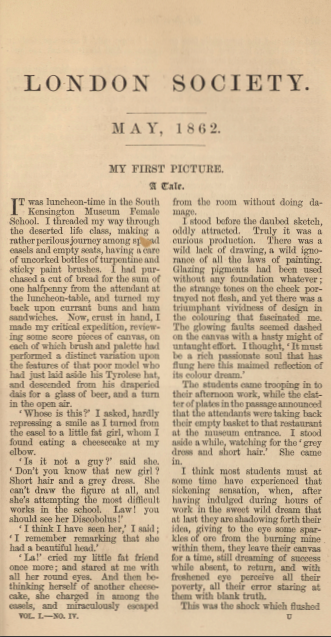

My First Picture. A Tale

by R. M.

London Society, vol. 1, issue 4 (1862)

Pages 289-302

Introductory Note: “My First Picture” is one of the more complex short stories in the typically lighthearted and conservative London Society magazine. The narrative follows many of the conventions typical of the stories in London Society: it involves a romance, a bitter struggle against outside circumstances, and, ultimately, a marriage. However, “My First Picture” goes beyond bland stereotypes. Although a romance is involved, the story revolves around two young female art students living and studying independently in the heart of London at the South Kensington Museum. The museum, now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum, had opened in 1857, just five years before the story was written. The narrative is notable for its depiction of the women gaining an understanding of art and beauty, earning an independent living, and evaluating the merits of both single and married life for female artists.

It was luncheon-time in the South Kensington Museum Female School. I threaded my way through the deserted life class, making a rather perilous journey among spread easels and empty seats, having a care of uncorked bottles of turpentine and sticky paint brushes. I had purchased a cut of bread for the sum of one halfpenny from the attendant at the luncheon-table, and turned my back upon currant buns and ham sandwiches. Now, crust in hand, I made my critical expedition, reviewing some score pieces of canvas, on each of which brush and palette had performed a distinct variation upon the features of that poor model who had just laid aside his Tyrolese hat, and descended from his draperied dais for a glass of beer, and a turn in the open air.

‘Whose is this?’ I asked, hardly repressing a smile as I turned from the easel to a little fat girl, whom I found eating a cheesecake at my elbow.

‘Is it not a guy?’ said she.1The term “guy” was used to denote a grotesque-looking person. ‘Don’t you know that new girl? Short hair and a grey dress. She can’t draw the figure at all, and she’s attempting the most difficult works in the school. Law! you should see her Discobolus!’

‘I think I have seen her,’ I said; ‘I remember remarking that she had a beautiful head.’

‘La!’ cried my little fat friend once more; and stared at me with all her round eyes. And then bethinking herself of another cheesecake, she charged in among the easels, and miraculously escaped from the room without doing damage.

I stood before the daubed sketch, oddly attracted. Truly it was a curious production. There was a wild lack of drawing, a wild ignorance of all the laws of painting. Glazing pigments had been used without any foundation whatever; the strange tones on the cheek portrayed not flesh, and yet there was a triumphant vividness of design in the colouring that fascinated me. The glowing faults seemed dashed on the canvas with a hasty might of untaught effort. I thought, ‘It must be a rich passionate soul that has flung here this maimed reflection of its colour dream.’

The students came trooping in to their afternoon work, while the clatter of plates in the passage announced that the attendants were taking back their empty basket to that restaurant at the museum entrance. I stood aside a while, watching for the ‘grey dress and short hair.’ She came in.

I think most students must at some time have experienced that sickening sensation, when, after having indulged during hours of work in the sweet wild dream that at last they are shadowing forth their idea, giving to the eye some sparkles of ore from the burning mine within them, they leave their canvas for a time, still dreaming of success while absent, to return, and with freshened eye perceive all their poverty, all their error staring at them with blank truth.

This was the shock which flushed and whitened the new girl’s face as she came before her first attempt in the life class. Lonely and suffering she stood in the busy crowd, the half-raised brush drooping in her fingers. While I watched, a smile from some one passing finished her agony. She snatched the canvas from the easel, gathered up her brushes, and with burning cheeks and proudly-downcast eyes, quitted the class.

Ten minutes afterwards I was cutting my chalk in the Antique Room. The ‘grey’ girl was whispering and laughing extravagantly with a certain fair-haired romping lass who was the wildest madcap in the school. Absorbed students raised their heads and smiled, as peal after peal of merriment broke from the corner where the two sat. Some one said, ‘What are you two laughing at?’ Whereupon the blonde lassie cried out, ‘Oh! it’s all Miss Barry. You never heard such absurd stories as she has been telling!’ A few minutes after they fell to fencing with their mahl sticks, and were only warned to order by the appearance of a hand on the curtain which hung between us and the passage.

‘Her disappointment does not prey upon her then,’ I thought. And I almost sanctioned an impatient desire that my own failures could sit as lightly upon me. But in another moment I had retracted the half wish. ‘No,’ I mused, ‘the dark hour heralds full dawn; if we want light we must live through shade.’

Next morning, when rather late I entered the room, I found Hilda Barry (the name on her easel) sitting before her drawing-board, pale and passive, with dark circles under her eyes. She seemed to be of a strangely uneven temperament.

Some weeks passed, during which a slight acquaintance sprang up between us. It began by her springing to my side one day, while I glanced over my sketch-book for a note.

‘Do you design?’ she said, eagerly. ‘Oh, please let me see!’

‘I try,’ said I, with a smile, and showed her the book.

‘I envy you,’ she said, as she returned it, ‘but it is not a wicked envy.’

‘I hope not,’ I answered, smiling again. And then she left me suddenly.

One day I sat watching her in one of her still moods. She is beautiful, I thought. There is a latent beauty which might be richly developed. An idea of colour drifted vaguely through my brain. At luncheon-time, when the room was empty, I went and sought in one of the painting rooms a certain piece of green drapery, with dashes of tawny light and olive shade. I arranged it studiedly from a shelf behind the girl’s seat. It will do, I thought: but stay; I substituted a red pencil of my own for the black one in Hilda Barry’s port-crayon, and then I returned to my work. What a picture I had when the dark head shone against the rich sad folds! The outlines were good. The heavy hair swept short and curly from the round temples; the forehead had a pallor where the dusk curves met it; the dark eyes, often too dead and absent, now had a light, while the crimson pencil wrought beneath them. The cheek, too pale before, gained a ripeness against those tawny lights, and the full under lip shone in red relief from the olive shadows. It was a perfect little study—my vague idea of colour realized. Yes, there was exceeding beauty.

Presently she left the cast which she had been shading and went to her afternoon work at the Antinous.2A hero celebrated by both the Greeks and Romans. We seldom mustered more than half a dozen at a time in the Antique Room. We were in the model week, and it was a lecture day, so that the room, rather thin from the morning, emptied gradually, and at about half-past two o’clock I looked up and saw that its only occupants were Miss Barry and myself. As I glanced towards her, I was struck by her wobegone attitude and expression. She was sitting a little drooped, with her hands lying listlessly in her lap. Her face had that dull pallor, her eyes that shadowy heaviness that remind one of a winter rain cloud, when the desolate night is gathering among highlands.

I obeyed my quick impulse to go and speak to her.

‘Are you unwell?’ I asked.

‘No, thank you,’ she replied, stirring in the slightest degree from her still attitude.

I paused a moment. ‘You have a headache, you are tired out. Do give up and go home!’

She shivered slightly. ‘There is nothing at all the matter with me. I am as well as you. In perfect health.’

I would not be battled off so easily. That the girl suffered I knew. I might not have a right to pry into her trouble, but even a vague sympathy might soothe. I sat down before her, and leaned in a puzzle on my mahl stick.

‘If you are not ill,’ I said, ‘in body, you are in mind. You have not been long at the school, and should not be so easily discouraged. We have all our dark days to grope through. Do you find the figure difficult?’

She glanced drearily at her board, with its false lines and smeared India-rubber marks. That rain-drift look swept across her eyes.

‘I cannot see it,’ she said. ‘It looks right to me, as I have it. Mr. D.— says it is wrong, but I cannot see it.’

‘Let me try. I am not the best mistress, but I have been longer here than you.’

She rose quietly, and I took her seat, and fell to work with pencil and plummet. I gave a lesson as well as I could, showing her where the several points cut the line, how to make the figure stand, how to block out the proportions.

‘I cannot go about it in that way,’ she said. ‘I want to dash at it, and have it at once.’

‘But you cannot, you must creep before you can walk. It is slow with every one. Patience is a surer guide to success than genius.’

Her lips tightened again, and the desolate, half-terrified look came back into her eyes.

I wondered at her. I said, ‘You should not be so very, very despondent.’

‘It is nothing,’ she said, with a return of self-command. ‘I am always dull in the daylight. I cannot bear the day. I long for night—in the night I live.’

‘You were very merry this morning.’

‘Ah! that is excitement. It is to keep me from thinking. If Miss Gilbert were here now, I should be screaming with laughter.’

Strange girl! What should I say to her? Still I thought of my own heart struggles and burned with sympathy. I said, ‘I know exactly how you feel. I have felt so. An utter despair paralyzing all my energies, a blindness, a languor, a bleak, bleak desolation of spirit. But believe me’—and I ventured to take her passive hand—‘these are but the death-throes from which we shall awaken to a new life of light and power. For me, I have suffered all those dying agonies which are racking you at this moment, and now I feel that I am waking. Standing on yonder spot of mat where the chair is, I have swallowed oh! such bitter draughts—but they are healing me. It will be so with you, in a little; only wait and work.’

Thus I went on, making use of the unusual language that rushed upon me, because I knew that she best understood and hearkened to it. For two hours I preached, I scolded, I rallied and cheered her, till the bell startled us both.

I feared I had not effected much good withal. The drear mood never yielded; I got few words and a quiet good-bye when we parted. And yet my trial had relieved me. I felt so as I hastened home.

After that my interest in the ‘grey’ student increased daily. I felt also that though she had shown few signs of feeling my sympathy, yet she came oftener in my way, hovered near me, seldom speaking but seeming to like my neighbourhood. Neither of us made many advances, but a tacit friendship existed between us. She seemed to spend all her time at the school. She was there before me in the morning, she was the last to leave in the evening. If there were no lecture to be attended she would spend the time till dusk in some part of the building. If I went for an hour to the library I was sure to find her knitting her brows over some ponderous book, from which she never glanced. Sometimes I happened on her in the Vernon Gallery, often studying Landseer’s picture of ‘War,’ holding that heavy veil which she always wore, stealthily above her eyes.

One Friday evening Mr. M— had kept us late at the lecture. I had left an umbrella at the entrance, and so went out through the museum, instead of by the male school, which was the shortest way from the lecture theatre. Coming quickly round the last corner, I saw on before me the slight grey figure, little black bonnet, and thick veil of Hilda Barry. She was standing alone, studying very attentively a certain specimen of ‘Wych Elm’ from Scotland, which stands about half-way down the last chamber. I halted as I approached her, for contrary to her usage she moved to meet me.

‘I want to speak to you,’ she said abruptly. ‘The Irish are said to have kind hearts. I think you have, unless your face belies you.’

‘It does not, at all events, in this instance. I will do anything in my power to oblige you.’

She kept silence a moment. Then she said suddenly, ‘Can you direct me to a respectable jeweller?’

‘No indeed. I am a comparative stranger in London. I have never had any dealings with jewellers.’

She half turned silently away.

‘But,’ I added quickly, ‘I can easily learn all about it. I promise to get you the information to-morrow.’

‘That will be too late,’ said she. ‘Look! I want to sell this,’ and she showed a brilliant ring lying in her purse. ‘It must be to-night.’

‘To-night? Oh, surely not to-night! Why, it will be dark in half an hour, you will barely have time to get home.’

‘I am not going home. I have no home: I want to sell this in order to get a night’s lodging. I would not have told it to any one in the world but yourself. All day I have been trying to make up my mind to say what I have said. Utter necessity at last chained me here till you should come up from the lecture. But if you cannot direct me I must go and seek my fortune.’

She said this last with a stern hopelessness of tone sometimes peculiar to her.

‘You shall not get rid of me so easily,’ I said. ‘Come, let us get into the street, where we can talk unreservedly.’ I hurried on and she followed. I gave my ticket and got my umbrella, and then we went down the tiled passage past the restaurant, smelling coffee all the way. As a matter of course my feet took the accustomed road to the bird-fancier’s where I lodged.

‘Where are we going?’ said my companion, as we threaded Brompton Row, meeting omnibuses laden with city men coming home, and barristers from the Temple.

‘To Chelsea, where I live. We cannot talk here for the noise. I am quite solitary in my lodging, and if you will come and take tea with me it will be a real charity.’

Hasty tears flashed into her eyes; she thrust her hand into my arm with an impulsive movement, and we made the rest of our way silently and quickly to our destination.

My heart misgave me as I knocked at the door. My landlady was rather uncertain in her preparations for me; indeed, to do her justice, I was irregular in my hours of return, so that it was not so much her fault. I had resolved to coax my poor little wanderer into confidence, and I felt hotly anxious that her first impressions of my surroundings should be snug and homelike, for these, I thought, would be likely to touch her lonely heart. And so my own bounded as I ran upstairs, and saw through my open door the ruddy firelight capering over the walls. When we entered, I could have hugged my quaint little old landlady, as she came up with the kettle, from her canaries. I suppose my lateness had given her plenty of time, but the fire blazed, the place was tidy, my small tea-tray set upon the dingy green tablecloth, the scanty red curtains were something drawn—in fact, the room was looking its best. I wheeled the old arm-chair to the fire, and ensconced my visitor therein. ‘Sit there, dearie,’ said I.

She looked up half surprised, half grateful at the word of endearment, but I took no notice. I had made up my mind. I took away her bonnet, unpinned her shawl, drew off her boots, and laid her feet upon the fender. She made no resistance. I felt that I was gaining my point—her trust in me was growing.

I unlocked my little tea-caddy and wet—oh! rare event!—three great spoonsfuls of tea. I put the teapot by the fire, and toasted some bread. Butter was an unknown luxury in my quarters, but to-night we should have something better. I ran down and sent my landlady’s little Johnny over to the Italian warehouse for a pot of damson jam. And then I stood a moment irresolute on the last step of the stairs, and thought that I might be wanting to leave that shilling with Mr. Cecil Wood, artist colourman, before the end of next week. But ‘sufficient for the day is the evil thereof,’ I whispered, and sprang upstairs to see that my toast was not burning.3A reference to Matthew 6:34.

I gave her a cup of tea, and some bread and jam, which she ate hungrily.

‘I have eaten nothing since eight o’clock this morning,’ said she.

I was glad to hear her say that. Not glad that she had fasted, but that she had acknowledged it. It sounded like the beginning of confidence.

‘You will tell me all about it, will you not, dear?’ I said, when our meal was over, and I had drawn my chair opposite to hers on the hearth-rug. It was quite dark now, and we had lit no candles, but the firelight was springing through the room.

‘I will,’ she said, with a frankness which I had scarcely hoped for. ‘I will tell you everything, for you have come to me like a good angel. I am not afraid that you will betray me.’

‘You need not,’ I said; ‘indeed I am your friend.’

‘I must be strangely ungrateful to doubt it. My story is soon told.’

She thought a few minutes as if considering how she should begin. It is so hard to take up one’s own history, and tell of it condensedly like a tale. This is what she did tell at last.

‘My father was German, and my name is not Barry, it is Werner. My parents died while I was very young, and until within the last two years my life was spent at school in England. I was heiress to a large fortune—better I had been poor, for I was spoiled and pampered because of my fine dresses and plentiful pocket-money. I grew up with a wilful temper, from which I suffer now. Two years ago, just when I was seventeen, my health became very delicate, and my guardian came and took me away from school. I had only seen him once before, and I did not like him. He told me that he had been my father’s dearest friend, and that he expected I would be like a daughter to him. He was a very kindly-spoken old gentleman, but somehow I could not like nor trust him. We lived in a lonely old manor in the country, we three, my guardian, his maiden sister who kept house, and myself. I was very lonely, moped the days away by myself, and grew sicklier than ever. My only delights were reading and drawing. Drawing at school had been my favourite study. I loved it passionately. I had there, quickly gone through all the weak, good-for-nothing school studies, got prizes, and been lauded as a genius till I began to imagine myself a kind of female Raffaelle.4Revolutionary Renaissance artist, commonly spelled “Raphael.” You may easily realize what an unhealthy life I led in the dull manor with no congenial companion to speak to. I could not endure Miss Selina, with her prying censorious ways, nor my guardian’s oily tongue and furtive eyes. They seemed to have no relations but a certain “dear Alf” who was a captain, away with his regiment somewhere at the world’s end, and was expected home yearly. He was my guardian’s son.

‘I moped and read till I grew as romantic and useless for any purpose of existence as could well be imagined. I knew nothing of real life; I lived among stars and moons and poets’ dreams.

‘Love was the one theme of all the books I read; and an imaginary love became by degrees my household god. “Love” seemed to me a bright unique word of a heavenly tongue which had strayed into this world’s commonplace language. I saw it at night from my window printed in stars over the sky; I spelt it in the moonbeams that stamped their silver characters on the floor of my quaint old-fashioned chamber. Do not think too hardly of my folly in this—remember I had no real natural affections around me: I was lonely, and fond of no one in the world, though my heart ached with a load of unspent love.’

She paused a moment, turned her head slightly from me, and with a heated cheek went on, looking steadily into the fire the while—

‘My health continued weakly: my guardian showed some anxiety. I said, “If you want to keep me alive, sir, let me have lessons in drawing!” I was full of artist’s dreams. I think he was frightened, for he consented.

‘A few days after Miss Selina made an announcement at dinner. She had ascertained that there was a very competent teacher of drawing in the neighbourhood, “a real artist,” who was sojourning in the country, making studies from nature. He was giving lessons in the houses of several high families around, and was universally esteemed a perfect gentleman.

‘Mr. Winthrop was engaged to give me lessons.

‘Winthrop?’ I echoed, starting.

‘Yes, Mr. Frank Winthrop. Before I tell you the rest do look back upon what I have told you already, and think of my life. My new master came to me three evenings in the week.

‘It was summer, early summer—May. My guardian was always out at dinner parties; or if not, nodding over his wine in the dining-room; and Miss Selina always dozed away the evenings. It had been so long a habit in the house not to mind my doings or my whereabouts that things went on now just the same as ever—only, instead of crying with loneliness in the wood, or reading Tennyson in the garden, or moping up in my own room, I was listening to the glowing language that made me intimate with my master’s picturesque thoughts; seeing my Lilliputian art-dwelling swept down by a strong hand, and the wondrous plan of a new heaven-touching palace sketched upon its ruins; receiving lessons which I can never forget; while the summer air brought us the jasmine on its breath, and the blackbirds in the garden sang treble to my master’s deep musical tones.

‘For many months things went on so—I breathed a new atmosphere, health returned to me. I am afraid that I did not learn a great deal, my master’s plan of teaching was so new, I felt so ignorant, and had to begin again at the very commencement. But I had found a friend: my master was kind, gentle, firm; no one had ever treated me as he treated me. He only, of all the world, seemed to feel or care for me. Was it sinful, was it unwise, was it unmaidenly in me to give to this friend, who had bestowed on me new life and strength, all the pent-up affection which no other would have from me, and which was breaking my heart with its might? I have been told that it was all three, but I will not believe it. I cannot think that it was a crime so enormous that it must be expiated by a life of emptiness and sorrow. I did not give my heart unsought: I knew that I was his pet pupil, that my presence gave him pleasure, as his did to me.

‘With his beautiful notions of art, faith, truth—with his soul of genius—his rich fancy and powerful hand—I felt that to be enshrined in his heart must be something like being enthroned among stars. “And this is life,” I said—“how glorious life is!”

‘In those days I had a certain beauty. You may wonder now, but I knew it when after my lesson I ran up-stairs to arrange my hair for tea, and stood before the glass in my white summer frock with eyes shining with happiness and a rose on each cheek. I had never before thought much about whether I had beauty or not: it is only for the sake of those who love us that we prize our good looks; and I had never had any such stimulus to vanity. But now it was otherwise; and at some moments I have felt myself worthy to breathe in a world of love and beauty.

One evening I picked from the floor a little sketch-book, which I thought was my own. I put it in my pocket, and thought no more about it. That night, as I stood at the window in my dressing-gown, I opened the little book to put a rose leaf between its pages: a fine rose was dropping to pieces in a glass on the table. My eyes rested on a sheet which I had never seen before. A head was sketched upon it, exquisitely tinted, with a background of grave mellow drapery. It was a glorious little sketch—my heart swelled exultantly, for it was my own face that I saw on the paper. I laid the little book reverently on the silvered edge of the window, and bent over it in a trance of joy. Here on this tiny page were all my beautiful foreshadowings substantiated—all my heart’s fair prophecies fulfilled: I now felt sure that my master held me dear. Half that night I knelt by the window, steeped to the lips in a sea of happiness, trying to pray, lest God should think me ungrateful, and take the sweet cup from my lips ere it was more than tasted.

‘All this must sound very foolish and romantic to you. It is only while the sacredness of silence and secrecy hangs over things like this that they are real and true: directly they are thrust upon other ears they degenerate into folly and sentiment. I feel it so, but I must tell you that you may understand the rest. In the morning a difficult question occurred to me. How should the book be returned to my master, so that he should not suspect it had been opened? I thought over this long. Would it not seem strange if I employed any one else to give it him, having found it? and even if I did so, how should I see it given him without my face betraying my secret? I made up my mind that I must do it myself: I would hand it to him in a matter-of-fact manner, saying carelessly, “Here, sir, this was found upon the floor yesterday after you left.” The very fact of my delivering the book myself with so much coolness would be sure to prevent suspicion. I did it. I stood five minutes at the library door rallying my courage; it was of no use to tremble. I could not now call a servant to hand Mr. Winthrop his book; I could not wait till he inquired for it, that would be worst of all. At last I went in, and with as much quiet bravery as it was in me just then to summon, presented the sketch-book. Had he taken it as quietly all had been right; but the sudden flash of eyes and flush of forehead overset me. I could not raise my eyelids, and felt the hot blood glazing my eyes and burning my temples. I need not dwell any more on that evening: before an hour I had promised to be his wife.

‘I could not understand why he was so reluctant to speak to my guardian. I would not believe, in my utter ignorance of the world, that any one could be so wickedly unjust as to imagine that Mr. Winthrop coveted my wealth. One morning I went for a ride after breakfast, thinking gladly as I cantered along that to-night I should have a drawing lesson. In my absence my master came to my guardian and told his honest story. In answer he was abused, scorned, and driven from the house with insults. On my return I was met with recoilings and taunts, and ordered to my room till I should be sorry for my sins. Then they came and sneered at me, and accused and raged at me—oh, such horrible things as they said! I did not endure them long: my first stupor of amaze over, I gave rein to my wild temper, and with a whirlwind of passion drove them all affrighted from the room. I locked myself in, and remained in my anguish all day and all night. My one only friend was gone: that was all I realized. He to whom I owed so much had been insulted and reviled in return. As the hours crept on storm after storm of agony broke over my head; and it was only when daylight came that I was worn out and calm.

‘I wrote a little letter to Mr. Winthrop telling him I was true. I bribed a servant to send it to him; but I am sure that she was bribed again, and that he never got it. He never came, never wrote, never appeared again in the neighbourhood. I suppose that he did not think me worth getting insulted for.

‘I will pass quickly over the next nine months. I was hardly nineteen, and yet I felt aged, as if I had lived a long life, as if I had tasted all of joy and sorrow that life could offer me, and was ready for the grave.

‘It was just nine months after this that my guardian’s son, Captain Alfred, came home; and I soon saw that I was expected to marry him. I could not endure him: he was a drawling, conceited, middle-aged coxcomb, whom I despised and detested. It seemed to be all arranged between father and son. The captain assumed a manner towards me which I could not brook. He seemed at first to think it a “doosed boa” that he had to marry the little school-girl in order to get her money; but as there was no other means of laying hands on it, he was prepared to do so. This stage of affairs was revolting enough, but I tried to endure till a crisis should arrive when I could speak my mind. By-and-by, however, he began to pay me attention—to act the lover. He haunted my walks; he followed me about the house and garden; he would not take rebuffs; he laughed at my passions. I had no redress, so I took refuge in my own room. I spent day after day there: often I did not leave it for meals: I had little appetite. Since the captain’s return Miss Selina had been continually purchasing me new dresses, and having them made up for me. These, through spite, I would not wear. I dressed myself always in an old black uniform frock belonging to my school-days. One month I spent almost entirely in my own room, till, through dreariness of mind and confinement, my cheeks grew hectic, and my hands trembled.5“Hectic” means displaying symptoms of a fever. I was nervous, and fancied my room haunted. I could not sleep at night.

‘All at once a feverish reaction came. I longed for society of whatever kind; I dreaded being alone; I wanted excitement.

‘In those days we were a good deal asked out in the neighbourhood. The invitations were regularly sent to me, but I invariably declined them. At last, one day there came cards for a dinner-party, and suddenly I desired to go. I had overheard some one saying that the captain was going elsewhere, and I saw him ride away after breakfast. I resolved to take advantage of his absence, and taste the novelty and excitement I craved. At evening I took (I remember it all so distinctly) a violet silk frock from my wardrobe, and curled my hair over my shoulders. I saw my face looking wildly feverish in the glass, before I descended to the drawing-room. I entered, with my cloak hanging over my arm, prepared to acquaint my guardian with my intention to be of the party. The room was half dark, and I thought empty; but midway on the floor I recoiled in dismay, for Captain Alfred sprang to meet me. He attempted to take my hand, and paid me some hateful compliments. I know not what I said; I believe I screamed out. I was feverish; all my senses quivered with nervous excitement. My guardian and his sister came running in, and a scene followed, too miserable to be detailed. My guardian, in a fury, bade me give up my tempers, and henceforward look on the captain as my husband.

‘I vowed I would not. I seemed to breathe fire; green and red lightning went flying over the walls, flashed in people’s faces, and blinded my eyes.

‘“You talk of fortune-hunters,” I cried, “what is he?” pointing at the captain. My guardian became more and more enraged at this, swore terrible oaths that by my father’s will I must marry his son, or be a beggar. I said no more, but fled from the room. They thought me cowed, and went to their party.

‘I rushed up stairs, and flung myself on my knees, praying wildly to God to open some door of escape from my miserable life. My prayer calmed me somewhat. I rose from my knees, and stared blankly into my future, which seemed as dark and vague as the night around me; feeling that I must do something next, and wondering what that something should be. My room was beautiful at that moment with moonlight; but I saw no beauty in it, only a sickly melancholy light lying among the shadows, like a deathly smile in dead eyes. I stood at the window, and a finger seemed to beckon me, and a whisper to breathe in my ear. A thought glimmered across my brain. I snatched at it, feeling a rush of life coming back to my chilled face. I rang the bell quickly. In lamplight and firelight I could harbour my new idea, and treat it as a substantial guest, but not among these unearthly moonbeams and depressing shadows. My maid brought up my tea-tray and lamp. Janet was the daughter of a neighbouring farmer. I had engaged her when I first came from school. I had grown fond of her, and made her many presents. I believe she loved me in return, and showed her kindliness in many little ways; but she was gay and giddy, and, I fear, not proof against a large bribe. I had learned of late to distrust her.

‘When she had left me, I sat for ten minutes at the table, with my head between my hands. At the end of that time I had made up my mind. I then stirred myself, poured out my tea, and made a better meal than I had eaten for long. When the girl came for my tray, I said, “Janet, I shall want nothing more to-night; you need not come again.” I would fain have asked her assistance, but I feared to do so.

‘I waited only a few moments after her steps had been lost in the distance, and then I took my lamp in hand, and made my way up stairs to a passage little used, but which communicated with several old rooms, now quite musty and deserted. Their furniture was old-fashioned in the extreme; and the tall, narrow wardrobes and carved high-backed chairs had a ghostly look to me. I had only been in them once or twice before. I remembered, however, that there were certain quaint old dresses locked away in some of the wardrobes, which had probably belonged to some of my great-grandmothers or great-grandaunts. Miss Selina kept the keys. Remembering this, I went back, and searched her drawers, possessed myself of a bunch, and sought the ghostly rooms once more. All the queer old keys were tried again and again before I succeeded in opening a door. At last I grew nearly desperate, and listened in dread for steps on the stairs. Hearing none, I made a last effort, gained my point, and opened the largest wardrobe. I rummaged nervously, and with a sinking heart, among dim brocades and faded satins. None of these would suit my purpose. On a high shelf I found a pot of rouge, and a wig of grey plaits. I set these aside; they might be of service; and then, with a desperate energy, I returned to the attack on a neighbouring lock. It yielded, and there, within this second press, I found what seemed to be the earthly apparel of some departed widowed ancestor. Sombre garments hung from the pegs, and folds of crape, and muslin, and bombazine lay on the shelves.6Types of fabrics; crape and bombazine were often used for mourning clothes.

‘I chose a black gown of stiff flowered silk, and a white kerchief to cover the quaint, ill-fitting body; a wide old-fashioned cloak, and a cap and bonnet, which, though queer, and rather antique looking, I thought might pass well enough on an old-world dame of the present day. I took a little rouge from the pot, and left it back on the shelf; gathered the articles I had chosen in a bundle, locked the wardrobe, replaced the keys in Miss Selina’s drawer, and hastened back to my room with my treasures. Having locked the door, it did not take very long to metamorphose me into an antiquated gentlewoman, with grey braided hair, widow’s cap, and rich old-fashioned cloak and gown. I cut my long hair quite short, so that the wig might cover it. I rubbed a faint smearing of rouge over my whole face, which quite altered my complexion, and powdered my eyebrows to match my hair.

‘Latterly I had spent nothing of my allowance of pocket-money. I had thirty pounds in my desk. This I put in my purse, and also concealed some jewels about my person. I took with me the silk dress which I had worn that evening, and a pocket-handkerchief, marked with my name. In fear and trembling I unlocked my door, listened a while on the passage, and then passed swiftly down the staircase, and out of the hall door. I had been to London once, and I knew where to find the station-house, and at what hour a train passed. On my way I flung my dress into the river that skirted the lawn, and wet my handkerchief, and tangled it in the brambles on the hedge. “Let them think what they please,” said I, as I hastened on, “only God forbid that they should track me out.”

‘I had no difficulty in getting my ticket, and soon found myself whirling away on the night-train to London. I often have wondered since at my sensations during that journey. I felt no fear, no misgiving. I only felt that I was free. The moonlight flashed in at us as we sped along, and I now thought it radiant and cheering. But the carriage-lamp soon quenched it. My fellow-travellers were an elderly lady and gentleman. The latter dozed in the corner, while the former worked busily at crochet. She seemed inclined to converse, and I feared to answer her. I had been counted a good mimic at school, and now I imitated Miss Selina’s sharp voice. Then, lest she should oblige me to keep up a conversation, I pretended to sleep also, and so the journey passed.

‘Even when standing on the platform, alone and unfriended in London, I felt no fear of anything. I asked a porter, in my assumed voice, to direct me to some quiet place at hand for the night. He did so, and I knew by the manner of the chambermaid who attended me that my disguise was complete. Next day I took a cab, and told the man to drive me out to Kensington, and to stop at the first lodging-house he happened on in that neighbourhood. I inquired at several, and at last engaged a room in a respectable-looking house in — Street. My landlady was very civil, and at once I found myself settled down in London.

‘But, having thus successfully made use of my disguise, how was I to get rid of it? I could not attend classes at the Kensington Museum in my character of antiquated gentlewoman, and to attend those classes I had resolved. I fancied, in my utter ignorance of money matters, that my store would last me a long time, and that, by selling an ornament now and again, I could, with economy, manage to live, till I should be able to earn something in some way as an artist. What a fool I was! I expected to be able to draw at once everything which I attempted. I had a vague idea that I should get into an atmosphere of art at the Museum, and be directed in the right way to earning.

‘I had now to exert my ingenuity again. I purchased some grey carmelite stuff, brought it home, and made it up in secret, to fit myself. I then informed my landlady that my niece was coming up from the country to attend classes at the Kensington Museum, and that, having found her room comfortable, I would send the young lady to board with her. I also went to Mr. B—’s office, and procured a class ticket of admittance to the Museum for a young lady called Hilda Barry. I bade my landlady adieu one morning, desiring her to expect my niece at a certain hour in the evening, and then walked a long way into the City, past Temple Bar two miles, I am sure. When I thought I had walked far enough, I went into a shop, bought a bonnet (the same which I wear), and this shawl. I had brought the dress with me. I then called a cab, and got in with my parcels, and desired the man to drive me to No. 7, — Street.

‘As soon as we had started I drew down the blinds, pulled off bonnet, wig, cap, gown, rolled them up in a bundle, dressed myself quickly in the clothes I now wear, rubbed the rouge from my face with my handkerchief, smoothed my hair with a side-comb, and tied on my bonnet and veil. When we arrived at the house, and the cabman opened the door for me, I could scarcely keep from laughing at his face of consternation. He stammered out something about the “old lady.” I told him that the old lady had engaged the cab for me. He still stared, but as he found his money all right, he at length mounted his box, and drove off.

‘It was rather amusing to see how completely my landlady had been deceived. She spoke to me often about my aunt, said she was a fine, active old lady, and that I resembled her something.

‘I presented myself at once at the Museum. I had not been there for many days before my hopes of earning were dashed to the ground. I found myself on the very lowest step of the ladder, while even those who seemed to me at the highest, appeared to count themselves only beginners. It was of little use that I could design illustrations for the “Idylls of the King,”7A cycle of poems by Alfred Lord Tennyson. and make them look well to uncritical eyes, when I could not attempt the “Antinous,” for drawings of which others were taking medals. I saw the students smile at my miserable attempts. I knew, I saw, I heard all around me the assurance that years must pass ere I could earn. And where should I be in a short time? How short I dared not think. An indescribable agony of terror overwhelmed me at times. I feared to meet my landlady. The money went fearfully fast. I worked night and day. I dreaded to be anywhere but in the Museum. Mr. B— noticed that I worked unceasingly. He spoke kindly to me, and warned me against injuring my health. One night he found me working in the Antique Room alone, and talked to me in a gentle, friendly way. When he had gone, I laid down my head, and cried in desolation. I almost wished that I could injure my health, and die while yet my landlady looked on me humanely, and would give me shelter. Better far, than to wander an outcast in the merciless city, and in the end die of starvation.

‘Only at night, when I went home, did I feel secure for a few hours at least. In the mornings I hated the light, not knowing what the day might bring. At last my very energy gave way. I could not work for the haunting terror of what might lie before me,—what sufferings, what temptations, what outcast wanderings! It was to scare these phantoms that I laughed and romped with that lighthearted girl, who thought me as glad and gay as herself. You, only you, seemed to penetrate and sympathize with me. I feared you for it. I yearned for sympathy, but I dreaded to attract attention. Much as I shrank from the future before me, it seemed endurable, compared with that which must await me, did my guardian discover me.

‘I sold my jewels one by one. But even my ignorance was convinced at last that I had received nothing like a fair price for them. I began to distrust my landlady, and she to distrust me. I thought she charged me extortionately on every small pretence, and I am sure that she began to suspect my difficulties. I received no letters, I had no visitors, I was scantily supplied with every necessary. She had opportunity of letting her room to better advantage, and threatened to turn me out, if I did not pay at once certain bills to which I objected. She told me this morning, that if I did not settle the account to-night on my return, I should not sleep under her roof. She is a cold-hearted woman, and I did not know how to cringe or beg. In my despair I applied to you to-night. You have been a true, true friend. I know you will not betray me. If I have acted unwisely I have been bitterly punished for it. God help me! The future is all a blank.’

She ceased speaking, and I saw the tears shining in the firelight, as they fell like rain into her lap. I knelt beside her, and drew her head down on my shoulder.

‘Have no fear,’ I whispered. ‘The worst is past. God has brought you so far, and will not desert you. Stay here with me. I am poor, poor enough, God knows, but we will work together and plan—and I have no doubt earn too, before long. At all events, we will rise or fall together.’

She threw her arms round my neck, and cried passionately, and kissed my hands.

I sat up on my pillow that night, and watched by the starlight Hilda’s pale beautiful face, slumbering like a baby’s beside me. I thought over her strange story, and strengthened my resolve to assist her. And then there arose a fear in my heart, and I thought of my widowed mother at home, with her slender income, and little Elsie with her longing to go to school. But I shook the fear from me, and turned to sleep again, murmuring, ‘The Lord will provide.’

‘Hilda,’ said I one morning, ‘have you any objection to sit for me?’

She smiled and asked why.

‘Because I want to venture a little picture for this year’s Academy Exhibition.8Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts. I cannot afford a real model; you would just do.’

She laughed, and agreed.

She had improved wonderfully since that crisis of her distress. We had sold her ring, and settled accounts with the hard landlady, and we lived and worked together. Hilda progressed now at her school studies. She designed rapidly, and by my advice spent part of her time in learning to draw on wood. She also improved at painting, and her work in the life class provoked no more smiles.

She never alluded to Mr. Winthrop; but I knew she was quite ignorant of the fact that her former master was one of the most rising artists of the day. She never looked in newspapers or Art catalogues, or she might have seen his name figuring conspicuously in both. I at first wanted her to let me write to a lawyer and state her case, as I felt sure that her right to her father’s property could not depend on her marriage with her guardian’s son. But Hilda showed so much distress at the idea of discovery, and persisted so steadfastly in her belief that it would only bring a renewal of her old persecution, that I let the subject drop.

One night, while I lay awake, a bright idea occurred to me, and I devised a little scheme. The first step towards its development was that question to Hilda—‘Have you any objection to sit for me?’

I procured a bit of drapery even better suited to my purpose than that which I had found in the school. I longed to ask Hilda the colour of those grave, mellow folds, which she had described in Mr. Winthrop’s sketch. But I dared not excite her suspicion of my purpose. I studied the hues and shades, and at last satisfied myself that I had hit upon the right tint and tone.

In the early spring days we went to work. Hilda made an excellent sitter. She fell into a dream as soon as my brush began to move, and unconsciously gave me the very rapt, half-melancholy expression I wanted to convey. I gave her a sparing reflection from that ‘rose on each cheek’ which she had told of so naïvely. I gave her brow its transparent pallor, her eyes their dusky shine, and her lips their full meed of rich brilliant dye. I succeeded beyond my hopes of making the picture ‘a thing of beauty.’ It grew under my hands; I wrought my purpose into it; and every day I said, ‘It is good.’9Reference to the Biblical creation story; see Genesis 1. Olive and crimson, amber and dusk, wove themselves into harmony like the strains in a choral burst of music. And the likeness was there, appealingly good. Hilda started in fear, when after the last touch she saw her double. ‘If her guardian should see it? Or if—’ she flushed and turned away. I knew what her thought was; she was too unselfish to finish her objection. She would not damp my hope. It was ‘beautiful, too beautiful,’ she said.

May came. The picture was sent, and, blessed chance! accepted. We went one day, and saw it in the Exhibition. Hilda wandered nervously among the pictures, hardly daring to raise her veil. Another day I made an errand into town alone, leaving her at her work, and sought the Academy again. I sat down in front of my picture, and for some hours watched all who passed, and all who gazed, hearing their remarks.

I had been there long, when a young man came and took his stand between me and my work. Many men, young and old, had done the same, but I noticed this person especially, as he seemed to bestow all his attention on my small picture, unheeding its more prominent and attractive neighbours. I rose, and walked past and near him. Yes, he certainly was studying my picture. I returned to my seat. It was early, and the rooms were not very full. Our end was almost deserted. I saw him take something from his pocket and study it in his hand, then again gaze on the picture. After a long time he turned and walked away with a disturbed countenance. As I followed the pale stern face, a sudden gleam of recognition flickered through my brain. I struggled to recollect where I could have seen him before. And then association went to work, and gradually a mist of smoke seemed to rise, pierced by a single spark of fire, and encircled the head. Then memory presented me with a familiar sketch—Hilda standing still in the Vernon Gallery, looking stealthily from under her veil at that picture of ‘War’ by Landseer.

Now it was all clear. The face before me was strikingly like the handsomer of the two heroes in that picture. ‘This must be Mr. Winthrop,’ I said, and my heart rose to my mouth. Where had he gone? Ah! there he was again, speaking to the person who sells the pictures. He took a catalogue from the table, and looked hurriedly through it, passed his finger down a page, shut again and replaced it, hastened out of the room and down the steps.

I gathered my shawl around me, and was about to follow his example, when I saw some one approach and place the ticket ‘Sold’ on my picture. Positively on mine. I could scarcely believe my eyes. Twenty guineas wherewith to replenish our scanty purse! I stood in the fast-crowding gallery, seeing no one, blinded with sunshine. I hurried to the green-baize table, and inquired who was the purchaser of the picture just then ticketed. ‘A gentleman who had just left—Mr. Winthrop, the artist.’

I had heard enough, and sped home with a light heart. I flashed in at Hilda, where she sat poring over her work in the little Chelsea sitting-room, looking dull and weary in the midst of a streak of May sunset gloss.

‘Oh! Mave,’ she cried, dropping her block in bewilderment, as I flung off my bonnet and danced about the room with delight, ‘it is sold? Oh, dear, is it sold?’

‘Sold! sold!’ I echoed, stopping my pirouettes, putting my hands upon her shoulders, and looking in her eyes. ‘Really and positively sold—disposed of for evermore!’

And then we had a great hug, and the tears came trickling over my face, whether I would or not. It was very ridiculous, because I was laughing all the time. No wonder Hilda stared at me. She thought it was all about the success and the money.

‘Now, my dearie,’ said I, after we had subsided a little into our usual strain of conversation, ‘I have reason to expect that the person who bought the picture may call here soon, perhaps this evening, so we must have the room very tidy, also our hair.’

‘Who is he?’ asked she with interest.

‘Oh, a gentleman. How should I know his name? But he will call, and then I suppose we shall hear.’

‘Perhaps he is going to order another picture,’ suggested my innocent Hilda; and that was the last we said about him.

I spent a good hour, arranging our room to the perfection of neatness. In the fulness of my heart I had bought a large bunch of violets from a sad little Irish girl who haunts the Strand. I placed them in a pretty glass on the window table where Hilda sat at work. She laughed at my extreme particularity about her appearance. I arranged her curls myself in their most picturesque style, and insisted that she must put on a fresh linen collar of tiny dimensions, although she urged that the one she wore was not the least bit soiled, and hinted broadly at our washerwoman’s bill.

‘You are growing quite magnificent on the strength of your twenty guineas,’ she said. And then, having submitted, she went on with her work. I watched her a few minutes with satisfaction, and was hard-hearted enough to feel content that the pale, tired face looked touching, under the shadow of the cloudy hair.

I then retired to our inner closet, and left Hilda to her fate.

The clock struck seven, and quick upon its jingling tones came a rat-rat-tat-tat to the door. Hilda cried out to me, ‘Mave! Mave! here is your visitor.’

‘Stay, like a good girl,’ I answered; ‘I shall be ready in an instant.’

Scarcely had I spoken when a step was on the landing and a hand on the door.

I had provided myself with a chink through which to ascertain if the new comer was indeed the person whom I expected. I saw Hilda rise with her usual air of reserve and dignity towards a stranger. She turned her face to me and to the door. I saw the crimson blood flash over her face, and in a breath she was wan as the moon. She opened her lips to speak, her dilated eyes deadened and closed, and at once she fell heavily upon her face on the floor.

I was terrified; I had not counted upon this. Hilda was usually so strong to bear and so self-governed. But I should have remembered that she was not robust, and tired after the day’s close work. I had been wrong not to prepare her.

I hardly remember what Mr. Winthrop did or said. I only know that his face was very white, and his lips quivered as he asked me for some water, in God’s name. We were not kept long in uneasiness. Hilda recovered quickly. I shall never forget her smile—so pallid, yet so radiant that it seemed unearthly, when she saw her old master’s face bending over her with anxious tenderness.

Hilda is now Mr. Winthrop’s happy little wife. They have got a pretty house in Brompton, and my blessed picture hangs in the drawing-room. They are both very much annoyed at my fidelity to my old birdfancier, while a little jewel of a room lies vacant for me at Honeysuckle Terrace. But I stay on in my old lodging. It suits me better, my plain dress, and my bonnet seldom renewed; also my necessity for hard work, and the hoarding of time. But I do love to go to see them. Hilda’s house is the neatest, her drawing-room the daintiest, her kitchen the best ordered, and her bedroom the most refreshingly tidy of any as yet known to me, although their young mistress does stain her fingers with paint in her husband’s studio for several hours during the day. I don’t know how it is. I used to say to her, ‘Hilda, you are bound to be a slatternly wife, being an artist;’ and she has answered, laughingly, ‘Oh, certainly: you shall see what a sloven I am going to prove myself.’

Perhaps it is that Hilda works at her easel during those hours which most ladies spend in their dressing-rooms, paying visits, shopping, or reading novels. I don’t know. But she is no sloven, when I, having come for tea, met her in the hall of a winter evening, in her warm-coloured dress, her trim cuffs and collar, her little silk apron, and, though last not least, the sunshiniest of welcoming smiles. Mr. Winthrop is as kind to me as if he were my brother, and it is chiefly owing to him that I am beginning to succeed as an artist.

I have reason to believe that the cruelty of Hilda’s guardian will speedily be exposed, and her property placed in her husband’s hands. This will make them very rich indeed, but it cannot make them happier than they are.

They have promised to come with me on a visit to my West Irish mountain home next summer. When the lilies are full blown on the blue lake under our cottage gable, I shall have looked in my mother’s face, and held little Elsie in my arms.

R.M.

Word Count: 10499

Original Document

Topics

- Christian literature

- Didactic literature

- Love story/Marriage plot

- Social problem fiction

- Women’s literature

- Working-class literature

- Realist fiction

- Artist

How To Cite (MLA Format)

R. M.. “My First Picture. A Tale.” London Society, vol. 1, no. 4, 1862, pp. 289-302. Edited by Emily Hubbard. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 5 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/my-first-picture-a-tale/.

Editors

Emily Hubbard

Heather Eliason

Rachel Housley

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

5 June 2020

Last modified

5 July 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | The term “guy” was used to denote a grotesque-looking person. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A hero celebrated by both the Greeks and Romans. |

| ↑3 | A reference to Matthew 6:34. |

| ↑4 | Revolutionary Renaissance artist, commonly spelled “Raphael.” |

| ↑5 | “Hectic” means displaying symptoms of a fever. |

| ↑6 | Types of fabrics; crape and bombazine were often used for mourning clothes. |

| ↑7 | A cycle of poems by Alfred Lord Tennyson. |

| ↑8 | Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts. |

| ↑9 | Reference to the Biblical creation story; see Genesis 1. |