The Shroud

The Butterfly, vol. 1 (1899)

Pages 203-214

Introductory Note: “The Shroud” by Kennett Burrow is the comically tragic tale of two women from a small village who have an uneasy and unexpected relationship to one another. The tale was submitted to the literary magazine The Butterfly, which was intended to be humorous and irreverent. Though the tone of the story doesn’t seem so humorous at first, like many stories in The Butterfly, Burrow does his best to shock and surprise his readers at the end.

The shop was absurdly small, so small that a single customer filled it; but as the customers seldom came, Miss Nulty was not perplexed by any schemes for enlargement. It was not that her neighbours did not support her as far as they could—they did their best, but there were so few of them that even the briskest commercial enterprise would have been wasted. The hamlet had been decaying for years, almost for generations; the young people had left it, the old remained because the outer world had no need of them. The place was old, mildewed, unnecessary; a prey to sea-mists and the insidious moisture of a low coast.

Miss Nulty sat in her shop for a certain number of hours every day, year in, year out, making various garments with a slowness that precluded all hope of profit. Most of this work she did for the vicarage, a very little for such of her neighbours as were too old to see. When she was not in the shop, she was upstairs. There was no back room; the staircase ran up from behind her chair, and was so narrow and dark that it gave the old lady’s nerves a good deal of trouble even after knowing it for thirty years.

In the window of the shop were a few things which rather indicated what she did not sell than what she did—a small collection of sweets in bottles, all stuck together and faded in colour, two or three tin whistles, a bowl of glass marbles, and half-a-dozen peg and whip tops. Nobody wanted these things, because there were no children left in the village; but once a week they were taken out, carefully dusted, and as carefully put back again. This process was known as “cleaning stock,” and occupied the greater part of every Monday morning.

One afternoon Miss Nulty sat in her shop, her old head bent low over her sewing, her old eyes wearied by working in a bad light. A less conscientious woman would have increased the size of her stitches; but Miss Nulty was an artist, and the greater the difficulty, the more persistently she toiled. She might have lit a lamp, but oil cost money; besides, she preferred twilight, it suited her mood, and made contrasts less sharp.

There was not a sound outside but the slow drip of moisture from the eaves of her cottage, the occasional melancholy crow of a damp, disheartened cock, and now and then a footstep that never came so far as Miss Nulty’s door. She was waiting for a footstep, and each time she raised her head, and listened eagerly. With each disappointment she bent over the sewing again, and sighed.

At last, however, half the remaining light was darkened by a figure that stood in the doorway. Miss Nulty dropped the work into her lap, and smoothed it with chilly, wrinkled fingers.

“Come in, Lisbeth,” she called, “come in and tell the news. Dear, how wet ’tis!”

Lisbeth entered, and sat down on an empty soap-box, which served for chair.

“Ay, you may say that, Mary. Wet it always was and always will be in this village. There! ’tis no use grumblin’.”

“No, I s’pose not.”

“I couldn’t get off before.”

“You must be main tired, Lisbeth.”

“I don’t grumble—not a word; but it’d a’most be a comfort if he were took.”

Miss Nulty’s hands closed tightly together.

“You shouldn’t say that, Lisbeth. He’s worked for you and now you’ve got the chance to do a bit for him. He’s been a good husband, and now he’s on his back—”

“There, how you talk! Anybody’d think I’d spoke against him!”

“I didn’t mean that. People take things different. I dare say ’tis tarr’ble wearin’, this watchin’ and nursin’.”

“Tarr’ble,” said Lisbeth; “and no good comes of it, nor can, so Doctor says.”

“How is he to-day?” Miss Nulty asked the question fearfully, and under her breath.

“Just the very same. He lays all day with his eyes open, a-starin’ at the ceilin’ as though it had pictures on it. He can’t move, poor soul, and when he do speak ’tis tarr’ble hard to catch it.”

“P’raps, as you say, Lisbeth,” said Miss Nulty softly, “he’d be better gone.”

“Doctor says he may go any minute.”

There was a long silence. The little shop seemed to grow together in the deepening dusk as though it shivered, the melancholy November wind soughed and whimpered without, and still the drip, drip continued like the ticking of a clock. Miss Nulty’s thoughts were far away from her surroundings; she was back in the time when she had been young and even pretty, and the blood danced.

“Why don’t you have a light, Mary?” Lisbeth asked.

“I like the dark best.”

“But you couldn’t see to serve a customer.”

“There won’t be another to-day.”

“Well, I s’pose you do know best.”

After another pause Miss Nulty asked:

“Might I see him, Lisbeth, just to let him know the village hasn’t forgot him?”

Lisbeth could not see the flush on the other’s usually bloodless cheeks, nor was she acute enough to catch the strained anxiety in the tone.

“To-morrow, p’raps, if you’d come ‘bout ten o’clock, when I’ve put him straight for the day.”

“Thank you, Lisbeth.”

“I’ll tell him you’re comin’—it might cheer him up like.”

“Do you think it will?”

“Ay; they’re main queer when they’re sick.”

“At ten o’clock, you say?”

“’Bout ten.”

“I’ll not forget.”

“I must be goin’ now.”

“Good-night, Lisbeth. If there’s any little thing he’d fancy, I could easy make it; I’ve more time than you.”

“He did speak once of toffy-apples.”

“I can make them fine.”

When Lisbeth had gone, Miss Nulty still sat in the dark shop, her work for once neglected, her mind sadly busy with the past.Toffy-apples! She had made him some long before he had ever met Lisbeth, and he remembered it! There was such poignant comfort in the thought, that she must needs weep a little, even though it was the worst thing in the world for weak and over-wearied eyes. How gladly she would have nursed him, looking for no reward beyond the mere fact that he still lived, however wrecked in mind and body. She had never complained, even when he had turned from her to Lisbeth; she had never tried to make mischief between them. Miss Nulty was a poor, weak little woman, to whom love was everything, so weak that she could not fight to keep it: when it was taken away, she lived on its memory, and put what heart remained in her into neat stitches and the conduct of her tiny shop. All her womanly instincts, which had budded with such fair promise, were turned aside to the dexterous manipulation of a needle and the custody of five pounds worth of stock.

At last she lit a lamp, and made herself a cup of tea, boiling the kettle over a little spirit stove. Fires were too expensive for one old lady, and, besides, she really did not feel the cold much. At six o’clock she closed the shop by turning the key in the door, and took up her work again. She could hardly see it. She was angry with herself for having cried about the toffy-apples.

The church bell tolled. It was Tuesday, and in the ordinary way there would be no service that night; she could not understand it. The second stroke came a long time after the first, the third at an equal interval. It was the passing bell. All at once Miss Nulty understood. He was dead.

At first the knowledge did not increase her pain; it seemed to bring them closer together again, and make it possible for her to think of him more freely than she had dared to allow herself to think before. But very soon the terrible difference between dead and living struck her with a hopeless perplexity, and the thought that now there would be no use in making the toffy-apples filled her with desolation. It was too late to do the one small thing for him which she might have done if he had lived another day.

She put fingers to her ears to shut out the tolling of the bell. Then, mechanically, she went on with her work, not daring either to give it up or to put on her bonnet and go to see the dead man’s wife. She had not seen him since the day he had been stricken down; all her news came through Lisbeth, who never suspected that there had ever been anything between the two. Lisbeth was never particularly bright-witted.

Instead of going upstairs as usual after closing-time, Miss Nulty stayed in the shop; it somehow seemed more familiar and warmer than her barely-furnished bedroom. Indeed, when the clock struck ten, she found that she was afraid to go up alone; not because of ghosts or any nonsense of that sort, but because she could not face the loneliness that awaited her at the top of the dark staircase. Then she remembered the two or three letters which he had once written to her—they were upstairs, hidden away at the bottom of an old tin box, which contained some of the things she had secretly prepared for the wedding that never came. She had so strong a fancy to see the letters again that her fear slipped into the background. Just as she rose, a hurried tapping sounded on the door. She unlocked it to admit Lisbeth.

“You’ve heard, I s’pose, Mary?”

“I heard the bell, Lisbeth.”

Lisbeth sat down and rocked herself to and fro; she was pale, and her eyelids were a little swollen from crying, but she was now perfectly calm.

“He went quite sudden, an hour after I got home.”

“Poor soul. I’m sorry, Lisbeth. There! don’t take on.”

Mary felt that she was trembling, and had an almost irresistible impulse to cry out. She threw her arms round Lisbeth’s neck, and kissed her eagerly.

“Did he die happy?” she asked.

“Just the same as goin’ asleep. I wouldn’t have come to you to-night, only there’s somethin’ I must tell at once. He must have his last wish, though it was a strange one.”

“What was it, Lisbeth?” She just breathed the question.

“‘Let Mary,’ he said, ‘let Mary make my shroud.’”1A cloth used to cover a person’s body for burial.

Miss Nulty said nothing; she stared straight before her with a feeling that if she moved her secret would leap out in spite of her.

“I knew you’d think it strange—but there! If some one else made it, he’d never know, and p’raps ’tis too much for you.”

“No, no!” Mary cried, “I’ll be glad to make it; I’m proud he thought of me.”

“He always spoke well of you.”

“That was real good of him, Lisbeth.”

“You’ll set about makin’ it at once?”

“Surely I’ll do that.”

“I must be gettin’ back now. Oh, I was forgettin’ to give you the measurements.”

Lisbeth handed Miss Nulty a slip of paper, and went away after a consolatory embrace. When the door was locked again, Mary felt happier than she had done for years. He had remembered her at the last, he had thought of her, and not of Lisbeth. She experienced a pitiful joy that called for tears, but she restrained them because all her strength, both of body and sight would be required to do the great work.

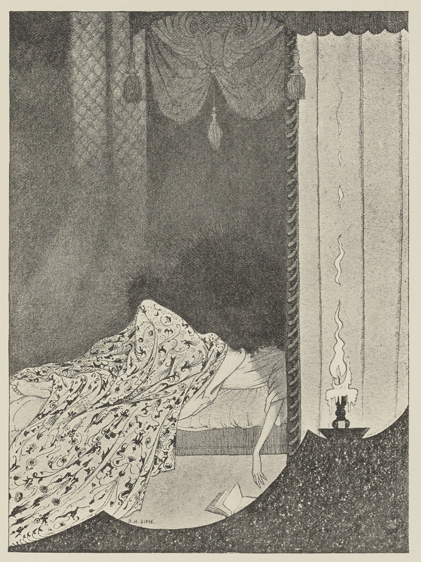

She went upstairs boldly, and opened the box which had not been unlocked for so long. From it she took a roll of linen, fine, and a little toned by age; it had been laid in against her marriage. This she took downstairs, and, having cleared her little counter, set to work at once.

Hour after hour she toiled, putting her soul into the neatness and fineness of the stitches, recapturing a hint of the glamour of her youth in performing that last office for the dead. She felt no weariness, only a passionate desire to make it the most perfect piece of work she had ever done; her eyes seemed to help her strangely; she saw quite clearly again, even by the indifferent aid of her small oil-lamp.

When dawn came she was still at work. At eight o’clock she did not open the shop for fear a customer might come in and interrupt her. The news that Miss Nulty was making the shroud soon got abroad, and every now and then a passer-by would stop and stare in through the window. She took heed of nothing; she simply stitched on.

Late in the afternoon the shroud was finished, and she took it round to Lisbeth. With awe and a yearning swelling of the heart, she looked upon the dead man’s face.

“You get cleverer and cleverer, Mary,” said Lisbeth; “every stitch is a wonder.”

“He’d a fancy for me to make it, and of course I done my best.”

“Ah, yes! for sure you did.”

“He’d a taste for pretty things.”

“Yes, he were main fond of anythin’ nice to eat or drink or look at.”

Neither of the women realised that the man had been a mere lump of selfishness, unworthy of the love of either.

When Miss Nulty got back to the shop it was closing time, so she turned the key behind her.

Word Count: 2759

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Charles Kennett Burrow. “The Shroud.” The Butterfly, vol. 1, 1899, pp. 203-14. Edited by Emma Poulsen. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 7 February 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/4929/.

Editors

Emma Poulsen

Rachel Jones

Elizabeth Etherington

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

10 March 2025

Last modified

6 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | A cloth used to cover a person’s body for burial. |

|---|