The Model’s Story

by C. L. E.

London Society, vol. 6, issue 37 (1864)

Pages 533-540

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: Published in London Society, a popular British periodical, “The Model’s Story” is a short story that provides entertainment to its middle-class readers. This piece of Victorian fiction dives into the era’s themes of art and love, as well as London Society’s focus on light entertainment. In “The Model’s Story,” a young man pursues his passion by becoming an artist. While working in this profession, the artist paints portraits of unique individuals who tell their venturesome life stories. Throughout this tale, individuals are left to reflect on the stirring adventures of life, as well as the excitement of a thrilling tale.

I don’t know what it was that first induced me to become a painter. Everyone was against it.1For “Everyone” the original text reads “Every one.” My father thought it was madness. My mother said she was dreadfully disappointed at my foolish choice. My sisters wondered that I did not prefer the army, the bar, a public office, anything, rather than such a profession. As for Dr. Dactyl (then head-master of Muzzington School, where I was pursuing my curriculum), he privately informed me in his library that any young man who would wilfully abandon the study of the classic authors at my age, and thus forgo the inestimable advantages of a university career, must be in a bad way.

The truth is, the doctor and I had not been on the best of terms. Long before I began to draw in an orthodox way from the ‘antique,’ at Mr Mastic’s in Berners Street, I had had an idle knack of scribbling; and, in my school hours, this youthful taste frequently developed itself in the form of caricature. I believe I might have filled a portfolio with sketches of my schoolfellows. Podgkins, the stout boy, in his short trousers; Dullaway the tall dunce in the fourth form, who was always blubbering over his syntax; Mother Branbury, who came to us regularly on Wednesdays and Saturdays with a tremendous basket of pastry, and with whom we used to run up a monthly ‘tick,’– all these characters, I recollect, were depicted with great fidelity on the fly-leaves of my Gradus and Lexicon. Nor did the doctor himself escape. His portly form, clothed in the picturesque costume of trencher-cap and flowing robe, was too magnificent a subject to forego; and many were the sheets of theme-paper which I devoted to this purpose. One unlucky cartoon which I had imprudently left about somewhere, found its way into the doctor’s awful desk, where it was recognized weeks afterwards by Simpkins, a third form boy, who had been sent to fetch the birch from that awful repository; and whose information to me fully explained how it came to pass that I had lost at one and the same time my favourite sketch and the doctor’s affections.

I need scarcely say that I made no endeavour to reclaim this lost property when I took my final congé.2Congé: dismissal. The doctor gave me a cold and flabby hand–remarked, with a peculiar emphasis, that if I persisted in my wish to become an artist, he only hoped I should devote my energies in the right direction, and not degrade my pencil by—. I guessed pretty well what he was going to say; but as we saw the Muzzington coach draw up at the moment outside his study window, he was obliged to stop short in his lecture. I had just time to get my traps together, to give the doctor’s niece, Mary Wyllford (a dear little soul of fourteen, who had brought me a paper of sandwiches), a parting salute behind the dining-room door, shake hands with my schoolfellows all round, jump on the ‘Tantivy’ coach beside the driver, and roll out of the town.

Of all the various fingerposts which Time sets up along the road of life, there are a few, I think, which remember better than that one we leave behind us on the last day of school. The long anticipated emancipation from a discipline which in our youthful dreams we think can never be surpassed for strictness afterwards–that rose-coloured delusion which leads us to look forward to the rest of life as one great holiday; are not these associated forever with the final ‘breaking up?’3For “forever” the original text reads “for ever.” What student of the Latin grammar ever drew a moral from his lessons?

‘O fortunatos nimium sua si boni nôrint.’4This is a misquotation of the Latin phrase, ‘O fortunatos nimium, sua si bona norint, agricolas’ from Virgil’s Georgics, meaning ‘Oh how very happy farmers would be, if only they could see how lucky they are.’

There is the text staring him in the face, and yet he refuses to listen to it. The golden age, in his opinion, has begun, instead of ended. All care, he thinks, is thrown aside with that old volume of Euripides. At last he is to join a world in which the paradigms of Greek verbs are not important; where no one will question him about the nature of Agrarian laws. Ah, gaudeamus igitur!5Latin for “therefore let us rejoice.” Have we not all experienced this pleasure?

I had purchased some cigars at Mr. Blowring’s, in the High Street (his best medium flavoured, at five-pence apiece), with the audacious notion of lighting one up at the school door; but when the time arrived, I confess my courage failed me. I waited until we were clear of the town to produce my cigar-case, and presently had the mortification of turning very pale before the coachman.

A month or so after that eventful day, I was established as an art student in Berners Street, London. I had a hundred a year, which, my father assured me, was an ample allowance, to live upon, and the entrée to Mr. Mastic’s academy, hard by. The expenses of my tuition at that establishment were defrayed out of the parental purse; and when I state that fifteen shillings a month was the sum charged for admission, it will be observed that the outset of my career was not attended by much investment of capital. Mr. Mastic had formed a fine collection of casts from the antique, which were ranged around his gallery for the benefit of his pupils. There was the Fighting Gladiator stretching his brawny limbs half across the room; and the Discobolus, with something like the end of an oyster-barrel balanced in one hand; and the Apollo, a very elegant young man in a cloak, who was supposed just to have shot at someone with an invisible bow and arrow, and seemed very much surprised at the result; and the Medici Venus, whom one of our fellows always would call the medical Venus, on account of its frequent appearance on a small scale in the chemists’ shops, bedecked with galvanic chains and elastic bandages for feeble joints and varicose veins.6For “someone” the original text reads “some one.” And there was the Venus of Milo, whose clothes seemed falling off for want of arms to hold them up; and chaste Diana striding along by the side of her fawn; and Eve, contemplating herself in an imaginary fountain, or examining the apple in a graceful attitude. With all these ladies and gentlemen in due time I made acquaintance, learned to admire their exquisite proportions, and derive from them and the study of Mr. Mastic’s diagrams that knowledge of artistic anatomy which I have since found so eminently useful to me in my professional career.

Rumour asserts that Mastic had himself dissected for years at Guy’s Hospital, and had thus acquired great proficiency in this branch of his art; which, indeed, he seemed to value beyond all others. He knew the names of all the muscles by heart, their attachments, origin, insertion–what not? Frequently I have known the honest fellow remove his cravat to show us the action of the sterno-cleido-mastoid; and he was never so happy as when he was demonstrating, as he called it, in some fashion, the wondrous beauties of the human form. Mastic never exhibited his pictures. The rejection of some of his early works by the Royal Academy had inflicted a deep wound upon the painter’s sensibilities, which time could never heal. He talked with bitter scorn of the establishment in Trafalgar Square; hung the walls of his atélier with acres of canvas, and was often heard to remark that if the public wanted to see what he could do, they might come there and judge of his merits. I regret to add that few availed themselves of this golden opportunity. It might be that his art was of too lofty a character to suit the age; or, perhaps–as neglected genius is wont to do–he slightly overrated his own abilities. Certain it is, that as year after year he devoted his talents to the illustration of history, or the realization of the poet’s dreams, these efforts of his brush, whether in the field of fact or fiction, remained unheeded in his studio, lost to all eyes except our own; and even we, his faithful pupils, did not perhaps appreciate them to the extent which they deserved. As we profited by his experience, we improved our judgement, and by-and-by began to find faults where we had once seen nothing but perfection. I became a student of the Royal Academy, was admitted to paint in the ‘Life School,’ and soon grew ambitious enough to treat subjects of my own. The Preraphaelite school had just arisen. Men were beginning to feel that modern art had too long been looked upon as an end rather than a means, and preferred returning to an earlier and less sophisticated style of painting. They said, let us have truth first, and beauty after-wards if we can get it, but truth at any rate. And the young disciples in this new doctrine of æsthetics suffered endless ignominy and bitter sneers from old professors and fellow-students; but they did not care. They went on in the road they had chosen–painting life as they saw it. They represented humanity in the forms of men and women, and did not attempt to idealize it into a bad imitation of the Greek notion of gods and goddesses. When they sat down before a landscape, their first object was to copy nature honestly, without remodelling her form and colour to suit a ‘composition.’ And, as time went on, they had their reward. Yes; magna est veritas et praevalebit.7Latin for: “truth is mighty and will prevail.” At last their labours were appreciated; and I am proud to think that my first efforts were stimulated by the example of such men as Millais and Holman Hunt.

My father’s allowance to me was, as I have said, only a hundred a year; and I soon began to feel the necessity of earning money. To a young artist without patronage that is perhaps an easier matter in these days than it was some forty or fifty years ago. Unless a man was ‘taken up,’ as the phrase went, by some wealthy patron–a Sir George Beaumont or a Duke of Devonshire–he could not then hope to make a living by his profession at its outset. But in these days of cheap illustrated literature, fair average ability may often find a field for work in drawing on the wood. I was lucky enough to become connected with a popular periodical, and managed to eke out my income by using my pencil in its service.

There is something very delightful in handling the first money that one has earned. To know that you are under no obligation for it, that it is yours by the strictest law of justice, that you have actually turned your brains or fingers to some account at last; that your service in the world is acknowledged substantially in those few glittering coins or that crisp, pleasant-looking slip of paper; there is a charm, I say, about the first fee of honorarium which we never experience again. Hundreds may be paid into our bankers when we are famous. Our great-aunts may shuffle off this mortal coil, and leave us untold treasures in the Three per Cents; but we shall never look upon a guinea or a five-pound note with the same degree of interest which we felt in pocketing the price of our earliest labour.

I took care not to let this employment interfere with my ordinary studies. My object was to be a painter, not a draughtsman; and it was perhaps fortunate that I did not get more magazine work than sufficed to keep me out of want, just then, or I might have neglected my palette altogether.

One of the earliest commissions which I obtained was through the influence of a little lady whose name I have already mentioned–Mary Wyllford. Within two years after I had left the doctor’s establishment he had received a colonial appointment; and when he left his native country, deeply beloved and regretted by his old pupils (whose pious tribute to his worth finally took the form of a silver inkstand), Mary came up to town to live with her mother, a young and still handsome widow of eight-and-thirty, who had just returned from the Continent. I had often felt some surprise that Mrs. Wyllford should have voluntarily separated herself for so long a time from her child; but Mary now made no secret of the fact that her mother had been in very poor circumstances, and that, as her uncle the doctor had kindly offered to take charge of her, Mrs. Wyllford, unwilling to become a further burden on her brother-in-law, had accepted the situation of companion to a lady who was travelling abroad. The unexpected death, however, of a distant relative, had not only placed them henceforth beyond the reach of want, but actually would insure for Miss Mary a very pretty little fortune by the time she came of age.

The first thing the good little girl did after they had settled in their new house, was to persuade her mother, whom I found to be a very agreeable and accomplished woman, to let me paint her portrait. I have studied many heads since Mrs. Wyllford sat to me, but never remember one with which I was more impressed at first sight. Hers was a beauty of which it might truly be said that it improved with age. Just as the first autumnal tints only enhance the charms of what was last month’s summer landscape, so some faces, I think, become more interesting in middle life than in the fullest bloom of youth. There was sometimes a sweet sad smile on Mrs. Wyllford’s features, which told of patient suffering an unwearying love through many a year of trial. I did not know her history then, but had heard that she had married as a schoolgirl, and that the union had been an unhappy one. Mary never mentioned her father’s name to me, and I took care to avoid a subject which I knew would be painful to her. She had now grown up a fine, fair-haired, rosy-cheeked girl of seventeen, and, after the renewal of our acquaintance, I confess that the boyish affection which I felt for her at school soon ripened into a stronger passion. In short, I fell in love with her, and, in the language of diffident suitors of the last century, had reason to hope that I was not altogether despised. But how could I, a young tyro, just entering my profession, without prospect of an inheritance for years to come, how could I venture to make known my case without the possibility of offering her a home? As the little pinafored dependent on the doctor’s bounty, she was an object of compassion; but as the heiress of 500l a year, she might marry a man in some position–nay, would probably now have many such lovers at her feet. I was determined, at all events, to defer saying a word to her on the subject until there was some prospect of my professional success. I was engaged on a picture which it was my wish to send to the ensuing Royal Academy Exhibition. If it were accepted, I thought I might venture to look for further commissions; and the bright hope of Mary’s love stimulated me to increase industry.

The subject I had chosen for illustration was the statue scene in the ‘Winter’s Tale,’ at the moment when Leontes stands transfixed before Hermione, hardly daring to recognize her as his living wife.8A reference to William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. I had had great difficulty in procuring a model for Leontes; but at last succeeded in engaging on through the assistance of a brother-artist, who sent him to me one morning with a letter of recommendation. He was a tall, well-made man, whose age perhaps was under forty–rather too young, in fact, for the character he was to personate, if his hair, which was turning prematurely grey, had not supplied the deficiency.9Original text reads: “well-made made man.” I gathered from my friend’s letter that he had seen better days–and, indeed, the moment he entered my studio I was struck by his appearance. His features bore all the evidence of gentle birth; and yet there were marks of want and care upon them which seemed incompatible with their refinement. His manner was particularly quiet and subdued, and, unlike most models whom I had engaged, he seldom spoke, even during the short interval in which he was allowed to rest from what is technically called the ‘pose.’

After a few sittings he seemed to gain confidence, and, finding I was interested in him, gave me, one dark November morning, while a dense black fog obscured the light and rendered painting impossible, the following account of his life.

‘You are right, sir,’ said he, ‘in supposing that I was born in a better station of life than this. I’ve been too proud–perhaps too foolishly proud–to own it to those who have employed me in this way before; but there is something about you which leads me to trust you with my secret–or, at least, that part of it which I dare to speak of.’

I assured him that I would not betray his confidence, and he went on, his voice trembling as he spoke:

‘I was the only son of an officer in the Indian army, who had married late in life, and at the time of my birth was living on half-pay in the west of England. My mother died when I was ten years old; and my father, who indulged me in every way as a child, dreading what he conceived to be the bad influence of a public school, determined to educate me himself at home. The motives which induced him to make this resolution were, no doubt, very good; but experience has since taught me that, in doing so, he made a grievous mistake. A private education may, indeed, answer very well in exceptional cases; but as a rule, and particularly when boys are waywardly inclined, it is the worst of all systems. When I went to College, at the age of nineteen, I had seen nothing of the world. I found myself suddenly emancipated from parental control, in the midst of dangerous pleasures which had all the charm of novelty, and associating with companions whose example no experience had taught me to avoid. Naturally impulsive in my temperament, I was soon led away, step by step, into follies and vices which I had never learnt to see in their proper light. I soon became deeply involved in debt, and, much to my father’s disappointment, left Oxford without taking a degree.

‘He received me with coldness, and even severity, and told me that if I ever hoped to re-establish myself in his favour, I must speedily reform my habits, and enter at once on the study of the profession which he had chosen for me. It was his wish that I should qualify myself for the bar; and with this end in view, I was placed in a solicitor’s office at H—.

‘I can conscientiously say that at this period of my life my habits were steady, and that I looked forward with earnestness to taking that position in the world which my birth and education ought to have given me. I had, moreover, an additional incentive to industry. I became attached to the daughter of a gentleman who had been one of my father’s oldest friends. She had been left an orphan, and in charge of the lawyer’s family with whom I had become professionally connected. As we were both extremely young, her guardian, although he knew that my affections were returned, would not hear of any formal engagement until I had shown, by an altered course of life, that I deserved her. In due time I came up to London to read law; and had scarcely been called to the bar when my father died. Deeply as I then felt his loss, it is some satisfaction at least for me to think that I was with him in his last moments; that he freely forgave me the pain I had caused him; and–grieved as I am to say it–that he did not survive to see the subsequent misery of which I still seemed doomed to be the author.

‘Finding that I was now in the possession of a small inheritance, I determined not to leave H—- until I could assure myself of the prospect of a speedy union with her for whose sake I had laboured long and steadily, and without whose gentle influence I felt I might soon relapse into former habits. I had kept my promise. I had relinquished all thoughts of pleasure until I had attained a qualified position; and now I came to claim my reward. Her guardian admitted the justice of my plea; the dear girl herself blushing avowed her affection, and within twelve months after my father’s death we were married.

‘I found my wife everything that I had pictured her. Kind and gentle as she was lovely, she had ever a sympathizing word for me in trouble or anxiety; and though her husband was always her first consideration, she gained the admiration of all our friends by her sweet and winning manner. I look back upon the first few years of our marriage as the happiest in my life. I had already begun to practise at the bar with some prospect of success, when an unforeseen calamity occurred, which combined with my own selfish conduct, completely turned the tide of our good fortune.

‘It was soon after the birth of our first–our only–child, that my poor wife was seized with a dangerous illness, on recovering from which she was ordered change of air. The waters of a celebrated German spa were mentioned as likely to suit her case; and hoping to compensate by economy for what I might lose in professional practice, I determined to accompany her on the Continent.

‘The little watering place to which we had been recommended was by no means expensive. We hired furnished lodgings in a good situation; my wife soon found the benefit of the air, and was on a fair road to recovery, when our baby was also taken ill. To a man who, like myself, had never been accustomed to the society of children, the weary noise and constant crying of infants are extremely irritating, and, having brought an excellent English nurse with us, I soon became glad to escape from a source of annoyance which I could not remove, and which would soon have tried a less nervous man than I then was. Unfortunately the adjoining town–like most German spas–had its kursaal, and its gaming-table.10Kursaal: a public room at a health resort. At first the beauty of the gardens there, which were laid out with great taste, attracted me. An excellent band played on the grounds; and when my wife was prevented by her domestic duties from accompanying me, I frequently walked there alone, wondering that so many people could bear to throng those close and crowded rooms, when there was so much that was attractive outside.

‘One unlucky morning a heavy shower of rain compelled me to take shelter within the building. I walked about from room to room to wile away the time, and at last found myself by the rouge-et-noir table. At first I looked on out of curiosity; and was surprised to find, after all I had heard of the horrors of gambling, that here it was conducted in so quiet and orderly a manner. I watched the croupiers, now raking in, now doling out the glittering coin. I watched the players, men, women, even children, throwing down their florins with apparently a listless air. I little thought beneath that assumed indifference what aching brows and anxious hearts were there. A little girl of ten had just won a large heap of gold, and ran away with it to her mother, who was knitting on a bench outside. How well I remember her smiling happy face as she poured the money into the woman’s lap…(Good God! what may that mother have since had to answer for?)…I could resist no longer. I flung down a napoleon, and presently doubled my stakes–another, and won again. I left the table richer by some pounds than when I went to it. Would that I had lost every sou in my pocket! I might then have left the rooms forever. As it was, encouraged by success, I went the next day, and the next–sometimes losing, sometimes winning. At last, I grew bolder, and played for higher stakes, and then…why should I linger over the details of this mystery? It is an old story. I went on and on, incurring fearful losses–still hoping to retrench–and rose at length from that accursed board–a beggar.

‘If even then I had had the courage to tell my wife everything, to implore her forgiveness, it might not have been too late to retrieve my fortune, or at least have gained our bread in some humble, but honest employment. But I dared not. I have braved since many a danger by sea and land, and faced what seemed to be inevitable death in many shapes, but I could not then endure to meet her calm sweet face–to take our child upon my knee again, and bear the agony that must ensue from such confession. I knew that my wife expected her old guardian and his family to join us the day after my ruin was completed. I knew that at least the little property she would inherit on coming of age would be hers. Little as it was, it might keep them from starvation. Why should I return to a home which I had blighted and drag those innocents down into the slough of misery which my own folly had created? I was still young, strong, and healthy, and I determined to seek my fortune alone–to earn subsistence by the sweat of labour. My mind was made up. I wrote a few hurried lines to my wife, and then tore myself away–from her–from my little one, forever.11For “forever” the original text reads “for ever.”

* * * *

‘My life since that never-to-be-forgotten day has been one of extraordinary vicissitude; my means sometimes rising to the level of a competence, sometimes reducing me to the verge of mendicancy. For years past I have sought my living in different countries, and in various ways, and had nearly realized a little fortune in California, as a gold-digger, when I lost everything on the voyage home by shipwreck. I worked the rest of my passage to England before the mast, and an artist who was on board, knowing my straitened circumstances, gave me his address in London, and has since employed me as a model. This led to other introductions, and among others to yourself, sir. You were good enough to express an interest in me, and I have told you my story; but I beseech you, spare me the sad humiliation which a knowledge of my previous life would surely bring me in the eyes of those from whom at present I must earn my living. I have suffered long and bitterly for the past, though, God knows, not more than I deserve. But I still retain pride enough to beg that you will not inquire my name. Let me be known to you and to your friends as “George,” the artist’s model.12For “and” the original text reads “aud.”

The fog had cleared away at the conclusion of this strange recital, but I had no heart to paint that day. I was almost sorry I had heard poor ‘George’s’ story. I was in no position to help him, and the aspect of his bronzed and weatherbeaten face, now rather excited my sympathy as a man than raised my admiration as an artist. It is lucky, thought I, that the head of Leontes is nearly finished; this story would have altered its character considerably on my canvas. The man was fit for better things than this–yet how could I help him? I was only just beginning to support myself–and moreover, if I had had the means, I felt sure he would have accepted nothing in the form of charity. Warmly expressing my sympathy, and assuring him that he had not misplaced his confidence, I excused myself from further work that afternoon, determining, in the meantime to reflect on the best means to adopt for his assistance.13For “meantime” the original text reads “mean time.” He thanked me for what I had said, promised to return on the following day, and went off to fulfil another engagement.

It was only when he had gone that I remembered many questions which I should have liked to ask him respecting the fate of those whom he had so cruelly deserted. And yet if they had been alive–if he had tried, or wished to find them out again–would he not have told me? At one moment I felt ashamed for commiserating a man who had thus selfishly abandoned those who should have been dearest to him (even under the circumstance which he had detailed); at another I realized the bitter trials he had undergone;–thought of the anguish he must have endured, before he could make up his mind to take that fatal step, and felt how heavy had been his punishment.

I determined to consult my good benefactress, Mrs. Wyllford, on the subject. She was coming the next morning with her daughter, to look at my picture. I confess that the prospect of seeing Mary generally put everything else out of my head; but on this occasion I was not sorry, when the time arrived, to find that her mother entered my studio alone. The ‘little housekeeper,’ as she used playfully to call her daughter, had been detained by some domestic matters, and would follow her presently.

I thought I would first show Mrs. Wyllford my picture, and then, while his portrait was before her, detail the outline of poor ‘George’s’ story, and endeavour to enlist her sympathies in his behalf. She sat before the easel, looking, as I thought, younger and prettier than she had ever seemed before. The subject I had chosen was familiar to her–indeed she had herself suggested it. Camillo was supposed to be addressing Leontes in the lines–

‘My lord, your sorrow was too sore laid on:

Which sixteen winters cannot blow away,

So many summers dry: scarce any joy

Did ever so long live; no sorrow,

But killed itself much sooner.’14From William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale Act V, Scene 3.

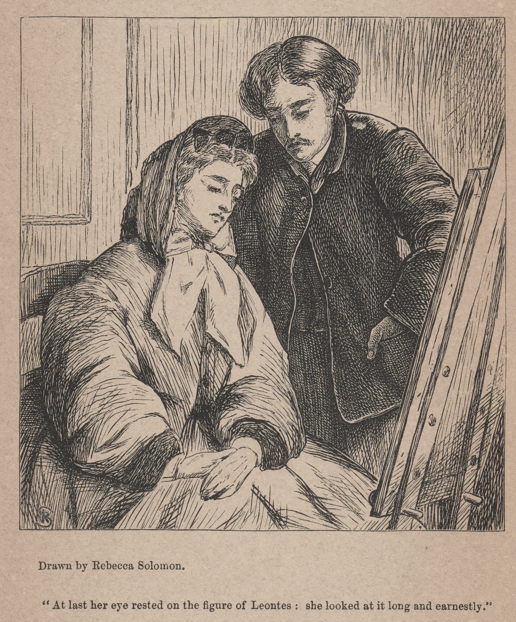

She kindly praised the attitude of Hermione, the dresses and accessories of the picture, which I had studied with some care. At last her eye rested on the figure of Leontes. She looked at it long and earnestly,

‘I want you to be interested in that head,’ I said at length, in joke.

‘Why?’ said she quickly, and growing, as I thought, rather pale as she spoke. ‘Was it studied from nature? I see you have only just finished it: the–the paint is hardly dry, and–would you mind opening the window?–the smell of the oil is a little too strong for me.’

My studio window was one of those old-fashioned lumbering contrivances which swing on a pivot. I went behind the chair to comply with her request, and while engaged in arranging a prop to keep the sash-frame in its place, I began to tell her briefly the story of my model’s life. I was interrupted by a loud cry of pain, and turned round to find Mrs. Wyllford falling from her chair. I rushed to her assistance, and found that she had already fainted. There was water in the adjoining room, and I hastened to fetch it. As I hurried back I was met by George, who had just come to keep his appointment, and to whom I hastily explained what had happened. Between us we lifted the poor lady up, and laid her on the sofa. In doing this, her head had fallen on my arm, and it was not until I raised it, that we saw how deadly pale she was. I poured some water between her lips and begged George to get some doctor’s help without delay. But he stood like one transfixed, muttering incoherently.

‘For goodness’ sake,’ I said, ‘make haste–no time is to be lost! What is the matter?

‘I think I am going mad,’ said he as he fell upon his knees beside the couch. ‘Raise her head a little more-this way, boy, this way,’ he shrieked, in pitiable accents. ‘Heavens! how like she is to–Mary–Mary.–O God! it is my wife herself!’

* * * *

It was indeed the wife that he had left ten years ago–who had survived his cruel desertion–struggled with poverty and many trials–maintained herself heroically by her own exertions, and was now, thank God! in a position to save him from the misery which his folly and selfishness had occasioned. She had recognised his portrait while I was telling her George Wyllford’s story, little thinking how closely it was interwoven with her own; and it was the sudden shock which occasioned her swoon. I have little more to add in explanation. Within twelve months from the date of this event, I married Mary Wyllford. Her father is an altered man. His wife’s fortune was an ample one, but he never spent a penny of it without her consent. My picture was accepted at the Royal Academy Exhibition, and, wonderful to relate, was well hung. Since then I have painted from hundreds of men, women, and children; but I can safely say that I never heard from any of my sitters, any narrative which has interested me so much as the Model’s Story.

C.L.E.

Word Count: 6234

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Eloise Johnson

Kelsi Gillies

Taylor Etherington

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

10 March 2025

Last modified

3 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | For “Everyone” the original text reads “Every one.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Congé: dismissal. |

| ↑3, ↑11 | For “forever” the original text reads “for ever.” |

| ↑4 | This is a misquotation of the Latin phrase, ‘O fortunatos nimium, sua si bona norint, agricolas’ from Virgil’s Georgics, meaning ‘Oh how very happy farmers would be, if only they could see how lucky they are.’ |

| ↑5 | Latin for “therefore let us rejoice.” |

| ↑6 | For “someone” the original text reads “some one.” |

| ↑7 | Latin for: “truth is mighty and will prevail.” |

| ↑8 | A reference to William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. |

| ↑9 | Original text reads: “well-made made man.” |

| ↑10 | Kursaal: a public room at a health resort. |

| ↑12 | For “and” the original text reads “aud.” |

| ↑13 | For “meantime” the original text reads “mean time.” |

| ↑14 | From William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale Act V, Scene 3. |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.