My Blind Sister

by Harriet Parr

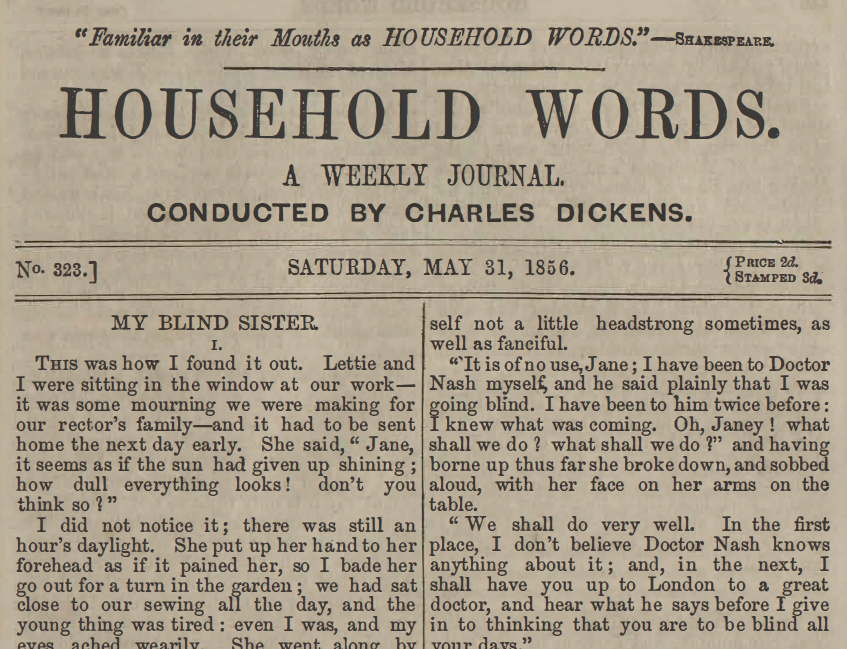

Household Words: A Weekly Journal, vol. 13 (1856)

Pages 323-461

Introductory Note: “My Blind Sister” is a charming, domestic story of two sisters and how they deal with the developing blindness of the youngest sister. This story also includes a marriage plot and touches on the rapidly developing field of medicine as the sisters search for a cure for blindness. “My Blind Sister” features a first person, female narrator and a style of fiction that closely imitates a nonfiction, personal essay.

I.

This was how I found it out. Lettie and I were sitting in the window at our work—it was some mourning we were making for our rector’s family—and it had to be sent home the next day early. She said, “Jane, it seems as if the sun had given up shining; how dull everything looks! don’t you think so?”

I did not notice it; there was still an hour’s daylight. She put up her hand to her forehead as if it pained her, so I bade her go out for a turn in the garden; we had sat close to our sewing all the day, and the young thing was tired; even I was, and my eyes ached wearily. She went along by the flower-bed, and gathered a few roses—we were in the middle of July then—and gave them to me through the window, saying that she would go down into the town for some trimmings we wanted to finish the dresses. I would rather she had stayed at home, and replied that the shops would be shut; but she was not listening, and went away down the path as I spoke. It was dusk when she came back; I had just shut the window, and was lighting my candle; she said, “I could not get the fringe, Jane,” and then laying her bonnet on the dresser, took up her work. After she had sewed perhaps five minutes she dropped her hands on her knees, and such a strange, hopeless expression came into her face, that I was quite shocked and frightened.

“What ails you, Lettie? what can have happened ?” I asked, suspecting I scarcely knew what.

She looked at me drearily in silence for some moments, and then said hastily, “I might as well tell you at once, Jane,— I’m going blind.”

My work fell to the ground, and I uttered a startled cry.

“Don’t take on about it, Jane; it can’t be helped,” she added.

“It is only a fancy of yours, Lettie; I shall have you to Doctor Nash in the morning. What has made you take such a notion into your head all at once,” said I, for I thought this was another nervous whim. Lettie had been a good deal indulged by our mother before she died, and had shown herself not a little headstrong sometimes, as well as fanciful.

“It is of no use, Jane; I have been to Doctor Nash myself, and he said plainly that I was going blind. I have been to him twice before: I knew what was coming. Oh, Janey! what shall we do? what shall we do?” and having borne up thus far she broke down, and sobbed aloud, with her face on her arms on the table.

“We shall do very well. In the first place, I don’t believe Doctor Nash knows anything about it; and, in the next, I shall have you up to London to a great doctor, and hear what he says before I give in to thinking that you are to be blind all your days.”

She was a little cheered by this.

“To London, Janey! but where is the money to come from?” she asked.

“Leave that to me. I’ll arrange somehow.” It was very puzzling to me to settle how just then, but I have a firm conviction that where there is a will to do anything, a way may generally be found, and I meant to find it.

She took up her work, but I bade her leave it. “You will not set another stitch, Lettie,” I said; “you may just play on the old piano and sing your bits of songs, and get out into the fresh air—you have been kept too close, and are pale to what you were. Go to bed now like a good little lassie; I’ll do by myself.”

“But there is so much to finish, Janey.”

“Not a stitch that you’ll touch, Lettie: so kiss me good-night, and get away.”

“And you don’t think much of what Doctor Nash said?” she asked very wistfully.

“No! I’ve no opinion of him at all.” And hearing me speak up in my natural way (though my heart was doubting all the time), she went away comforted, and in better hope. I had put it off before her, because she would have given way to fretting, if I had seemed to believe what the doctor said; but, as I drew my needle through and through my work till three hours past midnight, I had often to stop to wipe the tears from my eyes.

There were only two of us— Lettie and myself— and we had neither father nor mother, nor indeed any relatives whom we knew. Lettie was seventeen, and I was four years older. We were both dressmakers, and either worked at home or went out by the day. We lived in a small, thatched, three-roomed cottage outside the town, which had a nice garden in front. Some people had told us that if we moved into the town we should get better employ; but both Lettie and I liked the place where we had been born so much better than the closed-in streets, that we had never got changed, and were not wishful to. Our rent was not much, but we were rather put to it sometimes to get it made up by the day, for our landlady was very sharp upon her tenants, and if they were ever so little behindhand, she gave them notice directly.

I set my wits to work how to get the money to take Lettie to London; but all that night no idea came to me, and the next day it was the same. With two pair of hands we had maintained ourselves decently; but how was it going to be now that there was only one! Rich folks little think how hard it is for many of us poor day-workers to live on our little earnings, much more to spare for an evil day.

II.

Sunday found me still undecided, but that was our holiday, and I meant to see Doctor Nash myself while Lettie was gone to chapel. She made herself very nice, for she had a modest pride in her looks which becomes a girl. I thought her very pretty myself, and so did the neighbours; she had clear, small features, and a pale colour in her cheeks, soft brown hair, and hazel eyes. It was not easy to see that anything ailed them, unless you looked into them very closely, and then there was a dimness to be seen about them, which might be disease. She had put off thinking about herself, and was as merry as a cricket when she went down the lane in her white bonnet and clean muslin gown. She nodded to me (I was watching her from the doorway), and smiled quite happily. I was as proud of Lettie as ever my mother had been. She was always such a clever, warm-hearted little thing; for all her high temper.

When she was fairly gone, and the church bells ceased, I dressed myself in haste, and set off into the town to see Doctor Nash. He was at home, and his man showed me into the surgery, where I had to wait may-be an hour. When the doctor came in, he asked sharply why I could not have put off my visit till Monday; was my business so pressing? He did not consider how precious were the work-days to us, or may-be he would not have spoken so—for he was a benevolent man, as we had every reason to know; he having attended our mother through her last illness as carefully as if she had been a rich lady, though we could never hope to pay him. I explained what I had come about, and he softened then, but would not alter what he had told Lettie himself.

“She has been with me three or four times,” he said. “She is an interesting little girl; it is a great pity, but I do not think her sight can be saved—I don’t indeed, Jane.”

He explained to me why he was of this opinion, and how the disease would advance, more lengthily than needs to be set down here. Then he said he could get her admitted into the Blind Institution if we liked; and that I must keep her well, and send her out of doors constantly. And so I went home again, with very little hope left, as you may well think, after what I had heard.

I did not tell Lettie where I had been, and she never suspected. There was no chapel that afternoon, and we were getting ready to take a walk along the river bank, as we generally did on fine Sundays (for all the town went there, and it freshened us up to see the holiday people far more than if we had stopped at home reading our books, as many say it is only right to do), when one of our neighbours came in with her son. Mrs. Crofts was a widow, and Harry was studying medicine with Doctor Nash. They were both kind friends of ours; and, between Lettie and the young man, there had been for ever so long a sort of boy and girl liking; but I do not think they had spoken to each other yet. Lettie coloured up when Harry appeared, and went into the garden to show him, she said, the white moss-rose that was full of bloom by the kitchen window; but they stayed whispering over it so long, that I did not think it was only that they were talking about. Then Harry went out at the gate looking downcast and vexed, and Lettie came back into the house with a queer wild look in her face that I did not like. Mrs. Crofts said, “Is Harry gone?” and my sister made her a short answer, and went into the bed-room.

“Harry is going up to London very soon; I shall be glad to have the examinations over and him settled. Doctor Nash thinks very well of him; he is a good young fellow, Jane.” I replied that he had always been a favourite of mine, and I hoped he would do well; but, listening for Lettie’s coming to us, perhaps I seemed rather cold and stiff; for Mrs. Crofts asked if I was not well, or if there was anything on my mind; so I told her about poor Lettie’s sight.

“I’ve seen no appearance of blindness; Harry never said a word. You don’t think it can be true?” she asked. I did not know what to think. I was sure that, in that whispering over the rose-tree, my sister had told young Mr. Crofts; and I wished his mother would go away, that I might comfort her. At last she went. Then I called to Lettie, who came at once. She had been fretting; but, as she tried to hide it, I made no remark, and we went down the lane to the river meadows in silence. The first person we met was Harry Crofts. Lettie seemed put out when he joined us, and turned back. She stayed behind, and was presently in company with our landlady, Mrs. Davis, who was taking the air in a little wheeled chair drawn by a footman. Mrs. Davis had always noticed Lettie. Harry Crofts looked back once or twice to see if she was following; but, when he found she was not, he proposed to wait for her, and we sat down by the water on a tree trunk which lay there.

“This is a sad thing about Lettie’s eyes, Jane,” he said suddenly.

“Yes, it is. What do you think about them? Is there any chance for her?”

“Doctor Nash says not; but, Jane, next week Philipson, the best oculist in England, is coming to stay a couple of days with Nash. Let him see her.”

“I meant to try to get her to London for advice.”

“There is nobody so clever as Philipson. Oh! Jane, I wish I had passed—”

“Do you fancy you know what would cure her?”

“I’d try. You know, Jane, I love Lettie. I meant to ask her to be my wife. I did ask her this afternoon, and she said, No; and then told me about her sight—it is only that. I know she likes me: indeed, she did not try to deny it.”

“Yes, Harry, you have been so much together; but there must be no talk of marrying.”

“That is what she says.”

“She is right—she must just stay with me. You could not do with a blind wife, Harry: you, a young man, with your way to make in the world.”

He tore up a handful of grass, and flung it upon the river, saying passionately, “Why, of all the girls in Dalston must this affliction fall on poor Lettie?” and then he got up and walked away to meet her coming along the bank. They had a good deal of talk together, which I did not listen to; for their young hearts were speaking to each other—telling their secrets. Lettie loved him: yes, certainly she loved him.

III.

Doctor Philipson’s opinion was the same as that of Doctor Nash. Lettie was not so down-stricken as I had dreaded she would be, and she bade good-bye to Harry Crofts almost cheerfully when he went up to London.

“There, Jane, now I hope he’ll forget me,” she said to me; “I don’t like to see him so dull.”

That day Mrs. Davis sent her a ticket for a concert at the Blind Institution, and she went. When she came home to tea she told me that the girls and boys who sang looked quite happy and contented. “And why should I not be so too? what a number of beautiful sights I can remember which some of them never saw!” she added, with a sigh.

After this, imperceptibly, her sight went; until I noticed that, even in crossing the floor, she felt her way before her, with her hands out. Doctor Nash again offered to use his influence to get her admitted into the Institution, but she always pleaded “Let me stay with you, Janey!” and I had not the heart to refuse; though she would have had more advantages there, than I could afford her.

Not far from us there lived an old German clockmaker, who was besides musical, and acted as organist at the Roman Catholic Chapel in the town. We had known him all our lives. Lettie often carried him a posy from our garden, and his grandchildren came to me for patches to dress their dolls. Müller was a grim fantastic-looking figure, but he had a heart of pure gold. He was benevolent, simple, kindly; it was his talk that had reconciled Lettie, more than anything else to her condition. He was so poor, yet so satisfied; so afflicted, yet unrepining.

“Learn music — I will teach thee,” he said to my sister. So, sometimes in our little parlour, and sometimes in his, he gave her lessons in fine sacred pieces from Handel and Haydn, and taught her to sing as they sing in churches—which was grander than our simple Methodist hymns. It was a great delight to listen to her. It seemed as if she felt everything deeper in her heart, and expressed it better than before: and it was all her consolation to draw the sweet sounds up out of that well of feeling which love had sounded. I know that, to remember how Harry loved her, gave a tenderness and patience to her suffering which it would else have lacked. She, who used to be so quick with her tongue, never gave anybody a sharp word now.

I do not say much about our being poor, though, of course, that could not but be; still we had friends who were kind to us: even Mrs. Davis softened, and mentioned to me, under seal of confidence, that, if I could not quite make up the rent, she would not press me; but I fortunately had not to claim her forbearance, or else I do fear she could not have borne to lose a sixpence; and when it had come to the point we should have had to go like others: she was so very fond of money, poor woman! Lettie used to go to the Institution sometimes, where she learnt to knit, and net, and weave basket-work. Our rector (a better man never lived, or a kinder to the poor) had her to net covers for his fruit-trees, fishing-nets, and other things; and to knit woollen socks for himself and his boys; so that altogether she contrived to make what almost kept her. Now that the calamity had really come, it was not half so dreadful as it had seemed a long way off. Lettie was mostly cheerful. I never heard her complain, but she used to say, often, that there was much to be thankful for with us. She had a quiet religious feeling, which kept her from melancholy; and, though I did not find it out until afterwards, a hope that perhaps her affliction might some day be removed. Harry had put that thought into her mind, and I do not think I am overstating the truth in saying that his honest, manly affection for her was the great motive to his working so hard at his profession, in which he has since become deservedly successful and famous.

We had six very quiet years. It seemed to me as if Lettie had always, from the first, gone softly groping her way, and I had always led her to chapel and back. Harry studied in London; then we heard of him in Edinburgh; and at last his mother said he had gone to Paris; and she was half afraid he would settle there and marry a papist wife. Lettie looked sorrowful and restless for a day or two after that, but presently recovered her cheerfulness. We had not much change or variety at home. There was I for ever at my work, and Lettie at her music. She had gained a great deal of skill now; and many a time have I seen a knot of people standing at the corner of our garden hedge to listen to her singing. I have heard several grand public performers since then; but never one who could touch my heart and bring the tears into my eyes as my poor blind sister did. On Sundays, at chapel, we could hear her voice, clear and sweet, above all the rest; and, though our tunes were wild and simple—sung by her, they were beautiful. Sometimes she would go to St. John’s church for the sake of the organ and the chaunting, but I did not feel it right to change: habit is strong in slow, untaught people; and it did not seem as if I had kept my Sabbath, unless I said my prayers in the homely little chapel to which our mother had led us by the hand when we were children. Lettie loved the grand church music, and who could wonder at it, poor lassie? Once or twice when she begged me to go with her, it had seemed to fill my heart to pain almost; so how much more must it have excited her who was all fire and enthusiasm! She said it made her feel happier and better, and more thankful to God. Perhaps in losing one sense, her enjoyment through the others grew more intense.

IV.

At the end of these six years Harry Crofts came home. He was often at our house, and we liked having him; but, though Lettie seemed happy enough, he was uneasy and discontented. I have seen him stand beside the piano, and never take his eyes off her by the half-hour together; but his face looked quite gloomy. At last he one day said to me, “Jane, are you timid—I do not think Lettie is? She seems strong and well.” I knew he meant more than a simple inquiry after our nerves, and I asked if he thought he had found out a cure for my sister. He turned quite red.

“Yes; I believe I have. I saw an operation performed in Paris on a girl’s eyes similarly affected. It was successful.”

I said not a word. The prospect seemed too good, too beautiful to be true! Just at this minute Lettie came in through the doorway; there was sunshine behind her, and she appeared to bring it into the parlour with her. “Are you here, Harry?” she immediately asked.

It was a strange thing, that, although she neither saw him nor heard him speak, she was at once aware of his presence. He got up and took her by the hand, and brought her to me. “Tell her, Jane, or shall I?” he whispered. I signed to him to speak himself, which he did without hesitation.

“Lettie, have you courage to undergo an operation on your eyes which may restore your sight?”

She clasped her hands, and such a beautiful colour came flushing up into her face—you would have said it was like an angel’s face, it changed so brightly.

“Oh, yes! anything, anything, Harry, only give me that hope!” said she, softly.

I looked at him questioningly to ask if he had not better warm her of possible disappointment, and he said at once:

“Lettie, I ought to tell you that this operation may fail, though I do not fear that it will. For my sake, Lettie,” he added, in an under-tone.

“Well, then, for your sake, Harry,” she replied, with a low sigh. “Even if it should not give me back my sight, I shall only be as I am now.”

They went out into the garden together; and, from the earnest, gentle way in which Harry talked to Lettie, I know that he was preparing her for what she had to undergo. She did not want for courage in any circumstances, and I did not look for her being weak now.

The operation was performed during the following week. Doctor Philipson and Doctor Nash were both present, but Harry Crofts himself did it. His nerve was wonderful. Lettie behaved admirably too; indeed, nobody was foolish but myself, and when it was over I fainted. It was entirely successful; my sister has her sight, now, as good as I have. For several weeks we kept her in a darkened room, but she was gradually permitted to face the light, and the joy of that time is more than words can describe.

Harry Crofts soon after claimed her as his wife; and really, to say the truth, nobody had a better right to her. The report of the singular cure he had made, lifted him at once into consideration; and, as he made diseases of the eye his particular study, he is now as celebrated an oculist as Doctor Philipson himself: many persons indeed give him the preference. The operation, then thought so much of, is now of frequent occurrence; Lettie’s kind of blindness being no longer looked on as irremediable.

And this is all I need tell about our history; it is not much, or very romantic, but I am often asked about it, so I have just set down the truth.

Word Count: 4086

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Harriet Parr. “My Blind Sister.” Household Words: A Weekly Journal, vol. 13, 1856, pp. 323-461. Edited by Maddie Lazaro. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 12 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/2555/.

Editors

Maddie Lazaro

Linde Fielding

Quinn Taylor

Cosenza Hendrickson

Posted

21 March 2020

Last modified

11 July 2025