Her First Deal

Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches; a Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British and Foreign Sport, vol. 3 (1886)

Pages 89-97

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: This witty and engaging story by Cuthbert Bradley delves into the complicated world of horse-dealing through the eyes of Lucy, a young woman determined to handle her first business transaction—something a Victorian Lady should traditionally not be doing. The quasi-romance piece is targeted towards a more feminine audience despite being in a journal geared towards sporting audiences—typically men. Playing with the societal expectations of the time, the piece captures the comedic clash between Lucy and her proper and lady-like mother as well as Charley Martingale, the potential horse-buyer with ulterior motives.

‘OH! what do you think, mamma? I’ve had an offer this morning!’ exclaimed a smart young lady, in a tailor-made dress, as, seated at the end of the table (that is to say, if there be an end to an oval) she was picking the merry-thought of a chicken for her lunch.

‘My dear Lucy!’ said the middle-aged lady so addressed, in a tone of remonstrance, and holding up her hand to restrain her impulsive daughter, for the servants had not yet left the room.

‘Oh, I’ve been on the look-out for a good offer for some time!’ continued Miss Lucy.

‘Ahem! Peters, will you give me some dry sherry?’

‘And this morning I think I’ve had a good one from Charley Martingale!’ continued the young lady, who, being intent on her lunch, had not noticed the impression her conversation was making. The well-trained butler actually tottered for a moment as he handed the dry sherry; and the young footman, who was new to the situation, looked sheepish all the rest of the lunch-time.

‘Peters, will you order the landau for two o’clock? Lucy, shall you drive with me this afternoon?’ said mamma, rather stiffly, trying to check her daughter.

‘Well, no, mamma dear; if you’ll excuse me this afternoon. You see, Charley is a bit shifty, and I want to book him at once: it’s too good a chance to let slip.’

‘At least, Lucy, I would have you remember, that in all matters of importance it is advisable to consult your seniors first.’

‘Oh yes, mummy dear; I consulted old Wire, the vet, this morning, and he thinks I couldn’t do better!’

‘I think, Lucy, we will postpone the subject until after lunch!’ said mamma, severely.1Original text lacks a period at the end of the sentence. Likely a typo.

The two ladies, it is quite evident, were talking of totally different subjects–asking cross-questions and getting crooked answers. Lucy was a handsome, well-developed girl of nineteen, with plenty of style, a good figure, and possessed of an abundant flow of spirits, which made her welcome everywhere. She confessed to being mad on one subject, and that was the horses; and was, of course, talking of horses now: in fact, she was perpetually talking about them; not to poor dear mamma, though, because she usually acted as a wet-blanket on the subject.

The young lady was much excited at the prospect of her first deal in horse-flesh. It had become known that she wanted to sell her old chestnut horse, Naughty-boy; and Charley Martingale had, for reasons which will appear later on, made her an offer for him. Lucy had no sisters, but four brothers, to whom she was more than usually endeared for she took a lively interest in all they did, and they were as smart young fellows as one might wish to meet. Dick, the eldest, was in the Guards, and the others were variously occupied. They often talked to her about ‘chopping’ and ‘changing’ horses at enormous profits; and she saw no reason why she should not do the same. And the plucky young lady determined to transact her horse business herself, her brothers being away; for mamma, very wisely, would not have them hanging about at home in a quiet neighborhood, with nothing to do but to get into mischief and keep her on thorns.

Poor, dear mamma, since the Colonel’s death suffered from a weak heart, and devoted her attention mainly to a rare collection of bric-à-brac and objects of virtu.2French phrase meaning: a collection of miscellaneous or decorative objects, often with little value. She may have heard Lucy express a wish on a previous occasion to sell Naughty-boy, but it had made little or no impression; for what cared she about horses so long as they looked sleek and didn’t shy?

So we find at the conclusion of lunch, and after the servants had withdrawn, poor, neutral-tinted mamma begin her quiet reproof:—

‘My dear Lucy! what did you mean just now talking in that absurdly frivolous manner? I didn’t know what you were going to say next!’

‘Oh, it’s really too absurd!’ said the young lady, shaking with laughter, as the mistake dawned upon her. ‘Did you really think that I was talking of myself? No! I was talking about horse-dealing. There now, dear mamma, aren’t you shocked?’

‘I wish you would be more reasonable,’ said mamma, reproachfully; for she disliked anything approaching a practical joke. ‘You think a great deal too much about horses, Lucy!’

‘Oh, perhaps, some day I shall take to needlework—like you, dear mamma!’

‘What I mean, Lucy, is, that your taste for horses is likely to take you into the society of not very desirable people. I hope, for instance, that you won’t get too intimate with young Martingale, for he is not quite the companion for you.’

‘Oh but, mummy, he is so young and unsophisticated, and I can manage him. And he’s rather amusing because he is so absurd.’

‘He often oversteps the bounds of good taste, and I am afraid he is not a very steady young man, either.’

‘If he’ll buy my horse I’ll forgive him all that,’ said Lucy, sotto voce.3Italian phrase meaning: in a low voice, so as not to be overheard.

‘The manner in which he behaved the other day at dear Miss Pincher’s was too disgraceful!’

‘Why! does Charley visit there? I never knew it before.’

‘He was calling with his sisters, and they were discussing M. Pasteur’s cure for hydrophobia.4Literally the fear of water, though during the time it often instead referred to rabies. Fear of water was a common symptom of rabies, and was discussed frequently during the Victorian period as an awareness and fascination with diseases grew. (John K. Walton, “Mad Dogs and Englishmen: The Conflict Over Rabies in Late Victorian England,” Journal of Social History, vol. 13, no. 2, 1979: pp. 219-39. JSTOR.)

You know the Martingale girls are members of an ambulance class?’

‘Oh, yes! They doctored Charley’s hand last Christmas when his terrier bit him; and a pretty life he led them.’

‘Well, he was telling Miss Pincher about the bite; and the poor soul, in her nervous, apprehensive way, cross-questioned Charley as to whether he felt any ill effects, and whether he had taken the necessary precautions, when he almost frightened her out of her wits by beginning to bark like a terrier.’

‘Oh, he can imitate a terrier splendidly!’

‘She insisted that he must be mad, and rang the bell violently to summon the servants: the fright quite knocked her up for the rest of the week.’

‘It’s just like Charley! Just the sort of thing he would do!’

‘Now, Lucy, I must go and get ready for my drive; and remember my wishes with respect to Charley Martingale if you see him this afternoon.’

Chapter II.

Charley Martingale was a very important man—in his own estimation. He was twenty, good-looking, and had a well-shaped leg for breeches and boots. He had often turned over in his mind the possibility of being able to strike up a friendship with Lucy, simply, as he persuaded himself, with the view to a flirtation: at present, he only knew her distantly; and as Lucy was very commanding in presence, and Charley very young, it was a difficult matter to know how to approach such a goddess, and one who appeared to be idolised by so many men: for she had crowds of admirers, although she did not seem to recognise them in that light—they were simply her brothers’ friends, and therefore hers.

But why, it may be asked, did not Charley get his sisters to help him? Alas! he was anything but a model-brother. He was always ‘at his sisters,’ so to speak, and teasing them with such questions as, ‘Why didn’t they get married like other girls did?’ He presumed that, as the eldest son, he would be the heir, and he determined to set his face against the possibility of having to support maiden sisters. And further, he was ‘mad on terriers,’ and was always getting something for these wretched animals to worry. His sisters’ kittens disappeared directly they reached a fightable age; and when Charley was taxed with having spirited them away he pooh-poohed the matter, and talked of keepers, poaching, and game.

No! Once, when Charley, in a weak moment, asked his sister Bell to plead his cause with Lucy, or, as he put it, ‘make the running for him;’ she answered, ‘Help you to know Lucy? No, my dear boy! she’s a great deal too nice for you!’

But at last Charley saw his way without assistance from any one; for, having heard that Lucy wanted to part with her horse, Naughty-boy, with whose performances he was acquainted, he wrote a polite note, asking if such were the case, and if forty pounds would buy him.

Lucy, in her enthusiasm at the prospect of a deal, construed this into an offer, but wrote back by return:—

‘I want 50l. for my chestnut horse, Naughty-boy. He stands 16-1, is rising 10 up to 13 stone, has a bald face, and white off-side heel. He has carried me three seasons, and can jump anything. If I send him to Tat’s I shall put that reserve upon him.

‘P.S.—Give my love, please, to your sisters.’

(Charley didn’t; he kept it all for himself.)

He then wrote for the minutest details of the horse, not that he really cared about it, but merely because it necessitated her writing another letter to him, and gave him the opportunity of another back again to her. Each of his letters, though, became less business-like; and ‘Yours, truly’ crept on to ‘Yours, very sincerely.’

I don’t want to show up Charley Martingale, but between you and me, dear reader, his letters were rather misleading. It is all very well for a youth to write about ‘my groom,’ and ‘I want a horse for this and that.’ Of course, you cannot but imagine that he has a huge establishment of his own to back up his assertions. Anyhow, his devices, whether justifiable or not, resulted in that which he chiefly desired—an appointment with his inamorata.5Italian word meaning: in love, or lover.

Charley set to work to curl his hair and decorate himself from top to toe; his boots were like looking-glasses; and such a huge pair of spurs, too! To dress preparatory to going horse-dealing with a petticoat requires much consideration. After a ride of some eight or ten miles—the hotel-keepers who let horses for hire preferred to call it the latter—Charley reached ‘The Limes.’

‘Was Miss Lucy at home?’ ‘Oh, yes! and disengaged.’

Charley strutted about, and clanked his spurs, and antic’d with his gloves and whip, and pantomimed with his hands; in fact, did ‘all he knew’ to appear to be ‘all there!’

‘How are you?’ said Lucy, as she at last appeared on the scene. ‘It’s very good of you to take the trouble to come over to see my old horse.’

‘I’m sure that any little trouble on that score is more than rewarded by seeing you, Miss Lucy!’

‘Ah, ah!’ said Lucy, making a delightful courtesy. ‘Can I offer you afternoon tea? I know men usually vote it slow poison.’

‘If you made it, it would be quite the reverse!’ (‘Deuced neat!’ thought Charley.)

‘Well, really, if you are so sugary, I shall not put any into your tea,’ replied Lucy, laughing.

‘From your hands it is not dependent on sugar for sweetness.’

‘I am sure you do not talk such nonsense when you have tea with Miss Pincher; and I know men don’t really care about it: so you shall have a cigarette and a glass of sherry after business.’

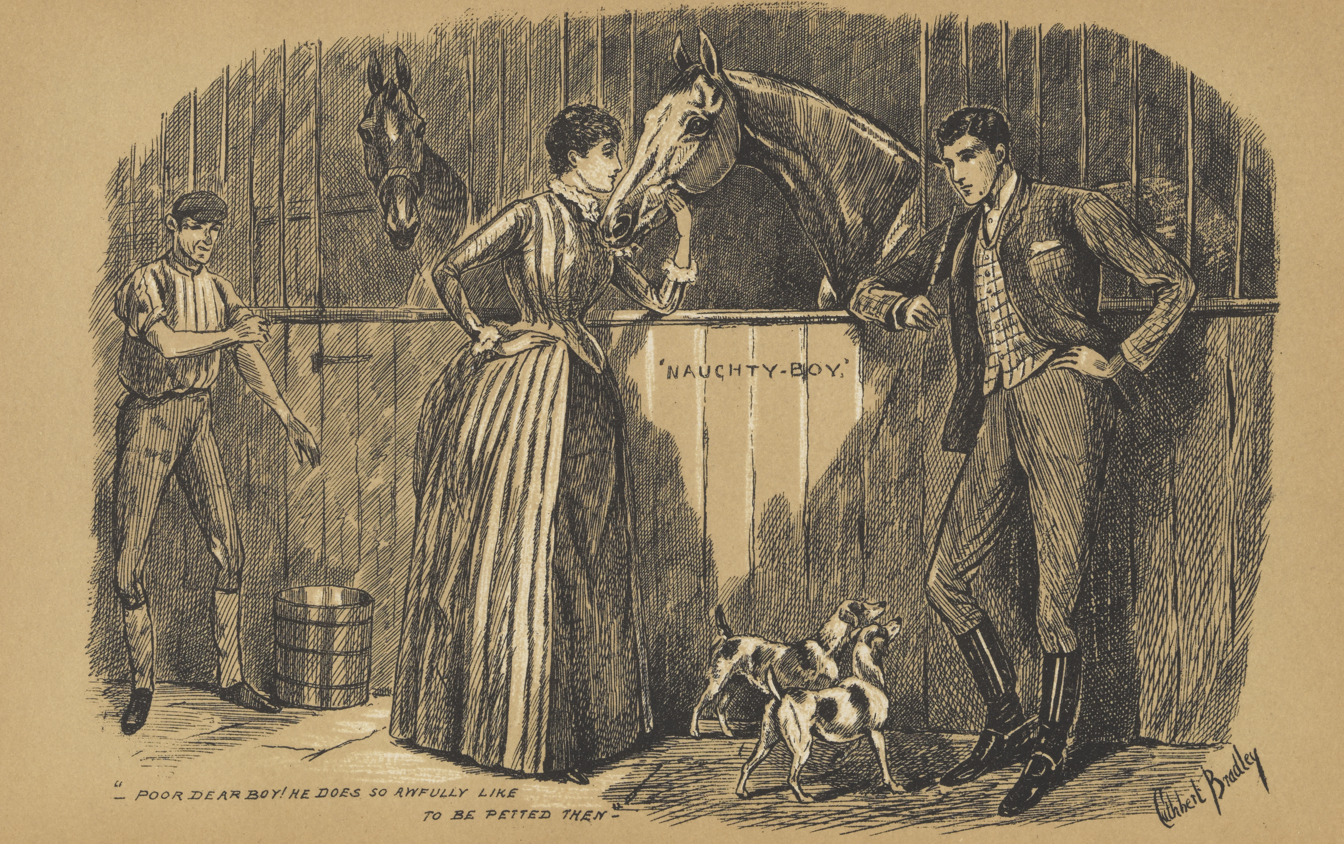

Lucy meant business, too; and, without further parley, led the way to the stable. Charley was not quite so keen on business; he would have preferred afternoon tea, for a tête-à-tête with Lucy was what he wanted.6French phrase meaning: literally, a head-to-head, but often referring to a private or intimate conversation between two people. He felt that she had found him out, headed, and stopped him: so easily, too, that if he didn’t mind, she would as easily make him buy her horse, whether he liked him or not. Naughty-boy stood with his head over the half-door of the box, and neighed a recognition as Lucy entered the stable. As she stroked his tan muzzle he nibbled the flowers she was wearing. ‘Poor dear boy! he does so awfully like to be petted then!’ said Lucy, caressing him. Somebody else stood by and looked horribly jealous of the old horse.

The groom appeared from the harness-room and entered the loose-box, with the usual ‘Cuck, cuck; cum up, ‘oss!’

Naughty-boy snorted and shifted restlessly, back went his ears, and the off-side white heel was hitched up an inch or two from the ground, as Withers slid off the clothing that Charley might see him stripped.

‘Make the horse show himself, Withers; he’s all tucked up,’ said Lucy, standing in the doorway, lamenting that Naughty-boy should put on such a fiendish expression at the sight of a stranger in his box.7Original piece has missing end quote mark after ‘tucked up.’

Charley nibbled a straw to the regulation length, and tilted his hat on to his nose, as he ran his eye over the lengthy chestnut to see what he could find faulty with him.

‘Been fired for curbs, groom—eh?’

‘Yes, Sir! on both hocks; but he’s sound on ‘em.’

‘Handle him! He has a very useful set of legs,’ said Lucy.

‘Yes, he has,’ said Charley, who didn’t half relish having to go so near that off-side white heel: ‘but I don’t like the way his head is set on.’

‘Oh, he has a better expression when he has a bridle on!’ said Lucy. ‘You shall see him out now that you have handled him in his box. Withers, put the saddle on him; we’ll try him round the paddock! Now you shall have your cigarette!’ and she led the way back to the house. Lucy had heard of champagne lunches at sales, and the fancy prices a moderate outlay in wines sometimes produces, and in the innocence of her heart she attached much importance to the effect the sherry and cigarette would produce on the supposed intending purchaser. It certainly did produce an effect. Never was a youth more enthusiastic about tailor-made dresses for ladies (she was wearing one, of course), and he wanted to discuss the various ways in which ladies do their hair; he wasn’t in the least little bit ‘horsey.’ When at last the young footman interrupted the tête-à-tête by announcing that Naughty-boy had been cooling his heels at the door for the last ten minutes, she thought he uttered something very like d——.8 Likely a curse word omitted from the original manuscript.

‘I feel sure that you will like him when you see him going,’ said Lucy. ‘And I’d sooner sell him to some one—like you—I know,’ she continued, leading the way to the door and her purchaser back to the subject.

‘I am sure you pay me a compliment, Miss Lucy; the old horse is a lucky animal to belong to you. I know some one who wouldn’t mind being in his place.’

‘Oh, thank you, I am sure! But I hope that he will be just as fortunate when he belongs to you, for he’s a dear horse!’

‘Yes, that’s what I stick at! It is a tall figure you want for him—horses are cheap just now; as cheap as they ever were!’

‘Come, Mr. Martingale, that’s very unkind of you; you’re not afraid of the horse, I am sure—he’s honest!’

‘Oh, certainly, Miss Lucy! I do like the horse, and yet there is something, I don’t know what! you know.’

‘I know, though, Mr. Martingale! it’s not the horse that you are afraid of, it’s me!’ said Lucy, whose keen perception saw through our hero. ‘You don’t like horse-dealing with a lady?’

Charley felt that he was fairly run to ground, and nothing but a miracle would keep him from buying the horse, if he wished to save himself from being detected as a gay deceiver. ‘Well, Miss Lucy, that’s rough on me, but I’ll tell you what I will do; if he can gallop and jump, I’ll bid you fifty.’

‘Or, rather, you must give me fifty,’ said Lucy, laughing, as Withers helped her into the saddle.

Naughty-boy stepped along gaily with his young mistress in the saddle, and she showed off his paces to advantage round the paddock. Charley stood there watching him, or rather, his eyes were riveted on the graceful outline of Lucy’s well-proportioned figure, as it moved to the motion of the horse. What a pair they made! Old Withers was also watching his young mistress and Naughty-boy. ‘Bless em!’ he exclaimed; ‘there’s a pair of thoroughbreds for yer! there’s no sham about them! they’ve both got their names in stud-books, she and the ‘oss!’

Lucy now roused the old horse up and sent him at a smart pace two or three times round the paddock, popping him over some gorsed hurdles. To wind up, she galloped along the centre of the paddock for a stiffish-made jump, that had been used for schooling a hunter over. She sent him at it at a rattling pace, when the old horse, who was a bit blown, blundered at the jump and came down a regular crumpler. An old horse falls heavily, and lies like a tree, and Naughty-boy was pretty well knocked out of time. Lucy, fortunately, was flung clean out of the saddle, and when Charley ran to her assistance she was lying insensible from a slight concussion in the fall and faintness from the sudden shock. What was he to do? Withers was off his head with fright, so Charley saw he must act for himself. He therefore despatched Withers for the doctor, and decided to pick her up and carry her to the house.

Oh! of course, you men readers wish you had been in his place; that is to say, if you never have been so situated. But it is not as easy as it looks to pick up a well-grown girl; and it was the first time Charley had tried to carry a lady, and he had no idea that they weighed so much. We can hardly say Charley found his task a light one, and could not prevent her head from hanging downwards, which rather distressed him. But medically, the position in which he carried her was right. When a person faints the head should be below the level of the heart, that the blood may run into the head without calling on the heart for any extra work whilst in its weak state. How often this important fact is overlooked, and a fainting person is propped up in a chair.

Before reaching the house Lucy regained consciousness, and was decidedly astonished to find herself being borne in the arms of a young man. The situation, however, became so embarrassing—though not uncomfortable—in view of all the servants, who had turned out to render help, that Lucy had the presence of mind not to become too conscious before she was safely laid on the sofa.

When the doctor did arrive Lucy had pretty well recovered herself, and he was loud in Charley’s praise: first, for not allowing her to remain lying on the cold ground; secondly, for carrying her with her head down; and thirdly, for sending for him without a moment’s delay.

Mamma had arrived home from her drive, and on hearing all about the accident looked at Charley through ‘rose-coloured spectacles,’ so to speak: in fact, Charley was made much of.

‘Poor Naughty-boy!’ said Lucy; ‘I hope he will soon be all right again; but I am afraid there is an end of our bargain.’

‘It’s very hard, after making you an offer, to have it broken off like this,’ replied Charley, slyly.

‘Oh, but as the poor horse is damaged, there must be an end to business.’

‘Business ended, then pleasure begins. Oh, Lucy, I should like to make you another offer: quite a different one altogether!’ And Charley caught her by the hand in his impetuosity.

‘Oh, you are really too foolish!’ replied Lucy, blushing. But she didn’t really think so.

Word Count: 4152

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Bryce Rosengren

Brooke Farnsworth

Hattie Nickles

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

10 March 2025

Last modified

4 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Original text lacks a period at the end of the sentence. Likely a typo. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | French phrase meaning: a collection of miscellaneous or decorative objects, often with little value. |

| ↑3 | Italian phrase meaning: in a low voice, so as not to be overheard. |

| ↑4 | Literally the fear of water, though during the time it often instead referred to rabies. Fear of water was a common symptom of rabies, and was discussed frequently during the Victorian period as an awareness and fascination with diseases grew. (John K. Walton, “Mad Dogs and Englishmen: The Conflict Over Rabies in Late Victorian England,” Journal of Social History, vol. 13, no. 2, 1979: pp. 219-39. JSTOR.) |

| ↑5 | Italian word meaning: in love, or lover. |

| ↑6 | French phrase meaning: literally, a head-to-head, but often referring to a private or intimate conversation between two people. |

| ↑7 | Original piece has missing end quote mark after ‘tucked up.’ |

| ↑8 | Likely a curse word omitted from the original manuscript. |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.