Lucy Norcott; or, The Wife at Home

by M. A. R.

The British Workwoman, vol. 4, issue 120 (1864)

Pages 26-27

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “Lucy Norcott; or, The Wife at Home” is a short story addressing the social taboos of working women during the Victorian Era. Agnes, in search of a housemaid, visits the thriving family of a homemaker wife who is glorified in her duty as wife and mother. By contrast, Agnes also encounters a family whose mother has left home to work, and she is blamed for her family’s destitution.

The story conveys a cautionary tale for wives and mothers as it explores the consequences of social systems that entrap families in cycles of poverty.

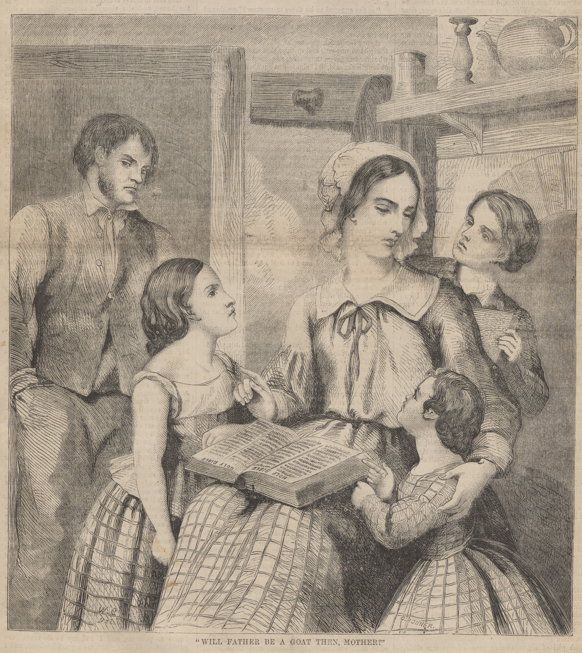

A PONY carriage stopped at the gate of a neat little garden in the village of Ferndene, and before a little boy who was playing there could call his mother, a young lady had jumped out and entered the cottage. She kissed the smiling young woman who met her at the door, for Lucy Norcott had been her nurse, and then, while taking the seat which was offered to her, she said, “I am in a great hurry, Lucy, but I am come to ask if you would just help us a little at the hall. The housemaids have both been sent away, and we sadly want somebody who knows about the house, to come and help. Will you come, just this once, dear good Lucy?”

But, dear, good Lucy knew her duty better. She said she was sorry, very sorry, not to oblige those for whom she had so great a respect, but that her first duty was at home.

“But just for once,” urged the young lady. “Your neighbor could take charge of the children, and you could lock up the house all safe.”

“And what is my husband to do when he comes home for his dinner, and finds the house empty, and his door locked against him?” asked Lucy, smiling.

“O, let him take his dinner with him in the morning,” quickly said Miss Alstone.

“My dear young lady,” said Lucy, and now she spoke gravely, though in a gentle voice, “my first duty is to my husband and children. To keep his home such an one as he can love to return to after his daily labour, and to give my little ones that care which none but a mother can give; this is what I am bound to consider, above everything else in the world.”

“But think how nice it would be to add to your husband’s earnings,” again urged the young lady. “It must surely be always good to increase your income, Lucy.”

“William’s wages are enough for us, dear Miss Agnes, and there would be no saving, but rather loss, by my going out.”

“How so?” asked Agnes, surprised.

“Why, of course, my neighbour would not be troubled with the children for nothing; even if I did not pay her money, I must provide food enough for the children and for her too. Then cold meat and dry bread, which William would be obliged to take for his dinner, cost more than any little warm mess I can make for him here. So indeed I must not leave my home.”

Agnes looked vexed; what more could she say? But she was not going to be beaten yet, so she pleaded, “But do not labouring men often dine on cold meat and bread, even if they do come home?”

“Yes, Miss Agnes, certainly they do, but it is bad economy. I can warm up a little meat with potatoes and onions, or any other vegetable, and perhaps rice or flour, and make a little go much farther than if he ate it cold with bread. And then the children, if I give them dry bread and meat, they never seem satisfied, neither do they relish it; but when all is hot and savoury, you cannot think how they enjoy their dinner.”

“Well, they seem to thrive upon it, certainly,” said Agnes; “so you really are determined not to come? And I suppose I must own you are right, as you always are, Lucy. So I must go and tell mamma that I have failed.”

She rose to go, but at the door she stopped and said, “But can you recommend to us any woman who is accustomed to go out?”

Lucy reflected a moment, then said, “Yes, there is Mrs. Johnson in the house next door to the ‘Bell’. I know she goes to several families.”

“Is she honest?” asked Agnes.

“I know nothing against her honesty; she seems clean and hardworking, by the accounts I have heard of her.”

“Then good bye, Lucy; good bye, little ones, I must go and try Mrs. Johnson; but she won’t be like you, Lucy,” she added affectionately.

Now Lucy’s little room, more like a parlour than a kitchen—for all washing and messing works were done in her scullery at the back of the house—was a picture of neatness, but the room at the door of which Agnes now tapped with her lively fingers, presented a striking contrast.

On a childish voice answering, “Come in,” Agnes entered.

A girl of about twelve years of age was sitting beside the fire, rocking herself backwards and forwards in the vain attempt to stifle the cries of a sickly looking baby, which looked as if it had never ceased wailing since first it came into this world. Another child, scarcely able to walk, was standing near her with a piece of bread and treacle in its hands, more treacle being visible on the face, hands, and pinafore, than on the bread itself. Two others were in the room, sprawling idly on the floor, playing with a broken toy.

The young lady hesitated a moment, but by this time the girl had risen, and was standing staring at her in a manner which expressed stupidity rather than rudeness.

“Is your mother at home, my girl?”

“No, but she’ll be home late; do you want her, please Miss?”

Agnes hesitated, the cottage looked so miserable, the girl so uncouth and untidy, that she felt doubtful whether to engage the mother to come to the hall, but at length she said, “If she is not engaged to-morrow, perhaps she could come and speak to my mamma in the morning. Will you ask her to do so?”

“Yes, I won’t forget,” answered the girl, still shaking the poor baby, so that its plaintive whine came out by fits and starts. “We’re poor enough, and mother has to work hard,” she added, in a mournful tone.

“How is it that you are so poor?” asked Agnes, kindly. “Has your father no work?”

“Oh, yes, Miss, he gets work regular enough, but if it war’nt for mother, we should all be starved; poor mother slaves herself to death to keep us all.”

Agnes felt distressed; she was very young, and had yet to learn the secret of the poverty of the labouring man who has plenty of work; so she only remarked the sorrowful look on the girl’s face, and the general appearance of discomfort in the whole family. She felt unwilling to go and leave them without a few kind words. So she said gently,

“That poor baby seems ill.”

“She’s always cross and fretful-like,” replied the girl. “I never can keep her quiet. You see, Miss, mother had to go out to work, when baby was only five weeks old, and I have to feed her as well as I can, for she only gets to mother at nights, and the neighbours say the bread and water does’nt agree with her.”

“Poor little one,” said Agnes, compassionately; “I will ask mamma for some arrowroot for her. But now I must go. Do not forget to send your mother to us to-morrow.”

The girl promised, and the young lady returned home.

After hearing her daughter’s account of her visit to the cottage, Mrs. Alstone ascertained that the woman Johnson was an honest hard-working person, who did really as her girl had said, “slave her life out” to provide for her family; but that the husband was a drunken fellow, who spent the greater part of his money at the public-house.

So the next day Mrs. Johnson was engaged to help in the house till the new servants should arrive.

Mrs. Alstone was kind-hearted and liberal, and many nice scraps from her table did she give to the poor charwoman to take home to her family, and two or three different kinds of food for the baby were carried thither by Agnes; but the poor girl, Susan, who tended the baby as well as she could, knew not how to make these messes nice, and soft, and warm, so the baby throve no better on them than it had done before. Yet the careworn, haggard-looking woman, her own clothes often ragged, and her appearance dirty, worked hard, and swept, and scrubbed, and was always civil and obliging, so what more could be done? She had no time to mend her clothes, for often it was late ere, weary to death, she walked the two miles to her home, and then she had frequently to endure abuse from her drunken husband, who would come in out of temper, just as she was about to creep into her ill-made bed, with the wailing baby in her arms. Then the poor babe would tug and tug, and get from her the tired unwholesome milk which had been kept unnaturally for hours, and which, while it exhausted the already overworn mother, only served to cause suffering in the infant, whose wailings never ceased excepting when it slept, which was only at short intervals; and then in the morning, weary with want of rest, the mother would rise to walk off again to her daily labours.

Now all this was very pitiable, but let us not talk of it as if such sufferings as these were the allotted portion of the poor, or of the family of the working man. No, here, as in most other cases, an acquaintance with what Lucy Norcott had justly called her “first duty,” would, in all probability, have saved poor Mrs. Johnson all her unhappiness. Her husband and William Norcott received precisely the same wages, eighteen shillings a week; and when Mary first married, their little dwelling was furnished out of her savings, and was as comfortable a cottage as you would wish to see.

Mary, too, had neat clothes. She had been servant in a gentleman’s family; and her wedding dress, as well as sundry useful articles, had been given her by her mistress and her daughters.

But Mary was not contented with eighteen shillings a week.

Her late mistress asked her to come in and help in the house, and she thought one-and-sixpence a day was not a thing to refuse; so she had not been married three months before she began to leave her home almost as early as her husband, and return at night even after the hour at which he left off work.

On these occasions the house must, of course, be locked up, and a cold dinner (often bread and cheese, for Mary had had no time to prepare any food the day before), was tied up in a handkerchief for Johnson to eat as he could by the road-side. And then, when evening came, with his wife still absent, what could the poor man do, but step into the warm, snug parlour of the “Bell,” and wait there for her return?”

Johnson had not been otherwise than steady when he married—he was not a total abstainer; indeed he fancied that he could not work so well if he had not a pint of beer daily; but he had been courting Mary for some years, and had kept himself sober for her sake. But now, the landlord of the “Bell” would have taken it ill if he had sat in his parlour and drank nothing; so, though he had had his pint at dinner, another and another were taken, till by the time his first child was born, Johnson had become an habitual drunkard. Hard was the struggle, oftentimes, for the poor wife to get money from him to pay their rent, and keep her and the babe from starving; and before she had quite recovered her strength, Mrs. Johnson left the baby with a neighbour, and went out to work as before.

And this had now gone on, till, as we have seen, their eldest girl was twelve years old, and there were three others to feed and clothe, several having died in their infancy for want of their mother’s care; and the last appearing as if it had come into the world only to suffer. Mary Johnson was nearly the same age with Lucy Norcott, yet, with her haggard looks, her sunken eyes, and dead brown complexion, she looked nearly twenty years her senior.

Lucy, though she had not married until she was twenty-seven years of age, still retained the fresh look of her youth. Her colour was bright and healthy, her eyes clear, her step light; and, though her rounded form proclaimed her a matron, you would never guess that she had passed her three-and-thirtieth birthday. Her three children were healthy and strong, for they had been blessed with good constitutions; and, as she had never confided them to another’s care, they had always been kindly and judiciously treated.

Lucy rose in the morning a little before her husband, in order to have a warm breakfast to give him before he set out to work; and when he came down, refreshed by his sleep in the clean and well-aired bed-room, he found everything neat and ready, and his careful wife, with her loving smile, to greet him,

Their babies, being healthy, soon learned to lie or crawl upon a clean cloth spread upon the floor, so that the mother could finish her work undisturbed, and be ready to take up the little one, ere it grew tired of amusing itself.

She had watched the cook during her period of service, and taken from her many a useful hint, which she now turned to good account; and thus she contrived, as she had told Miss Alstone, to make a little meat, well cooked, and mixed with vegetables or rice, form most inviting dinners, to which her husband sat down with pleasure. The table-cloth was always clean, so were the plates and cups; and the jug of fresh spring water looked so refreshingly cool, that William never thought of wishing for beer.

“The money that beer would cost pays the rent,” he would say; “and my Lucy shall never know want because I drink her rent away.”

How could any of this have been done, if Lucy, like her neighbour, had gone from home to work? Her children must have been neglected, and her husband driven from his home. “God has given me duties to perform, and I will try to do them,” she would say. “He has given me a good husband, and I will make him happy in every way I can.” And with this view, simply and constantly before her, Lucy contrived to do all her washing and cleaning between the time of her husband’s going out in the morning and his return for dinner; and he was, perhaps, the only man in the village who never knew what it was to have a washing-day. And thus, with their eighteen shillings a week, the Norcotts were rich.

Lately there had been a small but weekly increasing sum in the Post-Office Savings’ Bank, ready against a rainy day, sickness, or want of work, or old age and its infirmities. Sometimes envious neighbours would wonder at the appearance of plenty and comfort in those whose position was the same with their own; and some even went so far as to say, that there must be a means of obtaining money of which they knew nothing. Perhaps the landlord of the “Bell” could have told them, that one great cause of this prosperity was there being no customers of his; but he held his peace, and only wished in his heart that Mrs. Norcott would take to going out to work.

But let us return to Mrs. Johnson. It is Saturday night, and she has been out at work all the week, “gaining,” as she calls it, eighteenpence a day.

But when she comes home, three shillings of her hard earnings must go for rent, or they will be turned out of their house, for their landlord, knowing the character of Johnson, is strict in enforcing the weekly payment. Then the baker has let poor Susan have bread for the family all the week; for dry bread, with a little rancid butter, or dripping, has been all they have had to live on, and nearly four shillings go for bread. Coals, too, are dear, and children never know how to save in firing, so, many more are consumed every week, than need be if the mother had been at home; and thus all poor Mary’s earnings are gone at once, spent, as it were, before she receives them; while for tea or candles, or any little needful groceries, as well as clothing and shoes for herself and the children, there is nothing but what she can beg from her husband, and it is a small sum indeed which he brings home on Saturdays. He has always a score at the “Bell,” and while he pays that, he must drink again, for he knows that Saturday night is the time when his worn-out wife is doing the week’s washing, and there is no room for him at home, even though she is come in; so he sits drinking on, drinking away the lives of his wife and children, and most certainly drinking away his own; because the wife, whom he once loved so well, has been ignorant of her duty, and made his home miserable.

And when Sunday comes, where are the Sunday clothes? Mary’s have been pawned long ago, to procure food for her babes, and the poor children never had any,—they scramble through the holy Sabbath-day, as they do through others, dirty, hungry, cross, and sickly. Even Susan cannot read; for ever since she was seven years old, she has had the charge of the younger ones, and no Sunday-school teacher has had an opportunity of leading her to the knowledge of her Maker and Redeemer. She is growing up as ignorant as she is miserable.

And when that girl is older, how will she pass her time? Will years of themselves bring wisdom, and will she learn to keep the house as her mother should have done? No. The habits of idleness, and dirt, and improvidence, of her early days will cling to her; she will stand in the doorway watching the passers by, or joining in idle, perhaps sinful conversation; and never having been taught to distinguish right from wrong, her conscience will become hardened, and her career will probably be one of sin and shame. Poor girl! Is it her mother’s ignorance of her duty that shall lay her thus low? Had the mother kept her home like Lucy Norcott, Susan might early have attended the village school, and, being taught habits of neatness at home, might have become a valued servant in a gentleman’s family, till, in her turn, she had taken upon herself the holy duties of a wife.

Oh, mothers, if not for yourself, yet for the sake of your yet innocent children, stay at home, and help to fit them for the duties of life, as none but a mother can.

One Monday morning, Norcott happened to overtake his neighbour Johnson on his way to work. There was little in common between the two men, and Norcott had long felt shy of his drunken acquaintance; yet there was something in Johnson’s appearance to-day which induced him to slacken his pace, that he might speak a few words before passing on.

Johnson’s step was unsteady, his back was bent like an old man’s, his face was purple and bloated, and his voice husky, as he replied to Norcott’s kindly salutation.

“Aye, good morning,” he said, gloomily, “the morning’s always good with you; you look as fresh as an apple, and as clean as if you were going to church; I wish I was as rich as you are.”

“And why are you not?” asked Norcott, “our wages are the same.”

“Aye, but you have got a clever managing wife, who knows how to manage everything, and she makes your home comfortable.”

“Johnson,” replied his neighbour, gravely, “if you did as I do, give all your wages into your wife’s hands every Saturday night, you might be as well off as we are.”

“A pretty thing, indeed ! And what am I to do for a drop of beer, I should like to know? The ‘Bell’s’ the only place where I can have a moment’s comfort, and how can I help going there?”

“Cannot you bid your wife stay at home and make things comfortable?” urged Norcott. “It seems to me that her going out has done all the mischief.”

“It drove me first to the ‘Bell,’ and that’s true,” replied Johnson, bitterly; “but now I’ve got the habit of it, I can’t live without it, and my wife says we should all be starved if she did not work; and Sukey’s a big girl now, and able to manage at home.”

“And how does she manage, poor child?” returned Norcott, “but by lolling all day at the door, and gossiping. Why she cannot even do up the house fit to be seen, nor wash the clothes; and how should she, when her mother never taught her?”

“Well, well, man, that’s all very fine, but poor folks must work and slave, and get on as they can, and not interfere with each other, that’s what I am thinking.” And Johnson looked so inclined to quarrel with Norcott, that he ceased from his well-meant remarks, and merely bidding him good-morning again, went on his way at the brisk pace which was natural to him.

“What a happy thing it is for me, that, from the first, we determined that Lucy should never leave her home,” he said to himself. “I might have been driven to the public-house like that poor fellow, for want of a home, and have been what he is, a poor, wretched, miserable drunkard. Oh, what mercy has followed me,” he exclaimed soon after, “what a mercy that my Lucy knew her duty, and was determined to do it! I do not believe poor Mrs. Johnson has an idea, to this day, that all her misery is her own doing. And many other people err through ignorance, I believe. They think only of earning money, and never reflect how much they lose by it; money, health, character, happiness. Would they be wiser, I wonder, if they did know it; if every wife and mother said, as my Lucy does, that her first duty is to her husband and children? Some women like gadding about into gentlemen’s houses, or even those horrid laundries, where they can gossip all day, and get gin to drink; yet, perhaps, even some of those might never have begun the bad habit, if they had known the misery and poverty which are sure to follow it.”

So William Norcott went in, debating with himself this anxious question, till he arrived at the farm where he worked.

Wife of the labouring man! Take warning in time. Try to make home happy to your husband and children. Remember your first earthly duty, and, whatever be the temptations to go out to work,

STAY AT HOME!

Word Count: 4034

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Elizabeth Goss

Kayla Williams

Alissa Merrill

Posted

10 March 2025

Last modified

6 May 2025

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.