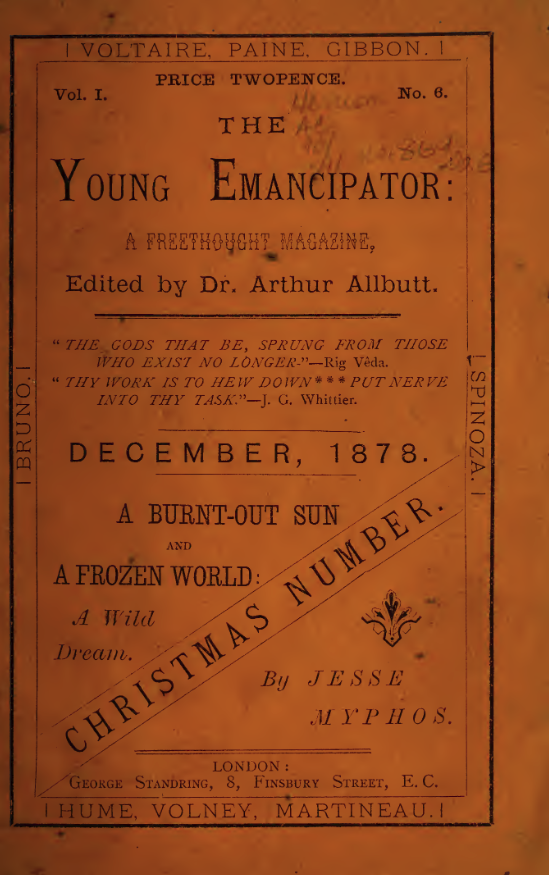

A Burnt-Out Sun and a Frozen World: A Wild Dream

by Jesse Myphos

The Young Emancipator, vol. 1, issue 6 (1878)

Pages 121-143

Introductory Note: This apocalyptic science fiction tale was featured in a special Christmas edition of The Young Emancipator, a magazine intended for the children of Secularists of all classes. The publication’s goal was to free the rising generation from religious influences through instruction and entertainment based on Secularist values. The story speculates on rational, scientific causes for the end of the world, which Secularist parents may have preferred as an alternative to apocalypse narratives their children might hear from religious sources.

Advisory: This story briefly discusses suicide.

SOME years ago—how many is of little consequence—I was in South America, engaged in mercantile transactions. It will not be necessary to name the town in which I took up my residence; suffice it to say that it was near the Pacific Coast, and within sight of some of the loftiest peaks of the Andes. There I remained for many months, during which I had the pleasure, or otherwise, of feeling more than once the sensations produced by an earthquake. It would not much interest the reader to be told how I spent my time in that distant land, or whether my business transactions proved lucrative or not: my sole reason for mentioning the fact that I ever was in South America at all, is merely to introduce the following singular and terrible story.

One beautiful Summer day I had nothing particular to do, having finished my business and packed up my things preparatory to returning home. To pass the time I took a stroll along a secluded path, where I could see the tall snow-clad mountains on the right, and on my left the sparkling rippling waters, flashing with myriads of fitful gleams of light, far over the Pacific. The scene was every way enchanting, and I sat down to enjoy it, casting alternate looks to the mountains and the ocean. I was alone; and the quiet, monotonous loveliness of Nature, especially on a hot day in or near the tropics, is apt to make a spectator drowsy, unless he has something particular to fill his thoughts or attract his attention. In my case external Nature, though dressed in her most bewitching apparel, proved far too weak to cope with that nature within, which impelled me to sleep. I do not remember to have struggled at all against my fate—sleep demanded me as a victim, and I yielded without a murmur or a sigh.

How long I had been wrapped in slumber I, of course cannot say, as sleep and dreams know nothing of the flight of time; but it seemed as if I had scarcely closed my eyes before the vision I have to recount appeared. It seems to have been waiting for sleep to put me within its power, and no sooner did it see its advantage than I was pounced upon, and led captive at its pleasure. I have called my dream a vision, for such it was—all that I am going to relate I saw and heard with such intense realism, that everything I ever experienced when awake seems dreamy and unreal, in comparison with what was burnt in upon the substance of my being during that sleep. The reason may be this: Everything we receive through the senses is sifted, so to speak, like the sun-light coming down through a fog; but a vision falls with all its fervency upon the sensorium, without any sifting whatever from the clear sky of the inner world.

However, let the vision speak for itself. As soon as I was asleep, so it seems, an old man, older in appearance than anyone I had ever before seen, came up to me. His body was very thin, his fingers long and bony, and the nails seemed as if they had not been pared for a generation or so. His long lank hair was white as the snow upon the peaks of the Andes; his face furrowed deeply with age and anguish, and his complexion darkened by exposure to the weather. In his eyes there glowed a wild frenzy, and his appearance denoted the maniac. Still his bearing was not without dignity; his brow was lofty and noble, and in his air there were manifest the fragments of a shattered majesty that had once been natural to the man.

There was no doubt of his insanity; but I soon found that there were intervals of perfect composure, during which his maniacy was kept in thorough check, and his bright intelligence shone with its true splendour. He came up to me as I sat—so it seemed in my dream—beneath a withered stump of a tree, in the midst of a vast plain covered with frost and snow. The cold made me shiver horribly; and from the quantities of ice, and the dim light that gave every object a sort of spectral appearance, I began to fancy myself in the neighbourhood of one of the earth’s poles. As soon as my strange visitant saw me, he halted, as if under the influence of sudden fright, and gazed at me for some moments in speechless wonder. He next began to laugh hysterically, and shout in a most boisterous manner. Then, turning to me, and looking full in my face he cried,

“Oh! Oh! I thought they were all gone. Oh! Oh! I thought I was all alone by this time. I have been all over the world and back, and you are the first man I have seen for such a long time. I thought I was alone on the wreck now, and that my turn was nearly come.”

“Wreck” I replied, “Have you been shipwrecked, friend?”

“Shipwrecks! plenty of shipwrecks,” returned the old man, “more than I could count. But, dear me!” he continued, “how startled I was to see you! I thought I had the world all to myself. All to myself,” he mused, repeating the expression again and again. Then turning abruptly to me he said,

“Don’t you know me?”

“No!” said I, “I never saw you before.”

At this he started up from the stone on which he had sat down, and with the wildest gesticulation, he shouted fiercely,1In the original, the paragraph begins with a quotation mark.

“What! don’t you know Toti Patoo, the greatest astronomer that ever lived? the man who discovered the moon’s atmosphere, and found out that Mars and Venus were both inhabited!”

“No,” I replied, respectfully, “I never heard of the astronomer you mention, nor yet of his grand discoveries, till this very moment.”

At this he began to laugh, and then frantically walked up and down for some time. By-and-by he again turned to me with a most puzzled look, and said,

“Do you mean to say that you never did hear of me and my discoveries? Where can you have lived all your life?”

“Most of my time,” I replied, “has been spent in England, my native country.”

I never saw such a look of wonder as came over the old man’s face as I made this reply. He evidently thought I had lost my reason; and there we were, looking intensely and inquiringly into one another’s eyes, each feeling confident that his fellow was hopelessly insane. At length he slowly retorted,

“You must be very, VERY old, if you lived in old England. The name has not been much heard in my day; though I remember well to have read of her glory and renown; and had not worse things driven it out of my mind I have no doubt I should still have some vivid conception of her tragic doom.”

For a moment or two I looked at my companion with breathless wonder, and at length exclaimed,

“Tragic doom! What! What do you mean?”

“Mean?” he replied, “Why, England, as I well remember reading in history, was overthrown by an earthquake, and completely expunged from the map of the world by a sudden subsidence of the land, in the year A. D. 2,587.”

“Two thousand five hundred and eighty seven,” mused I, “you must be dreaming, my friend; we are now living in Anno Domini 186—, that is more than 700 years before the date at which you say that England was destroyed.”

“Dreaming! dreaming!” he exclaimed, wringing his hands, and tearing his hair in the most frantic manner, “Oh, that my life would turn out to be a dream! God knows it would be most horrible, even then. But it has been no dream! no dream or awful vision, woven by madness. I am mad,” he continued, “but it is my sufferings that have made me so. What I have seen and suffered would drive a god mad. Yes! I am mad; but madness has been no refuge from suffering. I know it all! There has been no oblivion for me! Would that I had died in the destruction of the world!”

“Destruction of the world!” exclaimed I, interrupting him, “How! are we not now living in the world? How can you talk of the destruction of the world?”

I felt profoundly agitated, and knew not what to make of it all. The old astronomer was terribly earnest, and though mad for certain, did not seem to be possessed by a false and distorted vision of things; his was the madness that fully comprehended the situation—a madness belonging far more to the heart than the intellect. As I perceived later on, his insanity was but the reproduction of the dreadful catastrophes he had seen Nature undergo, and the horrible confusion that had surrounded him for so many months. Nature first went mad, and her most unfortunate child was driven perforce along the same wild path. Nature committed suicide: her child saw the deed, and comprehending its awful meaning, went mad. Such reflections seem to have passed through my own mind while listening to the astronomer’s tale. But it is time I gave the tale itself.

“I know you think me mad,” resumed my friend, “but listen, you don’t know anything about the end of the world, you say; well, you must, I think be an inhabitant of some other world come to visit this ruined globe, perhaps to relate to others far away the fate of that planet where once dwelt the race of Man. I’ll tell you how it happened; I saw it all from beginning to end. Will you hear me?”

I had no choice in the matter. Listen I must, for the old man had already entranced me, and his spell was irresistible. I felt bewildered. I could not shake off my own identity, nor persuade myself that what I remembered of my life and associations was all a dream. Then on the other side was the seeming reality of present experience: how could I doubt that the man before me was a real being? So true did the dream appear, that at times I was more than half inclined to think that my life was the dream and the dream the reality.2Original text reads “then” instead of “than.” But perplexed though I was, I was eager to hear the old man’s tale, and when he asked if I would listen, I replied,

“Yes! tell me the whole story.”

He thereupon sat down on a frozen stone directly in front of me, and looking full into my face, thus began:

“As I told you just now, I was an astronomer, the chief astronomer, in fact, in the large Republic of Parawangaroo. My observatory was built on a moderate sized hill not far from the City of Congoora. I was very famous all over the world; but you never heard of me, eh? Ha! Ha! Ha! Never heard of Toti Patoo.”3The original had no punctuation at the end of this sentence. This he said in a most excited manner; but in a few seconds he again calmly took up the thread of his narrative, apparently quite unconscious that he had broken it off—“I loved astronomy and devoted to it all my powers. The sun I made my especial study, and mastered and classified all the phenomena exhibited by that luminary. Well, about a week before the earthquake that rent South America in twain, and swamped the West Indies, I—”

“South America in twain! West Indies swamped!” cried I in the most violent agitation, “Why—when did that happen? I am in South America now, am I not?”

At this outburst of mine the old man laughed again, and bestowed upon me a look which said as plain as words, “you must be insane.” At length he said,

“We are not in South America, but in the Republic of Parawangaroo, that was on the Continent of Boromango, near the centre of the Pacific. And, as I was saying, when you interrupted me, about a week before that earthquake I observed several enormous spot-clusters on the face of the sun, and by means of the spectroscope I also saw that the sun’s photosphere was in a state of the most violent agitation, far more tremendous storms being raging there than any on record. Not many hours had passed before the earth was bombarded by meteorites, which fell in showers.4Original text does not include a space between “by meteorites.” Many of them were of enormous size, and they continued to fall for two or three days without intermission. Great numbers of people were killed, and my observatory was knocked to atoms by an aërolite of about 1,000 lbs. weight. I wish I had been dashed to pieces too by the same stone! I never should have been mad then! Never seen the end of the world!”

I made no reply; and after a brief pause the astronomer went on:

“Out on the ocean too, frightful damage was done, and a great many ships were sunk with all their crews. The worse case of the kind was the loss of the Priapooloo, of 100,000 tons burthen, and carrying at the time 5,000 passengers. A large meteorite struck the vessel and knocked her in two pieces. Only eight or ten persons escaped with their lives. Pshaw! That’s nothing!” said the old man, as he saw my look of horror at his recital, “these are mere trifles that I am telling you now.”

“As I said, there was an earthquake, the greatest ever known. It occurred on the 18th of June, A.D. 5,010, and passed right through South America longitudinally, pushing the western half of the Continent some miles out into the Pacific, and tilting up the eastern half in such a manner as to form a range of high mountains along the western edge of the section, and to sink a large strip of the eastern shore of the Continent thousands of feet under the Atlantic. The whole Continent was a wreck: nowhere was a piece 20 miles square left whole. Through the chasm made by the earthquake the ocean waters rolled, forming the longest strait in the world, and known afterwards as the Earthquake Channel. There were about 1,000,000,000 of people in South America before the catastrophe, but when it was over not one tenth of that number could be found.

“The effects were powerfully felt also in political and commercial matters. Several whole nations disappeared entirely, and others were nations no longer. A famine and commercial disorganization ensued, and sickness assisted the long dearth to decimate the wretched people who survived. But the destruction was not confined to South America. The West Indies, to a rock, disappeared, and Central America, from Panama to the City of Mexico, shared the same fate. Terrible business, no doubt, but I only wish I had gone down or been ground to powder along with the victims of that earthquake. Their fate was Paradise compared with what mine has been. But regrets are useless; and besides it is nearly all over now.

“In a few years the world went on again much the same as before. Every nation suffered more or less, if not from the earthquake, at least from the showers of meteorites. But the elasticity of humanity soon restored the old race of progress and prosperity. It is wonderful how soon the calamities were forgotten, and how peacefully the world went on its way. My observatory was soon re-built for me, and I once more began my favourite studies and observations. The sun was now become an object of greater interest than ever, and of course I was curious to discover whether he differed at all from his former self, after the terrible cannonade he had given us. But I saw very little difference: the great luminary went shining on as before, as if too exalted to consider the possibility of doing injury or otherwise to so small and distant a spec as the earth.

“I need not recount the doings of the few years that remained—they were uneventful, and most of the time was spent in peace and plenty, at least by me and mine. Whatever fears I may have entertained of an approaching cosmic cataclysm were gradually dispelled by observing that nature had resumed her old composure, and was quietly running her accustomed race. Man,” he continued, turning to me, “depends upon Nature for everything. He is—I mean he was, part of the great whole; too insignificant to mould or sway the whole, he was borne irresistibly along whatever path Nature happened to take; when her course was smooth and prosperous things went well with him; but when Nature became agitated or convulsed, Man partook of her terrible paroxysms, and became utterly demoralized. But I am forestalling.

“About five years after the earthquake, on a beautiful day in summer. I turned a large telescope upon the sun, and for some time carefully scrutinized his face. It was about eight o’clock in the morning when I began my work, and the power I used was one magnifying 1,000, which showed up the details of the sun’s surface with charming perfection. The atmosphere was unusually pure and quiet, and the definition given by my instrument was surpassingly sharp and distinct. Besides a larger number than usual of sun-torches, or faculæ, there were several good clusters of spots, in the study of which I soon became deeply absorbed. Round about one of the spots there was a ridge of intensely bright light, much larger and far more brilliant than anything of the kind I had ever before seen. While I was looking at it the ridge of light began to rotate and sway to and fro in a most extraordinary manner.

“This was all I had time to observe: the next moment I was completely blinded by a sudden inrush of light into the telescope. I started away from the instrument, and for some seconds was unable to see anything; and the overpowering heat that flooded the observatory sent me reeling away to find shelter wherever I might. As soon as my sight returned I perceived that the whole earth, as far as I could see was deluged with light tenfold stronger than that of a tropical noonday sun. The rocks and mountains, the houses and streets—yea, the very meadows—glowed with surpassing splendour; and as I saw it, I felt sure it was the earth’s funeral torch, lighting her and her children to the grave. I at once guessed what had happened; for I had seen many a distant sun blaze out in sudden glory for a few weeks, and then fade away into primæval darkness. Astronomers of both ancient and modern times had hinted again and again that our own sun might some day take fire and scorch the earth to a cinder, and afterwards go out like an exhausted lamp.

“They had suggested the possibility of that terrible catastrophe; but they all had the happiness of retiring to rest while the course of Nature ran smoothly. I, however, most unfortunate of my kind! have remained above ground long enough to behold the conflagration they had merely speculated upon. Whenever I had watched a burning sun in the far off firmament I had regarded it merely as an event of astronomical interest, and never once thought of the calamity it might be inflicting upon the myriads of sentient beings that might previously have been spending a joyous existence in the planet worlds that rolled around that burning sun. When I turned my spectroscope upon the magnificent orb, and watched with keenest ecstasy the spectrum that told me what metals and gases were burning in that distant sphere, I never once thought of the millions of miserable wretches who at that moment were roasting in its terrible blaze. But community of woe, for a time at least, gives oneness of interest, and now, when my own sun was on fire, I thought with a pang of those who had before now perished in similar conflagrations.

“I now also pictured to myself some astronomer dwelling on some planet revolving round Sirius, Rigel, Regulus, or Capella, who had been accustomed to see our sun as a faint spec of light in one of the constellations of his heavens, now having his attention attracted by its increased brilliancy as it rose from the tenth, or fourteenth, magnitude to the first, and then sitting down to his instrument to watch the phenomenon—while the poor wretches who had drawn their life and bliss from that very sun were roasting in the torrid heat!”

“Bah!” said he, suddenly, “what is the use of sentiment!” For a few moments he sat in silence, with his hands pressing his head, and his elbows on his knees, after which he resumed his story.

“Not far from where I lived there was an enormous cave in the heart of a mountain, known as the Hunter’s Cavern. How large the cavern was no one knew, as it was found impossible to explore the whole of it. Probably it extended for several miles; and tradition said that a party which once set out to explore its furthest recesses had never returned, nor could any traces of them be found.

“As soon as night came on on that memorable day, and the heat was at all bearable, I got some provisions packed up, and removed with my wife and family to the Hunter’s Cavern. I found on our arrival that a large number of my neighbours had preceded me, but thousands of others, I was told, had been literally frightened to death by the sudden and overwhelming flood of heat and light that had just fallen upon the world. Multitudes of others were so paralysed by terror that they had no heart for anything, and so lay down to die, without even seeking for shelter.

“To make matters worse— better, I should say— at the very time of the outbreak the Congoora races were being held, and there were no less than 200,000 people on the race course, most of whom were smitten with sunstroke, frightened to death, or died of heat and exhaustion before they could reach any place of shelter. The horses themselves took fright, and raced away at the top of their speed, some of them never stopping till they fell dead.

“However, I cannot relate every incident of the day, and if I could, my account would be a mere repetition of ghastly scenes. The cave, as I remarked, was a large one, and was known to everybody in the district. Hence, as soon as night permitted people to travel, they came thronging in by thousands. Trains now ran from distant places to the station nearest the cavern, and all through that night droves of people continued to arrive. I soon saw that this large influx of people must lead to calamity—that the remedy would be quite as bad as the disease; though I felt far too hopeless to care much what happened; for I was morally certain that the end of the world was close at hand.

“I soon saw, however, that many others in the cavern were by no means given up yet to despair; and that they were prepared to make a struggle for existence, even at the cost of their fellows. Those people looked with jealous eye upon every new arrival; about midnight they organized themselves into a band to prevent by force any more from entering the cave. The party thus banded together were about 300 in number, and as the mouth of the cave was not more than nine or ten yards wide, they were amply sufficient to prevent all further ingress.

“Promptly they placed a guard against the cave’s mouth, armed with sticks and such other weapons as they could find at hand. The people in the cave were fully at one with the members of the band, whom they regarded as their defenders, and already we began to feel a hatred towards the poor wretches who were hurrying to the cave for shelter. Pity was gone: Nature had ceased to care for us, and we, imitating her example, left off caring for one another. Outside our new dwelling all was quickly in a state of confusion: people kept arriving by hundreds, and hurried up to the cave’s mouth confident of admittance. The sentries told them there was no room, and refused to let any pass. Mothers with infants, and persons of all descriptions came forward to seek shelter from the heat of the coming day; but after the sentries had been posted every applicant was ruthlessly turned away. We, inside, heard their bitter lamentations, and had we been open to the appeals of humanity we must have pitied them; but our hearts were steeled by calamity and terror, and being destitute of all hope ourselves, we were beyond the power of feeling for the woes of others.

“As the number outside continued to increase it was feared by those within that an attempt might be made to storm the cave. This anticipation turned out to be correct, for early in the morning several hundred men, no better armed than our own garrison, made a desperate onslaught upon our sentries. A fight ensued, which lasted, with little intermission till sunrise, when those outside, having gained no advantage, though they fought with the courage of despair, once more turned to prayers and entreaties, and with bitter lamentations besought us to let them in. Had we been so minded, it would only have prolonged their sufferings, besides augmenting ours. As it was, they were finally refused, and when the sun rose with fiercer heat even than on the previous day, most of the poor wretches drooped and withered away as fast as the herbs and grass around them.

“But we inside might have envied their fate; their sufferings were sharp and soon over, ours were more lingering. The first night we had plenty of food, though many thousands of us were there; but most of it was devoured by the time the first breakfast was over. As for water, there was plenty of that to get within the cave, there being a good cool spring, and a large standing pool.

“But the prospect was the most appalling that could be conceived. Hunger assailed us before noon of the second day; a few people had brought a good stock of provisions, that is, for themselves; but it was nothing for so many. And it soon became evident that those who had food to spare would not be allowed to keep it for their own wants. Before the end of the second day there were several fights over a few pounds of bread, and by nightfall not a crust was left among the thousands of people in the cavern.”

“But why,” said I, “did they not go out at night and gather up provisions wherever they might be found?”

“That,” replied the astronomer, “is a simple question, and what you suggest seems to you easy enough to have been done; but every one in the cave was more or less panic struck, and preferred to face the known dangers of the cave rather than venture upon the unknown ones without. Indeed, one small party did go out to forage during the second night; but they never returned, and we never found out what became of them. Others were afraid to go out, lest they should be refused admittance again; for no one any longer had faith in his fellows, nor would the most solemn promise have been received by anyone.

“There was nothing for us, therefore, but to abide our fate. To go out was certain death: to stay in was to face famine and disease. The heat was frightful even in the cave, the thermometer standing at 150° Fah., and still rising; we were constantly in a Turkish bath, and our thirst became agonizing in the extreme, though we tried to allay it by copious draughts of water. Our supply of the precious liquid was plentiful enough for the first few days; but before a week had passed the bubbling spring had fallen very low, and the water in the pool had all evaporated. The heat also was constantly increasing both within and without: the sun burned the fiercer on every successive day, and animals, and plants, and trees were literally roasted to cinders; and I verily believe the earth would have become red-hot had the solar blaze continued to scorch her surface as it did during the first few days.

“From this fate we were preserved—not that anything better followed—by an unexpected but perfectly natural phenomenon. Though I was well-versed in meteorology, I had in my bewilderment entirely over-looked the probability of what followed. Of course the sun could not continue shining as it did without causing excessive evaporation. Under his horrid blaze the ocean reeked, the rivers were soon dry, and all ice disappeared from the mountains and poles of the earth. The air soon became loaded with water-vapour, and the heat as a consequence was tempered a little, and in a few days the earth was covered with a hot steam, which rose even to the height of the loftiest mountains. Through this dense vapour the sun when visible at all appeared like a great red disc, but frequently it was not seen for several consecutive days. But though an ocean of water had been carried into the atmosphere, there was not a drop of rain for the whole six months that the sun was burning, for the cold was never sufficient to condense the moisture, and it was a rarity even to see dew.”

Here the astronomer paused a moment as if to refresh his memory, and I saw with anxiety the wild look and frenzied eye return, which made me fear that I had heard as much of his story as he would be able to relate. To my relief, however, he soon calmed himself and began again.

“You will not suppose,” he resumed, “that all this change was effected quietly—that so much water could be raised into the air without great meteorological agitation. Nature was fairly mad, and all her demeanour was most uproarious. Instead of quiet evaporation, the atmosphere was the scene of the most gigantic storms. At times every species of tempest raged at once: thunder and lightening bellowed and flashed incessantly for days together, and the former reverberated through our cave with the most astounding din. Hurricanes swept along at such a speed that even large rocks were overturned by their power; and, of course, all the trees and houses in their path were swept away. At sea the destruction must have been frightful, though no one survived to tell of it, and we in the cave were too unconcerned for ourselves to have any care for the woes of others. As I remarked, the storms were almost incessant, and altogether unparallelled in violence. At times they made large rents in the vapour that shrouded the earth and exposed again hundreds of miles of her surface to the undimmed fierceness of the burning sun.

“All the while, too, from the very first day, the earth was incessantly bombarded by projectiles from the sun, which was manifestly in a state of explosion as well as of combustion. Sometimes the fragments fell for hours together over a given area of the earth, and lay piled in heaps, resembling ancient cairns, but much larger. Many sunk deep into the ground, and those that fell on hard rocks were completely pulverized. Many of the meteorites were tremendously large: one of more than 100 feet diameter fell a few miles from our den, and the concussion shook the ground like an earthquake. Another of prodigious dimensions fell upon the mountain in which our cave was situated, and we thought the whole was about to collapse and bury us in its ruins. As it was, only a large part of our roof fell in, killing and burying some 200 persons in its fall.

“But all this was nothing. When the sun had been burning about a month we felt such a shock as cannot be described in human language, one effect of which was to throw us in the cave either violently down upon the floor or against the western wall. What was the cause of the tremendous jerk we could not then divine. We heard the most appalling noises, and felt no doubt that the mountains all around us were falling into ruin. Indeed, from the mouth of our hiding place I saw one mountain suddenly snap asunder at the moment of the concussion, and its upper half toppled over into the valley that lay at its western foot. But the most remarkable result of the shock was the shortening of the day; for I found to my amazement that the earth now performed her diurnal revolution in twenty hours instead of twenty-four, as formerly.

“The explanation will scarcely be credited, though I know, from personal inspection, that it is true. At the time alluded to, as I ascertained subsequently, an enormous projectile from the sun, scores of miles in diameter, struck the earth on the Western coast of Africa. The shock was the most terrific that could be conceived; the ribs of the earth were shattered by it. The projectile buried itself many miles deep in the earth’s crust; the waters of the Atlantic around the spot rushed into the chasm after the sun-shot, and there they were actually made to boil for days by the heat generated by the concussion. In addition to minor effects, the shot gave the earth such a wrench as made her spin faster upon her axis, thus shortening the day, as I before stated.

“While all those things were going on outside, we in the cavern were suffering every kind of torture and misery. The heat alone made the place a very hell. Then came famine and fevers and all other descriptions of sickness. In six weeks we were reduced to 100 in number, and many of those were by that time delirious. The survivors had nothing to live upon but the bodies of the dead, and this was our only food for about six months. Do you wonder that I am mad?” he said, turning to me.

“No!” I replied; “I wonder how you contrived to keep alive so long, in such horrible circumstances.”

He took no notice of my answer, but suddenly went on again.

“The cave was soon a charnel house, and the stench was worse than that of an opened sepulchre: ventilation was impossible, and the atmosphere became loaded with every foulness and with odours of the most deleterious nature. Those who had any heart left committed suicide, and the rest lay down to die with the most perfect indifference. But the things I have named did not comprise the sum of our miseries. Fights and quarrels were of daily occurrence, and what was more horrible still, we had not lost our old relish for delicacies, and the dry, shrunken corpses of those who died of disease and famine failed to satisfy our dainty taste, and we exercised our ingenuity to catch game more worthy of digestion. I don’t know who first suggested it, or who was the first to satisfy his cravings in the way I am about to describe; but of this I am certain, there was no one of us all that had the slightest scruple about it.

“Whenever we were wanting fresh meat, as we termed it, several of us would band together, and having singled out the very best man or woman of the lot, watched our opportunity to give the death blow. This, at times, was no easy matter. No one had faith in his fellows; and it was often found that several parties unknown to each other were conspiring at the same time, and it frequently turned out that a conspirator in one party had been marked as a victim by another party. This always gave us trouble—we were chary of shedding too much blood, and often when plots and counter plots were being executed simultaneously more persons were killed than could at once be eaten; and thus our most delicious feasts were frequently marred by the bitter reflection that we had foolishly wasted good and necessary food in struggling for a dainty.

“Things went on in the way I have roughly described till not more than three of us were left. At that time we had been six months in the cavern, and the sun was burning fiercely still. At intervals throughout our long period of confinement we had ventured out in twos and threes whenever the fog was dense enough to screen us from the rays of the sun. But this was attended with danger, and on several occasions parties who had ventured out when the atmosphere was unsteady had been scorched to death by the sudden rending of the vapour-screen, and the consequent downrush of solar heat. When we were out, walking was hardly possible, on account of the rarity of the atmosphere; we panted for breath, and after tottering a few steps, were compelled to sit and rest. The blood also burst through the skin, especially at the lips; and the load we seemed to sustain was intolerable. We felt this in a great measure in the cave, but outside it was many times worse.

“One day near the end of the conflagration, we three latest survivors crept into the city of Congoora, where to our surprise we found a few persons still living, but in a state of madness. Had they possessed the power we should have fared badly at their hands, for they regarded us three as the authors of their calamities. But they were as powerless to attack us as we were to defend ourselves, and the worst we got from them were malicious looks and gestures, which we returned to the best of our ability.

“One fellow especially attracted our attention. He sat under a bank, surrounded by bags of money, which he had with incredible patience and labour collected from the forsaken houses. There he sat, with cart loads of gold and silver within his reach. He was too intensely occupied in counting and arranging his money to bestow upon us even a glance. For some time we watched him as we sat and rested, and were just about to move away again, when down came a large meteorite, knocking the miser and his treasure far into the ground. We laughed at the incident, and then made our way back towards the cave, feeling that as easy and sudden an exit from life and misery would be most welcome to us. But no meteorite pitied our wretchedness, and we had the misfortune to enter the gloomy cavern once more.

* * * * * * * *

“By the way,” he exclaimed, energetically, as if a new thought had struck him, “instead of sitting here we might walk as far as the cave. I have not been there since the sun left off burning. Would you like to go and see it?”

“By all means,” replied I. And the old man at once arose and led the way. While I had sat listening to my informant all personal interests I had forgotten; but as soon as we rose I remembered that I was soon to go back to England, never for a moment perceiving the incongruity between my intended voyage and the fact that I was listening to a record of the end of the world. However, I had no power to refuse to accompany my guide, and so I followed wherever he might lead. We turned down a large desolate valley, and I became conscious that the cold was infinitely sharper than any I had ever before felt. The ice covered all the ground several yards in depth. On our way we passed some very extensive ruins, which my guide told me were those of the city of Congoora.

“Up there,” he said, pointing to a building on a low hill, “is my old observatory. You see how the sunshots have battered it.”

He paused for a few seconds, and looked as if he would like to take me up to see the sacred ruins; but suddenly started off again towards the cave. After wending on in silence for a mile or two, he before, and I following, my guide turned abruptly round, and pointing to an enormous mountain of debris, said,

“There it is! There is the mountain that snapt asunder and fell into the valley when the earth got that extra twist I mentioned.”

On we went again, and never slackened our pace, till we had reached the mouth of the Hunter’s Cavern. From the portal I found a most intolerable odour proceeding, but the old man motioned me to follow him, and I, perforce, entered the cave. My guide, by some means that I could not detect, lit a torch as soon as he was fairly in, and with this in his hand he showed me around the den. At every step I was stumbling over skeletons, or detached portions of them; but among all the obstacles that crowded our path my guide passed light as a fairy, and unerring as a stream that winds through a meandering valley. When we reached a particular corner, he halted, and pointing to a number of bones that lay pretty near together, he said,

“There are the ruins of my wife and children, four daughters and two sons. All eaten up during the famine.”

This was all he said, and then he took me to another part of the cave.

“There!” said he, stopping in front of a large heap of rubbish, “you now see the place where our roof fell in and buried so many people, as I told you. Plenty of good food buried there,” he continued, “but we were too weak to dig it out. Now, I will take you to see a spot that I have not mentioned.”5Original does not include quotation marks before “but.”

At this he started off at a rapid pace, which I found difficult to equal. I seem to see him now, hurrying through that infernal place: the torch held higher than his head, and his long hair streaming behind. The surrounding gloom, made more horrid by the glare of the torch, seemed the proper setting for such a picture. My eyes were riveted upon him, and several times I fell over skeletons that lay in my path. Ghosts and spectres too—so I fully believed—met me at every turn, and hobgoblins flitted around my head, muttering dreadful and mysterious whispers. Horrible sensations possessed me, and the sweat stood out in large cold drops upon my skin. “Was this old man the Devil,” thought I, “leading me away to his place of horrors?” And my heart stood still with terror. But man, or angel, or devil, I had no power to stop. How far we travelled through that region of horrors I cannot tell, but suddenly my guide stopped, and turning half round to me, said,

“Look!”

In the lurid light of the torch I saw that the old astronomer was standing upon a small projecting ledge of rock, which overhung a dark chasm whose depth I could not divine. Wishing to know something of it, I took up a stone and threw it down the pit, counting one, two, three, &c., to mark the time of its descent. It went down, down, but I heard nothing—no sound floated back to tell me that the stone had reached the bottom. I tried several others with the same results, my guide watching me with evident amusement. At length he laughed, and said:

“Nobody knows how deep that chasm is—except,” he added after a brief pause, “they who have gone down there, perhaps.”

“Do you mean to tell me,” said I, “that any people have gone down into that frightful chasm?”

“Many! Many!” he replied. “The crag I am standing on is the Crag of Deliverance. Ah! I forgot to tell you that.”

“Why is it called by that name?” I inquired.

“Why, don’t you see, this is where they used to come and leap into the chasm, when they were tired of life—the people in the cavern did, I mean, after the sun caught fire. There were many among us that had an insane antipathy to human flesh, and rather than eat others or be eaten themselves, they slunk away here and sprang into the darkness. Hundreds did that; I was nearly doing it myself several times, but some strange power held me back. However, I shall go that way at last.”

Before I could reply he was rushing away from the precipice back through the cavern towards the entrance. I followed after as best I could, never losing sight of the torch, though its bearer was far ahead. At length we reached the cavern’s mouth, and emerged into the open air, when I saw hanging in the sky a round disc, about as bright as tarnished brass, with large dark patches on it.

“That,” said the astronomer, “is the old burnt-out sun. I must stay to see its very last flicker, and then I shall go too. It is nearly done, I see, and I must make haste to tell you the rest of my tale.

“You remember that I told you of three of us going to the town when the sun had been burning for about six months. Well, that night we lay down and slept till morning, and when I awoke I found my comrades dead. I need not tell you how I did for breakfast; but early in the morning I went to the mouth of the cave and found that there had been a little rain, and the sky was more misty than I had seen it before since we first entered the cave. For several days I had thought that the heat had declined somewhat in its intensity, and now when I saw the wet ground, I knew that the solar fire was well nigh burnt out. I felt neither hope nor fear at the prospect now before me—things could not be worse, and I could not see any chance of improvement. Every day the temperature diminished, and at the end of a fortnight the water fell from the clouds in cataracts, and never ceased for nearly a month. Hurricanes also raged with horrible violence, and all through the wet and stormy season I was compelled to keep my den, where I felt terribly cold, though the heat was still tropical.6The original omits the space between “the clouds.” To keep myself warm I kept a fire constantly burning, and put on all the clothes I could find around me. When the rain ceased I went out, and saw the sun so far diminished in splendour that I could look him in the face without any inconvenience to my eyes. In a few days after, the mountains were again covered with snow, and even around the cave the frost was several inches thick. Little snow fell on the plains, as most of the moisture had come down as rain and hail. It soon became so cold that I thought the very air itself would freeze: every particle of moisture was frozen out of it, and the brilliancy of the firmament was so magnificent, as seen through an absolutely pure atmosphere, that I began, for the first time, to wish myself back with my telescopes. Had they not been battered to pieces by the meteorites I could not have resisted the desire to go up to my observatory and turn them upon the heavens. But—it was too late.

“In six weeks after the first rainfall the ocean was frozen over, and I felt a strong impulse to travel. I crossed the ocean and rounded the whole world, travelling over the ice. I don’t know why I did it, nor how I lived all the time. There was nothing to be seen but ice, ice everywhere. Over this, when it was smooth, I slid like a skater, going at a tremendous speed. No living thing was to be seen anywhere—death and silence possessed the whole earth.

“At times during my journey the sun would suddenly blaze out afresh, and for a few hours scorch me unbearably. But every fresh outburst only left him the darker when it was over. A voice, so it seemed, often whispered to me that I must remain alive as long as the sun continued to shine. Many a time I thought I had seen his last flicker, and joyfully hoped that my exit was at hand; but all my hopes had hitherto ended in disappointment. But to-day the voice whispers that my task is done. When I found you sitting under the tree I was just returned from my ramble round the world. I have told my story; and now you know how the world was destroyed.”

He had scarcely ceased speaking when the sun once more flashed up with a brilliancy quite overpowering. The old man’s face brightened as he watched it. The signs of madness were gone for the time, and he stood before me in all the majesty of intellectual life.

“That is his dying struggle,” said he, alluding to the sun. “Worthy of himself, he will expire in a flood of glory, rivalling even his old splendour, when worlds rejoiced at his rising and manifold life throbbed in ecstasy as he ran his daily race.”7For “ecstasy” the original reads “ecstacy.”

While the astronomer was thus speaking the sun suddenly exploded like a bomb-shell; and we distinctly saw the flickering fragments flying in all directions across the heavens. These were soon extinguished in utter darkness, and the sun was no more. All the light we now had left was given by the stars.

Suddenly the astronomer caught hold of my hand, and led me away in silence to the cave, and on through the dense darkness towards the chasm. I felt alarmed now for my safety, and tried to disengage my hand. This was impossible, I found, and no choice was left me but to follow. After a long journey, he halted, and lit his torch, in the light of which I found that he was standing again upon the crag of Deliverance.

“Ah!” said he, “I told you I should go this way at last, and now I am going! My deliverance is now at hand, and you must go with me!”

I would have remonstrated, or defended myself, but I was speechless, and so chilled with horror that I could move neither hand nor tongue. Besides, I was completely fascinated by his look. Suddenly he flung his torch down the abyss, and before the darkness had fairly closed round us, I was fast locked in the astronomer’s embrace. The next moment I felt him take the fatal leap, with me in his arms, and we were falling, falling, down, down the terrible chasm! A wild yell broke from me, as soon as my tongue was loose, and with that I wakened up, covered with cold sweat, and trembling terribly from head to foot.8The original ends with a comma rather than a period. As soon as I was sufficiently sane to comprehend my situation, I found that the ground around me was being rocked by a considerable earthquake; and it was this phenomenon, probably, that gave rise to my dream.

Who shall say the dream may not some day be fulfilled? Who knows but that the Solar System may wind up its tragi-comedy in the way described?

Word Count: 9393

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Jesse Myphos. “A Burnt-Out Sun and a Frozen World: A Wild Dream.” The Young Emancipator, vol. 1, no. 6, 1878, pp. 121-43. Edited by Anelise Leishman. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 6 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/a-burnt-out-sun-and-a-frozen-world/.

Editors

Anelise Leishman

Savannah Porter

Ana Hirschi

Cosenza Hendrickson

Eden Buchert

Posted

20 March 2020

Last modified

6 March 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | In the original, the paragraph begins with a quotation mark. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Original text reads “then” instead of “than.” |

| ↑3 | The original had no punctuation at the end of this sentence. |

| ↑4 | Original text does not include a space between “by meteorites.” |

| ↑5 | Original does not include quotation marks before “but.” |

| ↑6 | The original omits the space between “the clouds.” |

| ↑7 | For “ecstasy” the original reads “ecstacy.” |

| ↑8 | The original ends with a comma rather than a period. |