The Music of a Violin

The Quiver, vol. 30, issue 358 (1895)

Pages 745-748

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Music of a Violin” tells the story of young prodigy Paul Fürstner, who struggles with the demands of his mentor and the music industry. His rise to public prestige is exciting and invigorating to his mentor. However, through Paul’s tragic decline, author Nellie K. Blissett carefully critiques and ultimately raises questions about exploitation and ethics within society.

Advisory Note: This story contains a reference to child abuse.

“I hear the sound of death upon the harp.”1Reference to The Poems of Ossian translated by Scottish poet James Macpherson, published 1760-1765.

Ossian: Dar-thula

It was a small upper room in a London house. There were dingy blinds across the windows, and two or three indifferent pictures on the walls, and the furniture was neither new nor bright. In one corner was a small iron bedstead, and a round table filled up the centre of the space between the wash-hand stand and the window.

At the table a boy was sitting, bending down over a sheet of music paper; his face was hidden in the position in which he leaned against the hard wooden edge, but the light fell on his fair hair and rested there. At his left hand lay a violin and bow: at his right was a pile of music.

A sparrow flew past the window, and the boy sighed and moved wearily, turning his face towards the light. It was a flat, ordinary-looking face enough, but for the eyes, which were large and luminous, with a peculiar distant expression, as though fixed on some unseen object. The child could not have been more than eight at most—possibly he was even younger. He rose slowly and pushed his chair back from the table.

As he stood thus, the door opened abruptly and a man came in. He took up the sheet of music-paper, and skimmed over it with the practised eye of one who could detect a mistake at a glance.

“It is all right,” he said, looking up from the paper. “I should not have doubled that sixth if I had been you—it sounds awkward. But we will talk of that presently. Geltmann is in the drawing-room; he wishes to see you. Bring your violin.”

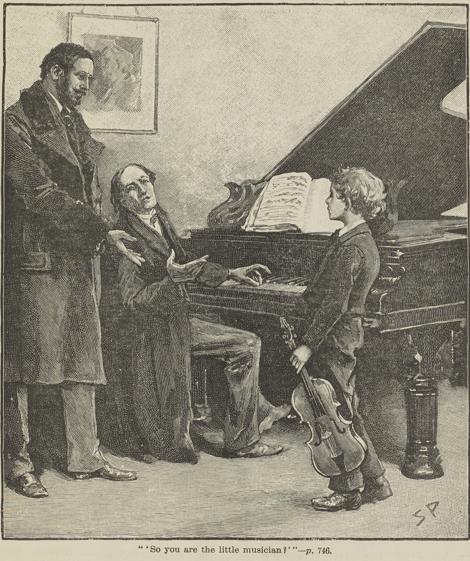

Geltmann turned sharply as the boy entered the room, and held out his hand, smiling. His smile was very pleasant, and when he spoke it was with a strong German accent. His English was quite different from the Professor’s; it was more marked, and much harsher. The Professor spoke smoothly and quietly, with only a little hitch now and then.

“So you are the little musician?” said Geltmann. “Well, I hope we shall be great friends—eh, Professor? You must come and see my boys—when you have time. We mustn’t interfere with the music, must we?”

“No, mein Herr,” said Paul, feeling a strong disposition to answer in his native tongue. But the Professor always insisted on his speaking either English or French, and he never disobeyed him. It had never occurred to him that such a thing were possible.

The Concert-Director glanced at the boy curiously; the grave, quiet manner rather puzzled him.

“You had better get in tune,” interposed the Professor, striking the A. “Mr. Geltmann wishes to hear you play.”

“If he is quite inclined.”

The Professor made a little quick movement of impatience.

“Oh, he is always inclined—Sharper, Paul—can’t you hear? That is right.”

The Concert-Director moved away rather uneasily; it is doubtful if he understood the Professor. Few people could pride themselves on that achievement.

Paul Fürstner was the Professor’s protégé—his pet pupil. The child’s talent had attracted his attention, and he had persuaded the German peasant-woman—a widow, with six other children,—to part with her boy that he might become a great violinist. I do not know the Professor’s recipe for making great violinists, or I might benefit personally by it; but it was a remarkably rapid process. He had succeeded in making the child of eight a master of his instrument, and he had kept his word. The great violinist was there—now he was to be made public property.

Geltmann sat and listened with an interested face while Paul played, the Professor accompanying him. They played several things—I forget the names now, though Geltmann did tell me at the time.

The Concert-Director did not say much. When they finished, Paul was dismissed, and the professor began to talk of other things. Presently Geltmann rose to go.

“Well,” said the Professor, returning suddenly to the object of his friend’s visit, “what about Paul? Will you bring him out?”

Geltmann paused and hesitated, then replied, “I have two prodigy-pianists to bring out this season.”

“These children!” shrugged the Professor irritably.

“Paul is a child too,” said the Concert-Director; “you forget, Professor. But had he not better wait?”

“He is fit to come out—a great deal more fit than half the fools that do. Why should he wait?”

The Concert-Director avoided a direct answer.

“I will see about it,” he remarked, evasively.

“There is time yet, you know. By the way, Professor—is the boy strong?”

“Well, if he isn’t? What has that to do with his coming out?”

“He is only a little chap,” said the Concert-Director, “and you know it is hard work, studying for concerts, Professor. And then the excitement and worry of the thing itself—”

“Oh, I will see about that,” interposed the Professor crossly. “You needn’t take it up unless you like. There are plenty of agents who will be only too delighted to introduce him.”

The Concert-Director sighed. “All right, Professor—I will bring the boy out. Only, if he breaks down, don’t blame me.”

“He shall not break down,” snapped the Professor.

“Poor little chap!” said Geltmann, as he went away.

* * * * *

That evening I went around to see Marciera. Sveczalski was with him, and they were discussing the Professor and his pupil. Marciera, it appeared, had heard Paul Fürstner.

“His playing is very wonderful,” he said thoughtfully. “For a child of his age it is marvellous. But somehow this prodigy business strikes me as being unnatural.”

“I should not have thought the Professor would go in for the prodigy business, as you call it,” I said.

“No. He generally sneers at it. But then there is nothing he does not sneer at when he is in a bad temper. It is not safe to trust the Professor’s impressions of the Universe. They are generally taken from the darkest point of view possible.”

“I wasn’t a prodigy, and no more were you,” said Sveczalski, “so perhaps we shouldn’t talk.”

“If I had played like that boy at his age, I should have been worn out by now,” replied Marciera. “You can see that every nerve in the child’s body is quivering with excitement—I don’t like it. What do you think, Bazarac?”

“I don’t know what to think. It seems strange to me from a purely technical point of view, that a child can play like that. But if you two geniuses don’t understand it, how should I?”

“It isn’t a question of genius,” said Sigmund.

“For that matter, I suppose the Professor is a genius, too.”

“That is exactly what he isn’t”, said Marciera, very quickly. “He has everything else—technique—elegance, very much of it—and expression, of a sort. But he has not got genius. And this child—well, it is overly-early to judge, but I should say he has genius, and it has been developed much too soon. It isn’t natural. And the Professor—he calls me a charlatan because I can play harmonics better than he can; but it seems to me that this is a much worse form of charlatanism—for it is injuring an innocent object. At least, he cannot say that my harmonics injure anyone.

“How do you know that there is any injury in the matter?” asked Sveczalski, curiously.

“I do know,” said the Spaniard briefly.

* * * * *

So Paul Fürstner came out. A great fuss was made over him, and a great many flaring bills paraded the streets. I did not go to his concert, but the rest of London did—and applauded. He was such a success that he gave another recital soon after the first. Presently there came another.

And when the third recital was announced, Marciera looked very black. We happened to be passing Geltmann’s Concert-Agency, and he dragged me in and asked for the Director.

“When is that wretched child’s next recital?” he asked.

“On the 10th,” said Geltmann.

“Exactly a week after the last. Do you know what you are doing?”

“Really, Marciera—” began poor Geltmann.

“You are killing that child,” and Marciera glared at him.

“My dear Marciera,” said Geltmann, in despair, “what do you mean? The Professor—”

“The Professor is a fool!”

“I only wish he were,” sighed Geltmann. “I don’t want the recital to take place. But the public run after the boy so—”

“Exactly,” said Marciera grimly. “To succeed in these days, one must be either seven or seventy. Quite so. Good-morning, Geltmann,” and he marched off.

* * * * *

The third recital came off in due course. There was an enthusiastic audience, and several encores were exacted from the poor little concert-giver. Large bouquets were handed to him, and he was called back again and again to bow his acknowledgements. But it came to an end at last, and the Professor carried his pupil home.

He noticed, as the boy followed him into the house, that he looked pale and moved wearily.

“You are tired, Paul,” he said suddenly. “Go to bed, and I will send you up some tea. What is the matter? Does your head ache?”

“A little, Professor.”

“I thought so. Go to bed.”

Paul went. When the professor took him up his tea, he was fast asleep.

“I shall not wake him,” said the Professor, as he went noiselessly out of the room.

The child never woke up that night; he slept on, a restless, troubled sleep, haunted by the wild visions that vex an overtaxed brain. Bouquets and double-bars seemed to float before him, and the sound of his own violin was always in his ears. He could not escape from it.

“He is only tired out,” said the Professor to himself.

Truth to tell, there was a very ugly foreboding in the Professor’s mind. He was not by nature cruel, and the child’s pale face worried him. His own sleep was broken that night. But the next morning, after the Professor’s first visit to Paul’s room, he came out looking very strange.

For the child was delirious. He was talking wildly of staccato passages, and harmonics, and double-stopping. The Professor was frightened for the first time in his life, and sent for a doctor. The doctor came, looked very grave, and said very little. When he left, the Professor, in despair, telegraphed for Geltmann.

The Concert-Director threw over all his business when he got the telegram, and started for the Professor’s house as fast as he could go. When he got there he was shocked at the violinist’s anxiety.

“He is very ill, Geltmann,” said the Professor. His face looked haggard, and he spoke like a man crushed down by a great fear.

“What does the doctor say?”

“I don’t know. Nothing much. Geltmann, he is dying—I know he is”—and the Professor laid his hand on the other’s arm helplessly.

“Don’t despair,” said Geltmann kindly. “He may get well.”

“He is dying,” said the Professor again, in a choked voice; then he led the way to Paul’s room.

It was a pathetic scene enough in the little room, with its dingy windows. The violin-case lay on the table, and beside it, in a glass of water, stood a magnificent bouquet, filling the air around with its perfume. And the sick child, lying in the small bed in the corner, was talking deliriously in broken, disconnected sentences—always of his profession. Now he was practising with the Professor, now he was at a recital, now he was submitting some composition to the Professor’s criticism. Geltmann’s eyes filled with tears as he listened; it seemed to him that all the tragedies he had ever seen were not half so sad as this. He thought of Marciera’s ominous words, and shuddered; in his own heart he knew the Professor was right. Paul was dying.

The Professor was clearly in no state to be left with his own reflections. Geltmann took up his abode with him for the time being, and let all the rest go.

Day after day, and night after night, the kindhearted Concert-Director sat and listened patiently to the child’s ravings, or the Professor’s dismal forebodings. Paul never knew him, nor the Professor either. The doctors held out no hope; the child would either die or be insane for the rest of his life.

Geltmann heard the verdict in silence; he did not dare to look at the Professor.

That day, at sunset, as the Concert-Director sat alone in Paul’s room, he heard his name spoken faintly. Paul was looking at him with an expression of recognition in his eyes.

Geltmann went to the bedside quickly.

“What is it?” he asked.

The child did not answer a’ once.

“Did I play well?” he whispered presently.

“Yes, my boy,” said Geltmann.

A bright smile broke over Paul’s face. He lay silent for a little while. The room was intensely still, and the last rays of sunlight fell through the window on to the foot of the bed.

“Will you write and tell them—at home—that I—played well?” he said suddenly.

“Yes, my boy,” said the Concert-Director once more.

There was silence again; then, in the stillness, there came a sound from the violin-case on the table.

It appeared to rouse the child: he looked up.

“A string has broken,” he said, in a clear, strong voice.

* * * * *

And for him, too, a string had broken—the silver string of Life.

Word Count: 2925

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Alissa Merrill

Elizabeth Goss

Kayla Williams

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

5 March 2025

Last modified

3 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Reference to The Poems of Ossian translated by Scottish poet James Macpherson, published 1760-1765. |

|---|

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.