Gurdom’s Ghost; A Shore Shooting Adventure

Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches; a Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British and Foreign Sport, vol. 1 (1885)

Pages 233-238

Introductory Note: Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches provides stories of sport and adventure that focus on such topics as hunting, camping, and horseback riding during the Victorian era. Wilf Pocklington wrote many first-person narratives for this journal. “Gurdom’s Ghost” is an adventurous tale about the narrator and his friend, Gurdom, hunting along the shore of Lincolnshire. The narrator recounts the story as a local legend. Illustrated by R. M. Alexander.

A FEW years ago there was probably no more attractive ground to the shore shooter than the immense saltings that line the estuary of the Wash, on the Lincolnshire coast. Stretching away for miles, and in many places giving at low water a breadth of two miles of mud, or mud and sand, intersected by creeks, ditches, and drains, tenanted only by the wild fowl, and the few men who went in quest of them, a more desirable place for shore shooting cannot well be imagined.

About the best place along the coast was a village called Frieston Shore. I call it by courtesy a village; but it was then simply a dozen or so farm-houses scattered loosely around two large hotels, which, to a stranger, seemed a most incongruous alliance. These hotels depended upon the trade arising from the vessels of large draught, that, being bound for the port of Boston, some seven miles away, were unable to enter the somewhat shallow river, and consequently discharged their cargoes by means of lighters from the deep-sea moorings know as ‘Clay Hole.’

In the famous duck winter of 1870 I received a letter from an old friend of mine named Gurdom, asking me to make definite arrangements for a long-deferred wild-fowling excursion, and a week from the receipt of his letter found us both comfortably settled at ‘Plummer’s Hotel,’ at the ‘Shore.’

Gurdom was a perfect stranger to these parts, but I, having been born almost on the very borders of that part of the Wash, had known every creek and ditch from boyhood.

Our host provided us with a capital dinner, and during the evening we loaded a supply of cartridges; afterwards we had a chat in the bar of the hotel with some of the fishermen, and the one professional fowler of the district.

As soon as it was light next morning we were moving, had breakfast, filled our flasks and sandwich tins, and started down the rude roadway that led us a mile or so into the desert of mud.

We were both carrying 12-bore guns, weighing about eight pounds and a half, both barrels full choke.

At the time I write, the useful 10-bore introduced by ‘Wildfowler’ was still in embryo, and, of course, for shore shooting in heavy mud, this is the bore to carry.

Arriving at the end of the road we began business in earnest, and, slipping into our mud pattens, we made our way towards the water’s edge with that peculiarly graceful, undulating motion common to the shore shooter in pattens.

A bleak north-easter was blowing straight in from the German Ocean, keen enough to cut a pole in two, and it came across those dreary flat saltings with an added keenness. The same weather had prevailed for the previous week or two, and, as usual under the circumstances, the birds were somewhat easier to approach. We held a consultation, and agreed to work up the coast towards Leake, I taking the higher shore, and Gurdom the lower one, thus giving him an off-chance at any birds I missed. The old retriever and I worked every creek systematically, and some very fair sport was obtained.

Towards noon I shot a large curlew that Gurdom flushed out of a very deep creek, and I declared my intention of sticking him up as a decoy, and waiting in the creek for results. Gurdom declined, saying it was too cold to wait about, whistling the retriever to follow him. He made his way along the coast towards Leake.

I hunted about for some drift-wood, and, cutting two suitable skewers, soon had my curlew fixed, beak in the mud, apparently very busy. I then retired to the creek, which was deep enough for me to stand upright in, and waited.

Not long, however.

Before a quarter of an hour passed there was the once-heard-never-to-be-forgotten ‘skreek’ of a curlew, and one came flying over the creek to cry ‘halves’ with my decoy. Bang! and down he came, almost at my feet.

I kept perfectly still for some little time longer, and then the sound of wings reached me. I peeped cautiously between the two hillocks of mud I had made on the edge of the creek, and my heart nearly came into my mouth, for there were four ducks and three mallards inspecting my curlew from a distance of about fifteen feet.

I have never had ‘buck ague,’ a disease common to our transatlantic sportsmen, but it could not be worse than the feeling I experienced for the space of half a minute. Then it passed, and I was all right.

One old duck was eyeing the curlew in a very suspicious manner, and I could almost imagine she was turning up the tip of her bill and saying contemptuously:—

‘Well! I never saw a curlew on crutches before! Don’t believe it is a curlew at all!’

To these sentiments a general ‘quack’ and preening of feathers seemed to reply:—

‘Quite right! guess it’s a fraud. Let’s go.’

However, I cut the picnic short at this juncture, and just as their heads were all wisely wagging together I pulled, and two lay dead; a third, hard hit, went floundering down towards the water; the other four rose. I just caught the leader under the wing as he turned in his flight, and brought him down with that ‘thud’ that has such a charm to a sportsman’s ear.

I climbed out to gather up my spoil, but having no dog, my wounded bird was in a fair way of getting off without further damage.

‘Confound it! Where’s Gurdom and Nell?’ I muttered. I could not see them anywhere, and concluded he had worked up the saltings to the ‘Shore.’

It was now about 3.30 p.m., and the inner man was making a piteous outcry, so I gathered up my bag and turned my face homewards, well satisfied with my share of the day’s sport.

As I reached the bank I passed the coastguard.

‘Just off in time, sir,’ said he: ‘this north-easter is bringing the tides in full thirty minutes early, this last day or two!’ And turning round, I saw that the tide was well over half the saltings, with a depth of about three feet already at the place where my decoy had stood.

Have you seen my friend pass in?’ I queried.

‘Well, no, sir, I can’t say as I have; I saw him down opposite the Toft Sand about two hours ago, and I have not seen him since.’ After a few more words we parted, and I entered the hotel.

Gurdom had not come in.

Nothing in that fact to give me any uneasiness, perhaps my readers will say, but to any one knowing that coast as I did there was every cause. The two-mile trail over those flats is a good hour, or hour and a quarter’s work; and if, having good sport, he had driven it to the last minute before starting, the fact of the unwonted early tide, and the dangerously swift sweep with which it covers those flats, almost at one unbroken roll, rushing up the deep ditches and creeks like a rapid, and spreading simultaneously on every side, made it a question almost of life or death.

I ran out on to the high bank and swept the saltings with a glass, but no figure was in sight.

It was now nearly dusk, and knowing how bewildering a strange shore is, I had a lantern hoisted up on the flagstaff of the hotel, and away I ran towards the coastguard station, nearly a mile down the coast. I reached there nearly breathless, and in a few words explained matters. The men wanted but a few seconds to throw oars into the boat, light a lantern, and run the boat down into the water. Then three of the coastguards and myself jumped in, and bent to the sternest race I ever rowed.

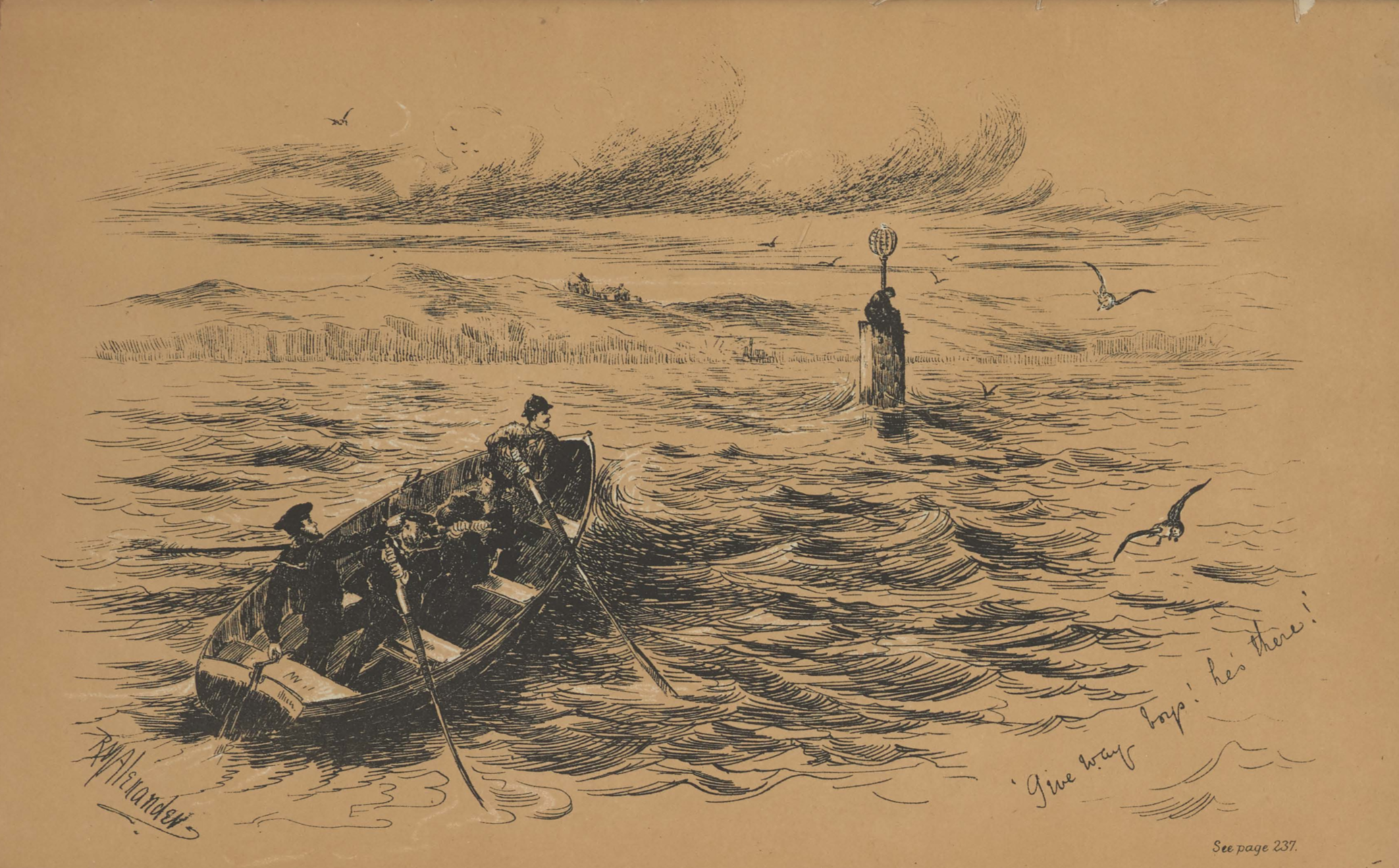

‘Reckon we’d better make for the line of beacons, sir,’ said the leader of our party; ‘it’s our only chance, if he’s in the water.’

The wind was colder than ever, and as the spray from the lipping waves flew over us now and again it froze on our clothes and hair. Away sped the boat, almost flying through the water, and in a very short time, which seemed hours to me, we reached the first beacon, which was merely a long stout pole with a basket on the top, placed at intervals along the coast to show the position of the sand-banks.

‘We had better work up the coast, sir: there is the Shore Beacon, which will be the most likely spot.’

Away went the boat in the direction of the ‘Shore Beacon.’ This differed from the others in having been built for a lantern, instead of a basket, and was a solid oak post, four feet square and twelve or fourteen feet high, with a pole and basket at the top, and rude steps still remaining in its side, by means of which the men had climbed to light the lantern in the old days.

Suddenly the man at the tiller called out, ‘Give way, boys! he’s there! I can see him on the beacon!’ We gave way with a will, and a few strokes ran us alongside.

There was Gurdom at the top, insensible, crouched all of a heap.

I climbed quickly up to him, and found him as I feared, nearly dead. He had climbed up, and, becoming numb, had placed his arms around the pole, and tied his wrists together with his handkerchief, to which circumstance he undoubtedly owed his life. I cut the handkerchief, and we lowered him into the boat. Then three of us rowed for the bank, and the other, stripping Gurdom to the skin, dashed salt water over him and rubbed his arms and body as hard as he could.

Arriving at the bank, the inmates of the hotel were all waiting to assist, if necessary. So, wrapping him in a blanket, we carried him into the hotel to find a hot bath and everything ready. It was evidently not the first case of the kind they had had.

Slowly and painfully life returned, and some two hours afterwards we laid him in bed, and he was soon fast asleep; and when he awoke next morning there was little the matter with him.

‘A trifle stiff, old man! nothing more; but, by Jove! that was a near go. You thought me insensible when you found me, but I saw and heard you as in a dream, and only became totally unconscious after reaching the hotel. Where’s Nell? The faithful old beggar stood it as long as she could, but was at last driven back, half wading, half swimming, by the incoming tide.’

I hastened to assure him that Nell had turned up at the hotel later on, and was just at present very busy downstairs with a great pile of bones.

As may be expected, the coastguard men had no reason to regret the exertions they had made on his behalf, and he is well remembered among them, as I understand every Christmas a little genuine Scotch whiskey finds its way to the station. But this is strictly entre nous.1French for “between us.”

The old beacon is still standing, and instead of ‘The Shore Beacon,’ is generally known as ‘Gurdom’s Ghost.’ Such is fame!

It stands on the salting between the Toft Sand and the shore, and is the only beacon for miles that can be mounted. If any of my readers visit the neighbourhood, any fisherman will point it out.

The following morning his gun was brought in, and we finished the week with a splendid total. But tempora mutantur.2Latin for the changes that the passage of time brings. Of late years the number of birds here has decreased beyond belief, what with the erection of docks lower down, and the new laws making the fisherman riddle their fish in deep water, the wild fowl appear to have sought a more secluded and better feeding-ground, and the winter before last I tramped over these saltings for six hours, and never emptied a single barrel.

Word Count: 2164

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Wilf Pocklington. “Gurdom’s Ghost; A Shore Shooting Adventure.” Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches; a Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British and Foreign Sport, vol. 1, 1885, pp. 233-8. Edited by Marcus Cain. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 5 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/gurdoms-ghost/.

Editors

Marcus Cain

Daniel Sowards

Emily Bush

Cosenza Hendrickson

Posted

21 March 2020

Last modified

5 July 2025