A Prize Marriage, Part 1

by Anonymous

The Young Englishwoman, vol. 1, July issue (1867)

Pages 362-367

Introductory Note: Targeted toward an audience of middle-class young women, The Young Englishwoman’s content often focused on love, courtship, and marriage. Countering the expectation that the magazine would teach young ladies propriety within a certain system of social rules, “A Prize Marriage” actually explores questions such as: Should we marry for money or for love? Which of these marriages is most successful? This story is an important portrayal of a dilemma faced by many of the magazine’s young readers, advocating for a balance between social convention and emotion.

Advisory: This story depicts ableism.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the first of two parts:

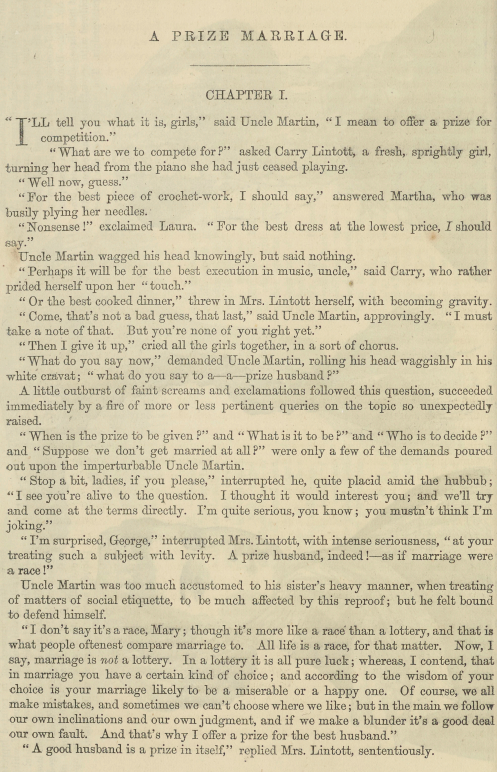

CHAPTER I.

“I’ll tell you what it is, girls,” said Uncle Martin, “I mean to offer a prize for competition.”

“What are we to compete for?” asked Carry Lintott, a fresh, sprightly girl, turning her head from the piano she had just ceased playing.

“Well now, guess.”

“For the best piece of crochet-work, I should say,” answered Martha, who was busily plying her needles.

“Nonsense!” exclaimed Laura. “For the best dress at the lowest price, I should say.”

Uncle Martin wagged his head knowingly, but said nothing.

“Perhaps it will be for the best execution in music, uncle,” said Carry, who rather prided herself upon her “touch.”

“Or the best cooked dinner,” threw in Mrs. Lintott herself, with becoming gravity.

“Come, that’s not a bad guess, that last,” said Uncle Martin, approvingly. “I must take a note of that. But you’re none of you right yet.”

“Then I give it up,” cried all the girls together, in a sort of chorus.

“What do you say now,” demanded Uncle Martin, rolling his head waggishly in his white cravat; “what do you say to a—a—prize husband?”

A little outburst of faint screams and exclamations followed this question, succeeded immediately by a fire of more or less pertinent queries on the topic so unexpectedly raised.

“When is the prize to be given?” and “What is it to be?” and “Who is to decide?” and “Suppose we don’t get married at all?” were only a few of the demands poured out upon the imperturbable Uncle Martin.

“Stop a bit, ladies, if you please,” interrupted he, quite placid amid the hubbub; “I see you’re alive to the question. I thought it would interest you; and we’ll try and come at the terms directly. I’m quite serious, you know; you mustn’t think I’m joking.”

“I’m surprised, George,” interrupted Mrs. Lintott, with intense seriousness, “at your treating such a subject with levity. A prize husband, indeed!—as if marriage were a race!”

Uncle Martin was too much accustomed to his sister’s heavy manner, when treating of matters of social etiquette, to be much affected by this reproof; but he felt bound to defend himself.

“I don’t say it’s a race, Mary; though it’s more like a race than a lottery, and that is what people oftenest compare marriage to. All life is a race, for that matter. Now, I say, marriage is not a lottery. In a lottery it is all pure luck; whereas, I contend, that in marriage you have a certain kind of choice; and according to the wisdom of your choice is your marriage likely to be a miserable or a happy one. Of course, we all make mistakes, and sometimes we can’t choose where we like; but in the main we follow our own inclinations and our own judgment, and if we make a blunder it’s a good deal our own fault. And that’s why I offer a prize for the best husband.”

“A good husband is a prize in itself,” replied Mrs. Lintott, sententiously.

“And a good wife, too, I should think, ma,” cried Laura; “and a much greater prize.”

“You are quite right, my dear,” said Mrs. Lintott, “and I think both a good wife and a good husband are far out of the range of lotteries or races either.”

“Very well, Mary,” smiled Uncle Martin, in his easy, composed way, “we won’t discuss that question, because I believe we are both pretty well of one mind, so far as that goes. But I stick to my proposal: I’ll give a hundred pounds to the girl who makes the best match—twelve months after marriage.”

“But who is to decide, uncle?” asked Carry, with a shade of anxiety on her face, as if it were already a question for decision.

“Not the wife, my dear,” answered Uncle Martin, with a sly twinkle in his eye, “or I might have to give three prizes instead of one. No,” settling his alarmingly red face in his dazzlingly white cravat, “I shall appoint a committee of spinsters to award the prize.”

“Oh, indeed!” cried Laura. “Then I’m sure I shouldn’t submit to their verdict. You had better appoint a committee of married ladies, Uncle.”

“Perhaps,” continued he, “ I may make it a mixed jury; and, if there’s any difference of opinion, I shall claim the right of giving the casting vote.”

“But suppose I choose to remain single, uncle?” asked Laura, a little loftily.

“Then, my dear, you don’t compete; and you are out of the race, or the lottery, or whatever else you may choose to call it.”

“But if we don’t get any husbands at all?” inquired Martha, dolorously, “what then, uncle?”

“Why then, perhaps, I’ll divide the money among you as a little bit of comfort. But never fear, girls,” added Uncle Martin, his face radiant with fun and kindliness. “You’ll all be married before the year’s out; and you’ll all make such good matches that you’ll want to give me—each of you—a hundred pounds for only suggesting the idea of a prize husband. See if you don’t.”

The Lintott family consisted of the mother and her three daughters. Mr. Samuel Lintott, the head of the family, a successful corn-factor, had lived just long enough to secure a very modest provision for his relict and his children, and had died at fifty-two of ossification of the heart. He had been a good husband and a kind father, and his children had reaped the benefit of his instruction and his example. He had not amassed sufficient property to enable his children to remain idle at home, or to leave them any more than a very small dowry; such a dowry, indeed, as removed them from the category of portionless girls, but by no means enough to draw suitors to their side who had an eye to pecuniary advantages. They were, on the whole, good and sensible girls; not without their little weaknesses and fits of temper, but still affectionate, prudent, and industrious. It must be added that not even their female friends disputed their claims to beauty. Laura was the eldest, the proudest, and, perhaps, the prettiest. By right of priority of birth, she claimed the privilege of remaining at home with her mother, while her two sisters, who did not dispute her claim, “went out” as governesses—Caroline in a private family, and Martha at a select school. They had never been taught to regard a position of honourable labour as degrading, and fulfilled its responsibilities fairly and uncomplainingly. Of the three sisters, Carry was certainly the most clever, especially at her music, and was, upon the whole, the greatest favourite among their acquaintances. Laura was thought to be sometimes haughty, and Martha a little dull, but Carry was always sprightly, good-tempered, and ready for all emergencies. Her prim, methodical friends were inclined to call her “forward,” and sometimes shook their heads sagely as to her future, but all admired her talents, and were pleased with her readiness and her amiability. It was only at some holiday season that the three sisters were at home together, and it was just such a season which enabled Uncle Martin, who was on a visit to his sister, Mrs. Lintott, to make his waggish, but really serious, intention known of giving a money prize of one hundred pounds to the one of his nieces who should make the best match.

Mr. Richard Martin, or Uncle Martin, as he was called by his nieces, was a bachelor, a member of the legal profession, and a man in easy circumstances. It was not suspected that he would leave much behind him, for he was a free-liver, and of expensive habits. He was always welcome, for he was gay, chatty, and well versed in the current events of the day. Of a ponderous build, his manner corresponded with his figure, and was rather droll than vivacious; but to the quiet family of the Lintotts his stories and jokes were always fresh and entertaining. Mrs. Lintott was of a grave and reflective turn of mind, and rather strict in her notion of the proprieties. She, therefore, did not at all fall in with her brother’s idea of a prize marriage, and openly stigmatized it as “unbecoming.”

“As if,” she exclaimed, indignantly, “girls were to think of nothing but how to get rich husbands!”

Whether the intention of Uncle Martin, openly proclaimed, had really any effect in stimulating the efforts of the three sisters in their matrimonial researches, it would not be easy, and certainly would not be fair, to say. Beyond the rather spiteful assertion with regard to Carry’s “forwardness,”—which forwardness, after all, was nothing more than the natural expression of a frank, cheerful temperament,—there was not a whisper to the detriment of the modesty and reserve of the young Misses Lintott; but whatever the cause, it is undoubted that soon after that announcement was made, there arose rumors of serious attentions, and even positive engagements, in reference to two at least of the trio, viz., Laura and Martha, which excited very lively attention on the part of the Lintott neighbourhood.

It was soon openly asserted that Miss Laura Lintott had made a great “catch,” an expression for which the writer will be by no means responsible, and of which he cannot sufficiently express his disapproval, as being neither elegant nor complimentary. Still that was the word—a great “catch.” Nothing less than the son of a banker, and a very handsome young man, indeed. Miss Martha’s conquest was said to be of a much humbler kind: only a school-usher, but who, being the son and heir of a schoolmaster, might be supposed to have in prospect the wielding of the academical ferula on his own account. Of Carry, in her distant home as governess, there came no tidings on Cupid’s wing. She wrote as usual, and had the same pleasant, contented story to tell of her scholarly duties, but nothing about promises, or overtures, or engagements, with the most distant view to matrimony. So people shook their heads, and expressed their wonder that Miss Caroline, who was such a sprightly, promising girl, was less fortunate than her sisters; although it was no wonder at all, they added, seeing that her witty frankness and “forwardness” was likely to frighten her lovers away.

“Don’t tell me!” cried Uncle Martin, rubbing his hands violently together, when he was told of these things. “Carry’s all right; she’ll pull through, I know. People like a pleasant face, and a lively manner, and it’s only the slow-coaches who can’t keep up with that sort of thing. I wonder who’ll win?”

CHAPTER II.

If ever there was a slow-coach on the road of life, it was Mr. Sampson, the school-usher, and Martha Lintott’s beau. To be sure, there was a pair of them, and in so far they got on very well together. Mr. Sampson was a tall, slim young man, with a stoop at his shoulders, who talked dictionary words in a solemn, pretentious way, and who yet was as dull and timid in his manner as if he had been himself a school-boy, perpetually under the master’s eye. Now, Martha herself was not remarkably lively, and with a companion of ordinary glibness of tongue, would have been quiet and reserved as to satisfy even prudery itself; but in the presence of Mr. Sampson, and moved, as it were, by the very weight of his silence, she became a miracle of conversational ability. How Mr. Sampson had ever communicated to the young lady the affection which glowed in his heart would be beyond comprehension, if one did not know that love had a silent language as well as a spoken one. Nevertheless, it was always observed that Martha, after any one of her arduous interviews, at which her mother or some female friend was always present, was overtaken by an uncontrollable desire to yawn.

Mr. Sampson was second master—he was simply second, because he was not first, for there was no third master—or chief usher at an “academy” in the immediate neighbourhood of the “seminary” at which Miss Martha Lintott was under-governess, and it was exceedingly natural that, as each led his or her little troop of scholars to church on Sunday, or for a stately promenade on week-days, they should see, should observe, and, as it happened in this case, should admire each other. Then, little complications would arise in the management of their several charges, now in the preservation of due order and behaviour in the little processions, now in the induction into the pews at church appropriated to their use. There would occasionally be trifling confusions to correct, or open rebellion to suppress, which would call forth the administrative abilities of each, and which brought them into immediate contact. The gravity of these situations was sometimes tremendous. Master Tommy would be led kicking to his offended superior, and delivered over in awful silence to retribution. Miss Cissy would be carried bodily in a weeping or highly refractory state to her outraged mistress, and left solemnly for punishment. And so the chief usher and the under-governess, in the ordinary discharge of their responsible duties, would naturally be thrown into each other’s company, and led to speak, and think, and love, as a necessary consequence.

It could hardly be said that similarity of disposition was the chord which chimed in unison in the breasts of Mr. Sampson and Miss Lintott. On the contrary, it was the firmness and decision of the under-governess which charmed the chief usher, while it was the mildness and equanimity of the chief usher which delighted the under-governess. So both were mutually attracted by their opposites. Perhaps the very restraints imposed upon them by their position secretly cherished and inflamed their inclinations for each other; for they were metaphorically and actually moving and acting in the sight of a hundred inquisitive and intelligent eyes—the inquisitive and intelligent eyes of their own pupils, who, moreover, were provided with sharp, ready tongues to tell the stories their eyes had suggested to them. Under these circumstances, Mr. Sampson’s diffidence might be explained while in the shadow of the academy, and the shadow of the academy was an abiding shadow that followed him whithersoever he went.

Mr. Lunge, the banker’s son, who had become captive to Laura Lintott’s charms, was a town young gentleman, with all the town’s smartness, and some, at least, of the town’s laxity of habit. He certainly was not a reserved young man, nor a young man of taciturn manners. He said a great deal, although it was a favourite expression of his that he was “a man of few words.” In one respect, at least, he was a man of few words, but then, as his friends remarked, he repeated these words so often that he might as well have had a good many. But he was a banker’s son, and knew how the great financial world of the City rose and fell, and could talk of “bulls” and “bears,” and the rate of exchange in London, and Paris, and Amsterdam, and the price of stocks and the ebbing and flowing of the value of shares in great companies. And so he was listened to, and allowed to talk on at his will, and the consequence was that, with a few clear facts here and there, he talked a great deal of nonsense.

Mr. Lunge was a middle-sized, fleshy young man, with a pink and white complexion, light hair, and pale gray eyes, which seemed rather too large for his eyelids. He dressed expensively, and what was called “well,” but it was a showy, flashy sort of excellence, conspicuous for light and bright colours, and strange contrasts. Then he made use of a great deal of slang—not precisely low, common slang—but a style of language which, while attempting to be eminently expressive, was especially shallow, and ungrammatical, and cloudy. And all this as evidence of smartness, and as a proof of his knowledge of life and the ways of the great city. It is difficult to say how Mr. Lunge, judged by this description, could be considered a fitting match for Laura Lintott, who was really a girl with much good sense, sincerely and morally religious, and handsome withal—which last is something. But the fact is, that there were so many other young men who were like Mr. Lunge that his defects and peculiarities appeared less than they were, simply because they were defects and peculiarities common and tolerated. Then Mr. Lunge was not vicious, if he was shallow, and he did not mock at the church, as many young men did, but was at least outwardly religious, if not sincerely devout. It is impossible to say how far the fact of his position and prospects may have influenced both mother and daughter in their encouragement of Mr. Lunge’s advances; but one might safely assume that in any other than a banker’s son, or a person of the like status, his weak sallies and slangy conversation would have been checked instead of being smiled at, and so virtually encouraged.

The debateable land of courtship had been gained by the two pairs of lovers—Laura Lintott and Mr. Lunge, Martha and Mr. Sampson. Nothing was defined, but everything was hoped for. Each had advanced too far lightly to recede, without having made any actual settlement of the momentous question which hung suspended between them. Then came a letter from Caroline to her mother. It startled the good lady almost out of her wits. Carry had been unusually silent for some time, but as there was no reason to suppose that this silence was the result of anything beyond pressure of occupation, or perhaps indolence—though that was not like Carry—it excited little notice, more especially as the anxious mother had been fully occupied with the affairs of Laura at home, and of Martha by constant letters and occasional visits at her seminary in the suburbs.

This letter of Carry’s was like a thunder-clap. Its contents were in themselves uncommon, and they were totally unexpected. Its language was more tender, more humble, more pleading than any Carry had ever written home before, affectionate as her letters usually were, and yet it was not wanting in a sort of decision and firmness which was characteristic of the writer. In effect, it asked her mother’s blessing on her intended marriage. That was the sum of it, and it gave but few details. Carry did not so much ask permission or sanction for the step she was about to take; that was implied in the blessing she sought upon her union. There was a tone in her letter of entreaty, of dread, lest her simple request might be denied—as if she feared to ask the more important question, regarding that as beyond discussion, and sought the acceptance of a position already defined by herself, in the knowledge of its existence by her mother. Yet nothing could be more humble. She was coming home, Carry wrote and then she would explain all; but she would not have dared to come home with so many things upon her lips and upon her heart untold, and had, therefore, written this letter that they might be prepared. And who was the favoured one? He was a German, named Karl Rubelstein, a musician, and a teacher of languages; “so clever, so good, so handsome!” wrote Carry, “I am sure you will like him. And although he’s blind——”

“Blind!” half shrieked Mrs. Lintott, letting the letter fall out of her hands, and sinking back into her chair. “Good heavens! What infatuation! What is the foolish girl thinking about?”

Yet so it was. This “clever, handsome, good” young German was blind, and this was the responsibility which the simple English girl, tenderly nurtured, carefully trained, and never yet pained by the stress of poverty, was about to take upon herself.

When Uncle Martin heard this news, the roseate colour of his face paled with surprise and vexation. Carry was his favourite, too.

“I can never consent to it,” sobbed Mrs. Lintott.

“She won’t win the prize, at any rate,” growled Uncle Martin.

“Suppose I refuse to sanction it?” appealed Mrs. Lintott.

“Then they’ll marry without your sanction,” answered Uncle, grimly, “and that will be the end of that. I can see that by her letter.”

“She must be mad.”

“Dear, dear, dear!” muttered Uncle Martin. “To think that my pretty little Carry should go and marry a blind fiddler!”

“He may not be a fiddler,” remonstrated Mrs. Lintott, shocked at the idea.

“Well, he’s blind, at any rate,” grumbled Uncle Martin. “Perhaps he plays the bassoon.”

Word Count: 3652

This story is continued in A Prize Marriage, Part 2.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

“A Prize Marriage, Part 1.” The Young Englishwoman, vol. 1, no. July, 1867, pp. 362-7. Edited by Brook Brundage. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 22 February 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/a-prize-marriage/.

Editors

Brook Brundage

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

16 January 2021

Last modified

22 February 2026