A Dialogue on Art

by John Orchard

The Germ: Thoughts Toward Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art, vol. 1, issue 4 (1850)

Pages 146-167

Introductory Note: Presented as a dialogue between four allegorical figures, this closet drama is a meditation on aesthetics. The characters’ names are Kalon, Kosmon, Sophon, and Christian, signifying beauty, order, sophistry, and Christianity, respectively, and each espouses the construct of art that its name suggests.

Not much is known about the author of “A Dialogue on Art,” John Ontand, known as John Orchard in the Pre-Raphaelite journal The Germ: Thoughts Towards Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art. He was sick throughout his life and died before his dialogue was printed. In the preface to a later edition of the periodical, the editor William Michael Rossetti describes him as “unknown” in their literary circle; while writing the preface to The Germ, he goes so far as to say that “no memory remains of him at the present day.”1William Michael Rossetti, “Introduction,” The Germ: Thoughts Toward Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art, London: Eliot Stock, 1901: 25. Orchard, however, was profoundly influenced by William’s brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti; he even sent a sonnet based on the Rossetti painting “The Girlhood of Mary Virgin” to the artist.2William Rossetti, 25. Although unconnected with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he showcases questions about art and ethics that were at the heart of Pre-Raphaelite inquiry.

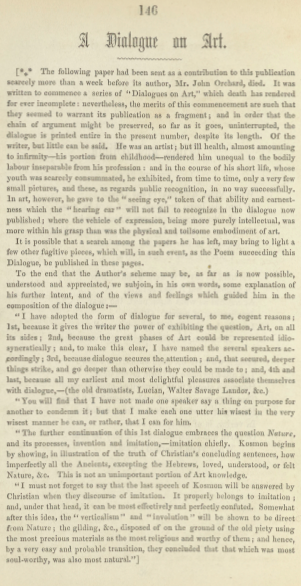

At its inception, Orchard planned for the work to be written in four parts, each building on the last and facilitating more discussion about the characters’ opinions on art, as Dante Gabriele Rossetti claims in his preface to the dialogue; however, because of his untimely death in 1850, he was unable to complete the three corresponding sections.3Introductory Note, “A Dialogue on Art,” The Germ, Vol. 1 No. 4, 1850, 146. The PDF posted at the end of this transcription includes the introductory note. Nonetheless, the first and only part of the unfinished dialogues is able to stand alone as a well-crafted discussion of the importance and characteristics of art.

In a later introduction, William Rossetti suggests that the story’s author favored Christian’s puritanical and religious views, though he noted that the concepts of art that each character proposes are supported to some extent. Therefore, each differing perspective is illustrated as rational, if not correct.4William Rossetti, 26.

Dialogue I., in the House of Kalon.

Kalon. Welcome, my friends:—this day above all others; to-day is the first day of spring. May it be the herald of a bountiful year,—not alone in harvests of seeds. Great impulses are moving through man; swift as the steam-shot shuttle, weaving some mighty pattern, goes the new birth of mind. As yet, hidden from eyes is the design: whether it be poetry, or painting, or music, or architecture, or whether it be a divine harmony of all, no manner of mind can tell; but that it is mighty, all manners of minds, moved to involuntary utterance, affirm. The intellect has at last again got to work upon thought: too long fascinated by matter and prisoned to motive geometry, genius—wisdom seem once more to have become human, to have put on man, and to speak with divine simplicity. Kosmon, Sophon, again welcome! your journey is well-timed; Christian, my young friend, of whom I have often written to you, this morning tells me by letter that to-day he will pay me his long-promised visit. You, I know, must rejoice to meet him: this interchange of knowledge cannot fail to improve us, both by knocking down and building up: what is true we shall hold in common; what is false not less in common detest. The debateable ground, if at last equally debateable as it was at first, is yet ploughed; and some after-comer may sow it with seed, and reap therefrom a plentiful harvest.

Sophon. Kalon, you speak wisely. Truth hath many sides like a diamond with innumerable facets, each one alike brilliant and piercing. Your information respecting your friend Christian has not a little interested me, and made me desirous of knowing him.

Kosmon. And I, no less than Sophon, am delighted to hear that we shall both see and taste your friend.

Sophon. Kalon, by what you just now said, you would seem to think a dearth of original thought in the world, at any time, was an evil: perhaps it is not so; nay, perhaps, it is a good! Is not an interregnum of genius necessary somewhere? A great genius, sun-like, compels lesser suns to gravitate with and to him; and this is subversive of originality. Age is as visible in thought as it is in man. Death is indispensably requisite for a new life. Genius is like a tree, sheltering and affording support to numberless creepers and climbers, which latter die and live many times before their protecting tree does; flourishing even whilst that decays, and thus, lending to it a greenness not its own; but no new life can come out of that expiring tree; it must die: and it is not until it is dead, and fallen, and rotted into compost, that another tree can grow there; and many years will elapse before the new birth can increase and occupy the room the previous one occupied, and flourish anew with a greenness all its own. This on one side. On another; genius is essentially imitative, or rather, as I just now said, gravitative; it gravitates towards that point peculiarly important at the moment of its existence; as air, more rarified in some places than in others, causes the winds to rush toward them as toward a centre: so that if poetry, painting, or music slumbers, oratory may ravish the world, or chemistry, or steam-power may seduce and rule, or the sciences sit enthroned. Thus, nature ever compensates one art with another; her balance alone is the always just one; for, like her course of the seasons, she grows, ripens, and lies fallow, only that stronger, larger, and better food may be reared.

Kalon. By your speaking of chemistry, and the mechanical arts and sciences, as periodically ruling the world along with poetry, painting, and music,—am I to understand that you deem them powers intellectually equal, and to require of their respective professors as mighty, original, and human a genius for their successful practice?

Kosmon. Human genius! why not? Are they not equally human?—nay, are they not—especially steam-power, chemistry and the electric telegraph—more—eminently more—useful to man, more radically civilizers, than music, poetry, painting, sculpture, or architecture?

Kalon. Stay, Kosmon! whither do you hurry? Between chemistry and the mechanical arts and sciences, and between poetry, painting, and music, there exists the whole totality of genius—of genius as distinguished from talent and industry. To be useful alone is not to be great: plus only is plus, and the sum is minus something and plus in nothing if the most unimaginable particle only be absent. The fine arts, poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and architecture, as thought, or idea, Athene-like, are complete, finished, revelations of wisdom at once. Not so the mechanical arts and sciences: they are arts of growth; they are shaped and formed gradually, (and that, more by a blind sort of guessing than by intuition,) and take many men’s lives to win even to one true principle. On all sides they are the exact opposites of each other; for, in the former, the principles from the first are mature, and only the manipulation immature; in the latter, it is the principles that are almost always immature, and the manipulation as constantly mature. The fine arts are always grounded upon truth; the mechanical arts and sciences almost always upon hypothesis; the first are unconfined, infinite, immaterial, impossible of reduction into formulas, or of conversion into machines; the last are limited, finite, material, can be uttered through formulas, worked by arithmetic, tabulated and seen in machines.

Sophon. Kosmon, you see that Kalon, true to his nature, prefers the beautiful and good, to the good without the beautiful; and you, who love nature, and regard all that she, and what man from her, can produce, with equal delight,—true to your’s,—cannot perceive wherefore he limits genius to the fine arts. Let me show you why Kalon’s ideas are truer than yours. You say that chemistry, steam-power, and the electric telegraph, are more radically civilizers than poetry, painting, or music: but bethink you: what emotions beyond the common and selfish ones of wonder and fear do the mechanical arts or sciences excite, or communicate? what pity, or love, or other holy and unselfish desires and aspirations, do they elicit? Inert of themselves in all teachable things, they are the agents only whereby teachable things,—the charities, sympathies and love,—may be more swiftly and more certainly conveyed and diffused: and beyond diffusing media the mechanical arts or sciences cannot get; for they are merely simple facts; nothing more: they cannot induct; for they, in or of themselves, have no inductive powers, and their office is confined to that of carrying and spreading abroad the powers which do induct; which powers make a full, complete, and visible existence only in the fine arts. In Fact and Thought we have the whole question of superiority decided. Fact is merely physical record: Thought is the application of that record to something human. Without application, the fact is only fact, and nothing more; the application, thought, then, certainly must be superior to the record, fact. Also in thought man gets the clearest glimpse he will ever have of soul, and sees the incorporeal make the nearest approach to the corporeal that it is possible for it to do here upon earth. And hence, these noble acts of wisdom are—far—far above the mechanical arts and sciences, and are properly called fine arts, because their high and peculiar office is to refine.

Kosmon. But, certainly thought is as much exercised in deducting from physical facts the sciences and mechanical arts as ever it is in poetry, painting, or music. The act of inventing print, or of applying steam, is quite as soul-like as the inventing of a picture, poem, or statue.

Kalon. Quite. The chemist, poet, engineer, or painter, alike, think. But the things upon which they exercise their several faculties are very widely unlike each other; the chemist or engineer cogitates only the physical; the poet or painter joins to the physical the human, and investigates soul—scans the world in man added to the world without him—takes in universal creation, its sights, sounds, aspects, and ideas. Sophon says that the fine arts are thoughts; but I think I know a more comprehensive word; for they are something more than thoughts; they are things also; that word is Nature—Nature fully—thorough nature—the world of creation. All that is in man, his mysteries of soul, his thoughts and emotions—deep, wise, holy, loving, touching, and fearful,—or in the world, beautiful, vast, ponderous, gloomy, and awful, moved with rhythmic harmonious utterance—that is Poetry. All that is of man—his triumphs, glory, power, and passions; or of the world—its sunshine and clouds, its plains, hills, or valleys, its wind-swept mountains and snowy Alps, river and ocean—silent, lonely, severe, and sublime—mocked with living colours, hue and tone,—that is Painting. Man—heroic man, his acts, emotions, loves,—aspirative, tender, deep, and calm,—intensified, purified, colourless,—exhibited peculiarly and directly through his own form; that is sculpture. All the voices of nature—of man—his bursts of rage, pity, and fear—his cries of joy—his sighs of love; of the winds and the waters—tumultuous, hurrying, surging, tremulous, or gently falling—married to melodious numbers; that is music. And, the music of proportions—of nature and man, and the harmony and opposition of light and shadow, set forth in the ponderous; that is Architecture.

Christian. [as he enters] Forbear, Kalon! These I know for your dear friends, Kosmon and Sophon. The moment of discoursing with them has at last arrived: May I profit by it! Kalon, fearful of checking your current of thought, I stood without, and heard that which you said: and, though I agree with you in all your definitions of poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and architecture; yet certainly all things in or of man, or the world, are not, however equally beautiful, equally worthy of being used by the artist. Fine art absolutely rejects all impurities of form; not less absolutely does it reject all impurities of passion and expression. Everything throughout a poem, picture, or statue, or in music, may be sensuously beautiful; but nothing must be sensually so. Sins are only paid for in virtues; thus, every sin found is a virtue lost—lost—not only to the artist, but a cause of loss to others—to all who look upon what he does. He should deem his art a sacred treasure, intrusted to him for the common good; and over it he should build, of the most precious materials, in the simplest, chastest, and truest proportions, a temple fit for universal worship: instead of which, it is too often the case that he raises above it an edifice of clay; which, as mortal as his life, falls, burying both it and himself under a heap of dirt. To preserve him from this corruption of his art, let him erect for his guidance a standard awfully high above himself. Let him think of Christ; and what he would not show to as pure a nature as His, let him never be seduced to work on, or expose to the world.

Kosmon. Oh, Kalon, whither do we go! Greek art is condemned, and Satire hath got its death-stroke. The beautiful is not the beautiful unless it is fettered to the moral; and Virtue rejects the physical perfections, lest she should fall in love with herself, and sin and cause sin.

Christian. Nay, Kosmon. Nothing pure,—nothing that is innocent, chaste, unsensual,—whether Greek or satirical, is condemned: but everything—every picture, poem, statue, or piece of music—which elicits the sensual, viceful, and unholy desires of our nature—is, and that utterly. The beautiful was created the true, morally as well as physically; vice is a deformment of virtue,—not of form, to which it is a parasitical addition—an accretion which can and must be excised before the beautiful can show itself as it was originally made, morally as well as formally perfect. How we all wish the sensual, indecent, and brutal, away from Hogarth, so that we might show him to the purest virgin without fear or blushing.

Sophon. And as well from Shakspere.5A common variant of Shakespeare. Rotten members, though small in themselves, are yet large enough to taint the whole body. And those impurities, like rank growths of vine, may be lopped away without injuring any vital principle. In perfect art the utmost purity of intention, design, and execution, alone is wisdom. Every tree—every flower, in defiance of adverse contingencies, grows with perfect will to be perfect: and, shall man, who hath what they have not, a soul wherewith he may defy all ill, do less?

Kosmon. But how may this purity be attained? I see every where close round the pricks; not a single step may be taken in advance without wounding something vital. Corruption strews thick both earth and ocean; it is only the heavens that are pure, and man cannot live upon manna alone.

Christian. Kosmon, you would seem to mistake what Sophon and I mean. Neither he nor I wish nature to be used less, or otherwise than as it appears; on the contrary, we wish it used more—more directly. Nature itself is comparatively pure; all that we desire is the removal of the factitious matter that the vice of fashion, evil hearts, and infamous desires, graft upon it. It is not simple innocent nature that we would exile, but the devilish and libidinous corruptions that sully nature.

Kalon. But, if your ideas were strictly carried out, there would be but little of worth left in the world for the artist to use; for, if I understand you rightly, you object to his making use of any passion, whether heroic, patriotic, or loving, that is not rigidly virtuous.

Christian. I do. Without he has a didactic aim; like as Hogarth had. A picture, poem, or statue, unless it speaks some purpose, is mere paint, paper, or stone. A work of art must have a purpose, or it is not a work of fine art: thus, then, if it be a work of fine art, it has a purpose; and, having purpose, it has either a good or an evil one: there is no alternative. An artist’s works are his children, his immortal heirs, to his evil as well as to his good; as he hath trained them, so will they teach. Let him ask himself why does a parent so tenderly rear his children. Is it not because he knows that evil is evil, whether it take the shape of angels or devils? And is not the parent’s example worthy of the artist’s imitation? What advantage has a man over a child? Is there any preservative peculiar to manhood that it alone may see and touch sin, and yet be not defiled? Verily, there is none! All mere battles, assassinations, immolations, horrible deaths, and terrible situations used by the artist solely to excite,—every passion degrading to man’s perfect nature,—should certainly be rejected, and that unhesitatingly.

Sophon.—Suffer me to extend the just conclusions of Christian. Art—true art—fine art—cannot be either coarse or low. Innocent-like, no taint will cling to it, and a smock frock is as pure as “virginal-chaste robes.” And,—sensualism, indecency, and brutality, excepted—sin is not sin, if not in the act; and, in satire, with the same exceptions, even sin in the act is tolerated when used to point forcibly a moral crime, or to warn society of a crying shame which it can remedy.

Kalon. But, my dear Sophon,—and you, Christian,—you do not condemn the oak because of its apples; and, like them, the sin in the poem, picture, or statue, may be a wormy accretion grafted from without. The spectator often makes sin where the artist intended none. For instance, in the nude,—where perhaps, the poet, painter, or sculptor, imagines he has embodied only the purest and chastest ideas and forms, the sensualist sees—what he wills to see; and, serpent-like, previous to devouring his prey, he covers it with his saliva.

Christian. The Circean poison, whether drunk from the clearest crystal or the coarsest clay, alike intoxicates and makes beasts of men. Be assured that every nude figure or nudity introduced in a poem, picture, or piece of sculpture, merely on physical grounds, and only for effect, is vicious. And, where it is boldly introduced and forms the central idea, it ought never to have a sense of its condition: it is not nudity that is sinful, but the figure’s knowledge of its nudity, (too surely communicated by it to the spectator,) that makes it so. Eve and Adam before their fall were not more utterly shameless than the artist ought to make his inventions. The Turk believes that, at the judgment-day, every artist will be compelled to furnish, from his own soul, soul for every one of his creations. This thought is a noble one, and should thoroughly awake poet, painter, and sculptor, to the awful responsibilities they labour under. With regard to the sensualist,—who is omnivorous, and swine-like, assimilates indifferently pure and impure, degrading everything he hears or sees,—little can be said beyond this; that for him, if the artist be without sin, he is not answerable. But in this responsibility he has two rigid yet just judges, God and himself;—let him answer there before that tribunal. God will acquit or condemn him only as he can acquit or condemn himself.

Kalon. But, under any circumstance, beautiful nude flesh beautifully painted must kindle sensuality; and, described as beautifully in poetry, it will do the like, almost, if not quite, as readily. Sculpture is the only form of art in which it can be used thoroughly pure, chaste, unsullied, and unsullying. I feel, Christian, that you mean this. And see what you do!—What a vast domain of art you set a Solomon’s seal upon! how numberless are the poems, pictures, and statues—the most beautiful productions of their authors—you put in limbo! To me, I confess, it appears the very top of prudery to condemn these lovely creations, merely because they quicken some men’s pulses.

Kosmon. And, to me, it appears hypercriticism to object to pictures, poems, and statues, calling them not works of art—or fine art—because they have no higher purpose than eye or ear-delight. If this law be held to be good, very few pictures called of the English school—of the English school, did I say?—very few pictures at all, of any school, are safe from condemnation: almost all the Dutch must suffer judgment, and a very large proportion of modern sculpture, poetry, and music, will not pass. Even “Christabel” and the “Eve of St. Agnes” could not stand the ordeal.6Romantic-era poems by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Keats.

Christian. Oh, Kalon, you hardly need an answer! What! shall the artist spend weeks and months, nay, sometimes years, in thought and study, contriving and perfecting some beautiful invention,—in order only that men’s pulses may be quickened? What!—can he, jesuit-like, dwell in the house of soul, only to discover where to sap her foundations?—Satan-like, does he turn his angel of light into a fiend of darkness, and use his God-delegated might against its giver, making Astartes and Molochs to draw other thousands of innocent lives into the embrace of sin? And as for you, Kosmon, I regard purpose as I regard soul; one is not more the light of the thought than the other is the light of the body; and both, soul and purpose, are necessary for a complete intellect; and intellect, of the intellectual—of which the fine arts are the capital members—is not more to be expected than demanded. I believe that most of the pictures you mean are mere natural history paintings from the animal side of man. The Dutchmen may, certainly, go Letheward; but for their colour, and subtleties of execution, they would not be tolerated by any man of taste.7“Letheward” was a term John Keats used to express the entrance in to lethargic-oblivion, or that which is created when one drinks from the River Lethe in Hades.

Sophon. Christian here, I think, is too stringent. Though walls be necessary round our flower gardens to keep out swine and other vile cattle,—yet I can see no reason why, with excluding beasts, we should also exclude light and air. Purpose is purpose or not, according to the individual capacity to assimilate it. Different plants require different soils, and they will rather die than grow on unfriendly ones; it is the same with animals; they endure existence only through their natural food; and this variety of soils, plants, and vegetables, is the world less man. But man, as well as the other created forms, is subject to the same law: he takes only that aliment he can digest. It is sufficient with some men that their sensoria be delighted with pleasurable and animated grouping, colour, light, and shade: this feeling or desire of their’s is, in itself, thoroughly innocent: it is true, it is not a great burden for them to carry; no, but it is the lightness of the burden that is the merit; for thereby, their step is quickened and not clogged, their intellect is exhilarated and not oppressed. Thus, then, a purpose is secured, from a picture or poem or statue, which may not have in it the smallest particle of what Christian and I think necessary for it to possess; he reckons a poem, picture, or statue, to be a work of fine art by the quality and quantity of thought it contains, by the mental leverage it possesses wherewith to move his mind, by the honey which he may hive, and by the heavenly manna he may gather therefrom.

Kosmon. Christian wants art like Magdalen Hospitals, where the windows are so contrived that all of earth is excluded, and only heaven is seen. Wisdom is not only shown in the soul, but also in the body: the bones, nerves, and muscles, are quite as wonderful in idea as is the incorporeal essence which rules them. And the animal part of man wants as much caring for as the spiritual: God made both, and is equally praised through each. And men’s souls are as much touchable and teachable through their animal feelings as ever they are through their mental aspirations; this both Orpheus and Amphion knew when they, with their music, made towns to rise in savage woods by savage hands. And hence, in that light, nothing is without a purpose; and I maintain,—if they give but the least glimpse of happiness to a single human being,—that even the Dutch masters are useful, I believe that the thought-wrapped philosopher, who, in his close-pent study, designs some valuable blessing for his lower and more animal brethren, only pursues the craving of his nature; and that his happiness is no higher than their’s in their several occupations and delights. Sight and sense are fully as powerful for happiness as thought and ratiocination. Nature grows flowers wherever she can; she causes sweet waters to ripple over stony beds, and living wells to spring up in deserts, so that grass and herbs may grow and afford nourishment to some of God’s creatures. Even the granite and the lava must put forth blossoms.

Kalon. Oh Christian, children cannot digest strong meats! Neither can a blind man be made to see by placing him opposite the sun. The sound of the violin is as innocent as that of the organ. And, though there be a wide difference in the sacredness of the occupations, yet dance, song, and the other amusements common to society, are quite as necessary to a healthy condition of the mind and body, as is to the soul the pursuit and daily practice of religion. The healthy condition of the mind and body is, after all, the happy life; and whether that life be most mental or most animal it matters little, even before God, so long as its delights, amusements, and occupations, be thoroughly innocent and chaste.

Christian. So long as the pursuits, pastimes, and pleasures of mankind be innocent and chaste,—with you all, heartily, I believe it matters little how or in what form they be enjoyed. Pure water is certainly equally pure, whether it trickle from the hill-side or flow through crystal conduits; and equally refreshing whether drunk from the iron bowl or the golden goblet;—only the crystal and gold will better please some natures than the hill-side and the iron. I know also that a star may give more light than the moon,—but that is up in its own heavens and not here on earth. I know that it is not light and shade which make a complete globe, but, as well, the local and neutral tints. Thus, my friends, you perceive that I am neither for building a wall, nor for contriving windows so as to exclude light, air, and earth. As much as any of you, I am for every man’s sitting under his own vine, and for his training, pruning, and eating its fruit how he pleases. Let the artist paint, write, or carve, what and how he wills, teach the world through sense or through thought,—I will not dissent; I have no patent to entitle me to do so; nay, I will be thoroughly satisfied with whatsoever he does, so long as it is pure, unsensual, and earnestly true. But, as the mental is the peculiar feature that places man apart from and above animals,—so ought all that he does to be apart from and above their nature; especially in the fine arts, which are the intellectual perfection of the intellectual. And nothing short of this intellectual perfection,—however much they may be pictures, poems, statues, or music,—can rank such works to be works of Fine Art. They may have merit,—nay, be useful, and hence, in some sort, have a purpose: but they are as much works of Fine Art as Babel was the Temple of Solomon.

Sophon. And man can be made to understand these truths—can be drawn to crave for and love the fine arts: it is only to take him in hand as we would take some animal—tenderly using it—entreating it, as it were, to do its best—to put forth all its powers with all its capable force and beauty. Nor is it so very difficult a task to raise, in the low, conceptions of things high: the mass of men have a fine appreciation of God and his goodness: and as active, charitable, and sympathetic a nurture in the beautiful and true as they have given to them in religion, would as surely and swiftly raise in them an equally high appreciation of the fine arts. But, if the artist would essay such a labour, he must show them what fine art is: and, in order to do this effectually, as an architect clears away from some sacred edifice which he restores the shambles and shops, which, like filthy toads cowering on a precious monument, have squatted themselves round its noble proportions; so must he remove from his art-edifice the deformities which hide—the corruptions which shame it.

Christian. How truly Sophon speaks a retrospective look will show. The disfigurements which both he and I deplore are strictly what he compared them to; they are shambles and shops grafted on a sacred edifice. Still, indigenous art is sacred and devoted to religious purposes: this keeps it pure for a time; but, like a stream travelling and gathering other streams as it goes through wide stretches of country to the sea, it receives greater and more numerous impurities the farther it gets from its source, until, at last, what was, in its rise, a gentle rilling through snows and over whitest stones, roars into the ocean a muddy and contentious river. Men soon long to touch and taste all that they see; savage-like, him whom to-day they deem a god and worship, they on the morrow get an appetite for and kill, to eat and barter. And thus art is degraded, made a thing of carnal desire—a commodity of the exchange. Yes, Sophon, to be instructive, to become a teaching instrument, the art-edifice must be cleansed from its abominations; and, with them, must the artist sweep out the improvements and ruthless restorations that hang on it like formless botches on peopled tapestry. The multitude must be brought to stand face to face with the pious and earnest builders, to enjoy the severely simple, beautiful, aspiring, and solemn temple, in all its first purity, the same as they bequeathed it to them as their posterity.

Kalon. The peasant, upon acquaintance, quickly prefers wheaten bread to the black and sour mass that formerly served him: and when true jewels are placed before him, counterfeit ones in his eyes soon lose their lustre, and become things which he scorns. The multitude are teachable—teachable as a child; but, like a child, they are self-willed and obstinate, and will learn in their own way, or not at all. And, if the artist wishes to raise them unto a fit audience, he must consult their very waywardness, or his work will be a Penelope’s web of done and undone: he must be to them not only cords of support staying their every weakness against sin and temptation, but also, tendrils of delight winding around them. But I cannot understand why regeneration can flow to them through sacred art alone. All pure art is sacred art. And the artist having soul as well as nature—the lodestar as well as the lodestone—to steer his path by—and seeing that he must circle earth—it matters little from what quarter he first points his course; all that is necessary is that he go as direct as possible, his knowledge keeping him from quicksands and sunken rocks.

Christian. Yes, Kalon;—and, to compare things humble—though conceived in the same spirit of love—with things mighty, the artist, if he desires to inform the people thoroughly, must imitate Christ, and, like him, stoop down to earth and become flesh of their flesh; and his work should be wrought out with all his soul and strength in the same world-broad charity, and truth, and virtue, and be, for himself as well as for them, a justification for his teaching. But all art, simply because it is pure and perfect, cannot, for those grounds alone, be called sacred: Christian, it may, and that justly; for only since Christ taught have morals been considered a religion. Christian and sacred art bear that relation to each other that the circle bears to its generating point; the first is only volume, the last is power: and though the first—as the world includes God—includes with it the last, still, the last is the greatest, for it makes that which includes it: thus all pure art is Christian, but not all is sacred. Christian art comprises the earth and its humanities, and, by implication, God and Christ also; and sacred art is the emanating idea—the central causating power—the jasper throne, whereon sits Christ, surrounded by the prophets, apostles, and saints, administering judgment, wisdom, and holiness.8Christ’s “jasper throne” is mentioned in Revelation 4:2-3 of the King James Bible. In this sense, then, the art you would call sacred is not sacred, but Christian: and, as all perfect art is Christian, regeneration necessarily can only flow thence; and thus it is, as you say, that, from whatever quarter the artist steers his course, he steers aright.

Kosmon. And, Christian, is a return to this sacred or Christian art by you deemed possible? I question it. How can you get the art of one age to reflect that of another, when the image to be reflected is without the angle of reflection? The sun cannot be seen of us when it is night! and that class of art has got its golden age too remote—its night too long set—for it to hope ever to grasp rule again, or again to see its day break upon it. You have likened art to a river rising pure, and rolling a turbid volume into the ocean. I have a comparison equally just. The career of one artist contains in itself the whole of art-history; its every phase is presented by him in the course of his life. Savage art is beheld in his childish scratchings and barbarous glimmerings; Indian, Egyptian, and Assyrian art in his boyish rigidity and crude fixedness of idea and purpose; Mediæval, or pre-Raffaelle art is seen in his youthful timid darings, his unripe fancies oscillating between earth and heaven; there where we expect truth, we see conceit; there where we want little, much is given—now a blank eyed riddle,—dark with excess of self,—now a giant thought—vast but repulsive,—and now angel visitors startling us with wisdom and touches of heavenly beauty. Every where is seen exactness; but it is the exactness of hesitation, and not of knowledge—the line of doubt, and not of power: all the promises for ripeness are there; but, as yet, all are immature. And mature art is presented when all these rude scaffoldings are thrown down—when the man steps out of the chrysalis a complete idea—both Psyche and Eros—free-thoughted, free-tongued, and free-handed;—a being whose soul moves through the heavens and the earth—now choiring it with angels—and now enthroning it, bay-crowned, among the men-kings;—whose hand passes over all earth, spreading forth its beauties unerring as the seasons—stretches through cloudland, revealing its delectable glories, or, eagle-like, soars right up against the sun;—or seaward goes seizing the cresting foam as it leaps—the ships and their crews as they wallow in the watery valleys, or climb their steeps, or hang over their flying ridges:—daring and doing all whatsoever it shall dare to do, with boundless fruitfulness of idea, and power, and line; that is mature art—art of the time of Phidias, of Raffaelle, and of Shakspere. And, Christian, in preferring the art of the period previous to Raffaelle to the art of his time, you set up the worse for the better, elevate youth above manhood, and tell us that the half-formed and unripe berry is wholesomer than the perfect and ripened fruit.

Christian. Kosmon, your thoughts seduce you; or rather, your nature prefers the full and rich to the exact and simple: you do not go deep enough—do not penetrate beneath the image’s gilt overlay, and see that it covers only worm-devoured wood. Your very comparison tells against you. What you call ripeness, others, with as much truth, may call over-ripeness, nay, even rottenness; when all the juices are drunk with their lusciousness, sick with over-sweetness. And the art which you call youthful and immature—may be, most likely is, mature and wholesome in the same degree that it is tasteful, a perfect round of beautiful, pure, and good. You call youth immature; but in what does it come short of manhood? Has it not all that man can have,—free, happy, noble, and spiritual thoughts? And are not those thoughts newer, purer, and more unselfish in the youth than in the man? What eye has the man, that the youth’s is not as comprehensive, keen, rapid, and penetrating? or what hand, that the youth’s is not as swift, forceful, cunning, and true? And what does the youth gain in becoming man? Is it freshness, or deepness, or power, or wisdom? nay rather—is it not languor—the languor of satiety—of indifferentism? And thus soul-rusted and earth-charmed, what mate is he for his former youth? Drunken with the world-lees, what can he do but pourtray nature drunken as well, and consumed with the same fever or stupor that consumes himself, making up with gilding and filagree what he lacks in truth and sincerity? and what comparison shall exist here and between what his youth might or could have done, with a soul innocent and untroubled as heaven’s deep calm of blue, gazing on earth with seraph eyes—looking, but not longing—or, in the spirit rapt away before the emerald-like rainbow-crowned throne, witnessing “things that shall be hereafter,” and drawing them down almost as stainless as he beheld them? What an array of deep, earnest, and noble thinkers, like angels armed with a brightness that withers, stand between Giotto and Raffaelle; to mention only Orcagna, Ghiberti, Masaccio, Lippi, Fra Beato Angelico, and Francia. Parallel them with post-Raffaelle artists? If you think you can, you have dared a labour of which the fruit shall be to you as Dead Sea apples, golden and sweet to the eye, but, in the mouth, ashes and bitterness. And the Phidian era was a youthful one—the highest and purest period of Hellenic art: after that time they added no more gods or heroes, but took for models instead—the Alcibiadeses and Phyrnes, and made Bacchuses and Aphrodites; not as Phidias would have—clothed with the greatness of thought, or girded with valour, or veiled with modesty; but dissolved with the voluptuousness of the bath, naked, wanton, and shameless.

Sophon. You hear, Kosmon, that Christian prefers ripe youth to ripe manhood: and he is right. Early summer is nobler than early autumn; the head is wiser than the hand. You take the hand to mean too much: you should not judge by quantity, or luxuriance, or dexterity, but by quality, chastity, and fidelity. And colour and tone are only a fair setting to thought and virtue. Perhaps it is the fate, or rather the duty, of mortals to make a sacrifice for all things, withheld as well as given. Hand sometimes succumbs to head, and head in its turn succumbs to hand; the first is the lot of youth, the last of manhood. The question is—which of the two we can best afford to do without. Narrowed down to this, I think but very few men would be found who would not sacrifice in the loss of hand in preference to its gain at the loss of head.

Kosmon. But, Christian, in advocating a return to this pre-Raffaelle art, are you not—you yourself—urging the committal of “ruthless restorations” and “improvements,” new and vile as any that you have denounced? You tell the artist, that he should restore the sacred edifice to its first purity—the same as it was bequeathed by its pious and earnest builders. But can he do this and be himself original? For myself, I would above all things urge him to study how to reproduce, and not how to represent—to imitate no past perfection, but to create for himself another, as beautiful, wise, and true. I would say to him, “build not on old ground, profaned, polluted, trod into slough by filthy animals; but break new ground—virgin ground—ground that thought has never imagined or eye seen, and dig into our hearts a foundation, deep and broad as our humanity. Let it not be a temple formed of hands only, but built up of us—us of the present—body of our body, soul of our soul.”

Christian. When men wish to raise a piece of stone, or to move it along, they seek for a fulcrum to use their lever from; and, this obtained, they can place the stone wheresoever they please. And world-perfections come into existence too slowly for men to reject all the teaching and experience of their predecessors: the labour of learning is trifling compared to the labour of finding out; the first implies only days, the last, hundreds of years. The discovery of the new world without the compass would have been sheer chance; but with it, it became an absolute certainty. So, and in such manner, the modern artist seeks to use early mediæval art, as a fulcrum to raise through, but only as a fulcrum; for he himself holds the lever, whereby he shall both guide and fix the stones of his art temple; as experience, which shall be to him a rudder directing the motion of his ship, but in subordination to his control; and as a compass, which shall regulate his journey, but which, so far from taking away his liberty, shall even add to it, because through it his course is set so fast in the ways of truth as to allow him, undividedly, to give up his whole soul to the purpose of his voyage, and to steer a wider and freer path over the trackless, but to him, with his rudder and compass, no longer the trackless or waste ocean; for, God and his endeavours prospering him, that shall yield up unto his hands discoveries as man-worthy as any hitherto beheld by men, or conceived by poets.

Kalon. But, Christian, another artist with equal justness might use Hellenic art as a means toward making happy discoveries; formatively, there is nothing in it that is not both beautiful and perfect; and beautiful things, rainbow-like, are once and for ever beautiful; and the contemplation and study of its dignified, graceful, and truthful embodiments—which, by common consent, it only is allowed to possess in an eminent and universal degree—is full as likely to awaken in the mind of its student as high revelations of wisdom, and cause him to bear to earth as many perfections for man, as ever the study of pre-Raffaelle art can reveal or give, through its votary.

Christian. But beautiful things, to be beautiful in the highest degree, like the rainbow, must have a spiritual as well as a physical voice. Lovely as it is, it is not the arch of colours that glows in the heavens of our hearts; what does, is the inner and invisible sense for which it was set up of old by God, and of which its many-hued form is only the outward and visible sign. Thus, beautiful things alone, of themselves, are not sufficient for this task; to be sufficient they must be as vital with soul as they are with shape. To be formatively perfect is not enough; they must also be spiritually perfect, and this not locally but universally. The art of the Greeks was a local art; and hence, now, it has no spiritual. Their gods speak to us no longer as gods, or teach us divinely: they have become mere images of stone—profane embodiments. False to our spiritual, Hellenic art wants every thing that Christian art is full of. Sacred and universal, this clasps us, as Abraham’s bosom did Lazarus, within its infinite embraces, causing every fibre of our being to quicken under its heavenly truths. Ithuriel’s golden spear was not more antagonistic to Satan’s loathly transformation—than is Christian opposed to pagan art. The wide, the awful gulf, separating one from the other, will be felt instantly in its true force by first thinking Zeus, and then thinking Christ. How pale, shadowy, and shapeless the vision of lust, revenge, and impotence, that rises at the thought of Zeus; but at the thought of Christ, how overwhelming the inrush of sublime and touching realities; what height and depth of love and power; what humility, and beauty, and immaculate purity are made ours at the mention of his name; the Saviour, the Intercessor, the Judge, the Resurrection and the Life. These—these are the divinely awful truths taught by our faith; and which should also be taught by our art. Hellenic art, like the fig tree that only bore leaves, withered at Christ’s coming; and thus no “happy discoveries” can flow thence, or “revelations of wisdom,” or other perfections be borne to earth for man.

Sophon. Christian thinks and says, that if the spiritual be not in a thing, it cannot be put upon it; and hence, if a work of art be not a god, it must be a man, or a mere image of one; and that the faith of the Pagan is the foolishness of the Christian. Nor does he utter unreason; for, notwithstanding their perfect forms, their gods are not gods to us, but only perfect forms: Apollo, Theseus, the Ilissus, Aphrodite, Artemis, Psyche, and Eros, are only shapeful manhood, womanhood, virginhood, and youth, and move us only by the exact amount of humanity they possess in common with ourselves. Homer, and Æschylus, and Sophocles, and Phidias, live not by the sacred in them, but by the human: and, but for this common bond, Hellenic art would have been submerged in the same Lethe that has drowned the Indian, Egyptian, and Assyrian Theogonies and arts. And, if we except form, what other thing does Hellenic art offer to the modern artist, that is not thoroughly opposed to his faith, wants, and practice? And thought—thought in accordance with all the lines of his knowledge, temperament, and habits—thought through which he makes and shapes for men, and is understood by them—it is as destitute of, as inorganic matter of soul and reason. But Christian art, because of the faith upon which it is built, suffers under no such drawbacks, for that faith is as personal and vigorous now as ever it was at its origin—every motion and principle of our being moves to it like a singing harmony;—it is the breath which brings out of us, Æolian-harp-like, our most penetrating and heavenly music—the river of the water of life, which searches all our dry parts and nourishes them, causing them to spring up and bear abundantly the happy seed which shall enrich and make fat the earth to the uttermost parts thereof.

Kalon. With you both I believe, that faith is necessary to a man, and that without faith sight even is feeble: but I also believe that a man is as much a part of the religious, moral, and social system in which he lives, as is a plant of the soil, situation, and climate in which it exists: and that external applications have just as much power to change the belief of the man, as they have to alter the structure of the plant. A faith once in a man, it is there always; and, though unfelt even by himself, works actively: and Hellenic art, so far from being an impediment to the Christian belief, is the exact reverse; for, it is the privilege of that belief, through its sublime alchymy, to be able to transmute all it touches into itself: and the perfect forms of Hellenic art, so touched, move our souls only the more energetically upwards, because of their transcendent beauty; for through them alone can we see how wonderfully and divinely God wrought—how majestic, powerful, and vigorous he made man—how lovely, soft, and winning, he made woman: and in beholding these things, we are thankful to him that we are permitted to see them—not as Pagans, but altogether as Christians. Whether Christian or Pagan, the highest beauty is still the highest beauty; and the highest beauty alone, to the total exclusion of gods and their myths, compels our admiration.

Kosmon. Another thing we ought to remember, when judging Hellenic Art, is, but for its existence, all other kinds—pre-Raffaelle as well—could not have had being. The Greeks were, by far, more inclined to worship nature as contained in themselves, than the gods—if the gods are not reflexes of themselves, which is most likely. And, thus impelled, they broke through the monstrous symbolism of Egypt, and made them gods after their own hearts; that is, fashioned them out of themselves. And herein, I think we may discern something of providence; for, suppose their natures had not been so powerfully antagonistic to the traditions and conventions of their religion, what other people in the world could or would have done their work? Cast about a brief while in your memories, and endeavor to find whether there has ever existed a people who in their nature, nationality, and religion, have been so eminently fitted to perform such a task as the Hellenic? You will then feel that we have reason to be thankful that they were allowed to do what else had never been done; and, which not done, all posterity would have suffered to the last throe of time. And, if they have not made a thorough perfection—a spiritual as well as a physical one—forget not that, at least, they have made this physical representation a finished one. They took it from the Egyptians, rude, clumsy, and seated; its head stony—pinned to its chest; its hands tied to its side, and its legs joined; they shaped it, beautiful, majestic, and erect; elevated its head; breathed into it animal fire; gave movement and action to its arms and hands; opened its legs and made it walk—made it human at all points—the radical impersonation of physical and sensuous beauty. And, if the god has receded into the past and become a “pale, shadowy, and shapeless vision of lust, revenge, and impotence,” the human lives on graceful, vigorous, and deathless, as at first, and excites in us admiration as unbounded as ever followed it of old in Greece or Italy.

Christian. Yes, Kosmon, yes! they are flourished all over with the rhetoric of the body; but nowhere is to be seen in them that diviner poetry, the oratory of the soul! Truly they are a splendid casket enclosing nothing—at least nothing now of importance to us; for what they once contained, the world, when stirred with nobler matter, disregarded, and left to perish. But, Kosmon, we cannot discuss probabilities. Our question is—not whether the Greeks only could have made such masterpieces of nature and art; but whether their works are of that kind the most fitted to carry forward to a more ultimate perfection that idea which is peculiarly our’s. All art, more or less, is a species of symbolism; and the Hellenic, notwithstanding its more universal method of typification, was fully as symbolic as the Egyptian; and hence its language is not only dead, but forgotten, and is now past recovery: and, if it were not, what purpose would be served by its republication? For, for whom does the artist work? The inevitable answer is, “For his nation!” His statue, or picture, poem, or music, must be made up and out of them; they are at once his exemplars, his audience, and his worshippers; and he is their mirror in which they behold themselves as they are: he breathes them vitally as an atmosphere, and they breathe him. Zeus, Athene, Heracles, Prometheus, Agamemnon, Orestes, the House of Œdipus, Clytemnestra, Iphigenia, and Antigone, spoke something to the Hellenic nations; woke their piety, pity, or horror,—thrilled, soothed, or delighted them; but they have no charm for our ears; for us, they are literally disembodied ghosts, and voiceless as shapeless. But not so are Christ, and the holy Apostles and saints, and the Blessed Virgin; and not so is Hamlet, or Richard the Third, or Macbeth, or Shylock, or the House of Lear, Ophelia, Desdemona, Grisildis, or Una, or Genevieve. No: they all speak and move real and palpable before our eyes, and are felt deep down in the heart’s core of every thinking soul among us:—they all grapple to us with holds that only life will loose. Of all this I feel assured, because, a brief while since, we agreed together that man could only be raised through an incarnation of himself. Tacitly, we would also seem to have limited the uses of Hellenic art to the serving as models of proportion, or as a gradus for form: and, though I cannot deny them any merit they may have in this respect, still, I would wish to deal cautiously with them: the artist,—most especially the young one, and who is and would be most subject to them and open to their influence,—should never have his soul asleep when his hand is awake; but, like voice and instrument, one should always accompany the other harmoniously.

Kosmon. But surely you will deal no less cautiously with early mediæval art. Archaisms are not more tolerable in pictures than they are in statues, poems, or music; and the archaisms of this kind of art are so numerous as to be at first sight the most striking feature belonging to it. Most remarkable among these unnatural peculiarities are gilded backgrounds, gilded hair, gilded ornaments and borders to draperies and dresses, the latter’s excessive verticalism of lines and tedious involution of folds, and the childlike passivity of countenance and expression: all of which are very prominent, and operate as serious drawbacks to their merits; which—as I have freely admitted—are in truth not a few, nor mean.

Christian. The artist is only a man, and living with other men in a state of being called society; and,—though perhaps in a lesser degree—he is as subject to its influences—its fashions and customs—as they are. But in this respect his failings may be likened to the dross which the purest metal in its molten state continually throws up to its surface, but which is mere excrement, and so little essential that it can be skimmed away: and, as the dross to the metal, just so little essential are the archaisms you speak of to the early art, and just so easily can they be cast aside. But bethink you, Kosmon. Is Hellenic art without archaisms? And that feature of it held to be its crowning perfection—its head—is not that a very marked one? And, is it not so completely opposed to the artist’s experience in the forms of nature that—except in subjects from Greek history and mythology—he dares not use it—at least without modifying it so as to destroy its Hellenism?

Sophon. Then Hellenic Art is like a musical bell with a flaw in it; before it can be serviceable it must be broken up and recast. If its sum of beauty—its line of lines, the facial angle, must be destroyed—as it undoubtedly must—before it can be used for the general purposes of art, then its claims over early mediæval art, in respect of form, are small indeed. But is it not altogether a great archaism?

Kalon. Oh, Sophon! weighty as are the reasons urged against Hellenic art by Christian and yourself, they are not weighty enough to outbalance its beauty, at least to me: at present they may have set its sun in gloom; yet I know that that obscuration, like a dark foreground to a bright distance, will make its rising again only the more surpassingly glorious. I admire its exquisite creations, because they are beautiful, and noble, and perfect, and they elevate me because I think them so; and their silent capabilities, like the stardust of heaven before the intellectual insight, resolve themselves into new worlds of thoughts and things so ever as I contemplate their perfections: like a prolonged music, full of sweet yet melancholy cadences, they have sunk into my heart—my brain—my soul—never, never to cease while life shall hold with me. But, for all that, my hands are not full; and, whithersoever the happy seed shall require me, I am not for withholding plough or spade, planting or watering; and that which I am called in the spirit to do—will I do manfully and with my whole strength.

Sophon. Kalon, the conclusion of your speech is better than the commencement. It is better to sacrifice myrrh and frankincense than virtue and wisdom, thoughts than deeds. Would that all men were as ready as yourself to dispark their little selfish enclosures, and burn out all their hedges of prickly briers and brambles—turning the evil into the good—the seed-catching into the seed-nourishing. Of the too consumptions let us prefer the active, benevolent, and purifying one of fire, to the passive, self-eating, and corrupting one of rust: one half minute’s clear shining may touch some watching and waiting soul, and through him kindle whole ages of light.

Christian. Men do not stumble over what they know; and the day fades so imperceptibly into night that were it not for experience, darkness would surprise us long before we believed the day done: and, in relation to art, its revolutions are still more imperceptible in their gradations; and, in fulfilling themselves, they spread over such an extent of time, that in their knowledge the experience of one artist is next to nothing; and its twilight is so lengthy, that those who never saw other, believe its gloom to be day; nor are their successors more aware that the deepening darkness is the contrary, until night drops big like a great clap of thunder, and awakes them staringly to a pitiable sense of their condition. But, if we cannot have this experience through ourselves, we can through others; and that will show us that Pagan art has once—nay twice—already brought over Christian art a “darkness which might be felt;” from a little handful cloud out of the studio of Squarcione, it gathered density and volume through his scholar Mantegna—made itself a nucleus in the Academy of the Medici, and thence it issued in such a flood of “heathenesse” that Italy finally became covered with one vast deep and thick night of Pagandom.9“Darkness which might be felt” comes from Exodus 10:21. But in every deep there is a lower deep; and, through the same gods-worship, a night intenser still fell upon art when the pantomime of David made its appearance. With these two fearful lessons before his eyes, the modern artist can have no other than a settled conviction that Pagan art, Devil-like, glozes but to seduce—tempts but to betray; and hence, he chooses to avoid that which he believes to be bad, and to follow that which he holds to be good, and blots out from his eye and memory all art between the present and its first taint of heathenism, and ascends to the art previous to Raffaelle; and he ascends thither, not so much for its forms as he does for its Thought and Nature—the root and trunk of the art-tree, of whose numerous branches form is only one—though the most important one: and he goes to pre-Raffaelle art for those two things, because the stream at that point is clearer and deeper, and less polluted with animal impurities, than at any other in its course. And, Kalon and Kosmon, had you remembered this, and at the same time recollected that the words “Nature” and “Thought” express very peculiar ideas to modern eyes and ears—ideas which are totally unknown to Hellenic Art—you would have instantly felt, that the artist cannot study from it things chiefest in importance to him—of which it is destitute, even as is a shore-driven boulder of life and verdure.

Word Count: 10113

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

John Orchard. “A Dialogue on Art.” The Germ: Thoughts Toward Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art, vol. 1, no. 4, 1850, pp. 146-67. Edited by Paige Thompson. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 1 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/a-dialogue-on-art/.

Editors

Paige Thompson

Rachel Housley

Lesli Mortensen

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

9 July 2020

Last modified

28 June 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | William Michael Rossetti, “Introduction,” The Germ: Thoughts Toward Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art, London: Eliot Stock, 1901: 25. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William Rossetti, 25. |

| ↑3 | Introductory Note, “A Dialogue on Art,” The Germ, Vol. 1 No. 4, 1850, 146. The PDF posted at the end of this transcription includes the introductory note. |

| ↑4 | William Rossetti, 26. |

| ↑5 | A common variant of Shakespeare. |

| ↑6 | Romantic-era poems by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Keats. |

| ↑7 | “Letheward” was a term John Keats used to express the entrance in to lethargic-oblivion, or that which is created when one drinks from the River Lethe in Hades. |

| ↑8 | Christ’s “jasper throne” is mentioned in Revelation 4:2-3 of the King James Bible. |

| ↑9 | “Darkness which might be felt” comes from Exodus 10:21. |