Caught at Last

by Anonymous

London Society, vol. 10, issue 55 (1866)

Pages 80-96

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “Caught at Last” follows a young clergyman, Johnathan Williams, as he begins his first curacy. It is a domestic, character-driven, comedic story, told in the first person, that explores Johnathan’s shifting worldview as the values he has learned in his upbringing are tested. The story explores propriety, gender dynamics, and conflicting social values in Upper-Middle-class Victorian society.

Advisory note: This story includes an instance of antisemitism.

‘What’s in a name?’ asks the poet—‘a rose by any other name,’ &c.; and yet, there has been a difference of opinion on the subject.1From Wiliam Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Jonathan Bugg thought he should smell sweeter as Norfolk Howard; while as for myself—the humble writer of this story—I attribute the greatest misfortune of my life, by a roundabout way of reasoning, to being called ‘Johnny.’2Jonathan/Joshua Bugg was a famous example of a trend popular in the period of changing one’s name to sound more aristocratic in the hopes it would help social standing. After an announcement of his name change was published in The Times in 1862, he was mocked in other newspapers. (Jones, Richard. “Joshua Bugg Becomes Norfolk Howard.” Mr Joshua Bugg Changes His Name To Norfolk Howard, June 1862. Accessed February 28, 2025.) My name has always been ‘Johnny,’ and I think my nature, so to speak, gradually grew Johnnish; for didn’t every ‘Jack’ of my boyish days naturally hold a high hand over a Johnny? Petticoat government was the absolute monarchy by which I was governed. My father died before I could lisp; and my mother (with the best of intentions, doubtless), had old-established rules on the subject of education. Dr. Watts was her demigod; and though, in the primeval times in which that gentleman lived, when the rose was ‘the glory of April and May!’ he may have served as a sort of forcing-box for the young, yet now-a-days nature grows better by itself, even though the roses are delayed till June. ‘Train up a child in the way he should go,’ says the wisest of men.3Quote from Proverbs 22:6 in the Bible. Here again my mother thought she understood the wisest of men thoroughly; only unfortunately her idea of the way to be gone in was so narrow, that it was a moral impossibility for any one to walk in it. My early youth, therefore, was a series of deviations from, and draggings back into my mother’s ‘ way,’—she vigorously compressing her petticoats, lest in getting me back she should wander a step out of it herself. Birds’-nesting was not in this way—indeed it would be easier to say what was not in it than what was, it being a path of the barest. I only say this to show the system on which I was nourished, and by which I came through my college career (at St. Bees) in my mother’s eyes—triumphant.

I was ordained, and was going down to my first curacy in a small country village, where my mother thought I should encounter fewer of those snares she dreaded for me than in a town.

‘Good-bye, my dear boy!’ said she, with a tear in each eye. ‘I shall come and see you by-and-by. Heaven bless you!—and do see that the sheets are aired.’

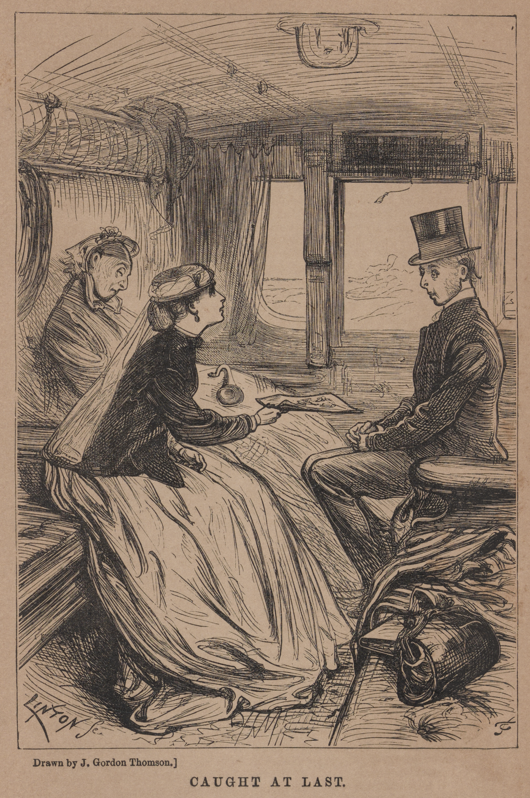

This was pleasant. My hat-box was inside the carriage, which contained both a young and old lady; my foot on the step.

My mother, in losing me, lost all consciousness of any one else the train might hold. I blushed to my hair, stumbled over my hat-box, and felt in the first stage of infancy as the train moved on with me to my first curacy.

It was not till some stations had been passed that I glanced up at my travelling companions.

I had a vague consciousness of the young lady suppressing a laugh as I entered, that was all.

Still I was a man, though shy and nervous; so I looked at the young one first. A pretty girl, with golden hair knotted up under a small round hat, that my mother would have condemned at once as unfeminine—and yet the small, rather pouting mouth, was very womanly. She looked alive for amusement, and dissatisfied with her materials.

Leaving myself out of the questions, the materials weren’t promising. Her companion was a tall, gaunt, bony woman, with a severe expression. Her eyes were closed, and on her knee there rested a speaking-trumpet. After looking, there seemed nothing more for me to do, and I turned my eyes upon the fields and trees we were passing. The young lady, however, was of the opinion that as Mahomet would not go to the mountain, as was natural the mountain could go to Mahomet.4A play on a popular idiom/proverb: “If the mountain will not come to Mohammed, Mohammed will go to the mountain.” It means when things aren’t coming easily you must take action and get them yourself (“If the Mountain Will Not Come to Muhammad, Then Muhammad Will Go to the Mountain Definition & Meaning.” Dictionary.com. Accessed March 8, 2025.)

‘Would you like to see “Punch”?’ she asked; and, though I doubted the propriety of the proceeding with our chaperon asleep, and thought the mice disposed to play too much, with the cat away, yet I could not but acknowledge there was nothing forward in either voice or manner.5Punch was a magazine “of humor and satire” that ran from 1841-2002. It was very influential in the birth of “cartoons” and published illustrations and writing that was witty and irreverent. (“Punch Magazine Cartoon Archive.” PUNCH Magazine Cartoon Archive. Accessed February 28, 2025.) ‘Punch’ was not a paper my mother patronized; my own sense of humour was not cultivated, and my taste slightly severe; therefore, having returned my thanks, I gazed somewhat gravely on a group of young ladies in striped petticoats, playing croquet, with more display of ankle than I thought decorous. The live young lady opposite me, taking note of the subject, began again—

‘Ah, the croquet picture! Isn’t it an institution?’

A hospital was an institution, so was a workhouse; but a game!—slang.

More ideas of the impropriety of the whole proceeding crossed my brain; as a clergyman, should I awake the sleeper by asking her if she felt a draught?

No; I was, though absurd, twenty-three still; so I merely said I did not play croquet.

‘Not play croquet!’ There was a world of meaning in the way the girl raised her eyebrows. I began a series of self-questioning as she reclined on the cushion and began to cut open the leaves of a yellow railway novel with her ticket. Ought I to play croquet? Did everybody play croquet?—even clergymen? The young lady asking the question could not be ignorant of my calling, my garb being eminently clerical. In spite of my convictions, I began to wish I could play croquet consistently; began to be sorry this girl had retired into the yellow novel, which, after all, might be worse for her than talking to me.

I even was meditating a remark, when a loud unmusical voice came from the far corner of the carriage. ‘Lizzie!’ it said.

Lizzie started, crossed over, took the trumpet, and called back, musically, ‘Yes, aunt.’

‘Are we near Marsden?’ Marsden! It was the name of my curacy!

‘Only a few miles off;’ and then Lizzie undutifully laid down the trumpet, and crossed back again.

‘She’s so awfully deaf,’ said the young lady.

‘What afflictions some are called on to bear!’ I observed.

‘That’s like Sunday,’ said Miss Lizzie, and then began to prepare for disembarkation. Crumbs were shaken out of her jacket, packages disinterred, with my grave and silent help (after the above irreverent remark), and a porter screamed out, ‘Marsden!’ I saw the ladies get into a yellow fly in waiting; I saw the keen grey eyes of the older woman fall on me as I stood patiently on the platform, till the fly was settled and despatched. Then I asked my way, and walked off to my lodgings. It was a dull little village of one street; but dullness in the way of duty was what I had expected. All the women at their doors and boys at play turned to inspect me; but I did not feel sufficiently at my ease to address a word to them.

My destination was a good-sized cottage, standing in a strip of garden, and a rather nice-looking old woman stood at the gate. She looked me over, as I came up, doubtless having an inward thanksgiving over my youth and innocence.

‘The last’s here yet, sir,’ she said, as we went in, ‘but he’s going tonight.’

‘The who?’ I inquired, anxiously.

‘The last curate, sir; we always has them, and we’ve had all sorts.’

Here she was obliged to pause, with the ‘last’ so near.

She opened a door and ushered me into a room which seemed to be luxuriously furnished.

My mother, though well-off, adhered to the torturous horsehair furniture of her mother, and ‘saved.’ Here were dark-seated velvet easy-chairs, a rich carpet, and divers little pretty articles that seemed to have been put in tastefully for a village landlady; but what offended the nose of my mother’s son was the smell of tobacco.

I was about hastily to remonstrate with my landlady, when I saw a man sitting half in and half out of the window—smoking; a man in a short, loose-fitting coat, who, as soon as he saw us, took the half of himself that was out of the apartment, and added it to the half that was in, and said—

‘ Mr. Williams, I believe, vice Parker, resigned.—I’m Parker. Mrs. Spinx, I will see you presently.’

That lady, in a state of unwillingness, left us, and left me in a state of mild astonishment. I had a great respect for ‘the cloth,’ and this ‘mixture’ shocked me.

‘When one puts off one’s shoes, one likes to see how they will fit another man,’ said Mr. Parker; ‘besides which, there is a trifle I wish to settle with you. Shall we do the business first, and smoke a pipe together afterwards?’’

(I told Mr. Parker, as I had told Miss Lizzis about the croquet—I never smoked.)

‘And yet you exist!—excuse me; well, then, I’ll smoke the two pipes afterwards. Mr. Williams, you observe this apartment?’

I assented (did he think I looked blind?)

‘Neat but not gaudy, eh?’ pursued the ‘last.’

I assented again.

‘Glad you like it. Well, this room belongs to Mrs. Spinx; but the furniture—at least one or two things—belongs to me.’

‘The rooms were said to be furnished in the letters my mother received,’ I gently remarked.

‘Probably. Mrs. Spinx said so, now, didn’t she?’

She did: would he, therefore, tell me which were Mrs. Spinx’s things and which were his?

Mr. Parker looked very doubtful; went to a coal-pan and a small deal table with plants on it, and said, ‘Mrs. Spinx; the one or two other things,’ he concluded, ‘are mine.’

‘But,’ I exclaimed, ‘a man could not live in a room with nothing but a deal table and a coal-pan; where could he sit?’

‘Very true,’ said Mr. Parker. ‘I believe, by-the-way, there was an article Mrs. Spinx called a chair when I came, but—’ (Mr. Parker shrugged his shoulders) ‘in the words of the poet, “it was harder than I could bear.” Accordingly I did not pack the furniture, supposing you would wish to take it.’

I looked at the easy-chairs, and sniffed just a little: it did seem hard that I should have Mr. Parker’s tobacco-infected room imputed to me.6The original text had a mistyped apostrophe at the end of this line.

‘Is it the baccy you don’t like?—a little camphor will soon take that out. You see, my good fellow, I’m off to-night to visit my lady-love, who disports on the moors at this time of the year, and I thought these chairs would be more in your way than in mine—they would be too much in mine! I’m no Jew; so suppose we say 30l., and have done with the subject.’

Of course I bought everything. And then while Mr. Parker smoked his two pipes, waiting for his train, he was in evidently good spirits and friendly towards me.

‘You’ll find this place beastly slow,’ he said.

It did not seem unlikely that what would be Mr. Parker’s poison would be my meat. He would not have survived life at my mother’s. The word ‘beastly’ itself was, to say the least, eminently unclerical, so the remark did not depress me. I therefore made an inquiry about my vicar.

‘The old humbug!’ burst out the last curate.

I felt my blood curdle—all my old early-trained reverence engendered by Dr. Watts revolted against Mr. Parker.

‘Hadn’t we better change the subject,’ I said, ‘seeing that I am his curate?’

The ex-one, with his legs hanging over one of the easy-chairs, as much at his ease as if it were still his, and the purchase-money were not in his waistcoat-pocket, glanced at me, amused.

‘The old man’s luckier than he deserves to be, anyhow,’ he said. ‘You’ll just suit him.’

I inquired if there were any well-to-do parishioners.

‘There’s Mrs. Bingham and her five lovely daughters (three of them are away just now)—she is piscatorially inclined.’

I felt horror-stricken. ‘Fishes!—a woman with a family!’

‘You see,’ pursued a little Mr. Parker, ‘you must not be shocked; she’s not rich, though she lives in a good house—her money dies with her.’

I felt relieved. ‘Well, it may be praiseworthy though masculine. Is there good trout in the stream here?’

Mr. Parker unexpectedly burst out laughing.

‘My dear Mr. Williams, excuse me, but you’re made for this place—positively made for it. Trout! No, very little; though to see Mrs. Bingham with her tackle all about her (a different fly for every fish) stand perseveringly day after day trying to catch one miserable sole—I mean trout—it gives one a feeling of positive respect.’

‘It must,’ I said warmly. I was glad to hear the ex-curate respected anything. I was afraid he didn’t. I really began to have a better opinion of him (though of course I could not approve his sentiments) as I shook hands with him on the platform that night.

The next morning as I sat looking over a pile of sermons I had constructed at intervals, my eye was caught by an object at my garden gate—an object of bulk and dignity—a clerical object, evidently the vicar.

How truly kind! my heart kindled. How I loathed the smell of that tobacco which surrounded me; how I blushed at the remembrance of the epithet which I had heard applied to this kindhearted man only the evening before.

The Rev. Dr. Walsh knocked like a bishop, and entered like an archbishop. He had (I say it now) a welling manner. He seemed to fill all the chairs at one, so to speak, and drive me into Mrs. Spinx’s coal-pan.

‘Mr. Williams!’ said my vicar, extending his hand.

The manner was benevolent—affectionate; it seemed to say, ‘Fill the chairs, my dear curate—I, your vicar, will retire into nothing.’

I took his hand, and felt my heart overflowing with love and duty. That eye, bright and intellectual—that broad brow—

‘Your first cure, I think?’ continued my vicar.

I assented.

‘Williams!’ pursued the great man—‘the name strikes me. I had a dear friend once of that name—he was a man who did his duty, and never shrank from work. Do you shrink from work?’

This was the man after my mother’s own heart—a man eager in the path of duty—eager to lead others therein.

I replied modestly, ‘I hoped I was wishful to do my duty.’

‘Ah! Yes,’ said my vicar, somewhat abstractedly. ‘My dear Mr. Williams, the fact is I am in affliction. I am not one who presses his grief on others (that I should look upon as selfishness), but in this case you can help me.’

I replied I should be too happy.

My vicar cleared his throat and went on.

‘Blessed as I am, and thankful as I am for my many blessings, yet in one thing I am unfortunate. I have a dear family, but the family suffers. My wife is delicate; our eldest girl, a sweet child aged fourteen, is fragile in the extreme. My lot is cast in the country, and my family requires a frequent supply of that ozone which is only to be found in sea air. My dear wife has with our children been at Scarborough for a fortnight. Gladly would I stay here alone unrepiningly (we should not repine, Mr. Williams!), but what can I do when I hear daily that my beloved child asks for “Papa?” “Her wishes must be gratified,” says our family doctor. I have been torn with doubts: is my duty here, or does it call me to my child?’

Mr vicar paused—and swelled!

From my position by the coal-pan I could see that agitation of my superior’s manner while alluding to his child, and flashing through my mind came the recollection of the man who had sat in the same chair only the evening before, and called him ‘humbug!’ I loathed the thought.

‘Oh! go to your child at once sir,’ I said (the dear little girl might be pining for him at this very moment). ‘I will endeavour, though unworthily, to fulfil your duties and—’

My vicar seemed to think I had said enough. He did not stay long after this, but he pressed my hand at parting, and said ‘God bless you, Williams!’

My feelings were mixed when the interview was over. I sat down again to my pile of sermons, but failed to derive my usual satisfaction from these interesting works. I had lost the benefit of this man’s teaching at the outset. I was very young, ardent, and enthusiastic, and—I was disappointed.

Sunday was the day but one after. On Saturday I had made the round of the village, shaking hands with mothers and kissing their offspring like a model young curate on the back of a penny tract. I could well understand a Parker considering the place slow. There were boys and pigs in abundance, a church in a state of dilapidation, and a modern vicarage near it with handsome iron gates. It was a commonplace village, devoid even of a permanent doctor, and yet overrun with children; but the state of the village has little to do with my story.

Sunday came. I rose early and nervous. My hands shook a little as I arranged my bands, looked twice to see that my sermon accompanied me, and did not recover from that Johnnyish feeling I was subject to till I stood in the reading-desk.

The congregation was small,—painfully small to a zealous young curate,—but just under the reading-desk was a pew containing three ladies. I could not help seeing them, or I should have preferred not to do so. One of them was not a stranger to me, she was my young fellow-traveller, the two other were tall, ordinary women. I caught a pair of blue—I mean my railway companion looked up, and if it had not been in church, would, I think, have smiled. The look seemed to say ‘Oh! it’s you again, is it?’ Then for the rest of the church service (and it gave me inward satisfaction) she kept her eyes to her book. Shall I say that it warmed me a little to my work to see that pew of ladies, as I ascended the pulpit steps?

My mother thought my sermons would get me a bishopric, and though not of that opinion myself, yet I still did think they had merits. This was my first sermon. My congregation was, without the occupants of the pew, limited to ten. I was in earnest, but—I was twenty-three. I felt an inward glow as I thought I might prove to the girl, who had laughed at me the other day, that I was not devoid of eloquence. Perhaps that eloquence might make an impression on this frivolous and worldly-minded young person. I had chosen one of my best themes—one to which I had affixed the ‘J.W.’ lovingly, and as I gave it out, it answered my expectations on delivery.

There was one passage, alluding to the snares and flowery seductions of this world, which made me feel all aglow against such seductions, as I denounced them. But did I raise any such kindred feelings in my congregation? I ventured to glance round. The ten hearers, from any expression in their faces, were evidently uncalculated to know the meaning of the word ‘seductions.’ I looked down into the pew; two tall, plainly-attired ladies sat listening intently, their eyes raised, their hands folded; but the one whom the words were intended specially to benefit, reclined in a corner of the large pew—fast asleep. Oh, ephemeral muslins and laces, and wearer as ephemeral!

I felt my indignation rise. The day, it was true, was hot, but why could she not listen as well as her companions? Were my words more suited to the comprehension of the latter? My mother would have hoped so. As for myself, I took off my gown with far fewer feelings of satisfaction than when I put it on.

Passing up the churchyard, the three ladies were in front of me, and I heard a voice from under a most delicate parasol say—

‘What a long sermon! I wish there weren’t sermons in summer, only ventilators.’

‘Hush, Lizzie,’ said one of the ladies, ‘and do recollect it’s Sunday.’

Again my spirit sank at what I thought the frivolity of this girl. My mother desired nothing more earnestly than to witness the bestowal of my affections, but then the object must be suitable. Suitable in her eyes, meant—quiet, easily led (by herself), retiring, a lover of needles and thread, rather than of millinery and self-decoration—whose views of pleasure should be of the teachers’ tea-meeting or ‘improving the mind’ order. From my shy nature, and early nurture on Dr. Watts, I, too, had the sort of idea that a pretty bonnet betokened a love of the word in the wearer, and a sparkling manner, an undue lightness of character; and yet, and yet—these were the ideas instilled into me. The time might be coming when views of my own should do combat with my mother’s views—which would be conqueror? At present there was no such conflict. I saw an elegantly-dressed young woman with worldly sentiments. I saw two plainly-attired ladies, who might each have been cut out to order (one was rather old to be sure) for a Mrs. Williams. Might it not be that the hand of providence had planted me here to choose a wife from these two? Time would show.

The afternoon service was equally as unsatisfactory as the morning one. There was the same small congregation, the same pew full, the same tendency on the part of Miss Lizzie to hurt my self-love, if nothing else, by falling asleep during the sermon, and afterwards my lonely meal and evening in my cottage.

A week had nearly passed away. I was beginning to get some knowledge of my parishioners, but—human nature is only human nature after all—I was also exceedingly dull.

My mother’s circle at home, though a restricted one, was a circle. It took in one or two young men who had never shown any disposition to forsake the ways of their fathers; it took in divers young ladies; they weren’t beautiful, or clever, or distinguished in any way, still they were young ladies, and twenty-three requires something of the kind.

Here was I, the sole moving orb in my own circle. I might gaze at and revolve round myself, or Mrs. Spinx, but I required more.

I had, two or three times during that week, fleeting visions of the ladies who sat below the reading-desk, but fleeting visions are unsubstantial. One morning towards the end of the week, as I was meditating getting a dog as a companion, there came a note which roused my pleasurable emotions, the purport being that Mrs. Bingham, of Beech Grove, would be glad if I would give her my company at dinner at five o’clock.

I must have been lonely, for I recollect I had a feeling of satisfaction that it was for this afternoon instead of to-morrow.

I was just finishing my toilet when a remembrance flashed into my mind. Bingham was the name of the lady who fished! I almost wished I weren’t going; but then was any credit to be placed on Mr. Parker’s statements?

After obtaining from Mrs. Spinx the route, I made my way to Beech Grove. A narrow land behind the church brought me to some white gates. Beech Grove did not belie its promising sound. There weren’t many beeches, certainly, but there was a nice neat lawn, and a few flowerbeds, and a verandah, and a carriage drive devoid of weeds. You might see Beech Grove in ninety-nine parishes out of every hundred, and live there comfortably. Cela dépend.7French for “it depends”

A man on arriving is at once on the scene of action. None of those mysterious paper boxes, out of which come we know not what to be put on at the house of entertainment, before wax lights and a mirror. (I believe if there are many ladies and but one mirror, this is a work of time.) A man benign not so easily put out of order in the transit, has not one minute for reflection for doorstep to presence chamber.

‘Mr. Williams!’ and then, following up my name, I was shaking hands with a long thin ditto, appertaining to my deaf traveling companion. Not masculine to look at, keen-eyed and severe, but correct to a degree.

‘My daughters,’ said Mrs. Bingham, ‘Jane and Elizabeth.’

Having a vague idea that Providence was in some way connected with my acquaintance with these ladies, I surveyed the Miss Binghams with interest. They weren’t attractive ( I mean to the eye). Jane was her mother over again, as the saying is, without the deafness, and with an acidity of manner that might perhaps have been due to her passed stage of youthfulness—and spinsterhood. Elizabeth was considerably younger, shorter, stouter, with curling hair, and more amiable expression.

True, her face was not distinguished by much beauty. Her nose was neither a delicate vivacious retroussé nor a statuesque Grecian; but why proceed?8An adjective meaning an upturned nose. Has the connotation of being attractive. Elizabeth was the sort of young person to whom I had been accustomed. Elizabeth had the outside characteristics of ‘suitable.’ If Providence had led me to the Miss Binghams, Elizabeth was the Miss Bingham, and the presence of Elizabeth made me more at home.

As the one man, I had to be entertained. Miss Bingham tried to draw me out on church architecture. Miss Bingham deplored the poverty of the parish in preventing the restoration of the church. Mrs. Bingham knitted, and threw in a word here and there, while Elizabeth bent over her work and was modestly silent.

‘Jane,’ said Mrs. Bingham, suddenly, ‘I hope nothing has happened to Lizzie.’

‘She is always late, mamma,’ responded Jane; ‘and knows, being a visitor, she will be waited for, which I call taking advantage.’

‘I am thankful she is no child of mine,’ said the deaf lady, heaving a sigh. ‘As it is, she is a great responsibility.’

Two minutes afterwards the door opened, and the ‘great responsibility’ came in—the young lady who fell asleep during my sermon—in a toilet that aimed at something above neatness, and that floated about her, a cloud of pink and white, something that might, like a jam tart to a sick child, be very good to look at and very bad for you. I had eyes and saw, but I was a man not to be led by my eyes—prudent beyond my years.

‘Lizzie, my dear,’ said Mrs. Bingham, ‘you’re very late.’

‘I’m sorry for that, aunt,’ replied Lizzie, at the top of her musical voice. ‘I met Charley Langton, looking so wretched, that I went farther than I intended, and he has come back with me in to dinner.’

‘Lizzie,’ said her aunt, ‘how—’

‘He has lost his father, poor boy, never got over it, and I thought—’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Mrs. Bingham, waving her hand, ‘no one is more glad to see him than I; but it’s the principle of young ladies inviting young men.’

Lizzie’s lips curled. ‘Young men!’ she said to her cousin, Miss Bingham, ‘why Charley’s only sixteen.’

‘You know mamma’s rules, Lizzie;’ and Lizzie turned away in a manner that made me jot down temper as another failing in this very faulty young person.

The entrance of Charley, a languid, delicate-looking boy, put an end to the discussion.

Mrs. Bingham certainly gave him as cordial a welcome as if she had asked him. Even the two miss Binghams greeted him with more demonstration than is usually bestowed on boys of sixteen. ‘Very kind,’ I thought, but it was a kindness Charley did not seem to appreciate, as he moved away to Lizzie in the window, and stood by her there in a languid yet easy way till we went in to dinner.

I found myself between Mrs. Bingham and her daughter Elizabeth, Miss Bingham took the foot of the table; their cousin and Charley were opposite me. Mrs. Bingham conversed a little with me about my mother and home, and loneliness here sympathetically; so that what with hot soup and the startling loudness of my replies, I became very warm indeed.

Elizabeth was — retiring. She wanted setting off on a subject; even then she did not go any extreme way, but replied modestly, and retired again. Miss Lizzie, too, was silent, and again offended my taste at the beginning of the meal. (I had many particular notions about young ladies.)

‘I am so hungry,’ she said; ‘riding round Drayton Hill, with all that delicious heather out, is beneficial to me. May I have some beer, Jane?’

‘You can have what you like,’ said Miss Bingham, acidly.

And Lizzie’s glass was filled. To drink beer seemed to me as masculine as a coquettish bonnet looked worldly.

I looked at Elizabeth’s glass. Pure water! and felt thankful.

The dinner was quite a plain one. After the soup, chickens and a shoulder of mutton. I trembled at the chickens, but Mrs. Bingham declining my aid, I was feeling able to converse with Elizabeth, when Miss Lizzie’s clear voice came out for the benefit of the table.

‘I’ve been offered two tickets today for the Beaconfield ball; it’s in a fortnight.’

Mrs. Bingham, busy with the chickens, did not hear. Miss Bingham exclaimed—

‘One doesn’t hear a sensible word there.’

‘Doesn’t one,’ said Lizzie; ‘well, I must be indifferent to sensible words, for I want to go very much. Do you recollect, Charley, the ball last year, and how you got spoony on Miss Brett, and quite deserted me?’

‘No, I don’t, Lizzie. I recollect being sent off by Percy.’

‘Hush,’ said Lizzie, laughingly, but I was busy with my thoughts.

Spoony!! A young lady to use such a word. I felt electrified. I turned to the gentle Elizabeth.

‘Do you, too, care for balls?’ I asked, somewhat anxiously.

‘No,’ said Elizabeth, in a very, low voice, and blushing; ‘at least,’ she added, ‘I always like the school treat more.’

Here was a disciplined mind for you. The carnal nature conquered— desire under control.

Said Miss Bingham, ‘You must regret the absence of your vicar, Mr. Williams.’

‘I do indeed; he seems such a superior man. He was divided between his wish to stay and help me, and his anxiety to be with his sick child.’

‘Did he leave you the key of his kitchen garden?’ said Lizzie, irrelevantly.

‘No,’ I replied, not seeing the force of the question.

‘He has such nice peaches,’ continued Lizzie. ‘When I was here last year the bishop came down, and the bishop had as many of them as he liked to eat, and Dr. Walsh was so pleased to see the bishop eat them. Has Mrs. Spinx any peaches in her garden?’

‘No, of course not;’ but I said I was independent of peaches.

‘Dr. Walsh says his have a peculiar flavour,’ said Charley. ‘Percy got a whole lot sent last year.’

‘Don’t you know the proverb, Charley, “Stroke me and I will stroke thee.” Dr. Walsh strokes Percy with the peculiar flavoured peaches; Percy must stroke the Doctor with a pine. Dr. Walsh, my dear, is partial to stroking, and does not object to an English pine.’

I felt aglow with indignation, though the young lady opposite seemed quite unconscious of such a feeling being possible.

Mrs. Bingham observed (it was wonderful sometimes how she heard), ‘It’s a pity his eldest girl is so delicate.’

‘Oh! Aunt Bingham,’ burst out Lizzie, ‘you know very well she isn’t. Dr. Walsh finds Marsden dull and Scarborough the reverse, and just because Emily hasn’t a colour—’

I could not wait to the end of the sentence—I could stand it no longer.

‘You seem to forget who you are speaking before, Miss D’Arcy. I am Dr. Walsh’s curate. Am I to sit and listen to slander against my vicar? There is always some one to impute evil motives to the best of men and deeds.’

Mrs. Bingham looked pleased. Charley began—

‘Mr. Williams, it’s not slander; it’s as well known—’

When Lizzie stopped him with a look, and then turned on me a straightforward glance out of her large blue eyes. She was certainly very pretty, especially with the flush on her cheeks they had now; but then, is not beauty deceitful?

She said nothing at first, to my surprise; but after her steady look the corners of her mouth curled with smiles, and she said demurely—

‘I still think Dr. Walsh ought to have left you the key of his kitchen-garden, Mr. Williams.’

Then she turned to Charley, and the two talked together for the rest of dinner, alone.

If beauty is deceitful, there was no deceit in Elizabeth; if placidity is estimable in a woman, Elizabeth was much to be esteemed. On principle I did like and esteem her; on principle, also, I disliked and thought little of her cousin. Our views on so many points coincided; indeed I might say on every point, about parish work, society, books, &c.

It was still daylight when dinner was over, and Lizzie said—

‘Oh! let us have a game at croquet. Mr. Williams, shall we teach you?’

It seemed a veiled attempt at reconciliation. I had reproved Miss Lizzie in a way many young ladies might have resented, so I gave in to the croquet.

Then Elizabeth said she had work to finish.

‘One of those everlasting flannel petticoats?’ suggested Charley.

(Another virtue—she made flannel petticoats!)

‘Charley, you’re a goose,’ said Lizzie. ‘It is just because they aren’t everlasting she makes them; but put them by for to-night, and be good-natured, Elizabeth.’

(Could she be anything else?)

So Elizabeth sacrificed the flannel petticoats at the shrine of croquet, and we had to choose our sides.

I have seen men linger over this, as if preference in croquet showed preference in life. Charley, however, showed no such hesitation.

‘Come Lizzie, I won’t desert you to-night,’ he said; so we began, and of course I was beaten. Elizabeth played in a tranquil manner, while her cousin’s ball was like a shooting star, and a shooting star had far the best of it.

‘Don’t you think this rather a poor game to be made so much fuss about?’ observed Elizabeth to me.

(She had tried three times at one hoop, and we stood side by side.)

‘I did not like the notion of it,’ I said, ‘but it seems harmless.’

‘Oh yes, or I should not play, of course.’

And then Lizzie made a swoop down, and sent me to a laurel bush at the antipodes.

I was not near my partner again till just the end of the game. Lizzie was advancing to the stick, and Elizabeth asked me—

‘Do you think her pretty?’ (How very feminine!)

Yes, I thought her very pretty but I did not think it was the kind of beauty I admired the most.

‘Oh! Mr. Williams,’ said Elizabeth, with more animation than I had seen her display, ‘you think exactly like I do. I call her pretty, only it’s a pity she’s such a flirt.’

I did not quite like this. I did not doubt Lizzie being a flirt, only the good-nature of Elizabeth in telling me so. Or was it that she had detected something inflammable about me, and so set up a fire-guard as a precaution. I would not believe that anything but good-nature could dwell in that Miss Bingham, whom I believed Providence had selected for me.

‘She has only an invalid father, and he spoils her so,’ continued Elizabeth. ‘I am very fond of her; but we are so very different—she likes balls and things—and I—’ Miss Elizabeth’s autobiography was closed by Lizzie coming up.

‘There! we’ve beaten you, Mr. Williams, so now there’s nothing left for you but to make the best of it by saying something polite.’

Was this flirting? It might be, yet somehow it seemed harmless, like the croquet. Then we went in, and had some tea and music. Elizabeth played, certainly not professionally, but nicely, and I did not like too much time devoted to music.

‘Now, Lizzie, sing something,’ said Charley.

‘Lizzie,’ called out her aunt, ‘remember your sore throat.’

Lizzie said it was quite well.

‘I’m responsible for you,’ said Mrs. Bingham.

So Lizzie, with very flushed cheeks, gave up her own opinion, and sat down with Charley to a game of chess, over which they talked a great deal. Then Elizabeth drew a low stool near her mother’s chair, and we made quite a little home picture, with Lizzie excluded—and yet—and yet—I wished (as Mrs. Bingham gave out her improving sentences, and Elizabeth sounded a gentle accompaniment) that if such a thing were possible, blue eyes, and pink muslin, and golden hair with pink ribbon in it weren’t of this world, worldly. I wished it very calmly, but the wish was there, even as I felt ‘safe’ with my mother’s views of safety, seated beside a girl in grey silk who was suited to me.

So the evening came to an end. Charley said he would go with me as far as the inn where his horse was, and we took leave together. We had just got to the end of the drive when pattering feet behind us made us turn round.

Ghosts are not in my category of beliefs, of course; yet I should as soon have expected to see one as Lizzie.

Charley exclaimed, ‘Why, Liz, what is it?’ as she stood panting, and I waited, supposing she had some girlish message to a friend.

I started when she began. ‘Mr. Williams, I wanted to tell you I was sorry for what I said at dinner. I should not have spoken what I thought so decidedly. You were quite right in telling me every one may be mistaken, and I respect you for it. Good-night.’

She held out her hand (what a little white hand it looked in the moonlight!) and giving me no time to speak, she ran back to the house.

I could not help thinking about this. Was not the proceeding unusual? not quite in accordance with the Williams’ rubric. That was true, but then—was the Williams’ rubric infallible? A young girl running out to tell a gentleman she was in the wrong! It might be impulsive, but it was honest and genuine. What a pity she was so fond of balls! What a pity she dressed herself in attractive webs to dazzle the eyes of foolish men! Was she a flirt? At all events she had not thought it worth her while to try me. Was I duly grateful? I could not doubt Elizabeth’s word. If the Williams’ estimate were right, she was all a shepherdess should be—while Lizzie was one who, with the crook in her hands, would lead the lambs all astray. I felt sure of this—almost sure—and yet, as I fell asleep, I did wish jam tart was not so unwholesome.

I did not see anything unwholesome for many days, though I often saw Elizabeth in the cottages, seated by the aged, like a ministering angel. Was it necessary that such angels should be clad in sober garments and the most unattractive of bonnets? I believed so.

I was sorry not to see Lizzie—sorry in a vague sort of way, when an old woman asked Elizabeth one day in my presence why Miss Lizzie never came now.

Elizabeth coloured, said she did not know, and soon after took her leave. So, there had been days when Lizzie, too, had been a ministering angel. I like to think of those blue eyes bent on the complaints of the poor—those small hands busied. Johnny Williams, your imagination is wandering. The fair worldling had tried and gone back, while Elizabeth was daily at her post.9Original text had a typo here, saying “wordling” instead of “worlding”. Daily, indeed; and so I could not fail to carry her books sometimes, or see her to the Beech Grove gates, or put up her umbrella for her if it rained, and thinking what a good wife she would make on the William’s principle. I tried to love her. The loving had not come yet, however, and I was surprised, and took my own heart to task about it. I was so taking my heart to task one afternoon when I met Charley Langton as I turned from the Beech Grove gates. I had declined entering, as somehow I felt as if Mrs. Bingham were beyond me. She was Elizabeth’s mother, of course, but perhaps I had not got over that undiscovered report about her fishing—at all events, I did not seek her presence. I met Charley on a fine young horse, but riding somewhat moodily. He pulled up at the sight of me.

‘Have you been in there?’ (meaning Beech Grove) he asked naturally, seeing me so near the gates.

I said ‘no,’ without thinking it necessary to allude to my téte-à-tete with Elizabeth, and then asked if he had been.10French term meaning a private conversation between two people.

‘No. I can stand as much as most fellows, but I can’t stand that woman often,’ and looking back, he shook his fist at the Beeches; ‘but perhaps you are an old friend,’ he added, smiling.

I did not feel called upon to defend Mrs. Bingham, at all events yet. She was not my vicar. I said I had never seen them till I came here.

‘Lizzie is kept in a complete state of imprisonment; it’s a horrid shame,’ Charley went on; ‘she got into such a row about the other night, so now she declares she won’t go into the village, for her aunt said she went to meet—people,’ added Charley, pulling himself and his horse up at the same moment. But could I doubt who ‘people’ were, simple as I was—no—no.

‘Why does she stay?’

‘Why,’ pursued Charley, ‘she has only an invalid father, and she don’t like bothering him about such a trifle.’

I gulped down the insult to myself of being ‘such a trifle.’

‘I should think Mrs. Bingham’s a clever woman, only rather masculine, isn’t she?’ (Here was a neat way of getting to the truth of the ‘fishing.’) I had misgivings as to the lawfulness thereof, but then she might be my—not a pleasant word.

‘She don’t smoke or hunt, if you mean that by “masculine,”’ said Charley; ‘perhaps if she did it would improve her.’

This was shocking, but I was ‘hot’ now.

‘Doesn’t she fish?’ I inquired.

Charley looked slightly astonished. ‘How! fish?’

‘For the support of her family?’

‘Oh yes—fishes for her daughters—Elizabeth’s often the bait—regularly poked down too.’

What a light broke in on me! about my future—too. So, it was slang on the ex-curate’s part, and Johnny Williams hadn’t seen it. I felt the awakening dreadful. The subject was not a pleasant one, and I could only say, ‘Oh, I see,’ and change it. Perhaps Charley had not noticed my inferior sagacity to his own. I hoped not, for he began—

‘A whole lot of the 6th Dragoon fellows want me to get Lizzie out. Captain Grey saw her last year. She is awfully pretty, and a regular brick too. Oh, and I say,’ continued Charley, ‘my cousin Percy has some people the day after to-morrow, and he told me to look out for some men—will you go? He’s an awfully jolly fellow.’11The original text had the apostrophe marking the quotation in the wrong place, after “Oh” instead of “say.”

I had misgivings that ‘awfully jolly fellows’ and I were not suited. However, the world seemed just to have been turned upside down, and I felt a little extra shake on one side would be trifling.

‘I don’t care much for society—gay society I mean.’

‘Oh,’ said the boy, a smile curling his lips, ‘it’s all right then—just the sort of place for you.’

And here, after saying I would go, we parted. Parted—to think. Could it be that Elizabeth was in the secret of her mother’s plans? No, oh no! Could it be that Elizabeth had not known why her cousin had given up the village? My thoughts turned to Lizzie. If it had not been from the force of Dr. Watts and my mother combined, those deep, trustful blue eyes, and that frank lively manner would have attracted me very much; as it was—

I was going to the party.

* * * *

Just what would suit me! The ‘jolly fellows’ then turned over continental views with an anxious eye on the young lady near them. Having finished looking at them, they tried to remember a riddle, which they rarely could, and they made a rush at the light refreshments, which ended the evening, to relieve the monotony of nothing to say by asking if somebody would have a sandwich. It was half-past eight o’clock when the cross between gig and dogcart brought me to the jolly fellow’s abode. Then I found that Mr. Langton had been born with a silver spoon in his mouth. I saw it in the pretty, though not extensive park we drove through; in the blaze of light which dazzled me when I found myself, with some misgivings, in a handsome hall. There was a sound of laughter through a door on my right, which did not remind me of anything I had ever heard over ‘continental views.’ It was with no misgiving, but with a certainty that Charley had taken me in, that I entered a room on the left—a room which had been despoiled of all furniture and carpeting, and had only ominous candles and mirrors, clad in flowers, on its walls—a room that was not suited to a Williams. At the other end there were folding doors open, and a tableau of ladies beyond—not a single man. As I followed the servant across the floor (slippery as ice), I wished vainly it were ice, and that I could sink under it before we reached that other inner room. I had been punctual, and this was the result.

A large room with corners and recesses, and ladies everywhere! I was in it, hot, cold, agonized!—the only man. And then, oh, relief! a snowy vision came and stood before me. What matter that the pearls on the white neck and the flowers in the golden hair betokened preparation for the slippery foundation of the next room? The hand stretched out to me, the sweet voice speaking to me were Lizzie’s—she had come to befriend me.

‘You are the only person who thinks punctuality a virtue, Mr. Williams,’ she said, blushing, for she had come across the room to speak to me, and perhaps Mrs Bingham haunted her. ‘Mr. Langton has some of the gentlemen to dinner, so we must try to amuse you for a little while. Shall I introduce you to Miss Blake, Mr. Langton’s aunt?’

She crossed the room with me—she guaranteed me, so to speak, and made me no longer a stranger. She told Miss Blake (an old lady with white hair and a face which had essence of kindness in it) who I was, and a stranger here, and Miss Blake grew ‘double distilled’ essence at once.

‘Shall I introduce you to any one I know?’ asked Lizzie; and I thanked her and said, ‘By-and-by.’

Might there not be a time when a man wanted tempting with jam-tart, having been on plain diet very long? It was very nice having that pleasant voice saying ‘Mr. Williams’ (my name had never sounded musical before). And then, all too soon, there was a sound of opening doors, and some men came in. One crossed over in the easiest, most careless way (I felt it was so different to my way) to where we were. Not the sort of man I had ever seen carrying about sandwiches in my mother’s circle,—it was the ‘jolly fellow.’ He had light whiskers and moustache, and rather languid blue eyes. The languor vanished as he shook hands with, and welcomed me.

‘Have you been fighting over that election, Mr. Langton?’ asked Lizzie.

‘Yes, and I’ve won, of course. Just fancy yourself in the olden time, Miss D’Arcy, there’s been a (consult Bulwer for correct names)—and being victorious, I come up to get the prize from you.’

‘It was usual in the old time to see the results oneself, before giving the prize,’ laughed Lizzie.

‘Exactly so, mademoiselle; but then, you see, we are in the new times now, not the old ones, so you will dance the first with me.’

‘Really! are you equal to it? A quadrille, I suppose!’

‘No—as I go in for exertion at all, it may as well be a waltz. Please accompany me to the fiddler.’

I heard her lower her voice and say something about ‘old ladies,’ and then the answer, also low, of which I only caught the words ‘old women’ and ‘hanged.’

She shook her head, laughing again, and then put her hand on his arm, and he led her away. It seemed to me as if the little white-gloved hand rested confidingly there.

‘A flirt!’ Was it for the dislike to think her such, and the condemnation in which I held such things, that I watched her so narrowly? There were many other men now, and girls fair, dark, pretty, and yet I did not trouble my head about their morals. I only saw one couple, and how—after the young host had led Lizzie to the band—he whirled her round the room with the blue eyes looking over his shoulder. How I condemned dancing! I would preach against it next Sunday, for Lizzie’s benefit, if she would not fall asleep—only I believed she would. And just then I turned, and found myself being spoken to by the old maid.

‘You don’t dance the waltz, Mr. Williams. Ah! we must have a quadrille presently. Do you know any of these young ladies? There’s one of the Miss Binghams looking at those prints by the recess—shall I introduce you?’

And then for the first time I saw Miss Elizabeth. She was not joining in the giddy dance, though she was arrayed in costume that looked like it. Her arms were bare; they were also red; and at the moment when I first saw her, her face looked cross below a green wreath.

I said to the old lady I knew Miss Bingham, and went up accordingly to the table by the recess.

‘I did not see you before, Miss Elizabeth.’

‘And I did not expect to see you,’ was the reply.

‘I was deceived as to the nature of the party.’

‘Many people are deceived,’ said Miss Elizabeth, somewhat tartly. (Did this mean Elizabeth was deceived in me?)

I was silent. The young lady looked ‘put out.’ Had she heen an ordinary girl, I should have set it down to the fact of her being left out in the dance; but then Elizabeth was not an ordinary girl—or I had tried to think not—and I supposed she did not dance.

She seemed to think better of her crossness, and gathering her garments together, said—

‘Won’t you look at these views, Mr. Williams? They are very good.’

I sat down beside her, and together we surveyed cities, and steep mountains, and decorated cathedrals. Was I not at home now? Was not this the sort of thing to which I was accustomed? And yet, and yet—the heart is deceitful above all things. As I sat by the side of Elizabeth, and turned over the views, I felt as if I should like to throw my scruples to the winds, and be in the position of Mr. Percy Langton.

‘I should like to go to Cologne to see the cathedral; should not you?’ said the young lady.

I answered abstractedly; her words fell flat. I wondered what she had in mind when she put on her green dress and wreath. Surely a plainer costume would have done to turn over views in. And then the music stopped, and we saw the dancers sauntering about the other room. I felt my téte-à-tete growing irksome, and was glad when Charley, looking mischievous, came up and broke it, with a tall lanky man in tow.

‘Didn’t I say this was the right sort of thing, Mr. Williams? Ah! Miss Elizabeth! may I introduce Captain Crossfell for the galope?’12The original text was missing an apostrophe after “gallope?”

Elizabeth blushed violently; she hesitated; she glanced at me, and then she stammered, ‘I don’t dance round dances.’

‘I beg your pardon, Miss Elizabeth,’ said Charley, ‘but as you always used to dance round dances, I was not aware of the change. Captain Crossfell, I will soon find you some one who dances everything.’

The tug went its way, and again I was left with Elizabeth. Could I mistake the way in which she looked at me when refusing to dance? I hoped I could mistake it, because I felt to-night, as I sat by her side, it was not a position I should voluntarily choose. Lizzie came up to us next, on Mr. Langton’s arm—came and stood by her cousin.

‘Elizabeth, you haven’t been dancing; I will introduce you to some one for this.’

Again Elizabeth’s cheek flushed. ‘I don’t dance the round dances.’

Lizzie for one moment looked astonished, and then I saw the same disdainful curl on her lips I had noticed there before, as she merely said, ‘Oh!’

A tall, dark, fashionable-looking man here made his way to us.

‘Miss D’Arcy,’ he said, ‘I’ve timed myself exactly, and this is ours.’

I thought Mr. Langton eyed the speaker with rather less than his usual nonchalance, as he bent down to Lizzie and led her away.13The original text had a misplaced apostrophe at the beginning of this line.

Even I, Johnny Williams, eyed him with small satisfaction. There was admiration of his pretty partner in his dark eyes. Mr. Langton stood near me through the dance; but he wasn’t clerical, nor did I feel so. I forgot all the bread-and-milky notions on which I had been nourished. My eyes followed Lizzie’s movements and the dark man’s. Why did they dance so little? Anything was better than the way he had of talking to her.

‘Mr. Williams,’ said the host, suddenly, ‘you will dance this quadrille.’

Dance! I! And then, before I had replied, Lizzie was near us again, with very bright eyes, and cheeks, and her golden hair floating over her shoulders.

I felt like St. Anthony. I would burst the trammels. Elizabeth was looking up. She danced quadrilles—well, let her.

‘Will you dance this with me, Miss Lizzie?’

She opened her bright eyes very wide. ‘Oh, yes; with pleasure.’

It seemed to me that there was a barometer near me, which sank to ‘stormy’ in a moment.

Could I believe, as we took our places, that my feet were on that slippery floor?—that I had beside me a blue wreath and a gossamer dress?—that instead of instructing Miss Lizzie in the way she should go, here was she teaching me the figures?

Had it come to figures?

We had a vis-à-vis, of course; that vis-à-vis was Elizabeth and a youth, nondescript as to age, and looked upon by the young ladies as some one who might be snubbed with impunity.14An escort or counterpart. Elizabeth had not so snubbed him; but her expression was not favourable to any attempts at conversation on the part of that youth. Silently she advanced; silently gave her cousin her hand; and if ever lady’s eyes said ‘Traitor!’ Miss Elizabeth Bingham’s eyes said it to me, when she got near enough in the ladies’ chain. I cared little (though it might be ungrateful) for such talk. There were other speaking eyes near me, and a sweet voice too. If only she would change a little!—and yet, what did I wish to see changed? The delicate dress which added to her beauty? The winning manner which made men love her? No. Round dances: and I would speak to her about these same round dances.

There was little time to speak in the figures; but, alas! they came to an end; and with her hand still on my arm, I did not much care. I could promenade with her more conscientiously.

‘Have you ever seen the conservatory, Mr. Williams? and should you like?’

Like! I felt as if I should not object to living there, as we strolled through the rooms (with that dark man envying me—I felt he was) and got among the ferns and flowers—Miss Lizzie and I. Now was my time. I had read of sermons in stones; this should be in a conservatory.

‘Your friend, Charley,’ I began, ‘took me in about this party; he did not give me to understand it was to be a dance.’

Lizzie laughed.

‘And you were startled by the absence of carpet. Well, isn’t this far nicer than what you expected? We talk far less gossip; and it makes one feel happy, going round to that delicious band.’

I could not help confessing to myself that it was nicer than I expected; but I must not shrink from my subject.

‘Going round!’ she had said it; here was an opportunity.

‘I do not see why people should not be as happy going square as going round,’ I said. I wanted to put it as gently and pleasantly as possible. Miss Lizzie, who was smelling a rose, continued doing so. I must speak more plainly. I wasn’t understood. Miss Lizzie’s face emerged from the petals.

‘And I don’t see why people mayn’t be as happy going round as going square: there’s no law against it, is there, Mr. Williams?’

‘There is no law against it, Miss D’Arcy,’ I replied; ‘but it seems to me that consistently—’

She stopped me. ‘Do you speak to me as a clergyman, or as a friend?’

I hesitated. Dare I?—No; I dared not. ‘As a friend,’ I said.

She drew herself up out of her rose.

‘Then, Mr. Williams, let me tell you I think you presume in lecturing me; because I have been taught to believe that I may enjoy the—the roses,’ she said, touching the flower; ‘and you think it better to shut your eyes and not look at them. Shall you take me to task for differing from you? No, no; and now,’ she added, ‘we won’t be cross with each other, but we won’t speak of this any more, shall we, Mr. Williams?’ She laughed a little. ‘You’d better speak to my cousin Elizabeth.’

Just at this moment, who should appear but that young lady, brought to the conservatory by that youth. I could feel for Mr. Langton hanging old women. Williams though I was, I could have executed that youth complacently. If they hadn’t come, who knows what might not have happened? As we passed out of the conservatory I caught the expression on Elizabeth’s face—it was not pleasing, but what cared I for that? As soon as we entered the dancing-room again the tall man with black whiskers, whom I regarded in the light of my bitterest enemy, came up to us.

‘This is ours, I believe,’ he said; and at these words the little white fingers slid off my arm, the band struck up, and once again she was floating around in one of those objectionable waltzes. That they were objectionable I still held—but, alas! I fear my moral scruples did not preponderate just then. That jolly fellow Percy Langton loomed up to me in anything but a state of jollity it appeared to me; indeed, so much on my own level, that, after Lizzie’s dress had just brushed our legs, I remarked, ‘Who is that man?’

‘Which man?’ said the host, looking at me somewhat curiously. I indicated him carelessly (just as if I had not been narrowly watching him the whole time).

‘Lord Ernest Wilmot.’

I shrank—at least I felt I did. My rival, a nobleman! He loved her—of course he did—he might be telling her so at this moment. The thought was maddening. There wasn’t a chance for me to speak to her then—others claimed her—others who probably loved her too! I hated every man there. I ordered my vehicle and was driven back to my lodgings. I loved her—I had loved her from the first. I would ask her to be my wife, and if she said ‘Yes’ (I gasped), why she might—dance quadrilles! How about the shepherdess and the crook? How about the jam tart and the sick child now? Pshaw! was I to pluck a dandelion with a rose so near? My mother’s views! —pshaw! again. My mother was an old woman, and had always looked through the narrow end of the telescope. I would look through the other side. I loved her. Would the party be broken up yet—and how about Lord Ernest Wilmot? Many a girl had the good sense to prefer manly worth (this was typified by me, J.W.) to—(here I grew vague). But now, how was I to do it? My intentions being strictly honourable, must I write to her father?—(man unknown, to man unknown—that would not do; besides, it would take too long). I would go over to Mrs. Bingham’s to-morrow morning and ask for the hand of her niece. My mind felt relieved, and I slept a little.

I rose looking very like a lover on the back of a yellow novel, and the appearance was not becoming. My tongue was dry, my hands hot; however, a clean, well-starched tie somewhat set me off. I tried to eat, and then I started for the Beeches. I heard my heart beat as my feet crunched the gravel of the drive. I lingered, and shut the gate carefully (it was always kept open), and then, being in sight of the windows, I could linger no longer. I was a well-known visitor, and the maid who came to the door said the young ladies weren’t down yet. I did not want the young ladies—I wanted Mrs. Bingham. (What a falsehood! I did want one of the young ladies, and I certainly did not want Mrs. Bingham.) I followed the maid into the drawingroom, and there Mrs. Bingham sat. I should have said she had a scowl on her face, only that I was about to ask for what (if given) would make even her scowls seem smiles to me. Then, for the first time, it struck me, how should I make her hear, for in the ardour of my love I had forgotten this. Making an offer through a trumpet would be very trying; besides, where was the trumpet this morning? We shook hands mutely. Then I drew a chair close and prepared for a shout.

‘Mrs. Bingham, I’ve come on an important mission.’

‘Missionaries?’ said Mrs. Bingham.

I must be louder—I must say something that could not be mistaken for ‘missionaries.’ I began again.

‘Mrs. Bingham,—perhaps you mayn’t have noticed that I—’

The lady didn’t, couldn’t, wouldn’t hear.

‘Speak louder, Mr. Williams. I do not hear you very well this morning.’

Very well! Why she did not hear me at all; and as to speaking louder!—But there was no help for it.

‘Mrs. Bingham,’ I began the third time, ‘I’m in love.’

The lady showed symptoms of hearing. She pricked up her ears, as all women will at the sound of ‘love,’ and a grim smile dawned on her face. (Surely she did not think I was going to propose to her!) She waited for me to go on, which I was hardly prepared to do. I should think never before had a man declared his love in such a vociferous manner. I almost wished I had gone to Lizzie straight,—but would not such a course have been contrary to intentions strictly honourable? This was more like driving the nail in, on the head. I had made plunge No. I now; plunge No. 2 would be less startling.

‘I want your help,’ I shouted. Mrs. Bingham heard again. Surely, Cupid being blind, has some electric sympathy with the deaf. The gods befriended me.

‘I know now,’ I continued, ‘that from my first meeting with Miss Lizzie I have loved her. Will you intercede for me? Do you think there is any hope?’

Mrs. Bingham rose from her chair erect.

‘I have noticed your attachment,’ she said, smiling grimly, ‘and I think there is. Wait.’

‘Dear Mrs. Bingham!’—I pressed her hand—a hand that was cold and hard to pressure—and she left me.

Gone to intercede. How I had wronged this kindhearted woman, and there was hope. It was doubtless (after the first) pleasant even to shout to Mrs. Bingham about my Lizzie, but to talk to the rose herself—how rapturous! How should I receive her? With the ground all prepared by Mrs. Bingham, would a kiss be too much? I trembled. I got up and looked in the mirror—a mirror that made my nose on one side and my eyes fishy. Was this my expression? I sat down and chirped to the canary bird: it was Elizabeth’s canary. Never mind—anything to pass the time. Then I heard footsteps. Could a heart come out? If so, mine would. ‘Be still, oh heart!’ says somebody—I said it. They had reached the door—the handle turned, and there entered Mrs. Bingham and her daughter Elizabeth. How unnecessary! But the mother spoke.

‘I told you, Mr. Williams, I thought you might hope. I was not wrong. My child Elizabeth (don’t blush, my dear) confesses that she, too, has loved you from the first. Marriages, they say, are made in heaven— may it bless yours!’

She fixed me with her eyes, and left us together.

Oh misery! —helplessness! I collapsed. I looked at Elizabeth. I felt I hated her. She stood by the fire looking evidently expectant. Expectant of what? Oh, miserable man! There seemed a timidity on the part of Mahomet about approaching the mountain—therefore—

‘Dear Mr. Williams,’ said the mountain, ‘don’t you feel well?’

‘No, ill—wretchedly ill.’

‘Can’t I do anything for you?’

By other lips what sweet words; but by hers—torture!

‘No thank you—not anything.’

‘Mamma has told me,’ continued Elizabeth, seeing Mahomet was still timid, ‘how you liked me the first day you came to dinner—don’t you remember?’

I groaned.

‘I am afraid you are suffering—the party last night—’ she stopped (was it supposed the champagne had disagreed with me?)

‘I think I had better go,’ I said, goaded to desperation.

‘Better!’ (reproachfully.) ‘Why better? Let us nurse you—that is if you love me. Don’t you love me?’

How would any one else have answered?

‘Oh yes—yes!’ I replied despairingly.

Her face brightened.

‘And yet you will go?’

‘I won’t inflict my misery on you.’

‘Misery! Oh, John!’

‘I shall see you again soon,’ I said, preparing to leave the room.

‘But your hat,’ said Elizabeth, seeing it lying neglected behind.

‘Hat!—what hat?’

She handed it—I put it on and banged in the top, Elizabeth evidently thinking I was on the way to a brain fever. She came to the hall door with me, and surveyed the landscape o’er. I don’t know what she saw—to me there were ashes on the flower-beds, and the trees wore sackcloth. She came down the drive with me.

‘Good-bye, dear John,’ she said; ‘you have made me so happy.’ She held up her pale face, and I had to do it. My lips felt like Dead Sea apples—I don’t know if she thought so; I dare say not. Of course I loved her, or else why had I just made her an offer. She could not come out with me on the road, thank Heaven! she had no bonnet on, so she stood by the gate watching me. I felt it, but I never looked back.

I did not see Lizzie again, she left (or was sent home?) the next day, when I was lying ill and helpless. Then the Binghams invaded my lodgings (taking advantage of my weakness), which helped to retard my recovery. When I once began to get better, with daily increasing strength came renewed hope—but it was too late. One cold wintry day I heard of Lizzie’s approaching marriage with that jolly fellow Percy Langton; and if, after this, there was any struggle against my fate, it was a struggle without energy. My mother came down to me, and came out strong, but Mrs. Bingham came out stronger by succumbing to her, and I was like a figure, pulled by strings, at these good ladies’ will. Elizabeth was meek and submissive to my mother. She wore dingy garments, and adored Dr. Watts; she maintained her position during the Creed, and could make a rice pudding. If I did not love her, I ought to do so, or there must be something very wrong with me. Indeed, there was something wrong with me—I was bitter, disgusted, dissatisfied, and in that frame of mind I was brought to the altar.

An Englishman’s home is his castle. Quick, take up the drawbridge, and let no spy enter into mine.

Draw your own conclusions from what I have told you, but don’t expect any key to such conclusions from me—I durst not give it you. Only, they say marriages are made—somewhere! Mine was not!

Word Count: 14398

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Rachel Brown

Clark Bailey

Vince Daurio

Em Moline

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

10 March 2025

Last modified

25 October 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | From Wiliam Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jonathan/Joshua Bugg was a famous example of a trend popular in the period of changing one’s name to sound more aristocratic in the hopes it would help social standing. After an announcement of his name change was published in The Times in 1862, he was mocked in other newspapers. (Jones, Richard. “Joshua Bugg Becomes Norfolk Howard.” Mr Joshua Bugg Changes His Name To Norfolk Howard, June 1862. Accessed February 28, 2025.) |

| ↑3 | Quote from Proverbs 22:6 in the Bible. |

| ↑4 | A play on a popular idiom/proverb: “If the mountain will not come to Mohammed, Mohammed will go to the mountain.” It means when things aren’t coming easily you must take action and get them yourself (“If the Mountain Will Not Come to Muhammad, Then Muhammad Will Go to the Mountain Definition & Meaning.” Dictionary.com. Accessed March 8, 2025.) |

| ↑5 | Punch was a magazine “of humor and satire” that ran from 1841-2002. It was very influential in the birth of “cartoons” and published illustrations and writing that was witty and irreverent. (“Punch Magazine Cartoon Archive.” PUNCH Magazine Cartoon Archive. Accessed February 28, 2025.) |

| ↑6 | The original text had a mistyped apostrophe at the end of this line. |

| ↑7 | French for “it depends” |

| ↑8 | An adjective meaning an upturned nose. Has the connotation of being attractive. |

| ↑9 | Original text had a typo here, saying “wordling” instead of “worlding”. |

| ↑10 | French term meaning a private conversation between two people. |

| ↑11 | The original text had the apostrophe marking the quotation in the wrong place, after “Oh” instead of “say.” |

| ↑12 | The original text was missing an apostrophe after “gallope?” |

| ↑13 | The original text had a misplaced apostrophe at the beginning of this line. |

| ↑14 | An escort or counterpart. |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.