The Alchymist

The Library of Fiction, or Family Story-Teller, vol. 1 (1836)

Pages 240-257

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: The Alchymist is a melodrama that tells the story of Ricciardo, a poor young alchemist who struggles unsuccessfully to synthesize gold in hopes of providing for his family. One rainy night, a wealthy old man, dying from a knife wound, takes shelter in Ricciardo’s home. Ricciardo must decide whether to report the murder to the authorities or quietly take possession of the old man’s riches, questioning whether this turn of events is a matter of providence or a temptation. Published in The Library of Fiction or Family Story-Teller, a periodical aimed at the casual reader, The Alchymist explores themes of greed, deception, guilt, pride, and repentance.

Advisory Note: This story contains a depiction of suicide

The incident which forms the groundwork of the following tale, is taken from an undated manuscript, in the library of a French nobleman; and is evidently the same on which Mr. Milman has founded the plot of his Tragedy of “Fazio.”1A tragic play by Henry Hart Milman about a man whose love for his wife’s sister leads to disaster.

DURING the civil wars of Genoa, which drove so many of her citizens to seek an asylum in other states, an Italian, named Grimaldi, took up his abode in Pisa. The refugee was a man whose idol, from his youth upward, had been gold; and, with the firmness of a true devotee, he would have remained to perish in his native city, had he been unable to succeed in transporting with him his god. Accordingly, the few coffers which accompanied him, and which contained, as he said, his scanty wardrobe, were reported to enclose a heavier and a richer lading; and the aspect of yearly-increasing poverty which he assumed, and which was in direct contradiction to his unceasing (and, as was well known, productive) industry, had the unwelcome effect of making him to be supposed richer than, perhaps, he really was. Like many another of his class, this wretch was the victim of a caution which overshot its mark. His miserable fare and tattered garments could impose on no one, in a city where his accumulated usuries were known. His increasing care to appear a beggar, was held to be the measure of his increasing wealth. His superabundant precautions to defend his dwelling against the robber, were a signal to the robber that it contained much which would repay an attack; and the utter solitude in which he lived and moved (at once from fear and avarice) was the very circumstance to facilitate the enterprises of the thief whom his rumoured hordes might attract.

One evening, as he was returning late to his lonely dwelling, after a day on which he was known to have reaped a rich harvest from his unholy traffic, Grimaldi was suddenly struck by a poniard as he turned into a narrow street and passed within the shadow of an overhanging upper-story.2A poniard is a small dagger. The blow, which was no doubt intended to have been instantly mortal, as the prelude to robbery, had not been delivered with a hand sufficiently steady to ensure that effect: and the miser, under the impulse of a fear which was ever, more or less, present to him, (and now at length sufficiently justified), had strength left to fly from this substantial murderer, as he had often before done from shadowy ones. The night was stormy, and the street utterly dark—save at its further extremity, where it was crossed by a line of vivid light which streamed outward from a half-open door. Towards this welcome beacon the wounded usurer fled, in the strength of a terror which drowned the sense of pain (though, apparently, he was not pursued); dashing aside the unresisting door, and rushing through the outer apartment into an inner chamber communicating therewith, from whence the light issued, he presented himself, amid the glare of lamps and the glow of a huge furnace, before the eyes of its astonished inmate—with the dagger still remaining in his wound, and features on which the most sordid amongst the human passions were maintaining a desperate struggle (but which was evidently to be an unavailing one) against the strong hand of death.

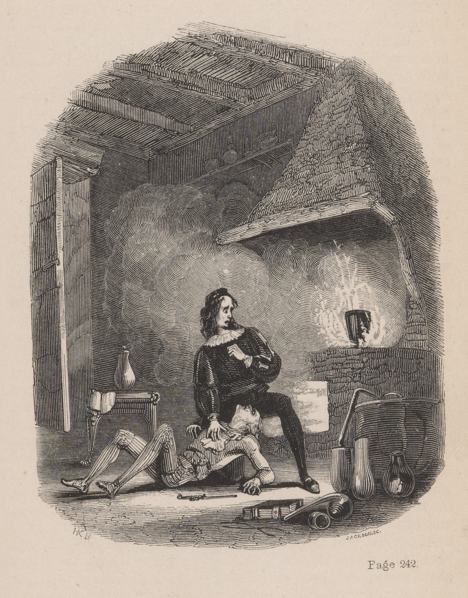

The apartment into which the dying usurer had thus abruptly and fearfully intruded, was the work-room of a goldsmith named Ricciardo; who, all his life, had been, like Grimaldi, a seeker after fortune, but by far other means and with far other success. No two subjects of the same idolatry could well have been of dispositions more diametrically opposed. Gifted with a keen intellect and an ardent temperament, with strong passions and acute sensibilities, the spirit of Ricciardo thirsted after gold,—not, as did the miser’s, for its own sake, but for the sake of all which it could minister to those passions and those sensibilities; and the energies of his powerful mind had long been employed in an endeavour to snatch from science the secrets by which (like many another enthusiast of his time), he believed that the precious metal which he coveted might be obtained. Love—which, in a breast like his, was an overmastering spirit—had, in spite of poverty, early linked to his hard fortunes a wife and two children; and, goaded on by their necessities—in addition to his own desires, his youth was wasting away in the eager search after the philosopher’s stone.3In the original, the em-dash is made up of three hyphens. All of the following em-dashes will be corrected accordingly. The slow but more certain process by which the usurer transmuted the wants of others into the precious metals for himself, was ill adapted to the Rosicrucian spirit of the enthusiastic goldsmith; and the last remnant of his exhausted fortunes was at length staked upon that final venture which was, in its result, to leave him a beggar, or open up for him the path to boundless wealth.4Rosicrucianism is a European spiritual movement involving mastering one’s life and living in harmony with the world. On the night in question his family had been removed, under pretence of visiting a sick relation of his wife; and Ricciardo sat alone by his glowing fire, wrapt in the dreams of alchymy, and watching, with a throbbing heart, for the hour of projection, which he believed to be at hand. It was to temper the suffocating air flung from the intensely heated furnace, that the door of his outer shop had been left open to the street.

The kindly nature of the goldsmith was readily aroused from his own engrossing speculations, by the fearful spectacle which so suddenly presented itself before him; and, after a few words of hurried inquiry and broken explanation, he applied himself, even amid this crisis of his own fortunes, to render to his neighbor such aid as might be in his power. Having made due provision for staunching the blood which was likely to follow, he set about the attempt to extract the weapon from the breast of the wounded man. The fears and struggles of the usurer rendered this a task of some difficulty; and when, at length, it was accomplished, the operation was not followed by the expected stream. The muscles of the face, however, which had been tightened by the spasms of pain, were fast relaxing; the dews of death were gathering thick and heavy on the miser’s brow; and it was obvious to the goldsmith that the hemorrhage was internal, and the wounded man beyond the reach of remedy.

Amid the insane terrors of the dying wretch, it was difficult to get from him any particulars which might throw light upon the event, the issue of which was so fast approaching. From his incoherent ravings, however, and in answer to the anxious inquiries of the goldsmith, the latter gathered (as he believed), that the sums which the usurer had that day received,—and which had, no doubt, tempted the assassin’s blow,—had been deposited in his home, previously to his last departure therefrom, and that the murderer would, therefore, have missed his booty, even had his arm struck with more instant success. It was while the alchymist thus hung above the dying miser, occupied in soothing his anguish and speaking peace to his fears, that he was startled, as if a trumpet had been blown close to his ear, by the sound of a low hissing, whose import he too well understood; and turning, with a thrill of anguish, to his neglected crucibles, he perceived that the moment of projection had passed by, and his children were beggars! A heavy sickness shot to the heart of the disappointed and ruined man,—which was succeeded by a space of entire unconsciousness; and when, at length, he awoke from his syncope, and rose up with the slow measured action of despair, all in the chamber was silent and still. The glowing heat of the furnace was almost extinguished, in its own ashes; and, by the misty light of the untrimmed lamps, the alchymist saw that the sordid spirit of the miser was gone, and that the wretched body before him had undergone the great transmutation.

Closing the door which gave access from the street, the goldsmith sat down to brood over his ruined fortunes. The body of the usurer lay where Ricciardo had placed him, previously to extracting the poniard; and, with this dismal object before his eyes, and in the half-dreaming mood into which he now speedily fell, (exhausted by the intensity of the last hour’s sensations), it was natural enough that thoughts of the murdered man should become inextricably mingled with reflections upon his own desperate condition. The sudden apparition, and awful death, of the rich miser, were strangely blended with his loss of the grand arcanum; and the very instant of time which had so cruelly mocked his own thirst for gold, (when, as he verily believed, the draught had been within his reach,) had quenched that same thirst in the usurer’s breast for ever. The same hour which had taken from the strong living man and father, his last fragment of wealth, had (before his eyes, and in a manner so closely connected with that event as to make the two operations seem almost identical,) left hordes of that same wealth masterless and unclaimed. The instant of projection, for which he had watched so anxiously and so long, had (in his very presence and by means conspicuously appealing to his imagination), been signalised by the sudden removal of one who had heaped up large treasures of the precious metal which that same instant had promised to his hopes. There was something in the coincidence which was sufficiently striking; and the mystical tendencies of the goldsmith’s mind led him to see even more in it than might be reasonably suggested. Strange thoughts passed, wildly and unmarshalled, through his visionary spirit; and when, at length, he sank into a restless slumber, his dreams alternated between the pale faces of his famishing children and the red gold of the murdered miser.

A sleep thus haunted and troubled could not endure long, and the goldsmith was soon startled back into consciousness by the voice of the increasing storm. The lamps and the furnace had alike burnt out, and the flashes of lightning gave momentary glimpses of the awful thing which was his companion in that dark and silent chamber. The first movement of the goldsmith’s re-awakened mind, was one of pity for the wretch who had met with so sudden and fearful a fate; but this was speedily exchanged for a feeling of uneasiness at his own singular situation. Rallying his powers for reflection, he felt that uneasiness by no means diminished by a further review of the strange circumstances in which he was placed. The tempestuous state of the weather had cleared the streets, at an early hour; and he was the sole witness of the miser’s death, and the sole depositary of his tale. The notorious wealth of the usurer, and his own poverty and anxious pursuit of gold, rendered it by no means a safe thing for the alchymist that the former should be found murdered in his house, and with every presumption that the murder must have taken place there,—since the streets had not been alarmed by the event, and none but the goldsmith could give any account of it. He saw, too, that the business on which he had been engaged when the wounded usurer appeared before him, by preventing his summoning his neighbors to his aid, would fearfully strengthen the suspicions which must inevitably be excited against him. It was incredible, (he felt that it was so), upon any other presumption than that of his guilt, that he should have suffered the wounded wretch to die in his chamber, without calling for relief to his sufferings, and witnesses to his deposition of facts. Thoroughly aroused to a sense of his own danger, the goldsmith proceeded to strike a light; and, in an agitation which, for the moment, overcame the sentiment of his own disappointment, set about a rapid examination of the body. The corpse was a loathsome spectacle. The grudging spirit of the miserable man had reached into the grave, and cheated the worms of their appointed repast by making a skeleton of his body during life. But the alchymist had far too deep an interest in other objects of his search, to encourage the disgust with which his unclean task inspired him; and, one by one, he deliberately proceeded to examine the thread-bare garments of the deceased. A bunch of massive keys was the only article which they yielded to his close search. Money there was none; and the goldsmith felt, with increased alarm, that this was another link in the strong chain of presumptions which was about to fetter him. The usurer’s gains of the day were, no doubt, known to many individuals in the city; and if (as he had understood the dying man to intimate), these had been already mingled with the mass of his treasures, where was any evidence to rebut the suspicion which would inevitably connect their disappearance from his person with the murder?

In a state of now fully-awakened apprehension, the unfortunate goldsmith threw himself on his bed; and collected his thoughts for a decision on the course which, under the circumstances, it might be safest for him to pursue. He had much of the long dark night before him; but, on the morrow, to denounce the murder to the authorities was, he felt well assured, of necessity to give himself into their hands—without, as far as he could see, the possibility of furnishing any testimony by which he could rescue himself from the jealousy of the law. What, then, was the alternative? There was but one,—a very dangerous one,—certain to furnish irresistibly corroborative evidence against him, if discovered; and that was, the concealment of the body and suppression of the facts.

As, however, he continued to reflect upon this alternative, his fears began gradually to subside. There was not a single circumstance to connect the disappearance of the usurer with Ricciardo or his home. No one had seen the usurer enter his house; no cry had been heard; no blood had been shed; and the alchymist had been conspicuously at work, far into the night, with his glowing furnace and his open door. It was, as it seemed to him, his single chance against the gallows. His fearful state of uncertainty and apprehension gave way before its contemplation; and, as his resolve was finally taken, the miser’s keys, which he still held, were tightened in his grasp. Suddenly, the spasm of a moment shook his frame—the dew stood on his forehead,—and his breathing came hard and thick. A thought had passed into the goldsmith’s mind, which sent the blood tumultuously to his heart. It presented itself, in the first instance, in the shape of a mere vague and formless suggestion; but the breast of the alchymist was one well fitted for its reception and nourishment,—and slowly and steadily it took shape and lineament. Here were the keys which gave access to the miser’s treasure!—Such was its first shadowy aspect; but the goldsmith kept it steadily in view, and set his mind to work it into a form agreeable to his own imagination. The usurer was gone,—his death was unknown,—his absence would be, for some time, unsuspected—his gold was ownerless,—and Ricciardo held the talisman which made it his. The dead man had neither relative nor friend, so far as was known; his wealth must pass into stranger-hands, and why not into Ricciardo’s, rather than any other? Nay, he even persuaded himself that he had a better right than others, in virtue of the attentions which he had bestowed upon the wounded man, and his ministration at the deathbed of the miser. Was he not, perforce, the dead man’s executor, about to render him the rite of burial?—and did not the friendless usurer’s selection of his house for that closing scene and those final offices, properly constitute him his heir? Step by step, he brought himself to look upon it as a natural consequence of the position in which he found himself, and a fitting corollary to his scheme for the concealment of the body, that he should possess himself of the wealth so strangely offered to him in his very hour of need; and, in the spirit of transmutation for which he had so much taste, he felt that he had a title to change into his own benefit the heavy danger with which he had been thus innocently threatened.

The more the alchymist reflected on the matter, the more arguments did he find in favour of the view which he had adopted; and the longer his mind dwelt upon the riches thus presented to his disposal, the better and more conclusive each of those arguments seemed to become. In the strong excitement to which his spirit was delivered, all the occult mysticism of his nature was brought out. The dreams which had presented his beggared family and the miser’s gold, as in a common speculum, recurred to him, taking the character of a positive direction; and that singular coincidence which he had already remarked in the events of the night, now suggested itself with redoubled and irresistible meaning. The death of the rich miser, at the very instant when, engaged in the occupations of humanity, the alchymist had suffered the grand arcanum to escape him—at the very moment of projection—appeared to him an evident substitution, in which he must be morally blind not to recognise the direct interference of heaven. His imagination strengthened marvellously upon the nourishment with which he supplied it; and, in the calenture of his brain, he brought himself at last to see, in all the incidents of the night—in the storm—in the massacre of Grimaldi itself—in the fact of his own shop alone having been open, in all the street—and in that of the usurer transporting his wounded body thither to die, at the precise hour when the secret of his fortunes was to be solved—so many obvious parts of a providential scheme to crown his long cabalistic labours with success. His mind was in far too mystical a state to recognise how little his alembics and crucibles had had to do with the matter—and how surely the events which were about to lead him to fortune would have happened, in their order, without the aid of any of his alchymic preparations—save only the furnace, whose light had directed the wounded miser to his door. Neither was he in a condition to perceive that, in all his former experiments for the attainment of gold, the one ingredient in his combinations which had been wanting to their success, was precisely that on which he had stumbled, by accident, on the present occasion,—to wit, a rich old usurer, with a poniard in his pectoral artery. It is, however, scarcely to be wondered at that the necessity under which the goldsmith found himself, as the reward of his humanity, to conceal the old man’s death, lest he should pay the penalty of murder, added weight to the many arguments which combined to convince him that he was the subject of a fatality, which distinctly pointed him out as the usurer’s heir. His determination was therefore (and, finally, without any misgiving), taken; and, as the night was wearing onward, and there was much to do, no time was now to be lost in putting that determination into execution.

Providing himself therefore with a lantern, and the means of lighting it when he should arrive at his destination, the alchymist secured the ponderous keys in the folds of his cloak; and having carefully extinguished the light within his dwelling, and securely fastened his door, he groped his way, through the darkness and tempest, to the miser’s deserted abode. The storm had burst forth with renewed fury, as he left his home; and the aid which this circumstance contributed to the silence and secrecy of his expedition, was, in the excited state of his spirit, hailed as a further token of providential acquiescence in its object.

Arrived at the usurer’s door, he found ready entrance by means of two of the larger keys which he had taken from the body; and stepping hastily across its threshold, stood within the naked walls of that lonely dwelling, which no stranger-step but his own had entered, since the day when its late occupant took up his abode therein. For an instant, his heart sank beneath the sense of so heavy a profanation; and his imagination conjured up the ghastly miser, to meet him at the entrance and dispute his passage. The moments were however too precious, and he was too firmly nerved in the belief of a cabalistic guidance, to give way to such visionary presentiment. Carefully, therefore, securing the door which opened from the street, he lighted his lantern, and proceeded to an examination of the mysterious premises, and a search after their rumoured treasures.

In a corner of the wall which faced this outer door, a second door of great strength presented itself, crossed by bars of iron, and secured by many locks of different sizes. After some difficulty in the selection of the various keys which governed these locks, the goldsmith succeeded in mastering this obstacle to his progress; and obtained access to an inner-chamber, which had apparently been the sleeping-room of the unhappy usurer. The window which had once given light to this apartment was now built up; and the miserable pallet which had witnessed the uneasy slumbers of the anxious wretch, a small table, a single chair, and two or three strong chests,—ostentatiously left open, and containing merely some articles of ragged apparel,—formed the whole of its visible furniture. There was no second chair in either apartment, and they had evidently never been designed to receive a guest. But what was of more importance to the goldsmith, and not a little perplexing, was the entire absence of any visible evidences of that wealth which fame had accumulated in the usurer’s abode. The room exhibited neither coffer nor closet, which might offer itself as the guardian of the treasures which he sought. The goldsmith, however, was too confident in the destiny which had led him thither, and had far too much at stake, to be turned from his purpose by a difficulty which was, of course, but an effect of the miser’s abundant caution. After a careful examination of the floor, and of the walls on those three of their sides which were wholly naked, he proceeded to an inspection of that end of the apartment which was occupied by the usurer’s bed; and found that, unlike the other walls of the chamber, the one in question was of wainscot, and handsomely worked in square panels.5Wainscot is an area of wooden paneling on the lower walls of a house. Drawing forward the miserable pallet, whose tattered curtain concealed a part of this wall, he sounded the whole of it with his knuckles; and found, as he had expected, and to his great satisfaction, that a portion of it which covered three panels in breadth and four in height, returned a hollow sound to his blows. Here then was the miser’s treasury!—and how to obtain access to it was now the only secret betwixt him and wealth. The panels presented neither seam nor perforation, and were alike to the eye; save that, on a more careful inspection, one of the centre squares appeared to the goldsmith to recede from its projecting framework rather further than the others. To this square, therefore, he directed his attention, though without success in his attempts to make it slide in any direction; but pressing its frame on all sides, he felt the upper wood suddenly yield to his touch, and the panel fell down behind that which was immediately below it with a sound which made his heart leap,—revealing the mystery of the usurer’s concealment, and opening up the penetralia in which he had placed his god. The alchymist now perceived that the wall on this side had been built forward into the chamber, to the depth of two feet beyond its original boundary,—leaving a space in the centre, into which was fitted an iron safe of considerable height; and the whole was then covered with panelled wainscoting, the falling square of which answered to the iron door of the concealed coffer, and was covered by the curtain which fell at the head of the miser’s bed. The coffer itself was fastened by many locks,—which, however, were readily opened by the remaining keys in the goldsmith’s hand; and the wealth of the usurer stood at length displayed, by the light of the lantern which Ricciardo cautiously introduced into its mysterious shrine.

If the alchymist was an enthusiastic man, he proved himself to be, on the present occasion, under circumstances of strong temptation, also a very prudent one. The riches of the usurer presented themselves under various dazzling forms, which it must have cost an alchymist considerable efforts of self-denial to resist. There were golden rings and bracelets, diamonds and other precious stones; and, amongst a quantity of loose coins of different descriptions, four sealed bags, each of which had been marked by the usurer as containing five thousand golden crowns. It was, of course, the goldsmith’s policy (since he was calm enough, in the midst of his mysticism, to be politic at all), that no reason should be found for suspecting theft, when the premises of the missing man should, at length, be ransacked by the authorities. To remove the whole of this property,—and, in fact, not to leave a large portion of it untouched,—was at once to announce a robbery. The jewels were of less ready and safe conversion to the alchymist’s purposes than the gold, and courageously, therefore, rejecting treasures, a tithe of which were well worth all his chances of the grand arcanum, he resolved to content himself with removing the sealed bags, trusting implicitly to the usurer’s statement for the fidelity of their count. Then, locking the richly-furnished coffer, closing the panel, and replacing the bed, he returned with his booty to the outer apartment; and, having carefully restored the bars and locks of the massive inner-door, and extinguished his lantern, he quitted the mansion of the miser, made fast its outer entrance, and gained his home unseen and without interruption.

The night was now far advanced; and, carefully securing his doors, he set about the performance of his remaining task. Lifting the body of the usurer from the couch on which it lay, he descended to his cellar; and having removed the bricks which floored it, for a sufficient space, proceeded to dig a grave, as deep as the time yet at his disposal permitted. Then, having restored the keys to the pocket of the dead man, and deposited him in the ground, in his garments as he died, he replaced the earth and bricks, carefully obliterating the traces of recent disturbance; and stealing up to his chamber in the grey dawn of the morning, flung himself on his bed, satisfied with his own solution of the great secret,—and, worn out with fatigue and emotion, slept the long and dreamless sleep of the utterly exhausted.

The day was far advanced when the alchymist awoke, refreshed and invigorated, and applied his renewed powers to the consideration and arrangement of the further conduct which he had yet to pursue. Great caution was, of course, necessary, in the production of his suddenly-acquired wealth; and, for the present, he determined to make no change in his apparent circumstances or pursuits. The prolonged absence of Grimaldi began, after some days, to excite speculation, and finally alarm; and his gates were, at length, forced by the order, and in the presence, of the magistrates. As neither the usurer nor his treasures were found, the city seal was put upon his doors, to await his return; and when a period of some weeks had destroyed that expectation, it was considered necessary to make a more strict perquisition into the affair, and a more minute examination of his late dwelling. The result was, that his hoards were discovered, to all appearance untouched, and taken possession of by the authorities; and his strange disappearance, after being the subject of marvel and conjecture, throughout the city, for some weeks longer, began at length to lose its interest, with its novelty, and, finally, was forgotten, in matters of higher or more immediate attraction.

It was not until the minds of his neighbours had ceased to be occupied with this affair, that the goldsmith began to utter vague hints, which soon became rumours, of his discoveries in alchymy. By degrees he ventured even to speak of golden bars which were the product of his mystic labours; and though his wild assertions were laughed at by the many, who knew how often the enthusiastic alchymist had been the dupe of his own imagination, yet they were sufficiently in harmony with the spirit of the age to make believers of some, and attract the curiosity of more. By degrees, the tone of the goldsmith became more bold and decided; and at length, he openly announced his intended departure for France, to exhibit his ingots to the princes who, in that country, were speculators for the philosopher’s stone, and to change them for gold of the currency. For the purpose of reconciling the necessary cost of such voyage with the supposed state of his finances, he contrived to borrow a hundred florins for his expedition, on the strength of his grand secret, from one of the numerous waiters upon fortune who, in those days, were willing to risk something for the chance of a share in the profits of the patent for making gold.6A florin was a British coin. Of this sum, he confided one half to his wife for the maintenance of herself and his children, during his absence,—and with the remainder he prepared to depart on his promising journey.

It has been already said that Ricciardo had wedded, in early life, the object of a passionate attachment; and neither the years which had passed over them since their bridal day, nor the anxieties and struggles by which those years had been marked, had brought any change to that fond attachment, or any chill to the deep devotion with which it was repaid. For the sake of the beloved of his youth, and of the children whom she had borne to him, it was that the alchymist’s search after gold, which had once been only a taste, had become an engrossing passion. For them, chiefly, it was that he coveted that splendour, with the dreams of which his visionary spirit had fed him so long and so dangerously. To Beatrice, her husband had been the subject of many a care and many a fear,—on which her love had, nevertheless, but grown and strengthened more and more, as on its most appropriate food. The exaltation of his nature, the long and lonely vigils to which it led, and the sacrifice of his time, and what little property he possessed, to his fantastic pursuits, had been sources of deep anxiety to his less sanguine wife; and she had, more than once, trembled for the probable effects of what she feared were his delusions, upon his highly-excitable brain. If he had, at one time, succeeded in inspiring her with a portion of those hopes which nourished his own imagination, they had long since yielded, in her heart, before repeated disappointments and the gloomy aspect of their yearly darkening fortunes. On the present occasion, the resolution of the alchymist,—which was to take him, for the first time, (under the influence, as she believed, of a heated and deceived imagination), far from her fond superintendence, and deliver him into the hands of strangers,—was, to her, a subject of deep distress. Every argument was used to which his undoubted affection for her might give force, to win him from his purpose; and tears and fond reproaches (those weapons which woman, when she is beloved, wields, with such unfailing effect), were resorted to, when all others had proved unavailing. The kind nature of the goldsmith was easily moved, at any time, by the aspect of distress,—and against the tears of his wife it had no chance of a prolonged resistance. Unable, therefore, to reawaken her faith in the success of his alchymic projects, and mastered by her grief, he persuaded himself, at length, to the only other course which was capable of reconciling her fears with the prosecution of his scheme. Leading her into his cellar, and standing on the usurer’s grave, he confided to her the secret of his wealth, and succeeded in removing her scepticism as to the reality and value of his gold.

Whatever womanly fears it was natural that Beatrice should experience, at the doubtful circumstances in which her husband had been innocently placed,—she was, however, perfectly satisfied with the uses that had been extracted from them, and greatly disposed to adopt the alchymist’s opinion of the special intentions of Providence in his favour, with a view to which the assassination of the usurer, amongst other things, had, as he argued, been permitted. It was necessary, however, that she should continue to play the part of a reluctant and afflicted wife; and accordingly, the goldsmith left his home, amid her tears and remonstrances, laughed at by half the city, and quietly laughing in his turn, and in his sleeve, at the whole.

On his arrival at Marseilles, the alchymist immediately proceeded to convert his gold into letters of exchange, upon substantial bankers at Pisa; and, after the lapse of what he deemed a sufficient time, he wrote to his wife, informing her that he had sold his ingots, and was about to return home with the produce. This letter was triumphantly shewn, by Beatrice, to her relatives, her friends, her neighbours;—to every body, in short, who chose to look at it,—and created no little amazement. The ingots, it was therein stated, had been pronounced to be of the purest metal; and the news of the grand arcanum having been realised spread through the city, with wonderful celerity. The lovers of the marvellous, the followers of science, and the greedy after gold, were alike interested in the intelligence. All the crucibles in the city were once more brought into action,—all the illuminati set in motion; and when the great alchymist returned to Pisa, and made his extensive deposits with the bankers of that gaping town, he, who had left with the reputation of a fool, came back with that of a sage, and was received with all the honours due, at once, to sublimated science and substantial wealth. The character and temper of the man were calculated to ensure him the esteem of those with whom these circumstances brought him into association; and the once poor goldsmith of Pisa, lived amongst his fellow-citizens, exciting no jealousy by his amended lot,—winning the love of many, and yearly rising in the estimation of all.

But, if the fortunes of the alchymist had come out brilliant and golden from the labours of his youth, his disposition had, in some respects, undergone a transmutation, which was not into the more precious qualities; and his ardent and passionate nature was, now, to be exposed to the peril of fulfilled desires. That sickness of the heart which ariseth from hope deferred had been too suddenly removed; and, like the physical convalescent, when first he leaves the chamber of lingering sickness, it seemed to him that he could not drink too large draughts of the bright sunshine and perfumed air into which he had issued. The more animal parts of his nature, which had been kept down by his deep poverty and transcendental pursuits, awoke, at the many voices which called upon them, amidst the new scenes in which he was placed; and his passions, nourished into force by the strong stimulants on which he had fed them so long, were now directed into paths more dangerous, and less pure, than those in which they had formerly walked. The rich and luxurious of those days, in Pisa, appear to have lived pretty much after the same fashion, and cultivated pretty nearly the same vices, as the parallel classes of London and Paris, do in our own; and the alchymist, suddenly released from the painful restraints which had made his youth one of suffering and privation, and admitted within the sanctuaries of those privileged vices, responded too readily to the novel temptations by which he was surrounded. Not that the goldsmith’s heart (which, having little occupation in scenes like these, went to sleep, for a period), was reached by the pollutions of the world. But his head,—which had, at all times asserted its ascendancy, and carried him whithersoever it would, now ran away with him, amidst the unaccustomed tumult of the new path on which it found itself, and delivered him over to the dissipations which there assailed him. The wife of his youth, who with her children, had, in the day of his adversity, been the sole objects of his hopes and wishes, now found that their empire (if not over his heart, at least over his imagination), was divided by many another claim; and Beatrice began almost to regret the anxious days of their young loves, and the wild, and as yet unrealised dreams of alchymy.

Amongst the many who partook of the bounty which flowed freely from the kind goldsmith’s altered fortunes, was an orphan girl, who was distantly related to his wife, and whom, at her request, he had introduced into his establishment. Unhappily for Ricciardo, Irene was surpassingly beautiful,—and more unhappily still, she was very conscious of that fact, and very much of a coquette.7A flirt. Long ere the goldsmith was aware of his danger, he had already drunk large draughts of love, from the eyes of the orphan girl; and long ere his wife was startled from her fond security in his faith, he had, in the intoxication thereby produced, revealed his passion to its object, and won her to its return. In the delirium of his feelings, the goldsmith was far too little master of himself for their long concealment; and when, at length, the withering truth burst upon Beatrice, it was received by her as the lightning might, which should have scorched her without destroying. Long years of evil had Beatrice borne,—and all evil she was prepared to bear, for the husband of her heart, save this evil alone. The love of that husband was a treasure with which she had once consoled herself for the absence of every other; and she was not now, disposed to barter it against the murdered usurer’s gold, or all that it could buy. Her apparently calm and gentle spirit had in it a spark of that fire, which had, probably, been communicated to it from the alchymist’s own; and the blow which was now struck against her heart revealed it, at once. In its first eruption, Irene was driven from her protector’s home, with passionate reproaches; and Ricciardo compelled, for a moment, to shrink before the indignant appeals of his outraged wife.

But the alchymist was too completely under the mastery of his passion to yield final obedience to the impassioned pleadings of her whose lightest wish had anciently been his strong law; and his better nature was so far darkened by the madness which possessed him, as to suffer him to answer her agonised remonstrances by the bold avowal of his unworthy flame. Like the maniac which a guilty passion had made him, he trampled, in very wantonness, on the heart which he had guarded so fondly and so long; and, reckless, alike of the wrong which he did, and the anguish which he inflicted; deaf, to all suggestions save those of the fever which enthralled him,—ultimately quitted his home, with the declared purpose of procuring another for Irene, —and sharing it with her.

The struggle was a fearful one to which the spirit of Beatrice was delivered, when she was left alone; and it was long ere her anguish took that gentler tone which yielded the relief of tears. In that softened mood, the memory of their early loves rose up, with a sweetness which made the memory of their early poverty sweet. Again and again, did she curse the gold which had won them from the calm security of their humble and almost desperate lot; and freely would she have paid it all away, to be again the anxious and lonely thing she was, in those days,—if thereby she might buy back the love which had made even that loneliness and that anxiety most dear. Amid the alternating paroxysms of her fiercer feelings, she was still haunted by this one thought; till, in the wildness of her mood, and with something like her ancient tendency to cabalistic belief, she came to look upon that gold as, in itself, the actual spell by which her husband was held,—and to fancy that to dispossess him of his wealth would be to disenchant him. Her heart clung, eagerly and dangerously, to this imagination,—which her unsettled reason was not competent to correct; and, mad with the thought of her wrongs—and groping, amid the darkness of her mind, after a visionary and fantastic redress—she went wildly forth from her deserted home, and, in her jealous frenzy, denounced her guilty lord to the authorities of Pisa, as having built his fortunes on the robbery of the usurer’s gold.

Great was the sensation excited by such an accusation, against such a man, and coming from such a quarter. No time was, however, lost, in verifying the facts. The story which had been told by Ricciardo, about the usurer’s grave, was taken down from the lips of his distracted wife: the cellar of his ancient abode was dug up, and the body found: and the goldsmith was dragged from the arms of Irene, to exchange the visions of a guilty passion for such dreams as might visit his solitude, in the dungeons of Pisa.

When Beatrice returned to the home which she had made for ever desolate, she found it in possession of the officers of justice; and, in reply to her incoherent questionings, she learnt, from their rough lips, that her husband was the occupant of a prison. Her frenzy gave instant way, before the pang which shot through her spirit; and, with the clearness of despair, she saw, at once, the fearful significance of that which she done. Mad no longer—but like one mad—she rushed from the house, and retraced her steps to the magistrates. But it was too late. No tears nor prayers could avail, now, to cancel that which had been done. The words were gone forth which could never be recalled.8Original “berecalled.” Vain was her passionate retractation of all to which she had deposed;—vain were her protestations of insanity, at the moment,—her admissions of jealousy and revenge,—and her wild assertions, that she had but sought, by a fictitious tale, to take from her husband the wealth which ministered to his estrangement, and win him back, a beggar, to her arms. The story told by her had furnished the key to many things which formerly seemed strange. The sudden disappearance of the miser, and the sudden enrichment of the goldsmith were alike explained. It was remembered, too, that some surprise had been felt, when the miser’s treasures were discovered, at the small quantity of coin which they included—and some curiosity excited, in consequence, as to the manner in which the rapid and constant conversion of his wealth into jewels could have been effected. The body, too, had been found, and identified; and no doubt whatever existed that Ricciardo was, at once, a robber and a murderer! The question of the miser’s disappearance cleared up, by the verification of his death—and the absence of all other claimants—authorised the disposal of his treasures to the purposes of the state: and the trial of the goldsmith was, for all these reasons, hastened forward, amidst the mingled horror and regrets of the entire city.

Alone in his dungeon—and in the contemplation of that fate which he knew that nothing could avert—the spirit of the goldsmith righted itself. Rebuked by the place and circumstances, his passions abdicated, and his purer nature regained the ascendant. His heart awoke from the deep slumber into which it had been cast, by the narcotic of lawless love; and his mind, at the same time, shook off the delusions by which it had been so long held in thrall, and came clear out of the mists and shadows which had darkened it, through the greater number of his days. He saw distinctly through the mysticism which he had nourished, till it had made him its victim; and knew, at last, that he was unquestionably, before men—and before that God whom he had claimed for an accomplice—a robber! He saw, too, that the very vices which his ill-gotten wealth had fostered, had led directly to the exposure of the evil source from whence that wealth had been derived,—that the mystery of his fate was explained, and its moral complete. To that part of the charges against him which fixed him with the stain of robbery, he answered by a calm and mournful avowal; but resolutely persisted in flinging from him the accusation of murder. It was in vain, however, that he detailed the circumstances of that eventful night when the usurer came, wounded, to his door; and in vain he, too surely, felt that it must necessarily be. The facts were too strong against him. Still, he bore the torture with a resolution that faltered not, in this respect: till, wearied out by his firmness, pitying his pangs, and having evidence enough of his guilt to justify his capital condemnation, his judge sentenced him to die—and he was left, at length, alone, to prepare for his final scene.

And now, at this last hour, when the strange wild riddle of his life was solved, and there remained for him but to die, stole back to his heart—as they almost always do, at such a time— the sweet and wholesome memories of his youth; and with them came the image of his first and pure and happy love. With the passing away of the false and feverish passion which had misled him, all angry feelings had, likewise, passed away. It was too true that the wife of his bosom (and now, again, of his undivided affection) was she who had conducted him to the scaffold; but it was in a moment of madness caught from him—and for the love of him. She was, in truth,—as she had ever been, from her childhood upwards, dragged onward and involved by his own dark destiny,—as much its victim as himself; and his spirit yearned to clasp her again, before its final divorce. It was a boon readily granted. The requisitions of justice were about to be sternly satisfied; and the magistrates felt that they might be merciful. That last night Ricciardo and Beatrice passed together; and, clasped in each other’s arms, went back again over all their little history of the heart. Like all their strange life, there was something strange in that final scene of it which they were to enact together. The canvas of their long and fitful story seemed, as it were, spread out, anew, before their mental vision. No cloud, either of grief or guilt, remained in the clear breast of the morally emancipated goldsmith; and Beatrice, in the restoration, at this final hour, of her husband’s love, and the renewal of that fond confidence which had made the charm of her existence, fancied, for awhile, that happiness had come back, and forgot the heavy price which remained to be paid. They spoke nothing of the present—as a matter in which they had no further concern; but went wandering, wandering back, over the long past. It was as if the history of their lives were already closed, and they were reviewing it. The moon looked in upon them, like an old friend, through the prison-bars, as they talked of their early loves—of the fields in which they had wandered, long ago—and the starry nights which had heard their young vows. And when the morning dawned, and the alchymist (an alchymist no more),—after one long, long glance, and one lingering kiss, so softly given that it might not awake her,—went silently and calmly forth to his eternal rest, —he left the companion of all his days under the shelter (from that dreadful moment) of a deep and peaceful sleep!

———

The Chronicles of Pisa give hints of a fearful catastrophe, with which we feel most reluctant to darken the close of our tale. Awakened from her slumber, and driven into irremediable madness by the awful significance of the solitude in which she found herself, the wretched wife is said, by them, to have made her way through the streets of the city, with her children in her arms, and amid the execrations of the crowd, (which, however, she understood not), right to the scaffold. There, having ascended, on the pretext of embracing the body of her husband, and hung the little arms of her children about their dead father’s neck, amid the passionate sobs to which the anger of the multitude had given place, at the spectacle, she suddenly struck a poniard to the breast of each; and, ere the officers who stood at the foot of the scaffold could interfere, had succeeded in guiding the bloody weapon to her own heart.

T. K. Hervey

Word Count: 8769

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Jarom Cluff

Rachel Jones

Elizabeth Etherington

Posted

5 March 2025

Last modified

21 April 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | A tragic play by Henry Hart Milman about a man whose love for his wife’s sister leads to disaster. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A poniard is a small dagger. |

| ↑3 | In the original, the em-dash is made up of three hyphens. All of the following em-dashes will be corrected accordingly. |

| ↑4 | Rosicrucianism is a European spiritual movement involving mastering one’s life and living in harmony with the world. |

| ↑5 | Wainscot is an area of wooden paneling on the lower walls of a house. |

| ↑6 | A florin was a British coin. |

| ↑7 | A flirt. |

| ↑8 | Original “berecalled.” |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.