Blind Love

The Pageant, vol. 2 (1897)

Pages 64-81

Introductory Note: “Blind Love” follows the romance of a knight and a princess, cursed by a fairy to be forever invisible unless she “plays the wanton,” or scandalously loses her virginity. This fairy tale explores a woman’s responsibility to maintain her chastity, something that early Victorian society linked directly to a woman’s value. In the final years of the Victorian era, however, many of society’s customs were questioned and scrutinized; this tale is no different, introducing a conflict between being beautiful and being chaste.

HOW shall I tell this gentle story so that they who read may not weep too much for the sorrows that are told therein; for, indeed, none must grieve too greatly, seeing that all comes to a good ending.

This is how a king’s love for his wife, and the faithful worship he kept for her, brought great pain to them both, by the working of one fairy’s malice, which I shall now tell you of. This king, whose name was Agwisaunce, had to wife a queen whose beauty was to him as a veil hiding from him the fairness of other women. No eyes drew him but hers, nor did the sweetness of other lips seem to him a taste worth having. If I began, I could not finish telling all the tenderness their hearts had for each other. But though their love ripened from year to year, no fruit of it came to them.

After they had been married many years without children, there chanced, one day, into the court of that realm, a fairy possessing great sleight of magic, and such beauty as was not safe to look upon, so piercing were its effects. And she, being received at the Court with much honour, was stricken presently with an uncontrollable passion for the King’s person. Such grief falls but seldom to the finer nature of which fairies are moulded; yet, when it comes, it strikes down mortally into the roots of their being; nor can they rest till fate has made accord with their desire.

So it was with this fairy whom love for King Agwisaunce lowered to the very dust of humbleness. Though she traced and traversed to get the better of his heart, never once could she win him to turn on her the amorousness of his eyes, or to pretend knowledge of that to which she aimed. Till at last there came a day when in plain words the fairy made known to him her wound, and Agwisaunce, for his part, gave her a downright refusal for answer. ‘I think shame,’ said he, ‘that a great fairy, such as thou, should seek to come between the love that two mortals bear in constancy and pure trust each to other!’ So at that the fairy parted from him without more words; and he, believing her gone, put thought of it away in secrecy and with a light mind.

But that same night Agwisaunce, in the barred solitude of his own chamber, and nigh upon slumber, felt lips that he deemed to be those of his own wife coming and going over his face, and he turned to do honour to her visit in fair amity. Yet he thought within himself, ‘Why does she not kiss me as we always do, in the hollow under my right ear?’ For that was the way these lovers had—a token of things since they were first wed.

Then he lifted his hands to the face that was by his, saying, ‘Verily, is it you, beloved?’ And at that came more kisses, but no answer. Then the King thought, ‘Now, if I kiss her not in the hollow under her right ear, and she ask it not of me, I shall know that there is some estrangement come betwixt her and me.’ So then he kissed her between the brows and in no other way; and the other made no complaint at that, only kissing him the more.

Then Agwisaunce rose up, wondering, and made a light to know what plight he was in; yet, when he searched, all the couch was empty—none could he see. Then he passed to his Queen’s own chamber, and found her sleeping fast. ‘Truly, I have been deceived!’ thought he, and returned to lie down. But so soon as he was stretched out at full length again, he felt by his side one that kissed and caressed him without ceasing.

So, at that, Agwisaunce, making an end to it, pushed his bed-fellow from him, saying, ‘This is not my own Queen, but some other!’ Then softly the fairy’s voice spake to him; but he, as not hearing her, cried, ‘Go out, thou great light o’ love! Art thou not ashamed to follow me thus?’ But she: ‘Where I have love I have secrecy, but no shame. Lie down and do my will; thy wife shall not know. For none saw me entering, neither will any see me return. Even as I was to thee when thou camest in with the light, so have I made myself invisible to mortal gaze; and where no other can be wise, it is well for thee to be.’

Then Agwisaunce was up in great wrath; and said he, keeping her out from him at arm’s length, ‘Is not the rest enough, but thou must take thine invisibility as a cloak to thy foulness, and come in by stealth to play the wanton between me and my Queen!’

At which the fairy, seeing that she was not to prevail, cried back on him with fury, ‘Ah, virtuous one, now even as thou hast reviled me with shameful words, so will I pay it back to thee again! It is news to thee that even now thy Queen is with child; and of that there shall come a daughter to be a thorn in the side of her parents: for from the hour of her birth she shall be invisible, and so shall she remain till she also play the wanton. And when she shall have played the wanton, then shall that spell be taken off her, and thou shalt see the face of her shame and the shame of thy house, and be sorry at last for the scorn of thy words this night!’

Then the fairy departed, and King Agwisaunce lay down with great trembling, and watched till it was morning.

On the morrow the Queen, beholding his mournful countenance, and his gaze ever at her girdle, wherein he beheld sorrow now grow, besought him by all his love to tell her wherein life ailed for him. Then little by little she drew out from him a part of that story; but on one part his lips stayed dumb, only said he, ‘There remains one condition by which the spell shall be loosed and our daughter given to our eyes; but as to that, pray that thou never have reason to behold her face! Rather ask Heaven to keep her as she is born.’ And when the Queen asked him what it might be, he answered, ‘If I told you so much, straightway your pains would seize you and the child die, born too soon for life to be in it. Never ask me to tell you that!’

So, not many months after, the Queen’s time came for her to be delivered; and she wept bitterly over the thought of the child that was to be born like a ghost out of her womb, nor ever to bless her eyes with its beauty for a solace to all her sorrow. Presently there was heard in the palace the cry of a new-born babe; and those that were in the chamber, hearing the cry but beholding nothing, knew that the curse had fallen: for all knew that a curse had been foretold on the birth. But none save the King and Queen knew the cause of it, and only the King by what way to be rid of it.

The King reached out his hands and took up into them the invisible life that struggled and wailed sadly at being born; then the mother, clasping her child to her breast, felt it over from head to foot, and, even as she wept for the useless longing of her eyes, declared that no child so perfectly formed, from the dimple of its head to the cushioned soles of its feet, had ever before been born into the world.

After that came the christening: never was so strange a one since time began, for the priest could not see the babe he held, and had she fallen from his arms she might have been drowned past finding. The whole Court drew a breath of relief when she was given back safe into her mother’s arms, bearing the name of Innygreth.

With what trouble and losings and findings again her babyhood was passed, it would be wearisome to tell. But before long the Princess took her life into her own hands and shaped out her own fate. For from the moment that she could walk she became the most surprising and perplexing of charges. Here one moment, she was gone the next, and unless it were her royal will to let sound go forth of her whereabouts, she was more lost to mortal reach than a needle in a load of hay.

But gradually, as babyhood wore off, she became gracious and kind in her way, yet sad that she had no other children to play with. At times they would hear her stop in her walk before one of the great mirrors of the palace, and there stand whispering softly to herself. But whether what her eyes saw were her own image or no she would never tell.

All that her touch rested on and warmed became invisible as herself. Her clothes and all the jewels and feathers that were put upon her, warmed by her body, passed out of sight.

Slowly her mind grew in gentleness and grace of her own choosing. That her presence might be known, she took to bearing always in her hand a lighted taper. And all the taper, when her fingers closed on it, became invisible as her dress; but the flame, since she did not touch that, burned clear. So wherever a light went travelling about in mid-air the courtiers knew that Princess Innygreth was in its company.

On her tenth birthday the Princess came to the Queen and said, ‘Beautiful mother, would it not gladden thy heart to see only a little part of me, of whom for ten years thou hast seen nothing?’ ‘Oh, my Beautiful, fate holds thee, and I cannot!’ replied her mother.

Then Innygreth, reaching out her hand, loosed from it something that shone as it fell into the Queen’s lap; for as soon as she loosed it out of her hand it became visible. And the Queen saw there a great pile of golden hair that shone like fire, which the Princess had cut off that her mother might learn how beautiful she was.

The Queen laughed and cried with joy, as, for the first time, her eyes were blest with the sight of a small part of her daughter’s loveliness. And even more did Innygreth herself cry and weep. ‘I have given you all of it,’ she sobbed, ‘because I love you so!’

As the Princess grew older she became very wise. ‘Where do you learn all these things?’ asked the King. ‘You do not read many books.’

‘I blow out my light,’ said the Princess, ‘and I learn things as they are, and not as princesses are used to be taught them. I know many things that you do not. Some day when I know more I will teach you how to govern well.’ The King laughed at that; but the Princess was grave. ‘To me,’ she said, ‘all the world is like a glass: I see it, but it does not see me.’

Now, as soon as the Princess drew near to the age for marriage, the King began thinking that to have her roaming free, fluttering the downy wings of her unguarded virginity, was a tempting of God’s providence. Therefore he began scouring the world to find a fit suitor for her hand.

Many came, indeed, to the Court, drawn by the story of her marvellous manner of life, her great wisdom, and possible beauty; but though all were won by the charm of her voice, they dreaded that peace with honour could not come in the possession of a wife over whose doings only the eye of Heaven could keep watch. Some, indeed thought that the spell under which the Princess lay was friendly to her fortunes and a trap to the unwary, and that her invisibility concealed a hideousness which marriage alone would reveal.

One and all the suitors retired with polite elongations of regrets and the King fell to breakfasting on despair; and a trepidation lest his daughter should one day swim scandalously into view before the eyes of the whole Court caught him in the small of his back whenever he opened a door or turned a corner.

Now, there was then serving about the palace a youth named Sir Percyn, he being a lieutenant in the King’s guard, and a fellow of most merry wit. All things he did came so gladly off his conscience they had the apparent seeming of virtue. As for his virtues, he cloaked them in such waywardness that men, having to laugh, forgot afterwards to admire. Were he to do any bravery, he covered it by a wager; or a gentleness, he did it by a jest. But the Princess, passing unseen and unknown out and among the precincts of the court, saw Sir Percyn when he wist little who looked at him, nor was making capers to conceal his cherubimity.

It was not long before Innygreth favoured him wondrously, and, with maidenly reserve blowing out the light of her presence, lingered daily in his company, warming her regard for the one man who was the same, whether before kings or behind them.

Now, Innygreth, being so sheltered by her birthright, at once from the assaults and the safeguards men make on womanly innocence, whether to foul or to foster it, had great knowledge of many things that are shuttered from the eyes of most maidens. Therefore she was honest without confusion, and had modesty without fear; and having had no shame for her own body since the day of her birth, had no shame of it in others. Also rank she saw below and over; truly between the crowns that bowed and the crowns that were bowed to, it seemed a little space to her.

Thus she passed down through all her father’s court, from the men of state till she came to the lower grades where Sir Percyn made gay—a light of March-moon madness round his head; and there she stayed and searched no further, having found the unit of her thoughts.

As one learns to love the south wind when it blows full of the breath of flowers, though one sees it not, so Sir Percyn grew in love with the toils of her sweet voice. So much he loved her that in a while she lost with him her power of stolen marches, and came she never so silently and with no light, still he knew her to be there, and the colour would run to his face to meet her as she came. All may guess how after that she knew that her heart held its wish.

For three days she let him go sad, but after that she could no longer withstand the springing tenderness of her love. That time she put her hands about his face, and let word of it go. ‘Thou loon, thou loon!’ said she; ‘why ever dost thou not speak?’ And quoth Sir Percyn, trembling between great joy and sorrow: ‘Speak what, thou eclipser of mine eyes?’ Innygreth answered, ‘Truth only, thou moon of madness! Nay, nay! to be ashamed for loving me so well!’ And before he knew what more not to do, her invisible heart lay knocking at his side, as wanting to get in.

Then he, thinking of all her height above him in the world, and the gulf that sovereignty and power made betwixt her and him, held her the more closely for that, and out of hopelessness grew bold; and he cried out in anger and exultation, ‘Nay, now I have thee, I will never let thee go!’ She laughed for pure pride.

‘Between us,’ she said, ‘is a great gulf fixed that no bridge can cross.’ ‘Our love fills it,’ he answered; ‘it carries us.’ ‘To what shore?’ she asked him. ‘To thine or mine—it is all one,’ he answered.

‘Thou knowest me,’ said Innygreth; ‘wouldst thou see my face?’ She took his hand and laid it over her unviewed features. Her knight thrilled to feel the loveliness that lay there. ‘Tell it me,’ she murmured, ‘for till now I have heard no man praise my beauty.’

Sir Percyn, moving his hand as a blind man that reads, said: ‘Thine eyes drink the light as the deer drink up the brooks. Thy lips are a rose-garden where the rocks make echoes; thy cheeks are a land of blossoming orchards; and thy brows are the gates of heaven. Though I have not seen thy face, now I know it, for my love has filled the gulf and carried me through to the Invisible wherein thou dwellest.’

Now, none need tell what lovers say when they have once said all, nor how often, if they have means, they meet. Between Innygreth and Sir Percyn there began to be long meetings and partings, and the Princess, being free from the bonds that hold others, was like moonlight and sunlight about her lover’s ways.

Often at the dead of night she would come into the chamber where he lay, and sit watching him asleep, or, waking him, would hold his hands, and, till pure darkness fell before dawn, music to him with her sweet voice. And Sir Percyn, beholding in his lady a modesty without fear and a trust that dreaded no shame, became afraid with the great bliss of the love that heaven allowed, and trembled daily while she drew him to the heights of her own nature, that, having so much love, had no room for guile.

When he was on guard by night at the palace, he would wait below the roses that climbed to Innygreth’s chamber, and if she waved her light to him, then he was up by flying buttress and carved moulding among the reddest of them all, hanging across the window-sill, and embracing Innygreth in his arms. Many and soft then were the words by them spoken; but a sharp-eared crone that was put by the King to be about the Princess caught some sound of them.

She came and whispered to the King how at night there was the sound of a man’s voice in his daughter’s chamber, and chirpings like birds in the leaves about the window—so many that she trembled and lost count of them.

Agwisaunce, when he heard that, took so large a panic that he stooped down his pride, and night by night hid himself in the arras of Innygreth’s chamber to learn how near might be the undoing of the honour of his house. And, surely, on the third night he heard the Princess move out of her bed, and through the window the sound of one climbing the wall without, and presently kisses so many and passionate that, fearing what next might have place, he leapt forth, crying out on his daughter for a wanton. At which word one blow caught him and laid him down for a while prone and speechless; for Sir Percyn, hearing the honour of his fair love slandered, and knowing not that it was the King, fetched Agwisaunce so full a buffet that the thing became high treason. And betwixt this and that, Sir Percyn’s head was forfeit by the time the King had recovered consciousness.

So the next day all the Court heard how Sir Percyn was under arrest to be tried for an attempt on the King’s life and honour. Nor through all incredulity and bewilderment did any get nearer to the truth than that.

But now more and more the King was seized by a horrible fear lest some fine morning he should find his daughter made visible before his eyes, and her bloom and reputation flown from her like the raven out of the ark. ‘Already she goes the way of a wanton,’ he said, ‘and that is a short road with a quick ending. Though walls have ears, for her they have not eyes. How shall I keep her, then, so that I be not presently shamed in my own palace?’

Now, even while he trembled over his daughter, so contagiously disposed towards her fate, there fell to him, like a star out of the lap of Fortune, a suitor for the hand of Princess Innygreth. The Prince of a neighbouring country, amorous with curiosity for the wooing of invisible loveliness, sent word asking for the hand of the Princess in marriage.

The King showered the news with tears of gratitude, and returned urgent greetings, beseeching the Prince to come in the place of his messengers. Before a week had passed the palace was full of him. He came in high feather, and with a great retinue, eager to behold the unbeholdable that was to be his bride.

As for Innygreth, she kept her peace, and went her ways at leisure, carrying ropes and files and ladders and swords and chain-armour to her lover in prison, that by craft or courage he might make his way out and escape; and all this she did by the spell of invisibility which rested on her. ‘But first,’ said Sir Percyn, ‘I will stand my trial, and declare my innocence before my judges.’ And that, indeed, was the wreck of his chances; for when, after long waiting, he was tried secretly and condemned to death, he was placed at once in a narrow cell, where the windows were so narrow that no filing could make room for a man’s body to pass through, and the walls were too thick and the warders too many for there to be any other means of escape. But all this was afterwards.

Therefore, at the time of the Prince-suitor’s coming, Innygreth’s mind was at ease, and she had full confidence that her power should work her lover’s release; and as for marriage, she knew that in the end she was her own mistress.

So when the Prince stood before her, and fawned and bowed, she curtseyed to him with her candle and told him she liked him well. And the wooing prospered, being pushed on by the King, till a whisper got to the suitor that the Princess was not so discreet of blood as to make a safe wife if none could watch over her. At that his suit also faltered, and he talked of affairs of state requiring a postponement of the nuptials.

Then the King in despair told him what he had never told to man before, and by what hard condition alone his daughter could ever escape from her invisibility. Then the Prince-suitor, who had a fine presence and a light heart, laughed, and said, ‘It seems to me that if the Princess will but consent to like me well enough one day before our marriage, I may lead a fair bride to the altar in the eyes of all men.’

When King Agwisaunce took in the discreet ingenuity of the proposal, he became perfectly shocked with joy; and thought he, hugging his conscience into a corner, ‘Am I a father or a monster to devise this thing for my own daughter?’ Nevertheless, despair of other salvation so pricked him that he hurried on eagerly the preparations for the nuptials. For all the while terror blew on him in little hot gusts lest his daughter should forestall him and ruin all: since, were she now to appear visible to the world, the Prince-suitor would understand the cause and have plain grounds for breaking the matter off.

The old crone that watched over Innygreth said to her father: ‘Often the Princess is not in her chamber, and I know not whither she goes.’ But the King, when he heard that, knew and trembled. Therefore to make all sure, he caused every door to be locked on her, meaning to keep her within, a close prisoner, till the morning of her marriage.

And now Sir Percyn being tried and condemned, the hour for his beheading had been fixed; and by the King’s will, it was to be at midnight on the night before Innygreth’s marriage. As that day approached, whenever the King and the Prince-suitor met, the latter smiled, as it is said augurs do, but the King cast down his eyes.

And now, indeed, despair was eating up the heart of Innygreth, for she herself was behind locks, that try as she would she might not slip by, and she heard from the talk of her women how the night before her marriage was to be the night also of Sir Percyn’s doom.

Now the grief that the Princess had no man could see, though her face was bowed down under the foreshadow of her lover’s death. Her light she put away, for often the shuddering in her hands might not hold it; but her lips gave out no sound of her sorrow. Only her mother, coming to Innygreth’s chamber, heard the soft falling of tears upon the floor. ‘Ah, my child!’ cried the Queen, and for pity brought the King in, and showed him where a pool had formed itself from that pure sorrow; and she said bitterly, ‘Thou canst not behold our daughter’s face, yet thou canst behold her tears: see the river of that grief which is in her! Yea, I have heard her heart breaking which I cannot see! Presently, I think, she will fall dead into our presence, and I shall behold her beauty too late but to weep over it. Is that indeed the end promised for her by the fairy?’ But the King said, ‘That is not the end.’ Though even now he would not tell her how the end was to be. ‘This is but a passing shower,’ said he: ‘to-morrow she shall shine!’

Every day brought in the piles of presents for the bride, and every night the palace was a-blaze with lights; but the King was sore at heart over the heavy condition that lay between him and the achievement of his daughter’s happiness, and his thoughts grew full of tenderness. He came and felt for her head bowed all low with grief: ‘Wilt thou not trust a loving father,’ said he, fondling it, ‘that to have thee happy and sound before his eyes is all the desire of his heart? But thy fate makes the way hard. Only believe that whoever I shall send unto thee, bearing my signet-ring, comes for thy good; and to-morrow, if thou wilt obey me well, thou shalt be a fair wife in the eyes of all.’

Then, when the hour drew on into night, he took her hand and led her softly to her bed-chamber; and said he, ‘See, I will myself keep the key to thy chamber; and whatsoever cometh through to thee this night cometh of my love. And this I swear to thee by my royal word, that to-morrow, when I see thy face plain, then thou hast only to ask thy will, and it shall be my wedding gift to thee, were it the half of my kingdom.’

He said to her waiting-woman: ‘When the Princess has put off her attire, bring it all forth from the chamber, that she may not rise up again this night.’ For he feared yet that she might rise by stealth in the night and give the slip to her fortune.

Therefore, when presently the Princess had unrobed herself and put out the light of her presence, the waiting-woman brought forth all the attire she had worn that day, and left Innygreth in only her bed-linen, nor was any other garment left for her to put on.

So presently, when all the palace slept, the King gave his signet-ring to the Prince-suitor, and also the keys of every door, and bidding him God-speed, made haste and departed.

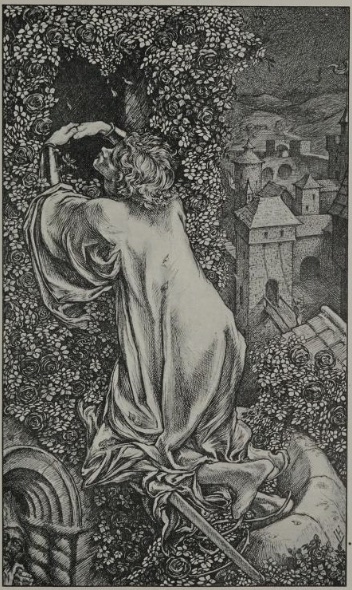

The Princess, left alone, rose up from her bed and found her garments flown. Yet had that hindrance been to her as to other maidens it had not kept her from her lover’s side, whose last hour on earth now drew near. Therefore, the door being fast, she opened her window and leaned forth, where so often before she had leaned with the touch of Sir Percyn’s face upon hers.

The deep warm summer night shed its breath upon her lips full of the scent of roses. So, remembering him about to die, she put forth her tender limbs and climbed down by the stems of the roses till her feet embraced the cool herbs below.

As she went, great thorns had made wounds in hands and feet, so that ruby drops fell from them and mingled with the large tears of dew that hung on the grass edges that she trod.

She passed by terrace and lawn and bower, till she came to the baser courts and quadrangles where the service of the castle was done. The draw-well was at rest after its day’s labour. In the two buckets, left standing for chance use during the night, water was wrinkling in the light of a grey moon. As she was crossing the open, a white hound came and lapped in one of the pails, drew out his head, and yawned with the water dripping off his jowl. Innygreth shivered, for he had not nosed her in passing, and she knew that this was the hound of death waiting till midnight should strike.

By the chapel’s west front she passed down more steps, and, crossing the garth, saw a lantern, and two men working under its beams. She stayed then, and saw how with pick and spade they had made room enough in the ground for a man to lie. The mould, as they threw it out fell over her bare feet. ‘The midnight brings rain!’ said one of the diggers, looking up. And Innygreth turned her about and went swiftly, having looked into a living man’s grave.

Then came she to the guard-house, passing between the two sentinels who stood there with crossed pikes. And at the door of her knight’s cell she halted, bidding herself have patience; for she knew that presently the jailor must come with the wine and the last loaf which Sir Percyn might eat ere he broke fast on the morrow in the fair house of God amid the company of His saints.

So she leaned her ear to the door, and heard calm breathing within. Then, even in her present distress, she had joy, thanking fate that had let her hold come fast on a heart so noble as this.

Presently came the jailor, carrying the spare meal that was to be Sir Percyn’s last; and he opened the door softly, and set it down by the bed, sighing to himself that so fair a youth was presently to die, for all that knew Sir Percyn loved him well.

Ye know well, how where he had let one in he locked in two. She, indeed, sat down on the bed watching Sir Percyn’s face; and, feeling the coldness of the prison walls striking into her, she took up her knight’s cloak to lay over her shoulders, and covered up her feet with the rest of his garments that he had taken off ere he lay down.

Presently she heard the blessing of her own name breathed through his sleep, and at that leaned down her face into the hollow of his palm where it lay upon the coverlet, and kissed it as one kisses the shrines of saints. In a while it closed softly upon her features, as a sensitive plant over the visiting bee whose honey it would take, and a waking voice said, ‘Is it Innygreth that is here?’

‘Even she, and sorrow!’ moaned the Princess, and laid her face against his.

‘O beloved,’ he said, ‘keep those dear eyes dry!’ For thick tears traced over him from under her lids, and even then a spot of blood from her hand showed upon his as he reached up to stroke her face. Then he started, clasping her. ‘How art thou wounded, beloved,’ he cried, ‘if this cometh from thee?’

She answered: ‘The roses, by which thou camest to me, I climbed down to thee.’ ‘Oh, blessed sad chance!’ he cried, embracing her; ‘for now mine eyes have seen the sweet colour of thy blood, shed out of dear veins for love of me!’ And as his arms clung round her in bitter sweet joy at that last meeting, he said, ‘Thou art cold, love, and trembling, for thy meek body is all but naked in this house of death where I am held captive!’ But she said, ‘What does cold or pain matter any more? Now I am by thy side it matters not; and when thou art gone, neither will it matter then. I have failed to win thy freedom or mine. I have failed in all but to dig thy grave in the chapel garth by the light of this grey moon!’ ‘But,’ said he, ‘though I had failed in all, having gained thee I should be happier in my end than all they who live, not knowing thy sweetness.’

Thus these lovers, each unto each, the saddest sweet things that hearts may make lips speak when parting comes to them. And the Princess took from him a lock of his hair, to have for ever on her heart when he was not there. And he said, ‘Beloved, hast thou it safe?’ ‘In my breast!’ said she; but he: ‘Now thou wearest it, it is gone from my sight.’

Then she said, musing sorrowfully, ‘Though I can come and go as I will, I have found no way for thee to escape; for this window is too narrow and these walls are too thick for thee to pass through, though by stealth I have brought thee file and rope, seeing that what I hold close to my own body shares my invisibility to the eyes of man.’

And even while she spake, there was heard below the tread of heavy feet, and the clatter and ring of steel arms; and by that the lovers knew that herewith came the guard to take Sir Percyn forth to the place of execution. Then, while yet the sound grew up the winding of the stairs, Innygreth compassed the full use that she might make of her charm: and before Sir Percyn knew what she would do, she had slipped into the bed and folded herself about him from head to foot. And with her lips to his face, winding her long hair over him: ‘Be quiet, thou dead man,’ spake she, ‘for now my body holds thine safe!’

And therewith those without, reaching the door, unlocked and threw it wide. And lo! a bed empty, and a cell void, as all eyes might plainly behold.

So straightway went out the cry that the prisoner was loose; and the guard, leaving the door wide, sped forth to search and stop all ways of exit from the castle.

Then Sir Percyn, lying hived in the warm breast of fair Innygreth, began to tremble at the very greatness of her mercy, and to be held so close in those dear arms. And spake he, twixt fear for his own frailty and worship for her divine charity, ‘Loose me, my heaven, and let us go, for the door stands open!’ ‘Nay,’ said she, ‘lie down, thou dear loon! For if we go forth together now, they will see thee, and thou wilt be taken. To-morrow the door will still be there, and we may get forth by some secret way, as I shall devise. But unless thou lie still, I cannot keep thee all hid, nor wrap thee safe from men’s eyes. O, my loon, my loon, I have taken thee up to me out of the grave; and this night I will hold my dead man safe!’

So in the morning, when the King, dreading whether the Princess had indeed escaped (for the Prince-suitor after long search had found her not), and hearing of the flight of Sir Percyn, came in great haste and dread to that cell:—he saw, indeed, that fair youth lying asleep and by his side a woman of most touching beauty, so sweet and pure and lovely an image of the Queen’s youth, that he doubted not it must be his own daughter whom he saw.

And as he gazed, in bitter wrath for all of which that sight gave token, the two sleepers stirred and opened glad eyes each to each. Wit ye well King Agwisaunce heard much sweet speech and worship pass between the pair, ere the Princess lifted her gaze to behold the King’s eyes fixed on her, full of fury. And first she trembled and fluttered at the sight of his wrath, and threw her arms protectingly over her lover to keep him hidden from the King’s eyes. But in a while, so new was the fixedness of his gaze, that she started up crying, ‘Oh, my Father, canst thou indeed see me with thine eyes?’

‘Yea, wanton, I do see thee!’ he answered; ‘A heavy sight it is. There thou liest with thy doomed paramour beside thee!’

Then Innygreth lifted herself smiling and said, ‘O Father, since now thou seest me, my will is that for a wedding gift thou do give me this very Sir Percyn to wed and live with in happiness and honour to my life’s end!’

Then the King remembered how he had given her his royal word; and as she had willed, so had it to be. Therefore is an end come to my story.

Now, had the King been as other men, and let the fairy’s will be in the first place, none of these sorrows had come about, nor need any have been wise concerning that thing, nor this have been written. Wherefore ye who like this tale be glad that the King erred not in faith to his wife; and ye that like it not, be grieved.

Word Count: 6644

Audiobook Format

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Laurence Housman. “Blind Love.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, pp. 64-81. Edited by Christina Peregoy. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 15 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/blind-love/.

Editors

Christina Peregoy

Rachael Buchanan

Jessica Monohan

Danny Daw

Taylor Topham

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

11 December 2017

Last modified

15 July 2025