A Spectre’s Dilemma

The Idler, vol. 1, issue 2 (1892)

Pages 194-205

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: In 1892, Eden Phillpotts published “A Spectre’s Dilemma” in the Idler, a monthly gentlemen’s periodical known for its comedy and satire. Through the story of a “second-rate phantom,” Phillpotts humorously critiques typical ghost story tropes.

IT IS quite enough in this materialistic age to say that I am a ghost for people to turn up their noses at me; and when I add that I am a very second-rate phantom, a spirit with the most mean spectral privileges, it will be readily gathered that my position in ghostly circles is more or less a painful one.

To be plain, I am not an awe-inspiring apparition in any sense; I am not even passable; I never raised the hair or froze the blood; adults gaze unmoved at my most fearsome manifestations; children like me.

But I am a right ghost for all that. Time and space possess no significance for me, and hundreds of people have mistaken me for luminous paint after dark. Against these advantages, however, must be set the unhappy conditions of smallness and stoutness; for as in life I had been of diminutive and plump habit, so did I now remain. I am, in fact, a short, fat ghost—a combination of qualities that promised from the first to be fatal to anything tremendous or out of the common.

Thus, though I have haunted in all the best middle-class families, and once or twice taken a locum tenens among county people; though I have foretold deaths, indicated buried treasure, pointed out secret staircases, corpses and so forth; though I have gone through the regular mill, my spirit has yet failed of acquiring even a reasonable reputation among men.1Locum tenens: a person who temporarily fulfills the duties of another.

For the past fifty years I have dwelt in Herefordshire with some pleasant, self-made folks who suit me very well. Capon Hall is a roomy mansion, possessing architectural advantages from my point of view, and situated in a somewhat densely-haunted district. The original owners got themselves destroyed in the time of Charles I., and the property, after many fluctuations of fortune, was ultimately purchased by Mr. John Smithson, a Manchester man. Here he resided, developed into a good old Squire of the right sort, and grew popular. He was a widower, and had two children, Ethel, a girl of eighteen, who lived with him, and William, a son of two or three and twenty, who entered the army and went to India. This youth married, became the father of a daughter, and sent the infant home to Capon Hall. Now, love may often appear where there is no respect, and when an element of real human affection entered into my ghostly life, I found it a comfortable and pleasing thing.

This baby Smithson loved me, and her regard was returned. Our attachment must be allowed platonic to a degree perhaps never before imagined, for Winifred has just attained the age of three years, while I am above three hundred. She is a golden-haired, sunny little soul, making all the music and laughter of her home. I am an old, grey ghost, to whom the western wing of Capon Hall has for fifty years been consecrated.

With an accident to the Squire’s daughter, Miss Ethel Smithson, upon some occasion of fox-hunting, this narrative properly begins. She suffered an awkward tumble, and the young man who came to her aid had the good fortune to please the girl immensely. Squire Smithson, upon the narration of Mr. Talbot Warren’s bravery, could not for the life of him see anything to make a fuss about. “If a woman falls into a ditch, is it asking much of the man nearest her at the time to pull her out?” he inquired. But Miss Ethel explained that the circumstances were of a very terrific nature, and how her hero, not content with seeing that she was safe and sound, had foregone all further sport, sacrificed his day’s pleasure, and insisted on riding with her to the nearest farmhouse.

She met Mr. Warren again soon afterwards, and continued to find peculiar pleasure in his society; while, finally, through mutual friends, the young man secured an invitation to Capon Hall for a week’s hunting.2For “Capon” the original reads “Capo.”

He and his horse arrived. He proved uninteresting, and a sportsman of mean capabilities; but Ethel Smithson, blind to the youth’s colourless and negative nature, fell violently in love with him. Being, moreover, a wilful little soul, who did pretty much what she liked with a most indulgent parent, matters went nearly all her own way from the start.

But the Squire and Mr. Warren had nothing in common, and, at times, their manifold differences of opinion might have produced serious results save for the younger man’s caution. Talbot’s physical nerve was weak, he wanted pluck—a lack that Mr. Smithson quickly discovered, and made the boy’s life a burden to him.

Ethel always supported the weaker side in the many arguments arising from this question of bravery; and, on one occasion, after the Squire had made some allusions more pointed than polite to his guest’s rapidly acquired knowledge of gaps, gates and like aids to the judicious Nimrod, Miss Smithson thought proper to drag me into the conversation.

“How can the wild, reckless courage you admire, papa, compare with the cool, mental nerve which may be shown to some purpose in the useful affairs of life? How many of the men who jump over hedges and ditches, and risk their stupid necks before the gaze of farm yokels, would sleep night after night in a haunted room, for instance, as Mr. Warren does here?”

“Our ghost!” roared the Squire. “Our little, plump, rolly-polly of a ghost! I’d make a better phantom with a sheet and a turnip!”3Rolly-polly: a podgy, plump, or stout person.

The man meant nothing; his remark was not intended offensively; but I chanced to be in the drawing-room at the time (on a little foot-stool by the fire), and I confess I felt hurt. People should be careful what they say in a haunted house. I have a friend, doing some haunting about half a mile from here, who would come over and punish these people horribly if I wished it. He belongs to the Reformation period, works between three and four in the morning, and, during that weird hour, can make a noise like china falling down a lift. But I am not vindictive. A phantom rarely reaches the age of three hundred without learning to control his temper.

“Physical bravery may be shown to greater advantage than in the hunting field,” said Mr. Warren, answering the Squire.

“It may, I grant you, but that is a right good school for it; and a man who loses nerve at a critical moment there will, in my judgment, be likely to do so all through his life.”

“Are there no brave men who do not hunt?” asked Ethel.

“Thousands, my dear. You give us a beautiful feminine example of begging the question,” answered her parent. “Moral nerve is, I allow, a greater thing than physical bravery at its best, but courage of both kinds, according to my old-fashioned notions, should be the hall-mark of a man.”

Talbot expressed a hope that some opportunity might ere long be given to him.

“I trust a chance of showing you I do not lack either one sort of bravery or the other will come in my way, Mr. Smithson,” said he.

Then the company retired, and, on the following day, private business took Mr. Warren to Hereford for an hour or two. He returned, however, before luncheon; and that night transpired the monstrous event I am now to relate. Although he slept in the apartment particularly associated with myself, I had not, I may here explain, vouchsafed an interview to our visitor, for reasons sufficiently sound. In my opinion, no good would have come of it. Mentally, Talbot Warren was not a coward; and the knowledge of this fact, combined with a certain underbred cubbishness in the young man’s treatment of inferiors, led me to suspect something derogatory to myself did I appear to him; but, after the recent conversation, I felt I had no choice.

As the clock struck twelve, therefore, on the night in question I made my way through the wash-hand stand in the “Russet Room” and stood before Talbot Warren. I am nothing by gaslight, and, to my surprise and irritation, Warren’s gas still burnt. He was dressed and sitting by the fire examining a huge lethal weapon with two barrels. He looked up and caught my wan, weird eyes fixed upon him.

“Oh, you’re the ghost, I suppose?” he said rather carelessly. I approached him and endeavoured to touch his brow with my icy forefinger, but he arose from his chair, regarded me insolently, and—I hate to write it—walked straight through me. I was never so put out in my life; I should have hardly conceived such a thing to be possible; I nearly choked with indignation. For sheer, unadulterated vulgarity, the man who intentionally walks through a ghost may fairly be said to stand alone. You tangible ponderable people who read cannot remotely imagine my feelings; but any spectre will. Revenge was my one idea.

Having, by this outrage, convinced himself of my unsubstantial nature, the little cad looked me up and down critically and contemptuously. Then said he: “You can’t upset my plans, anyhow.”

The knowledge that he had plans comforted me somewhat. That they were nefarious I gathered from the pistol which he carried; and that I would confound and outwit him at all costs I also determined.

Not until two in the morning did he prepare for action. Meantime, rendering myself wholly invisible, I sat on a chest of drawers and watched him. At the hour named, he shut his book, partially unrobed, put on his slippers, produced a “jemmy” and a dark lantern, picked up his weapon, and silently crawled downstairs.4Jemmy: a short crowbar used by a burglar to force open a window or door.

The hideous truth flashed upon me. He was one of some gang of burglars, and now intended throwing open the house to his accomplices! What was to be done? Our household lay buried in sleep. Warren stole to the butler’s room. Once within it, a stroke or two from his detestable apparatus would put the plate at his mercy.

For one brief moment I lost my nerve. The responsibility of my position was terrible. Then I strung myself to the struggle, and attacked him. But, in spite of my frantic gesticulations, aerial gyrations, and supernatural manifestations, the ruffian kept on his evil way unmoved. I dashed about, and tried hard to make him excited and impatient and worried, but he was as cool as a cucumber, and told me to “keep my hair on,” whatever that might mean. Then, realising the futility of this course, I sped away, faster than thought, to alarm the house.

Squire Smithson was slumbering noisily on his right side as I loomed through the fireplace of his chamber and laid an icy digit upon his brow. He leapt up instantly, but laughed when he saw who it was.

“Hullo, Fatty! Feeling lonely, eh? Don’t worry me, my boy, I’ve got a busy day before me to-morrow. Stick to your own room, and get a rise out of that booby Warren. If you can’t frighten him, you’d better give up the business and go back where you came from.”

Then he turned with his face to the wall, and was asleep again instantly. That is the world all over.

I went and woke the butler. I waved my drapery and pointed downstairs with actions that spoke louder than words. He sat up in bed and forgot himself altogether, and used language I shall not soil this page by repeating. It appeared that he was suffering from gout, and had only managed to get to sleep a few moments before I roused him.

“’Ere ’ave I bin torn to pieces with agony for three mortal hours, and just drop off, and then you come with your beastly cold paw and wake me and bring back the torture a thousand times worse than ever. I’ll give warning; I won’t put up with you and your tomfoolery for any master alive. Why should I? Get out of this room, you little brute. Don’t stand there waving about, like a shirt on a clothes-line. Go on, get out of it, or I’ll strangle you.”

I went. It was no good stopping. He couldn’t strangle me, of course; but it is impossible to explain a difficult thing like burglary, in pantomime, to a man who can hardly see straight for temper. I almost wept ghostly tears. Never before had the pathos and powerlessness of my position been so impressed upon me.

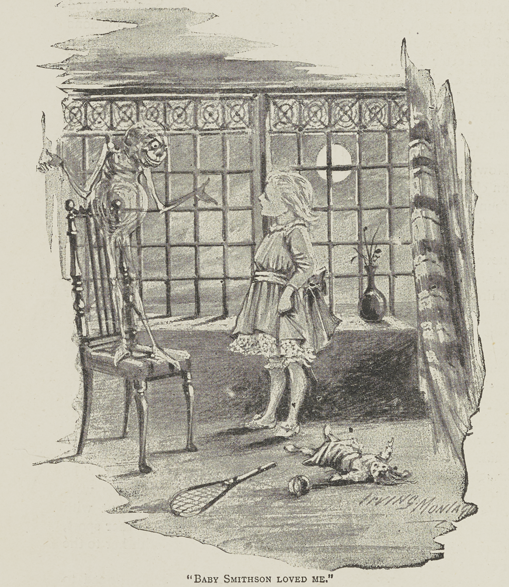

In this sorry plight I sought my little friend Winifred, the Squire’s grand-daughter before mentioned. She was lying wide-awake, silent and speculative as small children will. I loomed through a screen, covered with pictures from Christmas numbers, and she arose from her cot—a wee, comical white figure, faintly illumined by a night-light.

“How is you, dear doast?” she inquired.

My mystic presence always gratified her.

She chuckled and chirruped in baby fashion while I beckoned and moved towards the door.

“You funny old doast. Stand on ’oo little head, doast, like yesterday in de torridor.”

But I wasn’t there to fool. I wanted to get her out into the passage, then alarm her nurse and so the entire house.

“It’s too told to do walking to-night, doast,” she said.

“Cold!” I doubt if ever a phantom got up to such a temperature as I did on that occasion.

Then the nurse awoke, peeped two angry eyes over her counterpane and gave me some plainly-worded advice.

“Shame on you, ghost. Aint you got nothing better to do than scare childer and wake decent women folks. Be off with you, you old blackguard, or it’s a bell, book and candle I’ll fetch.” I only wished she would fetch a bell—and ring it.5Blackguard: a man who behaves in a dishonourable or contemptible way.

“Dood night, dear doast!” cried my small friend, as I sank through the floor into the footman’s chamber. Here further failure awaited me. I could not so much as wake the man. His was no natural sleep, but some species of loathsome hibernation rather, entirely beyond my power to conquer or dispel.

And downstairs the inexpressible Warren was filling a sack with choice spoil and drinking dry sherry from the decanter.

I dashed out of doors to see if anything could be done with the watch-dog, a massive brute, judged without sufficient reason to be ferocious. He was asleep, of course, but came forth from his kennel when I touched his nose, recognised me instantly, wagged his idiotic tail, and showed an evident desire to be patted. I couldn’t pat him, but I should like to have kicked him, and I’m not ashamed to say so. Never was a well-meaning apparition more justified in losing its temper than I on that hateful night. I tried to rouse the dog’s spirit; I threw imaginary stones, and frisked about and pretended to steal its supper; but the lumbering brute regarded me with that good-tempered glance bred from conscious superiority, and then went back into its kennel.

Warren had now taken his sack into the dining-room, had cut two window-panes out with a diamond (why, I could not at the time understand), and then, opening the window widely, lowered his booty into the garden. I fled out again to strike terror, if possible, into the hearts of his vile accomplices, but found, to my surprise, that there were none. Single-handed he was effecting his dark scheme.

Then a final desperate resolution came to my mind: I would rouse Miss Ethel Smithson herself, and show her the man she loved in his true colours.

Even then, my natural kindness of disposition caused me to hesitate. But if you see, as I did then, love’s young dream drifting into a nightmare, you are justified in shattering it. No burglar could bring true and lasting happiness into a gentlewoman’s life. That, at least, is my view.

“Why, ghost,” said Ethel, rubbing her eyes after I had waked her; “I don’t think it was kind of you to spoil a beautiful dream I was having about–but never mind, it won’t interest you.” I beckoned mystically, and she showed a little interest. I retreated, inch by inch, to the door, waving her after me. Hamlet’s father’s spirit never did anything better or more solemn and impressive. By all the curiosity of young ladies, she rose! She put on a dressing-gown and slippers! She said, “Whatever is it? I do hope there’s nothing happened to Talbot.” My heart bled for her, but I was firm, and she followed me out on to the dark landing.

A dim light flickered from a doorway far below. This Miss Smithson instantly observed, and deducing a theory therefrom with marvellous celerity, had the good sense to cry “Thieves!” louder than I should have supposed it possible for her to do so. Then she bolted into her father’s room, made the same remark, and finally retired to her own apartment, locking the door behind her.

“Alarums and excursions” were thereupon the order of the night, while the behaviour of the outrageous Warren passed belief. At the first sound of the tumult, he deliberately fired off his pistol through the top of his hat, and discharged the other barrel into a rather valuable hunting picture which hung above the sideboard. He then leapt through the open window into the garden, rolled himself in the mud, rose and galloped off into the darkness, shouting “This way! Follow me; I’ve got the scoundrels! Help here, help!”

I need not point out that these expressions were calculated to give an utterly false impression of the situation and circumstances. I had been grossly deceived, as the rest of the family were now about to be.

Squire Smithson came down the front stairs with a life preserver, and my hibernating footman rushed down the back stairs with another. The Squire kicked an umbrella-stand with his naked foot and stopped a moment to talk to himself. This gave the menial some advantage of ground, and when the head of the house reached his dining-room window, he found a man half way out of it. It was too dark to distinguish friend or foe, and Squire Smithson, making a dash at the figure, brought down his life preserver with considerable brute force. I cannot pretend to say I was sorry for this. The injured domestic screamed and was about to beg for mercy, when a mutual recognition occurred, and he contented himself with giving warning. Then they tumbled out of the window together and hastened to where great shouting arose from a distant shrubbery. A tramp, hearing the riot, got over the wall of the kitchen garden at the back of the house to help, and fell through the roof of a vinery. There he was ultimately discovered, cut to ribbons, and it took him all his time for an hour to explain his intentions. The dog, of course, began barking now as if he had known all from the first, and only waited the right moment; maids were screaming in pairs from different windows, and some fool in the house (the butler, I imagine) was beating the dinner-gong—doubtless to conceal his own cowardly emotions. For my own part, I was in twenty places at once, whirling through the dark air, issuing directions, explaining everything in dumb show, and making the entire concern as clear as daylight, but nobody paid the slightest attention to me.

Warren at length returned, breathless and bedraggled. He recovered with great apparent effort, gave utterance to a succession of dastardly falsehoods, and became the hero of the hour.

The scamp related how a noise had wakened him; how, seeing a light in the hall, he had crept downstairs, to find two ruffians with black masks lowering a sack of valuables out of the dining-room window; how he had hurled himself upon them with the courage of an army; how they had twice fired point-blank at him, and then fled; how he had followed them, seized one, and struggled with him; how, finally, they had succeeded in escaping from him.

And there was an end of the matter, for, of course, it appeared impossible to question the truth of the story, or raise any further doubt about the moral and physical pluck of a young man who could do these things.

Next morning the pistol was discovered in the garden; detectives wandered about, lunched at the Squire’s expense, found clues, and took the address of the tramp who had fallen into the greenhouse. This man had departed a physical wreck, swearing that he would never put himself out of the way again for anybody as long as he lived. And all because Squire Smithson did not see his way to recompense him for what he had done. The local paper published two columns of sickening adulation upon the subject of Talbot Warren; Ethel’s father consented to her engagement, and—bitterest blow of all—thought it proper and decent to publicly censure me at breakfast, before the servants, for the part that I had played.

“What’s the use of a paltry phantom that cannot even scare burglars away from a family mansion?” he asked.

“The poor little chap did his best,” said Ethel.

“Yes, after it was all over and the mischief nearly done. If he’d had the pluck of a mouse, he would have gone down to help Warren, instead of fluttering about making faces and doing nothing, and getting in the way. Why didn’t he speak up like a man?”

The brute Warren said he thought that most spectres were bad at heart, and the butler ventured to agree with him.

I am leaving Capon Hall. These incidents have knocked all the spirit out of me. I wish to say no bitter word of anybody; it is more in sorrow than anger that I write; but misunderstanding so disgusting, coupled with loss of self-respect so complete, can neither be lightly forgiven nor forgotten.

Change, repose, lapse of ages are all necessary to the renewal of my shattered moral tone and vital principle. It may be many centuries before I re-visit “the glimpses of the moon.”6From William Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” If I had my way I should never haunt again. In my case the game is not worth the phosphorescence. There obtains an idiotic belief among men that “all appearances are deceitful”; but that such a rule has many exceptions I can only trust this narrative will sufficiently prove.

Word Count: 4268

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Ainsley Dinger

Katie Sanofsky

Sarah Burlett

Kaylie Duckworth

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

8 March 2025

Last modified

3 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Locum tenens: a person who temporarily fulfills the duties of another. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For “Capon” the original reads “Capo.” |

| ↑3 | Rolly-polly: a podgy, plump, or stout person. |

| ↑4 | Jemmy: a short crowbar used by a burglar to force open a window or door. |

| ↑5 | Blackguard: a man who behaves in a dishonourable or contemptible way. |

| ↑6 | From William Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.