Letter of a French Governess to an English Lady

The Comic Offering, or, Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth, vol. 2 (1832)

Pages 295-304

Introductory Note: This comic governess story takes the form of a letter. In it, Louisa H. Sheridan, editor of The Comic Offering, gives us a commentary on the idiosyncrasies of language. A French governess named Celestine writes to her English benefactor, recounting the mishaps she has experienced working for an English family. Her letter reads as a wittily faulty direct translation, with misleading cognates, multiple connotations, and untranslatable idiomatic expressions.

Since most educated women of the period would have studied French to some extent, the narrative might have served as a comic reminder of their own efforts. For today’s readers, we offer a few strategic translations of terminology to aid in understanding Sheridan’s humor. The resonances of her punning and mistranslation, however, are rich and multi-layered.

THOUSAND thanks, my very dear Miss, for all your goodnesses: I you assure that I myself feel quite knocked down by your amiability so touching and attendering.1In French, the first sentence would read: Mille mercis, ma très chère mademoiselle, pour toute ta bonté: je t’assure que moi-même je me sens tout à fait frappée par ton amabilité si touchante et attendrissante (translation by Corry Cropper). The narrator is translating word-by-word, rather than adapting her prose to English sentence structures and expressions. In the terminology of professional translators, she translates (and mistranslates), but she does not interpret. How you were good for me procure the situation of instructrice to the minds tenders of the youth: the childs of Miladi Bull, who are confideds to my cares, are of a beauty dazzling, and of a nature extraordinarily drawing-towards.2“Instructrice” is French for “female instructor.” “Miladi” is presumably a phonetic spelling of “My Lady,” said with a French accent.

How I am rejoiced that the cares of the tenderest of the mothers have rendered me capable of to instruct the little strangers in every branch of an education exalted; because I feel in myself that I speak and write your tongue well like an Englishe.

Helas! my best friend, some times I am not capable to repress the movements of anger at cause of the stupidity of the childs: yesterday I could not arrive to make the little Bull feel any difference for say “dessus” and “dessous,” which are as unlike that possible: I cry—“Ah! how you are beast!” forgetting you tell me that “Commes vous êtes bête,” mean “how are you stupid!”3“Helas!” is a French expression akin to “Alas!” “Dessus” means “above.” “Dessous” means “underneath.” “Commes vous êtes bête” means “How stupid you are!” Miladi Bull hear me, and fling herself into an anger frightening!

Theses littles Bull are engagings to marvel! but as to Miladi, it must that I open the heart for you on this paper friendly. Miladi Bull is quite impolished, ill-honest, starch, and not drawing-towards. She me stops from to sing when that she is present: she me defends from to wear some slippers, or some paper-curls to the hair: and she me forces of be dressed in great toilette at eight hours of the morning.4The word “défendre” in French means both “to defend” and “to forbid,” the latter of which seems to be the governess’s meaning. In the Victorian era, pieces of paper would be wrapped around strands of damp hair to dry. As says our proverb, I myself feel obliged for be “drawn at the four pins” all the long of the day, and for her please I not know “on which foot for dance.”

She me say that word “cabbage” is in very bad taste, it must say “greens” at cause of the colour: we had, the week last, to dinner some cabbage, some peas Prussian, and some cabbage-flower.5“Prussian” peas are peas with a blue tint. She ask at me—“Will you some greens:” I look to the colour of the peas Prussian, and I say—“I shall prefer some these blues.” Then she laugh of a manner horribly impolished, but without me tell that which I say bad. Then I thought she had want of some cabbage-flower; and as I could not say “green-blossoms,” I say “Will you some yellow, Miladi?” She laughed again to the clatters!6“Clatters” may be an anglicized version of the French word éclats as the French expression “éclats de rire” means “bursts of laughter.” I pray you, my dear Miss, to me tell that which I have ill said.

Green detestable!—I it hate; it goes bad with my skin brown; and I shall understand never of it the meaning! The other day Miladi Bull say—“Run very fast to the green-house, and tell Sir John for come to me:” so I put my bonnet, and run almost a half league to the alone house I ever see here painted in green:—nothing of Sir John:—I come back and find Miladi mean the “serre à fleurs” when she say greenhouse, and not “maison verte.”7“Serre à fleurs” means “greenhouse,” and “maison verte” means “a house that is green.”

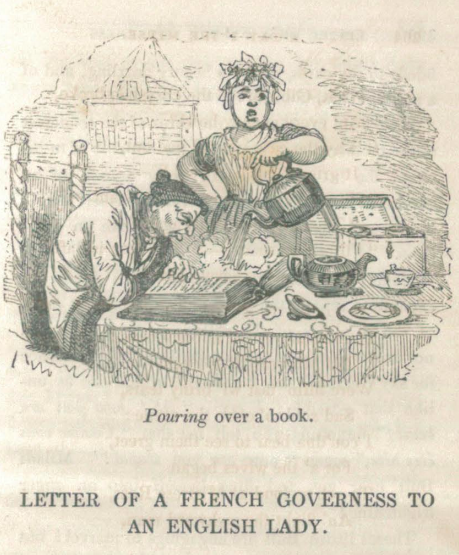

Before yesterday I was read the roman of “Red-gauntlet” of Walter (that man of the genius), when Miladi Bull enter, and making the greats eyes, she say—“You not read, you mind childs always: bring me two quills and the Canary: you forgot to water the plants.”8Redgauntlet (1824) is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott. I regard the flowers, see their blossoms tenders quite past from the ardour of the sun, and their heads elegants leaning with the indisposition: I melted all into tears at my negligence; that Walter is witch! I pour some water on the souls thirstys and faintings of the flowers, then I look in dictionary for “quill:” I find “plume,” so I run to the library where was Sir John—“Have the complaisance, sir, for give me two quills, and say me where is Canary?” (Sir John is more honest in his manners than Miladi, and always say to me “my dear.”) He answer—“My dear, Canary is a large island in the Sea Atlantique, near to the coast of the Afrique.” Eh, la! what for Miladi make me a ridicule, for me send to carry large island!

Miladi goes to a large Evening yesterday, and while she herself dress, she me sends for ribbon for her waist: she not like that which I bring, and say at me—“The ribbon shall be watered; and quill this lace on my dress.”9“Watered ribbon,” or “moiré ribbon,” is a type of silk ribbon with a wavy, or “watery” appearance. To “quill” lace is to pleat it tightly, as in a ruff. I take the dress, and think she have want for it to be garnished with feathers, as I find “quill” mean “plume.” I sew the lace and add feathers very gentille, and Miladi want ribbon watered, I make it wet with sponge, I think for make it close the waist of Miladi. Oh, la! she herself throw into an anger frightening again, and say at me that “quill” mean “tuyeau,” and “ribbon watered” mean “ruban moiré.” You have more of idioms in your tongue than I no thought.

When I arrive here, the girls dears make me to see a cat and her littles. I cry—“Oh the cat superbe, with her littles also! Oh the genteel smalls beasts!” They ask at me—“What will you say by her littles?” “I wish to say ‘ses Petits’ the littles childs of the cat, my dears loves.”

The littles Bulls laughs to the tears even, and then say that littles cats not named “childs” nor “genteels.” Sir John say at me—“My dear, you say “gentille” in French, that is “nice” in English; and my naughty girls laugh because you say “genteel small beasts,” instead of “nice little animals.”

To-day we expect some world to dinner, and I myself arranged to marvel, in a gown rose, and capped in a cap of a blue tender, garnished with buttons of roses, and teeth of wolf, and ears of hare in satin thought-coloured.10“Du monde” means “some people” in French, but literally means “some world.” I pass near to Miladi Bull, and she say at me, in anger—“What a dash you cut! why you are more like a Merry Andrew or a Jack Pudding than a respectable governess.”11A “Merry Andrew” is someone who is behaves in a silly manner in public, and a “Jack Pudding” is a foolish person.

I you pray, my dear Miss, for tell who are these gentlemen, Mr. John Pudding and Mr. Andrew, whom she named Gay? and also what she mean by cutting a dash, which I find in the dictionary “coupant un trait!” Mon Dieu! elle est drôle, cette femme!12“Elle est drôle, cette femme” means “she is funny, this woman!” “Coupant un trait” means “cutting a dash.”

At dinner she cut a large rosbif, and I say Miladi—“How you are good dissector!” She laugh (always laugh, that woman there) and say—“Not dissector, but carver.”13“Rosbif” refers to roast beef. In French, it is a slang term for an Englishman.

I do not like her contradict, but I know well that “carver” will be in French “sculpteur;” so I say only, “Thank you, Miladi, I ignoranted that;” and she laugh again.

It was there some of ladies at dinner who ask at me if I love the music? I cry, “Oh yes! I love that dear music to the folly: we had a music charming in the bosom of our family: my sister oldest can touch delightfully; my sister young pinches of a manner extraordinary; and I have a brother who gives of a style astonishing.” The lady fixed me, and then clattered with laugh. (Mon Dieu! the Englishes are very unpolished!) Then she say—“What you mean by say one touches, another pinches, and another gives, in speaking of music?”

I answer to her—“We others French say always, ‘touch the piano,’ ‘pinch the harp’ or ‘the guitar,’ and ‘give of the horn:’ my family are alls very strongs.

“Very strong!” she repeat, “what for very strong?”

“Oh!” I say, “very strong musicians:” we Frenchs say always, when one play very well.

“You French are funny people!” say the lady, and laugh again.

I forget to tell you again one mistake I have made. Sir John say, “Miss De la Roche, I must have my rubber, go and get all ready.”

I thought he want clean some pencil mark with gomme-elastique, so I bring him large piece of Indian rubber! They long time before to tell me that “rubber” will say two or three games to the whist, as much as rubber to clean paper.14“Gomme-elastique” is an eraser. Whist was a popular card game, and a “rubber” is the best of three games played.

* * * * *

Oh Miss, I pray you me procure an emplacement, otherwise; Miladi Bull has me put to the door; she has me chased of her house, and for such little of thing, also!

You know, dear Miss, that I am of a good family, and that our house at Paris, like the houses of all the nobles, was called after our name, “Hotel De la Roche:” when the woman of chambers attached my robe before the dinner, I say at her—“Oh, Mary, what number infinite of domestics I have seen at the Hotel of my papa!”

She laugh (every body laugh of me I think), and she say—“Your papa keep an hotel! Miladi papa keep an hotel also, very large.”

Eh, well! At dinner I say, “Miladi, where is the hotel that Mr. your father keep, and how you call it?”

She answer not, and makes mien to not me hear; but her neck redded, and I suppose she some person low, and her family have no hotel!15“Makes mien to not me hear” means that Lady Bull pretended to not hear what she said. “Hotel” can mean many different things both in English and in French, including a large private home or mansion, a common rooming house or pub, or even a brothel.

After the dinner, come the servant at my chamber and say—“Here is your money, Miss; go directly, as you got into a scrape with Miladi about the hotel: good night, Miss French.”

When that she go, I look in dictionary for “get into a scrape,” and all that I find is, “monter dans un gratter.” So if you find one other emplacement for me, say me at the same times what is “get into a scrape;” and believe always in the devotion entire, and the gratitude eternal of, dear Miss,

Your passionately attached,

Celestine Pulcherie Zaire Anastasie De la Roche.

Word Count: 2173

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Louisa H. Sheridan. “Letter of a French Governess to an English Lady.” The Comic Offering, or, Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth, vol. 2, 1832, pp. 295-304. Edited by Claire Nielsen. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 13 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/letter-of-a-french-governess-to-an-english-lady/.

Editors

Claire Nielsen

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Corry Cropper

Posted

4 January 2021

Last modified

13 March 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | In French, the first sentence would read: Mille mercis, ma très chère mademoiselle, pour toute ta bonté: je t’assure que moi-même je me sens tout à fait frappée par ton amabilité si touchante et attendrissante (translation by Corry Cropper). The narrator is translating word-by-word, rather than adapting her prose to English sentence structures and expressions. In the terminology of professional translators, she translates (and mistranslates), but she does not interpret. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Instructrice” is French for “female instructor.” “Miladi” is presumably a phonetic spelling of “My Lady,” said with a French accent. |

| ↑3 | “Helas!” is a French expression akin to “Alas!” “Dessus” means “above.” “Dessous” means “underneath.” “Commes vous êtes bête” means “How stupid you are!” |

| ↑4 | The word “défendre” in French means both “to defend” and “to forbid,” the latter of which seems to be the governess’s meaning. In the Victorian era, pieces of paper would be wrapped around strands of damp hair to dry. |

| ↑5 | “Prussian” peas are peas with a blue tint. |

| ↑6 | “Clatters” may be an anglicized version of the French word éclats as the French expression “éclats de rire” means “bursts of laughter.” |

| ↑7 | “Serre à fleurs” means “greenhouse,” and “maison verte” means “a house that is green.” |

| ↑8 | Redgauntlet (1824) is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott. |

| ↑9 | “Watered ribbon,” or “moiré ribbon,” is a type of silk ribbon with a wavy, or “watery” appearance. To “quill” lace is to pleat it tightly, as in a ruff. |

| ↑10 | “Du monde” means “some people” in French, but literally means “some world.” |

| ↑11 | A “Merry Andrew” is someone who is behaves in a silly manner in public, and a “Jack Pudding” is a foolish person. |

| ↑12 | “Elle est drôle, cette femme” means “she is funny, this woman!” “Coupant un trait” means “cutting a dash.” |

| ↑13 | “Rosbif” refers to roast beef. In French, it is a slang term for an Englishman. |

| ↑14 | “Gomme-elastique” is an eraser. Whist was a popular card game, and a “rubber” is the best of three games played. |

| ↑15 | “Makes mien to not me hear” means that Lady Bull pretended to not hear what she said. “Hotel” can mean many different things both in English and in French, including a large private home or mansion, a common rooming house or pub, or even a brothel. |