The Corsican Brothers

by Finch Mason

Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches; a Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British and Foreign Sport, vol. 2, issue 4 (1885)

Pages 273-282

Introductory Note: “The Corsican Brothers” is a humorous tale about two competitive twin brothers in the latter part of their lives. In an attempt to resolve one of their wagers, they participate in a horse race to decide the winner. The tale is illustrated by its author, Finch Mason.

On two separate farms—each farm being situated on the top of a hill, and each hill staring one another hard in the face—dwelt two old bachelor farmers, rejoicing in the name of Smith—Christian names John and James respectively. They being twin-brothers, as a natural consequence they were both the same age, some seventy odd years. In appearance they (I say ‘they’ advisedly, for they were so much alike it was almost an impossibility to tell them apart) were tall, angular, wiry old fellows, with hard, sharply-defined features. In habits they were equally alike with one exception. James was a total abstainer. John, on the contrary, boasted that he had not gone to bed sober, to use his own expression, for ‘five-and-forty year or more.’ They were both sportsmen to the backbone, each brother riding, if possible, harder than the other; the only advantage one could score against the other as regards horsemanship being that old John (the drunkard) was able to mount his horse of a hunting morning without assistance of any sort or kind, whilst the total abstainer was forced to avail himself of a horseblock previous to getting up. Lastly, they both hated each other like poison.

Many a time and oft did the good clergyman of the parish try and reconcile these two perverse old files, but it was not a bit of use. He even, occasionally, went the length of preaching dead at them. But it was pure waste of breath on his part, for old James invariably slept the sleep of the just all through the sermon; and John, who kept awake out of pure opposition to his brother, as he listened to the parson’s well-meant and earnest exhortations with regard to forgiveness generally, would shake his head, purse his lip, and, with a frown at the sleeping sinner in the opposite pew, mutter audibly, ‘No, no, I’m not a-goin’ to do that. No! no!’

Some wag years ago had christened the pair the Corsican Brothers, partly in consequence of their being so much alike, and partly in playful allusion to the strong language each was accustomed to the use on all possible occasions. The hardest swearer in that celebrated army of ours in Flanders would have had his work cut out for him with a vengeance had he entered the list in a cussing match against either of the twins. They were aware of the sobriquet that they went by, and on one occasion old John, riding home from hunting with that lively Oxonian, young Charles Lightfoot, accosted that gentleman point-blank with,—

‘Ar say, Muster Charles; tell us now, what do they mean when they calls me and the silly old fule that disgraces mar name, the Carsican Brothers?’

‘Why do they call you the Corsican Brothers? What! don’t you know?’ replied, in apparent astonishment, the volatile Charles, with a grin. ‘Why, because you’re both so deed ugly to be sure. Ha! ha! ha!’

And, as ‘Muster Charles,’ as he called him, was always full of his chaff, the old farmer, who rather fancied his own personal appearance than otherwise, took Lightfoot’s explanation in an opposite sense, and was henceforth rather pleased than not at the nickname.

In spite then of all persuasions and remonstrances on the part of the Rector and other well-meaning friends, the two old boys still went on hating each other, if possible, harder than ever. They rode against each other out hunting, they bid against each other at cattle sales,—nothing pleased Silkey, the local Tattersall, better than to see the Corsican Brothers scowling at each other from opposite sides of the ring at one of his monthly auctions in Slopperton Market Place, for, as he very well knew, if he could only persuade the ancient Jimmy to make a bid for a heifer or a pig or a sheep, as the case might be, old Jackey, as they called John Smith, who on these occasions was generally pretty full of brandy-and-water, would never rest until he outbid his more temperate brother—until at last the would-be peacemakers gave it up as a bad job, and, to use a slang expression, determined to allow the old reprobates to run loose for the future.

At length, when everybody had long since made up their minds that the Corsican Brothers would make their inevitable descent into what Mrs. Gamp would call the ‘Walley of the Shadder’ without making up their differences, chance brought about the very end that they had for so long been endeavouring to bring about, viz., a reconciliation. It came about in this wise.

The shining light of that particular part of the country in which dwelt the renowned Corsican Brothers was young Lord Hopscotch. Hoppy, as his intimate friends called him, was a great card amongst the sporting fraternity of those parts. All sorts of sports and pastimes he had patronised in his time—hunting, racing, yachting, pigeon-shooting, coaching, cricket, the ring—he had had ‘a go at ’em all,’ he pleasantly would say; and now, having arrived at years of discretion, and being besides rather a flighty-dispositioned young nobleman—one of the

‘All things by turn, and nothing long,’

sort—he had sickened of them all with the exception of the legitimate field-sports of a country gentleman, and had now, to the great delight of his family, taken unto himself a wife, established himself as M. F. H., and, in fact, settled down to his duties as a county magnate in a becoming matter.

Amongst other amusements that my lord had gone in for was one that we have not mentioned in our list, as it could hardly be classed with sport, and that was, breeding fancy stock. Disgusted at the death, a week after he had bought him at Lord Fallowfield’s great sale of shorthorns, of a promising young bull with a pedigree as long as his arm—a mint of money he cost him too, almost as much as would buy a Derby winner—he determined to clear off the whole of his fancy stock—bulls, cows, calves, heifers,—the whole lot, in fact. If the truth must be told too, he was rather glad of the excuse than not, for, never having taken very kindly to farming operations, he began to find the hunting up of pedigrees, the perusal of his stock-book, and the long interviews with his snuff-taking, long-winded Scotch bailiff, Donald McPherson—or, McPhairson, as he himself pronounced it—rather wearisome work, and the death of the young bull having thoroughly disgusted him with the whole business, he forthwith wrote off to Mr. Silkey, the auctioneer, instructing him to arrange for a clearance sale at an early date. And Silkey, having driven over instanter and made a list in the great red-backed, brass-clasped volume he dignified by the name of notebook, of all the valuable cattle—Tenth Duke of Draggletail, Lady Louisa the Second, and so on—there shortly appeared in the county paper, and all the sporting journals, the announcement, headed, ‘Important Sale of Shorthorns,’ of the fact that on such and such a date Mr. Silkey had been honoured by the Right Honourable the Earl of Hopscotch with instructions to sell, without reserve, his lordship’s entire stock of valuable shorthorns. ‘Breeders and connoisseurs,’ wound up the veracious Silkey, ‘will recognise in this list of shorthorns some of the very finest blood in the kingdom; most of them having been selected at different times by his lordship with very great discrimination, and purchased by him quite regardless of expense.’

The day arrived on which the great sale of Lord Hopscotch’s shorthorns was to take place, and half the county were apparently assembled in his lordship’s park, as, with wine-flushed face, the great Mr. Silkey, swelling with importance, pushed his way with difficulty through the crowd and mounted his rostrum. Lord Hopscotch, well alive to the undeniable fact that the true way to a man’s heart, and consequently his purse, is by way of his stomach, had taken good care to provide a sumptuous luncheon, with oceans of champagne, for all comers, in a huge marquee hard by the ring; consequently, when Mr. Silkey, having set the ball a rolling with a few of the pleasantries for which he was so famous, ordered that fine young bull, Tenth Duke of Draggletail, to be led up to the rostrum, ‘the bidding, thanks to the pop,’ as Lord Hoppy, who sat by the auctioneer’s side smoking a huge cigar, facetiously remarked, ‘quickly became fast and furious.’

* * * * * *

‘Now then! wot’s all that noise about? Can’t you keep quiet there? ’Ow is it possible to sell his lordship’s beasts with sich a row as you’re making, going on, I should like to know? What’s that you say, Mr. Smith? I knocked that last cow down to your brother instead of to you? Well, wot of it? with the pair on you as like as two peas, how the deuce am I to tell which of you it is? Which of you am I to put it down to? for, dash me, if I know which is which.’ Thus delivered himself, the eloquent Mr. Silkey, red in the face with indignation and talking, addressing himself more particularly to our friends the old Corsican Brothers, the cause of all the hubbub and confusion in the ring just beneath the rostrum.

The two brothers, standing in close proximity to one another, had both bid for a cow. As usual, old Jackey, well primed with champagne, had outstayed his brother and secured the cow, as he thought. Unfortunately, the auctioneer, not knowing t’other from which, had booked the animal to old Jimmy—a very pardonable error on his part—and a pretty kettle of fish was the result. Old Jimmy, delighted at the mistake, and for once not minding the extra fiver, insisted on sticking to his bargain. Old Jacky, needless to say, was furious; swearing; gesticulating, and going on, until, as the auctioneer told him, he ought to be ashamed of himself at his time of life.

At last, the long-suffering Mr. Silkey could stand it no longer, and, descending from the rostrum, pushed his way through the noisy crowd to where the two disputants were engaged in wordy war.

‘Look here, you two,’ said the indignant auctioneer; ‘I can’t and won’t stand this noise no longer. I shan’t get through my work all day at this rate. If you can’t agree, why don’t you go and fight it out like men? not stand squabbling here like a couple of old washer-women interrupting his Lordship’s sale.’

‘Yes, fight it out! Fight it out!’ yelled the laughing crowd, delighted at the idea.

No sooner said than done. The auctioneer little knew his men when he proposed in a moment of thoughtlessness an ordeal by battle.

The words were scarcely out of his mouth when old Jacky tearing off his coat, and dashing his hat on the ground with such force as to knock the crown clean out, put himself in fighting attitude, and with many oaths called on Jimmy to ‘Come on!’

Nothing loth, brother James divested himself in like manner of his hat and coat, and put himself in position likewise.

The gratified crowd formed a ring in less time than it takes to write this, and in another minute there would indeed have been a set-to between the renowned Corsican Brothers. But it was not to be. Lord Hopscotch, from his seat on the rostrum, who had up to now been an amused spectator, at this juncture thought it high time to interfere, like the good-hearted fellow he was. Accordingly, jumping down from his seat, he was quickly in the ring, and got between the two old pugilists just as they were putting up their hands to fight.

‘Come! Come! This won’t do, you know!’ said the good-natured nobleman, addressing his two turbulent tenants. ‘John and James, I’m ashamed of you! Old gentlemen at your time of life ought to know better. Why you’re no better than a couple of school-boys. Now, look here,’ said Lord Hoppy, ‘we’ll settle this business about the cow in a brace of shakes. We’ll toss. That’s fair for both of you. I’ll chuck up the coin, and our worthy friend Silkey here shall cry. You agree? Good! Now, Mr. Silkey, heads for Jacky, tails for Jemmy. Sudden death! Up she goes!’ And suiting the action to the word his Lordship spun half-a-crown in the air, and dexterously caught it as it fell.

‘Heads!’ shouted the auctioneer.

‘Heads it is!’ replied my Lord, opening his hand. ‘Your cow, Jacky, and I wish you luck with her. And, now, I tell you what it is. You wanted just now to see which was the best man. Now, I’ll tell you a better plan than settling the question with your fists. You shall ride a match across country, this day fortnight. Three miles, say, over a fair hunting country, thirteen stone each, the stakes a hundred a-side, and I’ll give a silver cup to the winner. How will that suit you? Don’t both speak at once.’

‘I’ll hev it for one, my Lordship; and I’ll name mar old brown hoss, Ploughboy. He’ll beat any rubbish he’s got in his stable, I reckon!’ replied old Jacky, with a scornful look at his brother.

‘And I’ll hev it likewise. I’ll name mar grey mare, Starlight Bess. And ’arl bet un a twenty-pun note besides—and put it down now—ar licks him; and holler tew!’ said old Jimmy, producing, as he spoke, a dirty old bag, full of notes and gold, from his breeches-pocket, and picking out a twenty-pound note.

‘Then that’s settled!’ said cheery Lord Hopscotch. ‘This day fortnight, you recollect. Two o’clock. Start and finish to be on my home-farm. You must all come, do you hear, and see which is the best man,’ said he to the farmers standing round. ‘And we’ll have a regular day of it; and I tell you what,’ he added, ‘I’ll bet any of you six to four no one names the winner!’

And, amidst a hearty round of cheers from the assembled company, his popular Lordship skipped gaily once more up into his place on the rostrum next the auctioneer, and, having lit a fresh cigar, bade that worthy once more, ‘Fire away!’

* * * * * *

Drags, carriages, dog-carts, gigs, pony-traps, sportsmen on horseback, sportsman on foot, neatly-habited ladies cantering gaily about, farm-labourers and their wives: such a gathering of country folk are gathered together in the twenty-acre grass-field adjoining Lord Hopscotch’s home-farm as surely never was seen on that spot before. The pigs and the cows, and the cocks and the hens, driven from their favourite lounge by the sudden influx of visitors, to take refuge in the big straw-yard, might well stare with astonishment.

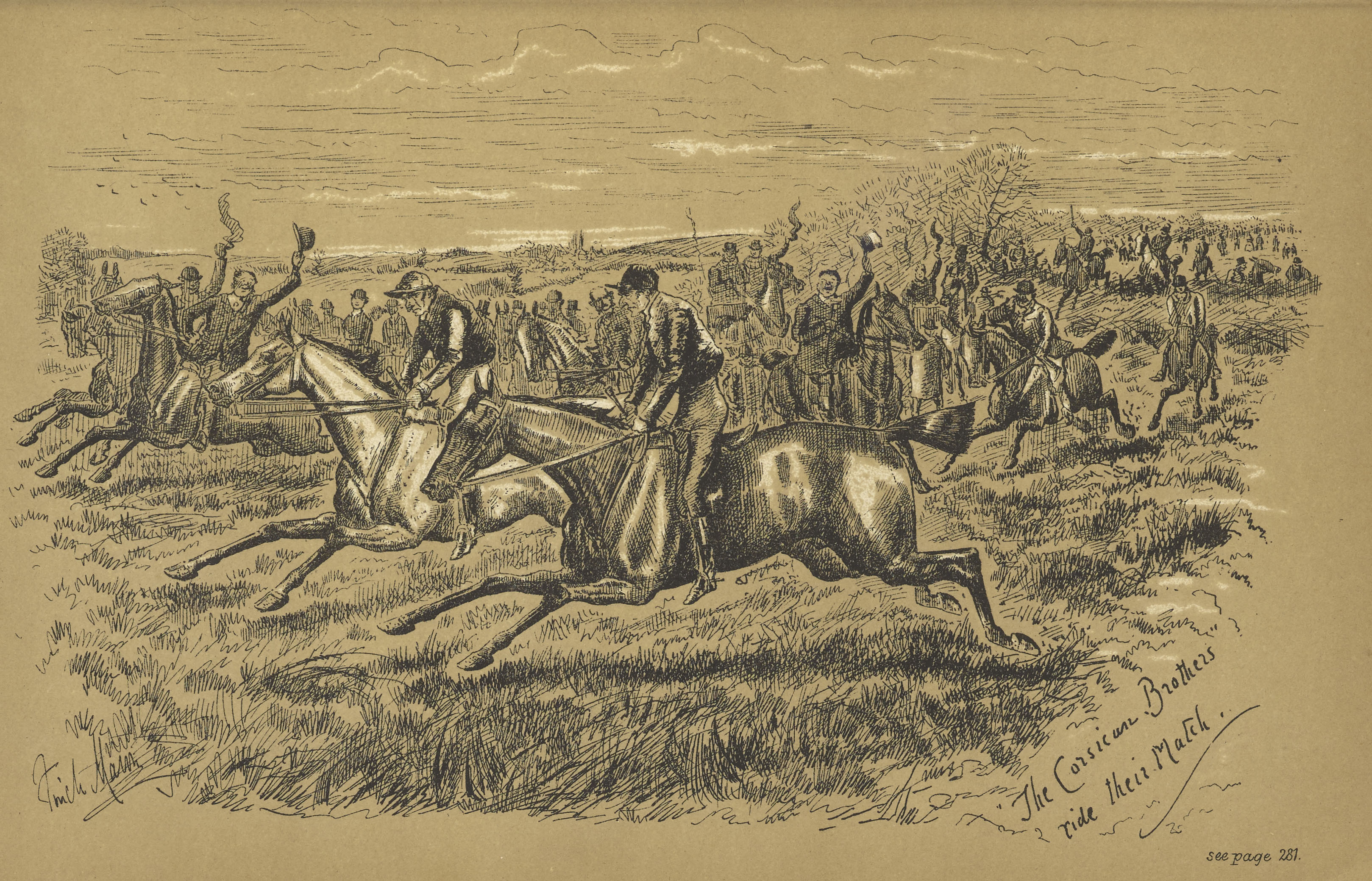

And with what object are all these people here for this bleak, wintry-looking day? Why, to see the old Corsican Brothers ride their great match for a hundred pounds and my Lord’s cup, to be sure!

Old Harry Oldaker, the octogenarian, declares, as he looks round on the assembled multitude, that never in his remembrance has any event caused such excitement in the county as the present match, since the eventful day, more than half a century ago, when Tom the Tinker fought Black Sambo for two hundred a-side on a stage erected for the occasion on Ledbury racecourse. The old man’s heart warms at the sight.

The arrangements are, of course, primitive. The barn belonging to the farm being turned into a weighing-room, whilst the judge’s chair is not discernible to the naked eye, though a long pole with a blue flag attached does duty for the winning-post.

Lord Hopscotch’s huntsman and whips, though, keep the course, and give a business-like air to the surroundings; whilst a huge marquee in the rear points to the fact that ‘Hoppy’ is doing things in his usual freehanded fashion for the benefit of ‘the gentlemen in the top-boots,’ as Thackeray calls the farmers in one of his books—Pendennis, if we recollect rightly. Well may these worthies, as they and their missuses drink my Lord’s health in all manner of liquors, from champagne to hot punch, that cold day, avow that he’s a jolly good fellow, and no mistake at all about it!

Lord Hopscotch, assisted by his huntsman, had himself marked out the course; and, being used to this sort of thing, had done his work admirably. About three and a half miles of fair hunting country (the fences, including some double posts and rails, and a natural brook) had been flagged out. They were to start at a corner of the big grass meadow within sight of everybody, and, running a sort of circle, were eventually to come round to the same field, where they were to finish.

And now let us follow Lord Hopscotch, who is getting on his pony to lead the two old boys to the starting-post. A crowd approaching from the far-end of the field, with two mounted men in the midst, denotes that the jockeys are up, and ready for the fray; and just as my Lord reaches the starting-place the Corsican Brothers ride gallantly up. Very business-like they look too. Old Jacky, who is apparently on capital terms with himself, and loudly offering to back his chance for any amount, is very smart in a sky-blue jacket and black cap, lent him by Mr. Snaffle, the trainer for the occasion. His nether limbs are not, however, so well got up, the brown cord breeches and brown tops he sports, though workmanlike, not harmonising well with the bright jacket.

Old Jimmy is really the smartest of the two, for young William Bacon, the steeplechasing young farmer, of Appletree Farm, has lent him a brand-new emerald jacket with yellow sleeves, and cap to match, lately made for him by his sweetheart, pretty Polly Hopkins. White cord breeches and brown-topped boots complete the bold Jimmy’s attire.

Like their two jockeys, the quadrupeds are a pair of real old uns. Both are well known in the hunt, and both equally clever—in fact, perfect hunters in every way. There is not a place in the country either of them wouldn’t creep through, if they couldn’t jump it.

Perhaps, of the pair, old Jacky’s brown horse, Ploughboy, has most admirers. Ploughboy is as old-fashioned a looking nag as you’d meet in a day’s march—goose-rumped, square-tailed, Roman-nosed, and shoulders such as it does one’s heart good to look at. If any—as no doubt they do—of the readers of Fores’s Notes and Sketches know the old engraving of John Warde on Blue Ruin, with his favourite hound Betsy, and look at Blue Ruin, they will know to a nicety what sort of looking animal Ploughboy was.

‘Now, then, Jack and Jimmy,’ said my Lord, ‘time’s up! Are you both ready?’

‘Bide a minute, my Lordship!’ rejoined Jacky. ‘Do any moor o’ you dommed fules want my ten to won?’ bawled he, for the benefit of the grinning crowd round. ‘What, no moor on yer got the courage to back yeer foolish opinions?’ added he, contemptuously. ‘Then ’arm reddy, my Lordship.’ he said, with a grin, settling himself into his saddle as he spoke, and taking hold of his mare’s head, having previously wetted the palms of his hands, to get a good grip.

‘Ready, Jimmy?’ cried my Lord to the other twin. Jimmy, with a knowing grin, nodded his old head in assent. ‘Then, off you go!’ and, followed by a crowd of mounted followers, some in front, some behind, away went the pair!

‘Well, I’ll be hanged if ever I saw such a game in my life!’ ejaculated my Lord, eyeing the cavalry as they topped the first fence en masse, Jimmy and Jacky in the middle, their excited friends encouraging them with their shouts and yells as they went. ‘I wish I wasn’t judge!’ added he. ‘I’d have ridden with them too.’ He then galloped off to the winning-post, to wait the finish.

The race needs no description. Suffice it to say, that though the pace was a trifle slower than Grand National form; the horse and the mare took their fences without a single mistake, and that when the mob of horsemen showed in sight people in the winning field saw that the Corsican Brothers were both together, and that to all appearance it was anybody’s race.

Indeed it was! As the pair topped the last fence into the winning field they were level with each other. ‘Go it, Jack! Flog away, Jimmy! You’ll win! Jacky’s won! No, he hasn’t! Jimmy’s won, I tell ’ee!’ Such were the cries that rent the air as the pair, flogging and spurring away like demons, passed the judge’s impromptu chair.

‘Who’s won, my Lord?’ was then the cry.

‘I can’t separate ’em! It’s a dead heat,’ shouted his Lordship, almost as excited as the crowd.

‘A dead heat! Hooray!’ yelled the excited mob.

‘One’s as good a man as t’other, and neither’s won,’ shouted one red-faced farmer.

‘Dash mar buttons, but ar always said as old Jimmy was as good a man as Jacky any day,’ vociferated another.

And now little more remains to be told. Suffice it to say, that at the end of the luncheon Lord Hopscotch—after the health of the dead-heaters had been drunk with three times three, and one cheer more—insisted on the Corsican Brothers shaking hands and making friends that very moment. He would take no denial, he said.

And we are delighted to add that his good-natured Lordship’s appeal to their better feelings was not in vain.

Amidst vociferous cheers from the company present, the two old boys, who were seated, one on each side of their host, stood bravely up, and then and there shook hands.

And as they did so, Jacky said to Jimmy, amidst roars of laughter,

‘It’s mar opinion, Jimmy, that you’re a dommed good feller!’

Said Jimmy to Jacky, ‘You’re another!’

Word Count: 3920

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Finch Mason. “The Corsican Brothers.” Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches; a Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British and Foreign Sport, vol. 2, no. 4, 1885, pp. 273-82. Edited by Ben Wilson. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 10 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-corsican-brothers/.

Editors

Ben Wilson

Chelsea Holdaway

Posted

5 October 2016

Last modified

10 March 2026