Beautiful Lucy Pierson: A Tale

London Society, vol. 2, issue 3 (1862)

Pages 223-232

Introductory Note: “Beautiful Lucy Pierson: a Tale,” fits perfectly into London Society’s light-hearted style because it is a story about a stunning woman who struggles to marry, and the silly—yet life-changing—decisions she makes along the way. London Society was written in an entertaining manner, yet many of the stories contain an underlying, serious purpose. This story is especially fitting because it approaches the important topic of marriage with humor, causing readers both to mock and mourn marital conventions.

Chapter I.

THERE was quite an excitement and an air of something being about to happen in the usually stagnant town of Clayton. There were groups of two, three, and four standing about in the generally deserted street. Mr. Slangroom, solicitor No. 1, who lived in a large house standing in its own secluded and rather damp grounds, on this especial afternoon stopped to shake hands with the daughters of solicitor No. 2 (who had to struggle hard to keep the roof of a modest small red brick tenement over his head) instead of passing with his customary crushingly condescending bow. In the open square in the middle of the town, around whose edge all the ‘best houses’ stood, the chief members of the female population were disporting themselves airily in summer garments of the latest fashion from London. The wife of the inspecting commander of the coast-guard district, the slightly faded but remarkably elegant Mrs. Jackson herself, whose claims to superiority would have been undoubted had it not been for the difficulty she occasionally laboured under about the correct distribution of her H’s—this lady, who would have loved to rule the whole town as she ruled the small naval hero her husband, who was in his turn a terror to the neighbourhood, through his peculiar method of driving the two ‘regulation horses’ government allowed him—this lady, I repeat, on this day of marvels, was seen to give her hand in a cordial and friendly manner to Mrs. Jones, the wife of the lieutenant of the station, whom, up to this auspicious day, she had always (at all events in public) kept at a distance. The surgeon’s wife, whose father had been a gentleman farmer, forgot to flout the rival surgeon’s wife, who had come a stranger to the place, and who had been unable to state precisely what her father had been. Every one seemed eager, anxiously happy, and slightly bewildered; and what it was all about shall now be told.

Just inside the turnpike gate which gave admittance to the town on the east, stood enclosed by high brick walls and secured from intrusion by massive doors, bolted, barred, and bound with iron, a large, square, substantial mansion. This was the rectory; and for many years the rectory had kept watch and frowning ward over that portion of the town, empty and deserted; for the shepherd of the flock at Clayton had been on the Continent for twelve years, and no curate was permitted to occupy his house.

The Rev. Thomas Pierson, some thirty years before the time my story opens, had been a rich young clergyman. The living of Clayton was in his family, so he came to the income it brought him without incumbrances of any kind. He had an established place amongst the magnates of the county in right of his profession, position, social qualities, and wealth. And soon the tie became stronger; for he married Miss Marchmont, the daughter of the oldest, poorest, and proudest baronet in the county.

For some years all had gone merry as a marriage bell with the Rev. Thomas and his aristocratic bride. The lady was seen on Sundays by her husband’s admiring congregation stepping daintily out of her carriage and along the aisle to her curtained pew; and occasionally, if any one was ill, and did not live in too small an alley for her pony-chaise to convey her to the door, she would drive up, and leave for the sufferer a basket of beautifully-arranged fruit and flowers. This was all that was known about her, and no one can affect to consider it aught but good as far as it goes.

In the course of years, four daughters stepped along with her up the aisle—religious little ladies, thought the people, for the youthful damsels looked not either to the right or left. But when the two eldest of these young ladies were grown up, and got invited to the houses of some of their father’s parishioners, and would not go; and when the surgeons, and solicitors, and wealthy merchants of Clayton found that their daughters did not get invited in their turn to participate in the many festivities that were going on at the rectory, the whole Pierson family were pronounced ‘abominably proud,’ and disliked with a heartiness that only people bent on pursuing the even tenour of their way, regardless of the attempts of others to thrust intimacies upon them, can experience. This being the state of affairs at Clayton, small sympathy was felt or expressed by the inhabitants thereof when one fine day the fact cropped out of the Rev. Thomas Pierson having got into such difficulties that a lengthened residence abroad would alone set him straight with the world again. He wrought, to be sure, a little on the hearts of his female auditors by the touching allusion he made in his farewell sermon to those ‘sons of mammon and unrighteousness who were distressing him and those innocent ones who were dependent on him.’1The allusion to mammon is from Luke 16:13. Two or three ladies resolved to call at the rectory in a day or two, and attempt to see and console Mrs. Pierson (she was a Marchmont after all) in her sorrow. In these days of her humility she might come down from her high estate and be friendly with them, and then they could speak of her afterwards to their friends as ‘dear Mrs. Pierson,’ and say, ‘how they missed her.’ But this was not to be. The following day Clayton was shaken to the centre of its being by a travelling carriage and four dashing out of the rectory grounds, containing Mrs. Pierson and three of her daughters, and laden with trunks. Later in the day, a fly from the principal inn conveyed away the rector and the fourth Miss Pierson; and in the evening the most distinguished inhabitants of the town received notes of farewell, with the Pierson crest on the paper and envelopes. And then no more was heard about them in Clayton for twelve years. But now a rumour, which had been vague and undefined at first, had gathered form and substance, and the report that ‘the Piersons were coming home again’ was an authentic one; more than this, their return was not a thing of the far-off future, they were coming home to-night. Even as one made this announcement to the other as they met and conversed in the open square it became an accomplished fact; carriages full of ladies and luggage passed them on their way from the recently-erected railway station to the rectory; and, peering anxiously into the last of these, the gratified inhabitants of Clayton had the pleasure of seeing the head of their revered rector rising above surging waves of crinoline.

The Piersons had been absent for twelve years, pursuing their plan of retrenchment; and how had it answered? It was difficult to discover, so difficult that it baffled the curiosity of Clayton entirely. The ‘county,’ their ‘own set,’ might know, but the ‘town’ remained, to its sorrow, in ignorance. The ladies of the place made friendly calls as soon as they could reasonably suppose the Piersons had had time to shake into something like order, but they met with a strictly parochial reception, and found out nothing save that the rectory drawing-room was furnished almost exclusively with what looked like the young ladies’ handiwork. The table-cloths had painted velvet borders, the chairs, sofas, curtain borders, were all of wool work; and ‘all this,’ said Mrs. Jackson, the naval commander’s wife, who had lived in a garrison in her early days, and been accustomed to see old boxes appear to the uninitiated as elegant ottomans through a little sleight-of-hand, ‘all this looked like making the best of nothing.’ One thing seemed certain—if the Piersons were just as poor as when they left, they were not one whit less proud.

The eldest Miss Pierson’s reputation had preceded her; she was a great beauty. The name of those foreign princelings and noblemen who had sought the hand of the lovely Englishwoman was legion; so at least said report: the only wonder was that, as all these aspirants had been so unexceptionable, she should have returned to Clayton ‘Miss Pierson.’

Lucy Pierson was unquestionably a lovely woman, for ‘girlhood’ had passed with her; a really beautiful woman of thirty, with every charm unimpaired. The soft, clear, pale brunette line of her face was as purely delicate as ever it had been in her earliest youth; the smooth brow was as unwrinkled, the deep lids, shading eyes of the darkest hazel, were as freshly full. And if Time, laden as his wings had been with many disappointments, fraught as he had been with many ‘forlorn hopes,’ had been kind to the face, so had he been in an equal degree to the form, of my heroine. She was still the perfection of symmetry: with the easy elasticity of youth she combined the rounded polished grace of movement as well as of limb of maturer years. Her face was very small, of a perfect oval, and as charming in expression as it was in feature. For almost any other face, the brow, exquisite as it was, would have been too low, but not so in this; none other, indeed, would have so well suited those rounded cheeks and that little chiselled nose. Her mouth was not of the full, passionate order of beauty; never a marble mouth was carved more coldly clear than hers. Statue-like as her loveliness was, Lucy had not the severe unsympathetic manner which usually accompanies it; on the contrary, the winning charm which surrounded her as a cloud was quite as attributable to the pleasing grace of her manner as to her wonderful beauty. And with all this, she had come back, after a lengthened residence abroad, to dreary Clayton, ‘Miss Pierson’ still.

Beautiful Lucy Pierson had come back to Clayton as lovely as ever, and most winningly did she receive and endeavor to entertain those ladies of the place who called to make them welcome; but not the less did she dislike the place, despise the people, and determine to change her position as soon as opportunity offered. Of the three younger sisters I have little or nothing to say; they were quite as proud, and far less pretty than their sister Lucy, and were comparatively very uninteresting. But they were amiable girls, and were quite aware that it would ill become them to think of marrying until Lucy was disposed of entirely to her satisfaction. Clayton was not the best place in the world to bring marriageable daughters to. The great people they had known previous to going on the Continent to retrench had died off, and their sons and daughters reigned in their stead, and these had forgotten the Piersons, or, if they had not forgotten, did not care anything about them. The present Marchmont baronet was only a cousin of Mrs. Pierson’s, and he first affected to be unconscious of their existence, and then, when they impressed it upon him, to be perfectly indifferent about it. Their connection with the Marchmont baronetcy would only serve them now to talk about. The Pierson family looked around them, and nothing was to be seen but desolation on every side, and then they turned their eyes on and looked at the town, and behold there was a break in the clouds.

About a mile from Clayton stood a pretty house—pretty despite its having a rustic porch on the west, and a verandah supported by some pillars on the south. It was surrounded by a sort of little park (they called it a ‘car’ in that county), well studded with trees, and of sufficient extent to prevent the two little lodges which stood at the extreme ends looking ridiculous. This house, and the six hundred acres which lay around it, was occupied by a gentleman of the name of Hunsdon, who held the property from the greatest nobleman and landowner in the county, the Earl of Warcester.

Mr. Hunsdon was a tenant-farmer, but essentially a gentleman-farmer. Not only had he a larger and more costly stud than his titled landlord, not only was his dog-cart the best built, his mail-phaeton the handsomest, and his dinners and hunt-breakfasts the best in that neighbourhood, and equal to any that could be given in any neighbourhood, but he was himself a well-educated, refined, handsome young man. Added to all this, he was very wealthy.

For three months after their return the Piersons steadily ignored Mr. Hunsdon and his politeness. Shortly after their advent he had called upon them; but the ladies of the family had merely bowed to him, and the rector had treated him with that elaborate civility one bestows upon people who have put themselves into the false position of coming when one does not want them. Mr. Hunsdon raged inwardly, and nearly broke the heart of his high-mettled horse, as he rode away that day, as he reflected on how he had been made to feel that they imagined him immeasurably their inferior. His rage was principally directed against Lucy; not that Miss Pierson had sat in the seat of the scornful above her fellows, but her beauty rendered her pride more intolerable to him than that of the others. He spoke very hardly of her to himself, and said to one or two of his friends that she ‘was just the kind of woman he detested;’ nevertheless he thought a great deal about the visit he had paid the Piersons in a weak moment, and chafed sorely under the nonchalance with which this type of ‘the woman he detested’ had treated him.

Now after the Piersons had taken that look around over their own ‘order’ which, as I said, showed them nothing but desolation, they held a council, and decided that it was their ‘duty’ to mix more with the townspeople and the immediate neighbourhood. They would still be king, queen, and princesses; but condescending ones. It was high time to do something; Lucy was thirty; the others were not standing still, fully aware as they were of their elder sister’s superior claims. On the horizon of their own world there loomed no prospect of a son-in-law; it was high time to do something; and no sooner did they recognize this necessity than they did it. They called affably on everybody who had eligible acquaintances, and Mr. Pierson sent out invitations for a dinner-party, Mr. Hunsdon being one of the earliest asked.

‘How he had mistaken that girl!’ he said to himself, after that dinner at which Lucy had flirted at him so cleverly that he had thought her reserved, and had prided himself on the skill he must have evinced to draw her out. ‘With such a mind, to say nothing of her manner, it was a small wonder that no man had been found worthy of her yet,’ he thought. In her matchless presence the handsome young man, who was usually so thoroughly self-assured, felt humbled, diffident, nervous; but Lucy was very kind, nay, more, most encouraging. He was not a coxcomb, but he began to dream of this peerless scorner of foreign princes and others as his wife. He was dazzled, enchanted, very much in love. Lucy thought of what she had heard were his prospects (in a year or two he was to come into possession of an estate his father had just purchased); she thought of the many comforts and luxuries his wealth would enable her to enjoy, of the struggle life at the rectory was, of her own thirty years, and of the microscopic chances that were in favour of anything better offering. Hunsdon was gentlemanly, sufficiently clever, remarkably handsome, and his being very much younger than herself would be her excuse to the few grand acquaintances, who might trouble their heads about it, for her having been flattered into the match.

She told him she ‘adored a country life, admired cows, and thought his place, Bexley Grange, the prettiest in the neighbourhood.’ He doubted her as regarded a liking for the country life, totally disbelieved her about the cows, and knew very well that the Grange, though a pretty place enough, was far from being the prettiest in the neighbourhood. But he saw that she wanted to please him, and that was all he cared about. He was a thorough gentleman, and meant the love he looked; and of this Lucy felt so well assured that she began considering how many dresses she would want to start with as Mrs. Hunsdon, and what their colour should be. And he looked into the refined and beautiful face of the lady, and thought how far superior she was to the mortals by whom he had been hitherto smiled upon, who had doubtless had a keen eye to what he possessed. And so for a few weeks all went on smilingly under the glorious summer sun, and Mr. Hunsdon strongly constrained himself not to be precipitate and so alarm the sensitive delicacy of the queen of his soul. Many times during these summer days the rich, happy young tenant at the Grange had the honour and felicity of entertaining the Rev. Thomas Pierson and a party of his hungry friends at sumptuous luncheons, at which the heart of the worthy rector was gladdened by the free flow of that wine of the south which he well loved; and the lovely Lucy was good enough to go and eat his peaches, and the lovely Lucy’s mamma was good enough to accept as much cream and butter as he liked to send her, and to be gracious and merciful generally to the young man; and Mr. Hunsdon’s favourite mare began to loathe her life now that so many hours of it were spent in the damp, fusty, cheerless stables of Clayton Rectory. And just as Mr. Hunsdon had completed sundry arrangements he deemed it incumbent upon him to make before proposing to this granddaughter of the Marchmonts, a little cloud arose.

I have said that the largest landowner in the county was the Earl of Warcester. His principal estate lay near to Clayton, and being a great agriculturist here, he had a model farm, with elegant pillars supporting his cow-sheds, and marble mangers, and glass milk-pans, and little paths leading from one building to another all done out into beautiful patterns with little pieces of red brick, white flag, and gray slate.

The gentleman who managed this model farm was the earl’s lawyer and agent for all the estates he possessed in the county, and as this did not afford him full occupation, he took young men, who had nothing else to do and had not made up their minds what path in life they should eventually pursue, into his house as farming pupils. Two new ones arrived early in September. Clayton was only a mile or two from the model farm. They had nothing to do. One, the Hon. Mr. Newman, was the younger brother of an earl; the other, Mr. Lewis, was the only son of a rich commoner. They were very young (neither of them had seen two-and-twenty summers), very idle, and very much given to despising every one around them. It chanced that they met and got an introduction to the Piersons; they heard that the only man in the neighbourhood who was not desirous of cultivating their acquaintance (when they met at the markets they occasionally honoured with their presence) on other than equal terms, they heard that this man was in love with the beautiful Lucy, and immediately the lofty desire of cutting him out fired their noble minds. Miss Pierson was at once alive to the superior advantages they could (either of them) offer her. She was far kinder to them than she had ever been to Mr. Hunsdon, for it was a greater tax on toleration even to listen to them, and Mr. Hunsdon found himself dropped by the whole family, from the portly, bland rector, who had grown even more sleek at those frequent luncheons at the Grange, down to the scrubby little boy who had so often wounded the heart of the mare by leading her away to the bleak stable. In the course of one morning call at the rectory, Miss Lucy caused the waters of mortification to overflow his soul. She ‘condescended’ to him before the two boys whom she had made his rivals; she affected to endeavor to suit the conversation to his line of life for a few minutes, and then with a weary air she turned from him and really strove to talk fashionable jargon to the two youthful members of the aristocracy who were attempting to stare Mr. Hunsdon into a state of confused humility.

I have stated that Mr. Hunsdon was no coxcomb; more than this, he was no fool. In the short half-hour, the last he ever spent with her, he read her character (or want of it) far more clearly than he had done in all those weeks of admiring intercourse. He saw through her now—an interested, heartless woman, with a keen eye to the main chance and the face and form of an angel. He read her thoroughly, and she saw that he did so, and feared she had gone a little too far in dissolving his illusion ere she had secured another. She knew as he took her hand for one moment in his, in cold farewell, that it was all over. She thought of the many times success had nearly crowned her hopes, but not quite; she thought of her thirty years, of life at Clayton, and she sighed as she turned to the richest and apparently the easiest to beguile of the two farming pupils, Mr. Lewis.

He was not an enlivening object to contemplate; a very tall, slightly round-shouldered young man, with cold gray eyes, a smooth pale face, and a close-cropped, bullet-shaped head. His face was not devoid of expression; a profound conviction as stamped there in insolently legible characters that he was immeasurably superior to everybody else, his friend Newman excepted. He was arrogant, conceited, half-educated; but such as he was Miss Pierson intended (dare I say so?) to stalk him. Mr. Newman was simply a heavy young man with a rubicund face. Miss Pierson wasted few thoughts on him, for he had nothing but what it pleased the earl, his brother, to allow him; whereas Mr. Lewis had nothing between himself and the actual possession of great wealth save a weak old father, who always allowed him to do as he liked, and whose estates were strictly entailed on this bullet-headed son.

Mr. Lewis was the more eligible of the two, and Mrs. Lewis Miss Pierson determined to be.

Chapter II.

It was astonishing, considering how haughtily she must have deported herself to the foreign princes and nobles, to witness how assiduous Miss Pierson was in her endeavours to please this remarkably plain English gentleman. She spared no pains, and she won, or nearly won, the day. Mr. Lewis lost his head, and forthwith imagined he had lost his heart; but being a youth of a lethargic temperament, he put off asking her to marry him ‘because,’ as he observed to his friend, ‘he knew he could have her any day.’ And in the meantime he contented himself with riding in to call on her three times a week; eating the top of his riding-whip at her for half an hour, and calling a little black toy terrier he had lately purchased for the purpose ‘Lucy.’ All this was well, but the whole Pierson family felt that it would be time and patience thrown away should matters rest here; so they waited anxiously for his next step, and in time he made it.

The one subject Mr. Lewis could enlarge upon was riding, and on this topic he had discoursed learnedly, at great length, and frequently to Miss Pierson, who knew nothing and cared less about it, but who had carefully concealed both her ignorance and indifference. Now, however, he made a proposal; not the one she wanted, but one that under the circumstances required almost as delicate treatment. He proposed that Miss Pierson should ride his mare Sunbeam. She got out of the difficulty at first by stating how impossible it would be for her to ride with him alone—she would not venture upon telling this admirer of female equestrianship that she disliked and dreaded the idea of mounting a horse; it would be time enough to make him fully understand that when he was her husband, and it would not matter whether he was pleased or not. But on this unlucky occasion Mr. Lewis showed himself prolific in resource. He could provide a very tame cob for her father, who could then accompany them. ‘Newman would go with them,’ he added, ‘so her father wouldn’t be in their way.’ After this, what could Lucy do but improvise a habit and profess herself ‘delighted?’

The day came, and with it the mare, the cob, and the two gentlemen on their strong, fast hunters. Miss Pierson stood on the doorstep with a smile in her eye and dire uncertainty in her heart as to ‘how she was to get up on that horse’s back,’ in the first place, and ‘how she was to stay there,’ in the second. She looked very beautiful, though, and so Mr. Lewis thought as he drew off his glove and stood ready to lift her up.

Lucy approached her steed praying that he would unintentionally let fall some hint which would guide her as to ‘what she should do next;’ but as she only felt and did not look embarrassed, Mr. Lewis remained in happy ignorance of her uncertainty. Through a stroke of special luck she gave him the foot she ought to have given, and the next moment she was safely in the saddle. ‘Now,’ she thought, triumphantly, ‘as the horse is so quiet, he says, the worst is over.’2Comma added after “says” for clarity. Alas! her miseries had but begun.

A complicated mass of reins was put into her hands, and seeing she looked slightly bewildered, Mr. Newman kindly suggested, ‘Ah! You’ve been used to a single rein, I suppose.’ Lucy smiled at him and said, ‘Yes.’

‘You’ll find she pulls a little,’ explained the owner of the mare ; ‘but if you give her her head she will be all right.’

Lucy patted Sunbeam’s neck, and said, ‘Of course she would.’

Her three cavaliers were mounted by this time, and with a nod to the anxious group who were watching her from the drawing room window, Lucy started on her perilous journey.

All seemed to be going on well. Sunbeam stepped along daintily in a quiet walk by the side of Mr. Lewis’s horse. Lucy began to think riding ‘very easy indeed.’

‘Do you like trotting?’ asked Lewis, as they turned off into the high-road beyond the turnpike gate.

‘Ye—s,’ replied Lucy.

‘Come along,’ he said, drawing his own reins tighter as he spoke. Instantly Lucy felt as if she was being cast headlong into the road, and then the mare threw her head up wildly.

‘Slacken the curb,’ roared Lewis. ‘She’ll be over with you!’ and as he enforced his directions by seizing the reins himself, she came safely out of the first little difficulty (which had been occasioned by her having administered a series of jerks with both hands to the bridle) and found herself still in the saddle.

‘Sunbeam pulls a little,’ said her owner, with a reproachful cadence in his voice that rang on Miss Pierson’s heart mournfully; ‘but you needn’t take her on the curb like that, Lucy; you must humour her. The more you pull at her the more she’ll pull at you, and if you tease her too much, she’ll get away. Draw your snaffle tighter when we start again, and only let her feel the curb when she gets too fast.’

These were excellent directions, no doubt, but a slight drawback to their answering perfectly existed in the fact of Lucy’s not knowing which was the curb.

‘When you once get into her way,’ continued Mr. Lewis, ‘you will say she’s the finest trotter you ever mounted. Come along.’

Lucy grasped her reins convulsively; Sunbeam’s head came up with an angry toss; through Lucy’s mind darted the remembrance of what he had said about Sunbeam ‘coming over with her,’ and of the necessity there was for her not to ‘bear upon something’—she wasn’t clear what. She let the reins flap against the mare’s slender neck, and the next moment her agonized parent, who was suffering much through the agency of the cob, saw his daughter fly off at a pace that afterwards entirely baffled his attempts at describing.

‘She’ll break her neck!’ screamed the father to his companion, Mr. Newman.

‘No, no; she won’t do that,’ replied the gentleman; ‘but she may bark her knees. I fancy that’s what Lewis is most afraid of.’

It will be seen that the gentlemen were alluding to different subjects.

The road was straight for some distance, and then it took a sharp turn. Mr. Lewis could not hope to save the lady, whom he perceived was hanging on somewhere about Sunbeam’s neck, but he did fondly hope, by striking across some fields, to intercept his mare before she received any injury. The hope, moderate as it was, was not realized. At the turn of the road Miss Pierson came out of the saddle, and was deposited upon the turf lightly, gracefully, and unhurt; but, alas! when the master of the mare contrived, through some very reckless cross-country riding, to stop that precious animal, he found that the reins had got entangled with her feet and had caused her to fall and severely graze her knees. As he wiped the gravel off poor Sunbeam’s wounds he resolved that a lady who had been so regardless of his dearest interests should never be his wife; and when he slowly and sulkily rejoined the party, leading his once matchless ‘fast trotter,’ Miss Pierson read in his countenance that ‘it was all over in that quarter.’

‘I tell you what, mamma,’ she said, when she had returned home ignominiously on foot about an hour after she had started apparently so bravely, ‘I’ll tell you what, mamma—it’s no use, I feel sure of that, wasting any more dinners on those dreadful boys. Lewis would scarcely speak to me all the way home; and though I told him my wrist was hurt I could not even gain sulky sympathy from him. Really,’ continued the young lady, looking at her swollen hands, ‘what I have to put up with tries me too much.’

‘And so beautiful as you have been and still are,’ replied her mother, sadly; ‘and so well as you might have married, Lucy! How is it?’

‘Because I’ve always tried, and have been urged by you to try, for “something better,” mamma,’ answered Miss Pierson, scornfully.

‘Well, never mind, dear,’ hurriedly interposed her mother. ‘We will see about being civil to Mr. Hunsdon again.’

‘I don’t think that will be any use now,’ said Miss Pierson. And she was quite right; they tried it, and it was of no use.

Heavily sped by the days, weeks, and months at Clayton Rectory. Those who only saw the bland, hearty rector in the ‘parish,’ where, being a benevolent man, he moved about like a great, genial, generous, florid spirit of relief, would have found it difficult to bring the picture before their mind’s eye of what he endured under the shadow of his own roof-tree and on the sanctity of his own hearth. Poverty and privation and a constant endeavour to make the best of things and both ends meet had told on the health, temper, and spirits of his wife; when she was not actively irritating she was passively morose. She had borne a great deal uncomplainingly, to her credit, be it said, while there remained a prospect of ‘something better’ for her children; but the vision of this ‘something better ‘ had been waxing fainter and more faint of late years, and the more eagerly they had tried to grasp it the more had it eluded them; and thinking sadly of what would be their future, full of great love and fear for them, she rendered their present almost unendurable by a constant system of nervous ‘nagging.’

Lucy, the bright, beautiful daughter, of whom her father had been justly so proud, was falling into the sere. She, too, had been subject to trials which had told on her health, spirits, temper, and at last on her beauty. She had nothing to look forward to but a life of monotony at Clayton, and she began to be arid to the younger sisters, who, never having enjoyed much sunshine as had fallen to her lot, bloomed better under the present bleak aspect of affairs. She felt, too, that she had been ridiculous in that matter of the ride undertaken at peril of life and limb under Mr. Lewis’s auspices, and being angry with herself did not increase her amiability to the rest of her family. This being the state of the case, Mr. Pierson, as was natural, hailed the arrival of a brother rector, who was just now appointed to the living of Alderly, the next parish to Clayton, with joy deep and unfeigned. For the new rector, Mr. Farquharson, was a widower, childless, well off, and, report said, not at all unwilling to enter into the bonds of matrimony a second time. Mr. Farquharson was one of those little roundabout men with fat, smiling faces that you meet every day; he was hopelessly mediocre. Mr. Pierson muttered in confidence to his wife that ‘he was a prig.’ However, neither Time not Lucy would stand still. It was a terrible fall, to be sure, and the parents’ hearts ached as they gave their consent, thinking ‘of what might have been;’ but it seemed as if such a sacrifice was to be consummated, for when the plump widower proposed to the beauty she accepted him, and the marriage was arranged to come off shortly.

In this kind of stories the lovely heroine nearly always offends the tenacious dignity of her orthodox lover at a ball: this unfortunately was the case with Lucy. The officers who were garrisoned in the cathedral town of the county gave a ball. At this ball appeared for the first time since his coming to the title a young baronet, Sir Digby Tilden. Lucy’s charms wrought powerfully on one of the softest hearts (and heads) ever youthful baronet owned. The still exquisitely beautiful woman, flushed with her triumph, which was very apparent, flouted her reverend lover. He was meek and long-suffering, and came to her the next day, offering, if she would fulfil her pledge and give him her hand, to say no more about ‘that conduct of hers last night, which had’ (to say the least of it) ‘been so very painful to him.’ She tried to be honourable, true, faithful, and womanly for once, but she thought of some sentences of more than admiration which had escaped Sir Digby’s lips; she thought of his request that he might be allowed to call; she thought of his Hall and rent-roll, his title and position; and she could not be other than true to herself and false to Mr. Farquharson. She broke the chain that bound her to the clergyman and waited impatiently for the appearance of the baronet.

He came once, and only once. A younger, though not a lovelier star had attracted him now, and the idle words he had uttered, which had caused Lucy to quit her hold of the straw she had clung to, were idle words indeed. He married her youthful rival about the same time that Lucy’s third sister took pity upon Mr. Farquharson, to whom Lucy was about again to offer her perjured hand—as delicately as she could.

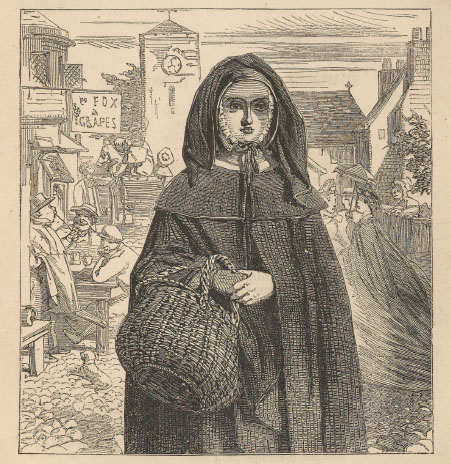

She stayed at home until two of her plain young sisters had gained husbands to love and care for them, homes to care for and grace, until her waning beauty was the constant theme of regret and commiseration amongst all about her. And then she hid her faded loveliness and her baffled hopes and blighted aspirations under the plain, sombre garb of a ‘Sister of Mercy,’ and left for ever the pitying tongue of scandal at Clayton to wag at its own sweet will about Lucy Pierson, the rector’s beautiful daughter.

Word Count: 6311

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Annie Hall Thomas. “Beautiful Lucy Pierson: A Tale.” London Society, vol. 2, no. 3, 1862, pp. 223-32. Edited by Paige Torgerson. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 18 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/beautiful-lucy-pierson/.

Editors

Paige Torgerson

Tyler Vogelsberg

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

29 September 2016

Last modified

18 July 2025