks Jess, lifting herself with difficulty.

“I hardly like to tell you, because really it is very unfair; but he called you a very amusing companion for a summer’s day.”

“He is too complimentary,” says Jess, with a sense of being choked; “but it was hardly polite to criticise me so severely to my sister. However, I fortunately do not care for Captain Alwynne’s opinion—I am myself still, in spite of it.”

But for the prize at stake, Adeline would be sorry for her, because hers is a negative kind of wickedness; but at the cost of a little pain to Jess, shall she forego her heart’s desire?

“You are a dear little soul,” she says; “and when once my position is assured I shall not forget all you have done for me.”

Jess stirs uneasily in her bed.

“Give me my desk,” she says; “I want to write a letter.”

“To whom?” questions the other in sudden alarm.

“To poor Jack; I shall not rest until it is done. He will be hating himself for his mad act, and perhaps, believing he has killed you, will give himself up to the police, and then the scandal we wish to avert must come.”

Adeline loses no time in obeying her. Feebly the small white hand traces the few lines which will comfort Jack’s heavy heart, even though the writer’s generous kindness bows him to the dust.

“You will see that it is posted, Addy?” Jess says as she fastens down the envelope.

“I will post it myself. Now lie down, dear, and try to sleep.”

The slow days wear by, bringing no news of or from Jack.

“He is an ungrateful monster,” says Adeline.

“Perhaps he is ill or dead,” responds Jess tragically.

The girl’s convalescence is much slower than had been expected.

September comes before she is allowed to leave her room; but as she lies on her couch before a window she daily sees Fane come and go. Ostensibly it is to see Adeline, really to inquire for Jess, only she does not know this until long, long months after. And then there comes a night which she will remember until the close of her life. The Alwynnes are giving a great dinner, to which Mrs. St. Maur and Adeline, together with Mr. Fleming, are invited. Of course Jessica’s health prevents her attendance, and at the last moment Adeline, beautifully gowned, comes sailing into the drawing-room, where she lies.

“You are quite sure you will not be lonely?” she says, smiling; “because uncle has offered to stay with you.”

“For Heaven’s sake, no! My head aches so dreadfully; tell uncle I would rather be alone, and make the message as pretty as you can.”

“Very well, dear; good-night—for, of course, you will be asleep on our return.”

There she lies with closed eyes, thinking bitter thoughts, dreaming of what might once have been, but now can never be, until she falls into a light sleep, and the darkness gathers around and about her, as if to hide her from a world she has found so harsh.

She is awakened by the touch of a hand upon the half-opened French-window, and, sitting erect, demands:

“Who is there?”

“Do not be afraid,” answers a voice which sends all her blood to her poor heart; “it is only I, and I have come to say good-bye.”

“Good-bye!” she echoes, lifting herself among her cushions, and glad beyond measure that the darkness hides her agitation.

“Are you going away, Captain Alwynne? and for long?”

“We are ordered off to India, where it is expected there’ll be some pretty stiff fighting with the natives. I can’t say how long I may be absent; the chances are I may never return.”

“For your mother’s and sister’s sakes I hope you will,” quietly. “But is not this quite an unexpected event to you?”

“No. I have known for some days that we might be ordered out at any hour, but I would not worry my people until all was settled. I have just broken the news to the mater and our guests alike.”7Mater is a dated and informal alternative to the word “mother.”

Jess thinks of Adeline with a keen swift pang. Is it her right already to hang about Fane with all the sweet observances of love? Then she says:

“You will be sorely missed.”

He laughs mirthlessly.

“Others will quickly fill my place.” And now he draws nearer, and through the darkness is striving to read her face. “Are you almost yourself again? he asks. “I wish I could see how you look. I do not like to leave England uncertain of your perfect recovery.”

“An amusing companion for a summer afternoon” are the words that ring in her ears, and she answers in a scoffing tone:

“I am flattered by your tardy inquiry and your friendly anxiety. O yes, I am nearly myself again now.”

“Your words have not the right ring in them, nor your voice, or it may be I have forgotten how that used to sound.”

“It is not impossible,” coldly. “When do you go?”

“From here, to-morrow; from England, at the close of the week. I thought I would like to convey the news to you myself, and at the same time wish you good-bye. The last time we met we were very near to quarrelling, and I did not care to go away without holding out the olive-branch. The chances are I may never return, and I should like to feel we parted friends.”

Friends! when he has so cruelly wronged her? when, because of him, all her life is clouded? She laughs bitterly.

“Neither friends nor foes, Captain Alwynne: casual acquaintances at best.”

“As you will,” stiffly. “But once we were friends.”

“How dare you remind me of that time!” angrily. “You neither respected me nor wished my regard, and the latter you abused. Do you think I am so meek a woman as to forget all these things, and rush to accept a friendship that cannot outlast a week?”

“I certainly do not consider you meek; if you remember, you told me you were a Xantippe at times, and now I believe you,” his pain rendering him brutal. “None the less, I wish you well. I suppose some day, perhaps soon, I shall hear that you are married, and then in your new life you will cease to remember even my existence.”

“I would not marry the best man in the world,” she says tragically: “if I made an ideal of him, he would be sure to undeceive me; and if I did not idealise him, I should probably despise him. I know of no medium, so I am wise to remain in single blessedness.”

“You certainly are if you have so poor an opinion of my sex. I suppose you firmly believe that women monopolise the virtues.”

“Perhaps,” wearily; “I have not thought much about it; I don’t belong to the shrieking sisterhood, you see.8The shrieking sisterhood is a term that refers to suffragettes, especially those who are not afraid to speak up publicly. Are you going?” and now she rises. “Well, then, good-bye; I hope you will be happy and prosperous, that you will return safely to those who love you.”

“Thank you. I should have gone with a lighter heart if a dream I dreamed had been realized, a hope I cherished grown into a blessed certainty. Jess, won’t you say you are just a little sorry I am going? I would like to hear those words from you, even if I did not quite believe them.”

At the beginning of his last sentence she softens towards him, but the doubt the end of it implies rouses all her pride and indignation.

“I will not say what is so obviously untrue,” she answers swiftly. “I am not sorry; I am glad, for the daily sight of you would humiliate me to the dust.”

But he has not heard her concluding words, he has snatched up his hat and gone hastily out, leaving her to repent at leisure; and at leisure to mourn over the destruction of her hopes to draw him near.

“I was too hasty,” she moans; “I was too much afraid he should read my secret to be natural—and—and I am not a generous woman. O my love! my love! How shall I bear to live now you are gone?”

But no tears come to relieve the overburdened heart. Jess soon retires to her room, hoping her solitude will remain undisturbed; but she is doomed to disappointment. In a little while Adeline taps at her door and enters: the proud beauty’s cheeks are flushed and her eyes are full of an angry light.

“Are you asleep, Jess?” she says in a strange, hard voice. “I want to talk to you.”

“What is it, Addy? Please be brief, I am so very tired.”

“O, I’ll not keep you long. Jess, Fane is going away to-morrow. It is too horrid for anything, and in face of that he was absent nearly all the evening. I call his conduct shameful after his marked attentions to me. It isn’t likely I can wait his return from India when I haven’t a ghost of a claim upon him. We stayed the very latest we dared, in spite of uncle’s remonstrances, and just as we were leaving he came in. I was standing quite apart, but he made no hurry to join me; and when he did come to me, he just offered his hand, and said loud enough for every one to hear: ‘Good-bye, Miss St. Maur. I shall not have time to run up to Brooklands to-morrow; will you please make my adieux to Miss Jessica?’”

“Well?” says Jess laconically.

“It is not well!” crossly; “I hated him in that moment as I never hated any creature in my whole life before.”

“I don’t doubt it,” said Jessica dryly.

“The disappointment has been so bitter,” rejoins the other, not heeding the interruption. “I never shall have so splendid a chance again,” she says, leaving the room.

CHAPTER VI.

“WHAT do you think ails Uncle Fleming?” says Adeline one day in October. “He seems depressed, and so subdued that he has not treated us to any harangues on morality and propriety for these three days.”

“Is he changed?” asks Jess in that listless way which is now habitual to her; “I had not noticed. Does he complain at all?”

“No; and that makes it the more extraordinary. He mopes like an owl, and is as quiet as you yourself; he is getting an old man; perhaps it is the beginning of the end. I wonder which of us will be principal legatee, or if he will make us co-heiresses?”

Jessica’s hazel eyes flash with sudden fire.

“I would not wait for dead men’s shoes were I you,” she says sharply; “and there is something dreadful in the idea of watching for the death of one who has loaded us with benefits.”

“You used to talk differently,” complains the beauty petulantly.

“Did you suppose I meant half that I said? He has often made me angry, and I delighted to tease him by way of revenge. But I think—I think my illness has changed me.”

“It has; you are not half such good company.”

“But I am a great deal more proper, and that is a distinct gain.”

Miss St. Maur rises, yawns, and stretches out her slender arms.

“Will you drive this morning? I am going to Stepfield.”

But Jess prefers to remain at home, and so she is left alone again with her sad thoughts and her heavy heart.

Presently Mr. Fleming enters, and, remembering Adeline’s words, Jess looks anxiously towards him. How could she have been so blind to the change in him? He has lost flesh, the parchment-like face is yellower, and the cheeks are sunken. There are heavy lines about the mouth, heavy shadow under the light, dull eyes. An unaccustomed pity for him stirs the girl’s heart as she rises to meet him.

“What are you doing here?” he asks querulously. “Why haven’t you gone with your mother and Adeline? I hate to see young people so inactive. I can’t understand it—or you.”

“Never mind me,” she answers, speaking cheerfully; “I want to talk to you about yourself. Do you know that you are not looking in the least like yourself? Are you ill, uncle, or is there something troubling you?” and in her pity she lays one hand caressingly upon his arm.

But he thrusts it aside roughly.

“No, I am not ill, nor likely yet to die. Are you in a hurry to take possession of your legacy?”

She falls back with such a hurt, indignant look upon her face that his heart smites him for his cruel speech.

“I didn’t mean it, Jessica.” He says slowly and penitently. “I didn’t mean it, my child; but I am troubled beyond words.”

“Cannot I help you, dear uncle—I, who owe you so much?”

“No one can help me if things are as I fear; but there is hope yet; O yes, there is hope that the trouble I dread is of my own imagining. You are very kind, Jess, very kind,” as she draws him down beside her. “I wonder I never understood that before.”

“It has been all my fault, uncle, and I am going to make atonement. You are looking so fatigued; why do you walk such long distances alone? Let me bring you a glass of port and some biscuits, and then I will make you comfortable on the couch. You come to this room so rarely you hardly know how pleasant it is.”

“I feel better already,” he says as he sips the wine; “I think it is your society, my dear.”

It is so rarely that she has word of praise thrown to her that her face flushes with pleasure.

“We must become better acquainted, and I promise to be as meek as my natural disposition will allow. Now let me arrange these cushions for you, and when you have rested a little you will feel better and brighter.”

How curious it seems to old Jonathan that any woman should minister to his wants, should consider his comfort! Mrs. St. Maur and Adeline are always sweet of speech and manner, always ready to share any jaunt with him; but he remembers now that they have quietly ignored his ailments and his troubles, and this girl, to whom he has been often churlish, is the first to linger about him with kindly observances. Presently he falls asleep, and waking later finds Jess watching him.

“Why are you still here, my dear?” he asks with unwonted gentleness.

“I thought you might need me.”

“You are very good;” and for the remainder of the day he is much brighter.

But on the morrow the cloud falls again, and Mrs. St. Maur begins to look troubled.

“I hope he is not going to marry in his dotage—that might account for his dark looks—because naturally we should object to go now after all his promises. Or, worse still, do you think, Addy, he has been speculating rashly?”

“Certainly not that; he is too cautious and loves his money too well to risk losing it. Depend upon, dyspepsia is his ailment.”

Whatever troubles him, Jonathan holds his own counsel, and the household goes on much as usual until the beginning of a new week. Then returning one morning from a solitary ramble, Jess finds her mother and Adeline seated in deep conclave.

“O Jess,” cries the latter, “such a dreadful thing has happened! Uncle Fleming has lost all his money—there won’t be a shilling left to him!”

“What!” says Jess, surprised out of all politeness. “Do you mean that poor old man is a beggar? How has it come about?”

“Fellside & Hill’s Bank is closed, and Uncle Fleming is a shareholder—that means he will have to give all he has to help make up the deficit. O, what are we going to do?”

“Do you mean,” asks Jess tragically, “that they will cast poor uncle out upon the world, out of his own home, to starve or live on charity, and all because he is the victim of other men’s villainy?”

“That is what they can and probably will do,” Mrs. St. Maur says angrily. “But that is not the worst; we are bound to consider our own position. You know we have nothing of our own.”

“Nothing but what Uncle Fleming has generously provided.”

“I suppose he pleased himself about that,” retorts the lady sharply: “he found life alone a dull affair, and so brought us here. Well, he gave us money, we gave him the benefit of our society; I cannot see that we are indebted to him.”

“O mother!”

“Be quiet a moment, please; since I have been here I have contrived to save a little money, and I have some handsome jewellery; we can live upon the proceeds of that until you or Adeline marry; and I propose we leave Brooklands at once for some fashionable place of resort.”

“Taking Uncle Fleming with us, mamma?” asks Jessica.

“Certainly not; he has brought all this trouble upon himself and us, and must bear the burden of his own folly. I shall have enough to do to keep my head above water, without being encumbered with him.”

Jessica’s face is very white and stern, and her young head is reared high as she says:

“Where is uncle?”

“In the library, where he has been ever since the news came.”

“I will go to him; he should not be alone in his trouble.”

And neither speaks a word to stay her in her purpose. Perhaps each knows how vain it would be, perhaps each has grace to be a little ashamed.

Jess does not knock for the admission she fears might be refused, but, opening the door, enters quietly—so quietly that Jonathan does not hear her light footfall. It brings the rare tears to the girl’s eyes to see the poor old gray head bent upon the shaking hands, the whole bowed figure trembling with its anguish of grief and dread.

“Uncle,” she says ever so softly, “uncle!”

And then a blanched, blank face is lifted to hers, and a hoarse voice answers:

“Go away; I have nothing left to give you now. All the others have deserted me—I am powerless to help you—fallen—fallen—there is nothing left me now but to die.”

Then she is by his side and, kneeling there, winds her arms about his neck, drawing his poor stricken face upon her shoulder, whilst she says with a deep sob of pity:

“Uncle, I will never leave you. You have given us all we have, and it is now our turn to cherish you.”

With a trembling hand Jonathan brushes the bright hair from the white brow.

“You do not understand, you do not understand, little girl: I am a beggar, a poor old man, helpless, homeless, forlorn.”

“Not homeless or forlorn, while I live,” she answers bravely. “I am so young and strong, there are so many things I can do to earn our bread. I shall be proud and glad to work for you, dear, and we shall be happy yet.”

“Happy, with the home of my fathers closed upon me! O Jess! O merciful Heaven!” and he bursts into tears.

And she, who could not weep for her own woes, mingles her tears with his, whilst all the time she offers such poor comfort as she can.

They spend the long day together and in the evening, Mrs. St. Maur, wearing a most becoming expression of resignation and followed by Adeline, joins them.

“You have been long in coming,” the old man says with bitter reproach.

“We had so much to arrange, and we knew dear Jess was enlivening your solitude. The fact is, Uncle Jonathan, we have come to tell you our plans. Of course, under the circumstances, we cannot think of remaining at Brooklands, to rob you of the little those villainous bankers may have left you—”

“Woman, year in and year out you have lived on my bounty, faring sumptuously, going daintily clad. I have denied you and yours no comfort, no luxury; all that I have I have shared with you, for love of the dead man whose name you bear. I was fool enough to believe you cared a little for your benefactor. I thought you were sincere in your protestations of affection and gratitude. O fool, and blind, I have nothing left to give you now!” and his voice sinks to a pitiful moan. “I am a poor old man, penniless, friendless. You do well to go.” And again his rage flashes forth. “Out of my sight, woman, out of my sight! let me never look upon your face again!”

“You shall be obeyed sir; such violence is too unseemly for girls delicately reared to witness; and I may remind you that a benefit ceases to be a benefit when it is continually flung at the recipient. Adeline, Jessica, come.”

But Jess holds her ground.

“This is my place, here is my duty; you have Adeline; uncle has no one but me.”

Mrs. St. Maur is very angry, but she is ashamed too.

“You will please yourself, Jessica, but you will understand that from to-day’s decision there is no appeal.”

Jess bows, whilst the old man watches her with anxious eyes, and essays half-heartedly to put her from him.

“Choose,” says the mother coldly: “we are leaving in an hour; there is no time to lose.”

“I have chosen,” gravely and steadily.

“Then there is nothing to say but good-bye. I will write to you as soon as we are settled, and, of course, from time to time you will acquaint us with your movements. I hope you will not regret your choice. Good-bye,” lightly kissing her. “Mr. Fleming, good-evening.”

And then Adeline touches her lips to Jessica’s, and offers a dainty hand to her uncle; he takes it curiously into his own, and looks down at it with dim eyes.

“It is a lovely hand, and my bounty has kept it fair,” he says in a strange voice, “but it is a cruel hand for all its fairness. Heaven help the man who ever claims it for his own!” and he laughs grimly as the frightened girl snatches it from him and hurries from the room. Then he turns to Jess: “Aren’t you going too? You are not wise in your generation. The ship is sinking fast; make good your escape while you may.”

Jess suppresses her sobs, lest he shall think she repents her choice. The tender hands cling about his arm.

“I am not going to leave you any more; your home shall be mine, my pleasure to minister to your comfort.”

“I have no home,” heavily; “yesterday all that goodly sweep of land before us (meadow and field and wood) was mine; to-day I am a pauper, without a roof to shelter me.”

“Uncle, we shall find a home somewhere, and I will do my best to make you happy.”

He turns to her with a sudden gesture of touching gratitude.

“I have never cared for you as I should; I have neither been kind nor generous to you, and yet you alone cleave to me. Jess—little Jessica—thank Heaven I have entertained an angel unawares!”

“Not an angel,” smiling through her tears; “only a little woman anxious to do the duty she has so long neglected. And now, dear, let us try to see things clearly. I want you to tell me just as much of your business as I ought to know to be able to give you assistance.”

CHAPTER VII.

WITH great care Jonathan was removed to a pretty four-roomed cottage belonging to an old friend, Squire Holden.

There is no fear of immediate want, and Jessica’s heart grows light as she goes about her manifold duties, because of the kindness of those around.

But most depressing news arrives from Mrs. St. Maur: her funds are quickly vanishing; could not Jess help them a little?

“Soon,” her mother says, “ we shall be beggars; our hope of Adeline marrying a rich man seems to be very far from being fulfilled. Could you not come to us?”

Of course Jess returns a negative reply, and then for a time there is silence between them, and the girl wonders drearily what the end will be for them all. One day Bertha Alwynne drives to the cottage.

“I have come for you and Mr. Fleming. Now don’t say the notice is too short, for this is not an affair of ceremony; only a quiet, homely little party—ourselves, the Holdens, and Lucy. Get ready at once, and I will take you back. No refusal, Mr. Fleming; you ought to know what a resolute young woman I am.”

“My dear young lady,” with old-fashioned politeness bowing over her friendly hand, “I am but a kill-joy at best; take Jess if you will.”

“You know very well she will not come alone. O dear! what a great deal of persuasion you require! And my ponies are so fresh they will not stand long. Miss Jess, do hurry.”

And Jess having made Mr. Fleming presentable, and smartened her own toilette, Bertha drives them over to Stepfield, chatting gaily all the while lest Jonathan should break into laments as he looks on the lovely lands that once were his, but over which he now has no more control than has the veriest pauper under the sun.

The dinner is a pleasant unceremonial affair, and at its close each one wanders away to do his or her own will. Jess, who loves all beautiful things, has gone out upon the terrace to admire the pale spring sunset.

She is not too well pleased when she hears a step behind her, and a voice that speaks her name uncertainly.

“Miss St. Maur, will you be very angry if I break in upon your reverie? May I stay? It is so rarely I get a chance of quiet speech with you, I could not miss this opportunity.”

“I am going back to the house presently,” she answers quietly; “uncle believes in the old proverb, ‘Early to bed and early to rise.’”

The young man comes a step nearer. She is supporting herself now against the trunk of a tree, and her head is so placed that every line and feature of her lifted face is distinct to him; it makes his heart ache to see how its pretty bloom has faded, and he wonders where the wicked dimples have flown. The slender arms are upraised, and the small hands clasped behind her head are rough and red with toil. Vivian Holden leans forward ever so little, and touches them with his own.

“Poor little hands!” he says with infinite gentleness, “poor little hands!”

And then, before she can prevent him, or even guess what he will do, he has taken them forcibly in his own, and is pouring out a torrent of passionate words, which, try as she may, Jess cannot stem.

On the other side of the hedge which divides the flower from the kitchen garden is Bertha Alwynne, and, hearing Vivian’s mad entreaty, she pauses, never thinking that she is acting dishonorably. For a long while she has doubted if she had done well in condemning Jess to her brother, and knowing how hard he will find it to forget this first love of his life, she listens to all that passes, “doing evil,” she says to herself afterwards, “that good may come.”

“Stay,” she hears Jess say in an agitated voice; “I cannot listen to you. We have been good friends so long, and now you have spoiled it all. O! I am so grieved, so grieved! You know that my place is beside uncle, that nothing will ever induce me to leave him.”

“I do not ask that you should; if you could contemplate such a step do you think I should hold you dear as now I do, or honour you before all women? At our fireside there will always be a warm corner for Mr. Fleming; and, Jess, O my darling Jess! I hate to say it, but you shall have what settlements you please. I am a rich man, dear, and can give you all your heart desires.”

“Hush!” she says, so softly that Bertha strains her ears to catch her words; “you should not try to bribe me. If these gifts you offer could have any weight with me, it would be for my uncle’s sake; but not even for him can I give my hand where my heart could never follow. I like you; O, indeed, I think of you as a kind and dear friend; but I will not marry any man for his possessions. I dare not.”

“Take time,” he entreats hoarsely. “I have startled you.”

“If I took years and years to consider my decision it still must be the same,” she answers in a low voice.

“If you would have me resign all hope you must tell me there is some other who has usurped the place I covet. Is there?”

“You have no right to ask me that. O, I did not mean to vex you again,” as he turns away. “I will tell you what I hoped would be hidden in the grave with me. There is a man I love as the good love heaven; but if he ever knew, or cared to know, my secret he made no sign; he went away. I think he did not even like or respect me, but because of him I shall be Jessica St. Maur to the end of the chapter.”

There is silence between them then, and Bertha draws her breath lightly lest she should betray herself. Which is the true woman, this one who protests she renounces all for love, or the girl who, lying in her hammock, scoffed at love and its votaries? Has she all along been wronging Jess and hurting her beloved brother? Vivian is a wealthier man than Fane, equally well-born, younger, and of greater comeliness.

“This, then, is the end of my dream,” Vivian says at last. “You will not let me even hope that you one day will forget him and care for me, if only a little. Ah, Jess! give up this hard and uncongenial life, and come to me.”

“Ah, no! no! I will not wrong you so far, or so far do violence to my heart. Let us be friends—close and true friends—but if we are to be that you must put aside all other thoughts of me. There are other women who will make you happier than I—women whose lives lie all before them, and who will hold your true love at its dear worth.”

“Do you hope that he will ever learn the truth and return to you?” Vivian asks in a strange voice.

“I have no hope.”

“My father and Mr. Fleming will be sorely disappointed.”

“Poor uncle! But I will not—I dare not—go against my own conscience and my heart. Mr. Holden, let us part now,” and with that she tenders her hand to him.

“Good-bye,” he says brokenly. “Perhaps being a man I shall find a new love, but never so true or as dear a love as you.”

And then he goes through the fast-gathering shadows, and Jess, leaning her face against the tree, sobs brokenly:

“O my love! O my love! why cannot I forget as other women forget? How could you go without one kindly word? Fane! Fane! I wish I had died before I had ever known you!”

“Jess!”

With a cry of alarm she turns suddenly to find Bertha beside her.

“Poor dear! I have frightened you. O, how you tremble! There, lean on me,” putting an arm about the slender waist. “I have something to say to you: something to confess. I have been guilty of a most dishonorable action. I heard your voices, and I stopped to listen. Why have you refused Vivian Holden? he is the best match of the county.”

“Bertha!” and with a quick indignant gesture Jess strives to free herself from Bertha’s embrace; but Miss Alwynne is by far the stronger of the two, and holds her fast.

“Don’t be so angry! What a little fury you are! There, stand still, and let me make a clean breast of my iniquities. Do you know, until lately I believed you a horrid mercenary girl. You gave me good reason to misjudge you. Do you remember lying in your hammock one afternoon—in July I think it was—and stating your opinions with regard to love and marriage? Well, you so held to them that I thought you were in earnest; and knowing that Fane was warmly attached to you—loving him, as I do, with all my heart—I felt I hated you, and was only anxious to save him from your schemes. O, I wonder if you can ever forgive me! That same night I counselled him against you, and repeated all your idle words.”

“O Bertha!” She understands now all that had puzzled and hurt her before in Fane’s changed conduct. “And he believed you?”