A Mother’s Love (Chapter 5)

The Mothers’ Treasury, vol. 19 (1883)

Pages 33-38

Introductory Note: Fred Hastings published his five-chapter short story in the 1883 periodical, The Mother’s Treasury: containing helpful hints for the household. Hastings, a congregationalist minister, wrote several short stories, amply filled with religious imagery and commentary. This tale follows the life and trials of Alexander Parder, a restless young man who has grown tired of his small village in Bristol and decides to abandon his family and embark on a ship in search of adventure. Laden with Christian themes and Bible references, Hastings crafts a tale about forgiveness and the rebellious nature of mankind that resembles the well-known “Prodigal Son” parable.

Advisory: This story contains racially insensitive terminology.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the third of three parts:

CHAPTER V.—REDEEMED

Two further tedious and laborious years passed away on the plantation. See him at the end of that period toiling ’neath the sweltering sun, hard and silently, in the field. A harsh summons falls on his ear. Shouldering his hoe, he hastens timidly to the overseer. “Come with me,” says the stern man. Alec follows, wondering whether some punishment for some imputed negligence may not be in store for him. He shudders at the thought of the whipping post. Round to the front of the house he is led. He sees there a gentleman holding his horse, and chatting kindly to the planter’s daughter at the doorway. The planter had just gone within to see what price he gave for Alec. The little girl who was her father’s pride and joy, held by the neck a ferocious dog. The child was interested in his stranger, and readily answered some of his queries concerning the white slave.

Alec began to guess as he caught sight of the horseman why he had been called from the field. Some one, he thought, wants to purchase me and the planter will be willing to part with so troublesome a hand as I am. The prospect of merely having a change of masters quite caused a flush of joy. He stood timidly at a distance until the planter reappeared.

“Perhaps this is the one you are seeking,” said the planter to the stranger, when he came out and called up Alec.

With the bridle of the horse over his arm the stranger goes up to the slave, takes hold of him by the shoulder, and looks most searchingly into his face for several moments.

“You have not always been a slave, have you?”

“No, sir,” Alec fearingly replies.

“Are you an African.”

“No, an Englishman.”

“From what part of England did you come?”

“From Somerset.”

“Is not your name Parder?”

“It is, sir.”

“Alexander Parder?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Thank God! Oh, thank God! Found at last! Do you not know me, Alec?” eagerly asks the stranger.

To hear his name mentioned in that manner melts the heart of the almost despairing man. He recognizes home accents. Surely, he thinks, it must be my elder brother! At length, half fearful lest his sense deceived him, he says, “You are very like my brother Cris., only so much older.”

“I am he! Oh, Alec, how I have sought for you! How rejoiced I am to have found you. I can hardly believe it! How glad our dear parents will be to know that I have found you! What a search I have had! In Australia, and at the Cape, and in this great land.”

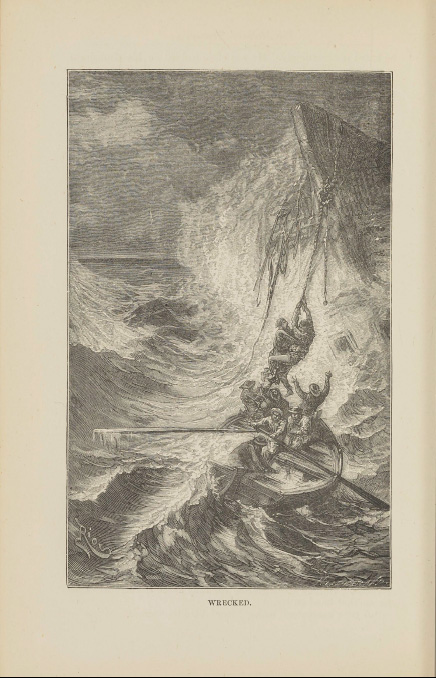

The well-dressed stranger grasps with both his hands those of the slave,—the long lost brother,—bends his head on his shoulder, and weeps tears of joy. Alec, throwing back his head, looks up through moistening eyes to heaven, and says, his lips quivering with intensest emotion, “O God, Thou has heard my prayer at last! I bless thee.” What more he murmured of thankfulness none could catch. Utterance seemed choked, his heart overflowed with joy. “News from a far country” had come at last. More refreshing even than the “cool waters” which, when perishing with thirst, he had found oozing from the rock on the morning after his shipwreck, was the sight of one bringing tidings from a far country.

But before the slave can be given up to his brother, the planter must be reimbursed that which he had given for him. He set a high value upon him. Hitherto Alec had been accounted the most useless slave on the plantation; now, because there is the prospect of a good price being paid for his ransom, he is the best. Exorbitant was the price demanded. He had spent so much in finding Alec that he had but a few English sovereigns to offer. These the slave owner would not accept as sufficient. Cris. told the planter the story of his search, but the hard man saw only now the prospect of making still more by his bargain. Christopher tried to get him to let them leave, promising that he would send the money, but the appeal was useless. One or two ways only out of the difficulty presented themselves. Either Alec must remain until he should send for the money from home, or he must take Alec’s place and send him to England. After another attempt to persuade the slave owner to trust them to send the money, Christopher proposed to take Alec’s place. The slave owner said it did not matter to him if he became Alec’s substitute, if he only could do as much work as Alec. But Alec protested against this. Moreover, he said, that as he had become accustomed to such severe toil under the burning sun he could better bear its continuance than could his elder brother. But Christopher insisted upon taking Alec’s place for a day to try it. The owner consented to this, and Cris. went forth with the gang of slaves to the cotton field. Alec remained in his hut for a short time after Christopher had gone to the field and then he followed him. As he saw Cris. lifting the heavy hoe and toiling hard to keep pace with the others, he could not bear it. He went and forcibly took the hoe from Christopher, and said:

“You shall never bear all this for me, I am not worthy of it, I will rather die than that you should do it.”

Christopher had to yield to Alec at least for that day, but the next day, the latter was smitten down with a fever, the result of excitement and exposure. When he could not go forth the owner blamed Christopher for hindering. He offered to do what he could for his brother’s lack, and when Alec recovered Christopher would still go down to the field, and keep as near to him as possible, cheering him with the hope that the money would soon come, and they would both go home. Thus for three months did Christopher wait, working at some carpentering to earn the food and shelter he received from the slave owner. He would not go back without Alec. As they at eventide strolled together, Christopher told his long-lost brother how it was he had found him; of how one day there came to his father’s house a rough-looking sailor, who said, that he had something most important to communicate to Mr. Parder concerning his absent son, and how he bargained first for a good sum to reveal his whereabouts. “He told us,” said Cris. to the deeply attentive brother, “that he had been one of the crew of a slaver; that you were captured and sold as a slave; that while on board you had told him your name and the name of the place where you had lived, that you had been disappointed by the faithless captain; that he could not help feeling sorry that you, a white man, should be degraded to the position of a black; that he, having left the slave trade, and made up his mind to try and deliver you; that he had learnt the name of the dealer who had bought you, and that it would not be difficult to track you. What joy did it cause our dear parents to hear even this of you! Mother had been gradually sinking, and we feared we should soon lose her, but the ‘news from a far country’ was like balm to her anxious spirit.”1The quote is from Proverbs 15:25.

Further, Christopher, continuing his story, told how,—acting upon the clue given by the sailor,—he had gone from one place to another, and from one dealer to another seeking the lost one until he found him. Alec listened to the recital over and over again, asking various details and looking each time with deeper and deeper love on one who had so faithfully followed him until he had found. His joy at the thought that he had such a brother was so great that he was almost content to die, so long as that brother might sit by his death-bed. He told the other poor slaves, when down at old Matt’s hut, of his brother’s perseverance, love and faithfulness. Old Matt broke out, “Oh, dat is just like the blessed Lord Christ, who came to seek and save us from death and hell. He paid de debt for us. He holy and no sin in self. We hab de sin. He get de right to set us free. He no leave us for de blood hounds of de devil to track us. He made quite safe. We can do nothing but just trust and lub ’im for all de marcy.” Cris. went to the meeting and heard all this, but he was not allowed to speak to them. Being a white man the jealously of those days would not permit him to talk to the slaves lest he should make them the more dissatisfied with their lot. How he wished he could have bought them all and have given them their freedom. He could not do that, but we may be thankful that Christ the Great Saviour has power to save the whole race of men; he delivers them from the curse of a broken law and hopeless slavery to sin by the sacrifice of himself. There is no limit to the worth of his work and merit of his great sacrifice. He came, not only to seek, but to save the lost.

At last the money which was to redeem Alec arrived. Christopher took it to the slave master himself. Had he gone away and sent it, that hard hearted man would have kept both slave and money. Christopher would not stir until he had a paper giving him a clear right to his brother as his owner. Had he not taken this precaution Alec might have been seized and sent back as a runaway slave. Alec had to act as a slave until they were both safe on board an English ship, and in passing through the slave states there were many suspicious looks and keen enquiries as to the right of Christopher to take Alec with him. He could not change the slave-garb of Alec at once for more decent clothes. To attempt to purchase them was to provoke enquiry, Christopher obtained it at last and Alec threw off the defiled rags of slavery never to put them on again. Thank God that now the horrible slave system is abolished from one end of the States to the other.2Slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865.

On board the English ship, both felt safe as if they were already in their loved land. They looked up to the flag overhead with pride and joy, for it was in the third year after abolition of slavery in all the British possessions that they sailed from America.3The purchase of slaves from Africa was abolished in 1807, but the slave trade wasn’t abolished in all British territories until 1833.

As the ship came up from the Severn to Bristol, Sandpoint was passed. The brothers could clearly see the old square tower of the farm house. Alec begged to be put on shore, but the tide was running fast and the wind favourable, so that it would have been a risk to remain to send the boat ashore. Alec seriously meditated trying to swim to land, Christopher dissuaded him. Past Clevedon,—then but a scattered village,—and up the Avon they sailed. As Alec looked at the noble red crags and softly tinted woods that fringe the beautiful winding river, he thought he had never seen anything so romantic and grand. He felt he must almost kiss the very ground, so dear seemed the soil of his own native land after his long absence and slavery.

No railways existed by which to come into Weston at that day, so the brothers took the coach to the nearest possible point and then walked to their home. They passed through Worle and over the flat to the homestead so familiar and dear. There at last is the old house with its ecclesiastical appearance, and the farm, whose curious timbering had been such a charm in his early days. Their father saw them coming over the fields, knew Christopher, and was sure that the one with him was Alec. Without saying a word he hurried off to meet them, and came to them as they arrived at the gate of the field nearest the house.4This description of Alec’s father mirrors that of the father in the Prodigal Son parable. Who shall describe the joy of father and sons, or the further joy when all went inside to meet the mother who had so hopefully waited and fervently prayed for the return of her wandering boy?

Alec’s health had been much broken by all his exposure and toils, but under the care of his loving mother, he gained more strength and was able to occupy himself about the farm. He did not neglect his Bible now, but read it eagerly as a revelation of God’s love. His experiences when in slavery had prepared him to trust in Christ fully, and when he cast himself entirely on His mercy he realized a peace and joy superior to that he had felt when first found by his faithful brother.

Alec never forgot his obligations to Cris. The two brothers became inseparable. Alec sought only to do that which would please his elder brother. When their father died, the two still kept the farm, supporting their loving mother and cheering her declining days by every means in their power. She was happy beyond expression as she rested in their love.

Word Count: 2394

Original Document

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Frederick Hastings. “A Mother’s Love (Chapter 5).” The Mothers’ Treasury, vol. 19, 1883, pp. 33-8. Edited by Julia Bryan. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 20 February 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/a-mothers-love-chapter-5/.

Editors

Julia Bryan

Reagan Argyle

Salem Valiulis

Posted

9 March 2023

Last modified

19 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | The quote is from Proverbs 15:25. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865. |

| ↑3 | The purchase of slaves from Africa was abolished in 1807, but the slave trade wasn’t abolished in all British territories until 1833. |

| ↑4 | This description of Alec’s father mirrors that of the father in the Prodigal Son parable. |