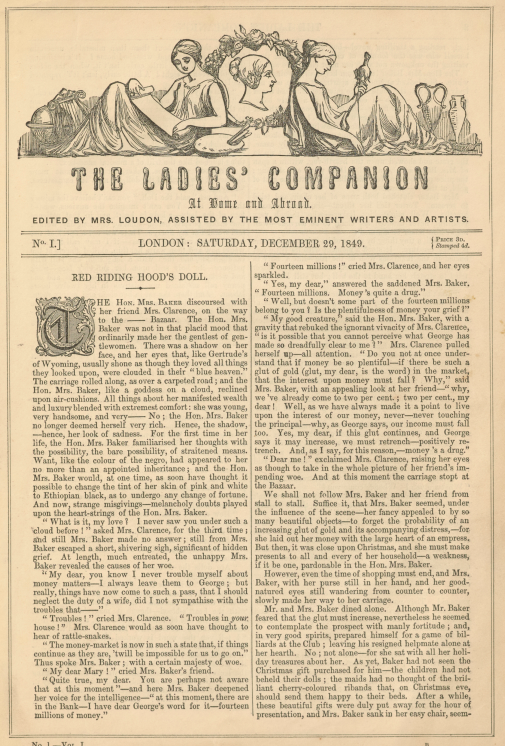

Red Riding Hood’s Doll

The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad, vol. 1, issue 1 (1850)

Pages 1-3

Introductory Note: As the lead article in the first issue of The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad, “Red Riding Hood’s Doll” has much to tell us about the tone and aim of the journal. The narrative is a moral tale addressing the plight of poor needlewomen, a common topic in reform discourse of the time. The tale combines social realism, economic commentary, and whimsical fantasy in its insistence that well-to-do women should understand how their actions contribute to cycles of poverty and should consider ways to intervene. In its combination of social realism and fantasy, the story echoes elements of Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol.”

Often expressing a genuine concern for the poor and recognizing a woman’s role in societal change, “Red Riding Hood” authored the opening article in subsequent issues of the journal.

Advisory: This story contains racist attitudes.

THE HON. MRS. BAKER discoursed with her friend Mrs. Clarence, on the way to the — Bazaar. The Hon. Mrs. Baker was not in that placid mood that ordinarily made her the gentlest of gentlewomen. There was a shadow on her face, and her eyes that, like Gertrude’s of Wyoming, usually shone as though they loved all things they looked upon, were clouded in their “blue heaven.”1Thomas Campbell, “Gertrude of Wyoming.” This Scottish poem references a Pennsylvanian battle in which American revolutionaries were attacked by Loyalists and Native Americans. The phrase “blue heaven” is not found in the current version of the poem, although it may be a paraphrase of line 108: “in Gertrude’s eyes, their ninth blue summer shone.” The carriage rolled along, as over a carpeted road; and the Hon. Mrs. Baker, like a goddess on a cloud, reclined upon air-cushions. All things about her manifested wealth and luxury blended with extremest comfort: she was young, very handsome, and very—No; the Hon. Mrs. Baker no longer deemed herself very rich. Hence, the shadow,—hence, her look of sadness. For the first time in her life, the Hon. Mrs. Baker familiarised her thoughts with the possibility, the bare possibility, of straitened means. Want, like the colour of the negro, had appeared to her no more than an appointed inheritance; and the Hon. Mrs. Baker would, at one time, as soon have thought it possible to change the tint of her skin of pink and white to Ethiopian black, as to undergo any change of fortune. And now, strange misgivings—melancholy doubts played upon the heart-strings of the Hon. Mrs. Baker.

“What is it, my love? I never saw you under such a cloud before!” asked Mrs. Clarence, for the third time; and still Mrs. Baker made no answer; still from Mrs. Baker escaped a short, shivering sigh, significant of hidden grief. At length, much entreated, the unhappy Mrs. Baker revealed the causes of her woe.

“My dear, you know I never trouble myself about money matters—I always leave them to George; but really, things have now come to such a pass, that I should neglect the duty of a wife, did I not sympathise with the troubles that—”

“Troubles!” cried Mrs. Clarence. “Troubles in your house!” Mrs. Clarence would as soon have thought to hear of rattle-snakes.

“The money-market is now in such a state that, if things continue as they are, ‘twill be impossible for us to go on.” Thus spoke Mrs. Baker; with a certain majesty of woe.

“My dear Mary!” cried Mrs. Baker’s friend.

“Quite true, my dear. You are perhaps not aware that at this moment”—and here Mrs. Baker deepened her voice for the intelligence—“at this moment, there are in the Bank—I have dear George’s word for it—fourteen millions of money.”

“Fourteen millions!” cried Mrs. Clarence, and her eyes sparkled.

“Yes, my dear,” answered the saddened Mrs. Baker. “Fourteen millions. Money’s quite a drug.”

“Well, but doesn’t some part of the fourteen millions belong to you? Is the plentifulness of money your grief?”

“My good creature,” said the Hon. Mrs. Baker, with a gravity that rebuked the ignorant vivacity of Mrs. Clarence, “is it possible that you cannot perceive what George has made so dreadfully clear to me?” Mrs. Clarence pulled herself up—all attention. “Do you not at once understand that if money be so plentiful—if there be such a glut of gold (glut, my dear, is the word) in the market, that the interest upon money must fall? Why,” said Mrs. Baker, with an appealing look at her friend—“why, we’ve already come to two per cent.; two per cent., my dear! Well, as we have always made it a point to live upon the interest of our money, never—never touching the principal—why, as George says, our income must fall too. Yes, my dear, if this glut continues, and George says it may increase, we must retrench—positively retrench. And, as I say, for this reason,—money’s a drug.”

“Dear me!” exclaimed Mrs. Clarence, raising her eyes as though to take in the whole picture of her friend’s impending woe. And at this moment the carriage stopt at the Bazaar.

We shall not follow Mrs. Baker and her friend from stall to stall. Suffice it, that Mrs. Baker seemed, under the influence of the scene—her fancy appealed to by so many beautiful objects—to forget the probability of an increasing glut of gold and its accompanying distress,—for she laid out her money with the large heart of an empress. But then, it was close upon Christmas, and she must make presents to all and every of her household—a weakness, if it be one, pardonable in the Hon. Mrs. Baker.

However, even the time of shipping must end, and Mrs. Baker, with her purse still in her hand, and her good-natured eyes still wandering from counter to counter, slowly made her way to her carriage.

Mr. and Mrs. Baker dined alone. Although Mr. Baker feared that the glut must increase, nevertheless he seemed to contemplate the prospect with manly fortitude; and, in very good spirits, prepared himself for a game of billiards at the Club; leaving his resigned helpmate alone at her hearth. No; not alone—for she sat with all her holiday treasures about her. As yet, Baker had not seen the Christmas gift purchased for him—the children had not beheld their dolls; the maids had no thought of the brilliant cherry-coloured ribands that, on Christmas eve, should send them happy to their beds. After a while, these beautiful gifts were duly put away for the hour of presentation, and Mrs. Baker sank in her easy chair, seemingly reading a thrilling novel—but really inquiring of herself who was the founder of clubs, at the same time visiting the unknown not with her most charitable wishes.

The Hon. Mrs. Baker leapt from her chair, turning very white. She looked around the apartment. She saw nobody,—and yet, she could not be mistaken, she had heard a slight, feeble cough—a cough as from a sickly babe. No; it must be her fancy—she would proceed with her book. Again the sound—again and again!

Mrs. Baker, paler than before, slowly laid down her book,—and with one hand grasping her chair looked at the rug; for it was thence the sound distinctly came. The hollow coal suddenly fell in, the flame leapt up in the grate and showed upon the hearth-rug, within a span of Mrs. Baker’s foot,—a Doll, a Doll, price one shilling; the price paid by the Hon. Mrs. Baker, despite the glut of gold, at the — Bazaar.

Mrs. Baker clutched both arms of her chair, and tried to scream. Terror tied her throat—she could scarcely breathe. Well might Mrs. Baker—who, though very beautiful, never asserted her claim to be nervous—well might Mrs. Baker be alarmed.

The Doll, a tiny thing by virtue of its price, was become a living creature. It stood a moment with its little feet buried in the luxurious wool of the rug—like a fairy in clover—and then bobbed a homely curtsey. Mrs. Baker tried to stretch her hand to the bell; but still like stone it held her chair.

“Don’t be afraid, ma’am,” said the Doll in a thin, clear silver thread of a voice, and though Mrs. Baker was at first more alarmed at the sound, there was something in it that carried confidence to her heart. In a few minutes, so very sweet was the voice of the Doll, and Mrs. Baker had subsided from dismay to wonder. The Doll—it had a very pretty delicate face, with more meaning in it than is commonly found in dollhood—smiled, but somewhat wanly; for its features, though so pretty, were a little pinched; and its eyes were lustrous—but not sparkling, happy.

“You had forgotten me,” said the Doll, “but then, I know—I’m so little; and little folks are apt to be forgotten: ‘tis that forgetfulness that does such mischief. Yes; the wax dolls, the fine lady dolls, they’re gone to bed in their silver paper—but as for poor little me,”—

“I’m sure,” said Mrs. Baker, and she wondered at her own voice, “I’m sure I had no wish to neglect you. I thought you were with the others. I had no wish”—

“I’m sure of that,” said the Doll. “You have no wish, no; ‘tis only forgetfulness, but that’s it—that’s it,” said the Doll, with melancholy emphasis.

“Strange creature!” cried Mrs. Baker, trembling anew. “What are you? Whence come you?”

“Don’t be alarmed,” said the Doll, “indeed I wouldn’t frighten you.” Then with sudden vivacity, the Doll asked, “Will you hear my history?”

Mrs. Baker waved her hand—she would hear it. Whereupon the Doll, with a little jump, sat itself upon the edge of the velvet foot-stool before the wondering lady.

“I will tell you my origin and history up to the present time,” said the Doll, “but I wish I could see you smile, and sit comfortably, for indeed I didn’t come to distress you.” Mrs. Baker forced a smile, and leant back in her chair. The Doll began its history.

“I was manufactured by two little boys about seven years old. They put my limbs together, when I was sent away, and a little girl about nine painted my face, and another little girl, having curled my wig, put it upon my head, and another poor little child”—

“Nay, I know all about the making of dolls,” said Mrs. Baker, “you may skip that.”

“Ha, my dear lady,” cried the Doll with a deep sigh, “that is very true; no doubt; but did you never think how sad and very sad it was that children should be doll-makers for children? That for the little workers there should be no childhood—that what are toys to other happier children, beautiful toys calling forth their gentlest, sweetest sympathies,—should be things of drudgery, with no other thoughts about them than miserable, uncertain food, certain rags, and wretched home? It’s beginning the tragedy of life a little early, isn’t it, when the actors are only seven or eight? A little early, isn’t it?” repeated the Doll.

“It is early,” said the lady, with a slight flush. “Go on.”

“Well, I’ll skip a good deal as you wish it, and come to the woman that drest me. I’m very fine, am I not?” asked the Doll. “Beautiful scarlet silk petticoat—charming velvet body. My apron, too, of such very pretty lace, and my hat and feather such taste in it! Why, many a lady might dress herself after me, and carry off all the hearts from a fancy ball,—all of ‘em,”—and the little thing laughed like the trill of a musical snuff-box.

“Proceed,” said Mrs. Baker, for she became more alarmed at the mirth of the doll, than at its earnestness. “Pray, go on.”

“And yet,” said the Doll, “you can’t believe the misery that drest me. You can’t imagine the anxious, wasted face of the lady—a lady in heart, and in that patience that makes poverty heroic—that for one long day, worked and worked at my finery. There was not a speck of fire in the grate, and my mistress—if I may call her so—would now and then warm her thin, chilled fingers at the candle-flame, and then with a long sigh, but still with patience—its holy seal upon her suffering face—work and work. One cup of thrice-drawn tea leaves, and one penny roll sustained my mistress in her twelve hours labour. And there she sat in her clean and empty room, with not a soul to comfort her—with nought but the thought of God to strengthen her, with no one but God’s angels—for they do come in emptiest rooms—beholding her!”

“Go on,” said the lady, “pray go on.”

“When my mistress had drest me fine as you see, she crept out to sell me. It was very, very cold, and I felt her tremble as she pressed me under her thin shawl, and glided along the pavement that chilled her almost shoeless foot. Well, fair lady,” said the Doll, “fair lady, so very fair and gentle, you seem more like a flower than”—

“No compliments,” said Mrs. Baker. “Facts, no compliments.”

“You shall have facts,” said the Doll, sharply. “Well, my mistress sold me. She parted with her labour of twelve hours. Work done on thrice-drawn tea leaves and penny roll. She sold me; and deducting money for petticoat and body, hat and apron, needle and thread, and such trifles—trifles that are to such workers giant miseries—she made clear profit out of me, me who was sold, price one shilling—she made profit,”—here the Doll paused, and clasping its little hands, and raising its little earnest face to the face of Mrs. Baker, asked very slowly—“How much do you think she made?”

“How much? I have not the least idea,” said Mrs. Baker. “How much was it?”

“Fourpence,” said the Doll.

“Fourpence!” echoed the Hon. Mrs. Baker.

“Fourpence,” repeated the Doll, “there is such a glut of money.”

“Are dolls the children of such misery?” said Mrs. Baker, musingly.

“Misery!” cried the Doll, “why the word is stitched and stitched in this glorious city—daily stitched by twenty thousand needles. Stitched in thread, scarlet with the heart’s-blood—though it may show no such colour to the eye of trade,—but scarlet, no lighter than scarlet to the eye of heaven! Misery!” cried the Doll, “I tell you the word is worked almost wherever the needle passes. In silks, in satins,—in ball-room skirts—in funeral hoods; in the coat the soldier marches in—in the jacket the felon works in—in the livery that badges the lackey, in the waistcoat that warms the calculating heart of ‘the poor man’s friend.’ Still misery—misery in millions of stitches—though voiceless, still misery.”

“What’s to be done?” said the lady in a despairing tone.

“I’ll tell you,” said the Doll.

“Oh, do! Pray do,” cried the Hon. Mrs. Baker.

“There are some thirty thousand helpless women, it is calculated,” said the Doll, very earnestly—“thirty thousand, starving, withering—worse than withering. Let them depart and let them be carried where food is plentiful—where comfort, and the best dignity of domestic life await them.”

“Thirty thousand; but it is not possible”—

“Much, very much is possible,” said the Doll, its manner becoming elevated with its theme. “Almost every thing is possible that is for human good, if human energy so wills it. Attend. You can remove these thirty thousand forlorn creatures—sisters in a common humanity and in the tremendous future. ‘We are all equal before the throne of God!’ said a good queen a few days since—a queen, now crowned with everlasting stars—”

“Go on,” said the lady.

“And that you, the rich, may in the great future be equal with the poor—that you may not be below them, the martyrs of poverty, who, by heroic patience here, shall win the bright hereafter,—see that you descend to them now; that you avouch common affection with them, vindicate common sympathy, and show, and take delight in showing, noblest sisterhood!”

“But how—but how?” cried the lady vehemently. “How aid so many thousands?”

“The meanest may do something. For fifteen pounds a suffering sister may be carried beyond the sea to a region of plenty. Say that five, ten, twenty, if you will—nay, fifty,—a hundred,—put together fifteen pounds; select their one sister emigrant. In this way, how many ones may be preserved and lastingly comforted?”

“I see—I see,”—said the lady.

“Take a single case,” said the Doll. “Here is poor Perdita—a miserable needlewoman, striving with her best heart against temptation,—and with hunger and want of every kind, with clothing insufficient to fence her from the elements, still heroically good. In the misery that devours her, she pays the noblest tribute to the shrine of chastity. She withers, but she withers pure. You are a rich lady—take Perdita. Pay her fifteen pounds. Send your offering to the Antipodes—a noble one in a chaste, and kind, and striving heart.2Antipodes refers to Australia. ’Twill be something when you go to rest, to think that your Perdita, now a wife and mother, it may be,—is stirring in her happy home; preparing, in the Bush, her good man’s mid-day meal. It will be pleasant, good as a romance, and then true, in fancy to follow from month to month the progress of Perdita, and now and then to receive from her a written assurance, a real paper document, telling her happy fortune, and with it the happiness of your own rewarding conscience.”

“Indeed, there is something in this,” said the lady.

“Try it,” replied the Doll. “If you’re not rich enough to ship at your own cost, Perdita, have a friend—two, three—in the venture. The venture is a holy one, for it is God’s own merchandise, snatched from misery—it may be, pollution, and freighted for happiness and peace.”

“I’ll have a Perdita all to myself!” said the Hon. Mrs. Baker, leaping from her chair.

“My dear!” cried Mr. Baker, returned from his Club.

It was plain that the Hon. Mrs. Baker had fallen asleep over the thrilling novel—the novel of the season—the novel of absorbing interest, that, once opened, it was impossible to put down. Nevertheless, she could almost have vowed that she had had an interview with the shilling doll that lay, like any other doll, price twelvepence, on the hearth-rug, where it had fallen, unnoticed, from her heap of Christmas presents.

Suffice it—Mrs. Baker has selected her Perdita; and in a few days will ship her noble—her solemn venture. Not unprofitable, even in a dream, was the short sermon of what called itself

RED RIDING HOOD’S DOLL.

Word Count: 3207

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Red Riding Hood. “Red Riding Hood’s Doll.” The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad, vol. 1, no. 1, 1850, pp. 1-3. Edited by Briget Elliott Nelson. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 3 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/red-riding-hoods-doll/.

Editors

Briget Elliott Nelson

Isaac Robertson

Alayna Een

Cosenza Hendrickson

Leslee Thorne-Murphy

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

23 July 2020

Last modified

2 March 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Thomas Campbell, “Gertrude of Wyoming.” This Scottish poem references a Pennsylvanian battle in which American revolutionaries were attacked by Loyalists and Native Americans. The phrase “blue heaven” is not found in the current version of the poem, although it may be a paraphrase of line 108: “in Gertrude’s eyes, their ninth blue summer shone.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Antipodes refers to Australia. |