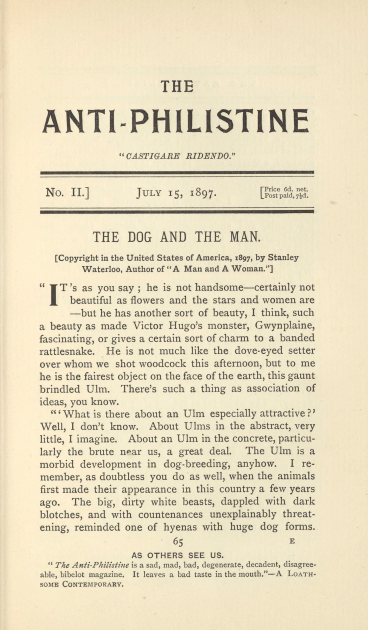

The Dog and the Man

The Anti-Philistine: A Monthly Magazine & Review of Belles-Lettres: Also a Periodical of Protest, vol. 1, issue 2 (1897)

Pages 65-73

Introductory Note: “The Dog and the Man” is a striking gothic story told as a dramatic monologue. The narrator is in conversation with a friend and confidant. Prefaced by his peculiar attachment to a vicious dog and a rocky friendship with “the Man,” the narrator relates the tale of betrayal, intrigue, and retaliation that led him to his current isolation. The tale engages the reader through an eerie mix of obsession with death and dynamic storytelling.

“It’s as you say; he is not handsome—certainly not beautiful as flowers and the stars and women are—but he has another sort of beauty, I think, such a beauty as made Victor Hugo’s monster, Gwynplaine, fascinating, or gives a certain sort of charm to a banded rattlesnake. He is not much like the dove-eyed setter over whom we shot woodcock this afternoon, but to me he is the fairest object on the face of the earth, this gaunt brindled Ulm. There’s such a thing as association of ideas, you know.

“‘What is there about an Ulm especially attractive?’ Well, I don’t know. About Ulms in the abstract, very little, I imagine. About an Ulm in the concrete, particularly the brute near us, a great deal. The Ulm is a morbid development in dog-breeding, anyhow. I remember, as doubtless you do as well, when the animals first made their appearance in this country a few years ago. The big, dirty white beasts, dappled with dark blotches, and with countenances unexplainably threatening, reminded one of hyenas with huge dog forms. Germans brought them over first, and they were affected by saloon-keepers and their class. They called them Siberian bloodhounds then, but the dog fanciers got hold of them, and they became, with their sinister obtrusiveness, a feature of the shows; the breed was defined more clearly, and now they are known as Great Danes or Ulms, indifferently. How they originated I never cared to learn. I imagine it sometimes. I fancy some jilted, crabbed descendant of the sea-rovers retiring to his castle, and endeavouring, by mating some ugly bloodhound bitch with a wild wolf, to produce a quadruped as fierce and cowardly and treacherous as man or woman may be. He succeeded only partially, but he did well.

“‘Never mind about the dog,’ and tell you why I’ve been gentleman farmer, sportsman, and half-hermit here for the last five years—leaving everything just as I was getting a grip on reputation in town, leaving a pretty wife too, after only a year of marriage? I can hardly do that; that is, I can hardly drop the dog, because, you see, he’s part of the story. Hamlet would be left out decidedly were I to read this play without him. Besides, I’ve never told the story to anyone. I’ll do it, though, to-day. The whim takes me. Surely a fellow may enjoy the luxury of being recklessly confidential once in half a decade or so, especially with an old friend, and a trusted one. No need for going far back with the legend. You know it all up to the time I was married. You dined with me once or twice later.

“You remember my wife? Certainly, she was a pretty woman; well bred too, and wise, in a woman’s way. I’ve seen a good deal of the world, but I don’t know that I ever saw a more tactful entertainer or, in private, a more adorable woman, when she chose to be affectionate. I was in that fool’s paradise which is so big, and holds so many people sometimes for a year and a half after marriage. Then, one day, I found myself outside the wall.

“There was a beautiful set to my wife’s chin, you may recollect—a trifle strong for a woman, but I used to say to myself that, as students know, the mother most impresses the male offspring, and that my sons would be men of will. There was a fulness to her lips. Well, so there is to mine. There was a delicious, languorous craft in the look of her eyes at times. I cared not at all for that. I thought she loved me, and knew me. Love of me would give all faithfulness; knowledge of me, even were the inclination to wrong existent, would beget a dread of consequences. My dear boy, we don’t know women. Sometimes women don’t know men. She did not know me any more than she loved me. She has become better informed.

“‘What happened?’ Well, now came in the dog and the man. The dog was given me by a friend who was dog mad, and who said to me the puppy would develop into a marvel of his kind, so long a pedigree he had. I relegated the puppy to the servants and the basement, and forgot him. The man came in the form of an accidental new friend, an old friend of my wife, as subsequently developed. I invited him to my house, and he came often. I liked to have him there. I wanted to go to Congress—you know all about that—and wasn’t often at home in the evening. He made the evenings less lonely for my wife, and I was glad of it. I told her I would make amends for my absence when the campaign was over. She was all patience and sweetness.

“Meanwhile, that brute of a puppy in the basement had been developing. He had grown into a great rangy, long-toothed monster, with a leer on his dull face, and the servants were afraid of him. I became interested, and made a pet of the uncouth animal. I studied the Ulm character. I learned queer things about him. Despite his size and strength, he was frequently overcome by other dogs when he wandered into the street. He was tame until the shadows began to gather as the sun went down. Then a change came upon him. He ranged about the basement, and none but I durst venture down there. He was, in sort, a cur by day; at night, a demon. I suppose the early dogs of this breed were trained to night slaughter and savageness alone, and that it was a case of atavism, a recurrence of hereditary instinct. It interested me vastly, and I resolved to make him the most perfect of watch-dogs. I trained him to lie couchant, and to spring upon and tear a stuffed figure I would bring into the basement. I noticed he always sprang at the throat. ‘Hard lines,’ thought I, ‘for the burglar who may venture here!’

“It was a little later than this nonsense with the dog, which was a piece of boyishness, a degree of relaxation to the strain of my fight with the down-town conditions, that there came in what makes a man think the affairs of his world are not adjusted rightly, and makes recurrent the impulse which was first unfortunate for Abel—no doubt worse for Cain. There is no need for going into details of the story, how I learned, or when. My knowledge was all-sufficient and absolute. My wife and my friend were sinning, riotously and fully, but discreetly, sinning against all laws of right and honour, and against me. The mechanism of it was simple. The grounds behind my house, you know, were large, and you may not have forgotten the lane of tall clipped shrubbery that led up from the rear to a pretty summer-house. His calls in the evening were made early, and ended early. The pinkness of all propriety was about them. The servants suspected nothing. But, his call ended, the graceful gentleman, friend of mine and lover of my wife, would walk but a few hundred paces, then turn, and enter my grounds at the rear gate I have mentioned, and pass up the arbour to the pretty summer-house. He would find time for pleasant anticipation there, as he lolled upon one of the soft divans with which I had furnished the charming place, but his waiting would not be long. She would soon come to him, and time passed swiftly.

“That is the prologue to my little play. Pretty prologue, isn’t it, but commonplace? The play proper isn’t! The same conditions affect men differently. When I learned what I have told—after the first awful five minutes—I don’t like to think of them even now—I became the most deliberate man on the face of this earth peopled with sinners. Sometimes, they say, the whole substance of a man’s blood may be changed in a second by chemical action. My blood was changed, I think. The poison had transmuted it. There was a leaden sluggishness, but my head was clear.

“I had odd fancies. I remember I thought of a nobleman who had another torn slowly apart by horses, for proving false to him at the siege of Calais. His cruelty had been a youthful horror to me. Now I had a tremendous appreciation of the man. ‘Good fellow, good fellow!’ I went about uttering to myself in a foolish, involuntary way. I wondered how my wife’s lover could endure the strain of four strong Clydesdales, each started at the same moment—one north, one south, one east, one west. His charming personal appearance recurred to me, and I thought of his fine neck. Women like a fine-throated man, and he was one. I wondered if my wife’s fancy tended the same way. It was well this idea came to me, for it gave me an inspiration. I thought of the dog!

“There is no harm, is there, in training a dog to pull down a stuffed figure? There is no harm either, if the stuffed figure be given habiliments resembling those of some friend of yours? And what harm can there be in training the dog in a garden arbour instead of a basement? I dropped into the way of being at home a little more. I told my wife she should have alternate nights at least, and she was grateful and delighted. And, on the nights when I was at home, I would spend half-an-hour in the grounds with the dog, saying I was training him in new things, and no one paid attention. I taught him to crouch in the little lane, close to the summer house, and to rush down and leap upon the manikin when I displayed it at the other end. God in heaven! how he learned to tear it down and tear its imitation throat! The training over, I would lock him up in the basement as usual. But, one night, a despatch came summoning me to another city. The other man was to call that evening, and he came. I left before nine o’clock, but just before going I released the dog. He darted for his post in the garden, and, with gleaming eyes, crouched as he had been accustomed to do, watching the entrance to the arbour.

“I can always sleep well on a train. I suppose the regular sequence of sounds, the rhythmic throb of the motion has something to do with it. I slept well, the night of which I am telling, and awoke refreshed when I reached the city of my destination. I was driven to a hotel, I took a bath; I did what I rarely do, I drank a cocktail before breakfast, but I wanted to be luxurious. I sat down at the table. I gave my order, and then lazily opened the morning paper. One of the despatches deeply interested me.

“‘Inexplicable Tragedy’ was the headline. By the way, ‘Inexplicable Tragedy’ has just about the number of letters to fill a column neatly in the style of ‘heading’ now the fashion. I don’t know about such things, but it seems to me compact and neat, and most effective. The lines which followed gave a skeleton of the story:

‘A WELL-KNOWN GENTLEMAN KILLED BY A DOG.’

‘THEORY OF THE CASE WHICH APPEARS THE ONLY ONE POSSIBLE UNDER THE CIRCUMSTANCES.’

I read the despatch at length. A man is naturally interested in the news from his own city. It told how ‘a popular club man had been found in the early morning lying dead in the grounds of a friend, his throat torn open by a huge dog, an Ulm, belonging to that friend, which had somehow escaped from the basement of the house where it was ordinarily confined. The gentleman had been a caller at the house the same evening, and had left at a comparatively early hour. Some time later the mistress of the place had gone out to a summer-house in the grounds to see if the servants had brought in certain things used at luncheon there during the day, but had seen nothing save the dog, which snarled at her, when she had gone into the house again. In the morning the gardener had found the body of Mr. ––– lying near an arbour leading from the gate-way to the summer-house. It was supposed that the unfortunate gentleman had forgotten something, a message or something of that sort, and upon its recurrence to him had taken the shortest cut to reach the house again, as he might do, naturally, being an intimate friend of the family.’ That was all there was of the despatch.

“Oddly enough, I received no telegram from my wife; but, under the circumstances, I could do nothing else than return to my home at once. I sought my wife, to whom I expressed my horror and my sorrow, but she said very little. The dog I found in the basement, and he seemed very glad to see me. It has always been a source of regret to me that dogs cannot talk. I see that someone claims to have learned that monkeys have a language, and that he can converse with them, after a fashion. If we could but talk with dogs!

“I saw the body, of course. I asked a famous surgeon once which would kill a man the quicker, severance of the carotid artery or the jugular vein? I forget what his answer was, but in this case it was immaterial. The dog had torn both open. It was on the left side. From this I infer that the Great Dane sprang from the right and that it was that big fang in his left upper jaw that did the work. (Come here, you brute, and let me open your mouth.) There, you see, as I turn his lips back, what a beauty of a tooth it is! I’ve thought of having that particular fang pulled and of having it mounted and wearing it as a charm on my watch chain, but the dog is likely to die long before I do, and I’ve concluded to wait till then. It’s a beautiful tooth!

“I’ve mentioned, I believe that my wife was a woman of keen perception. You will understand that, after the unfortunate affair in the garden, our relations were somewhat—I don’t know just what word to use, but we’ll say ‘quaint.’ It’s a pretty little word, and sounds grotesque in this conversation. One day I provided an allowance for her, a good one, and came here alone to play farmer, and shoot, and fish, for four or five years. Somehow, I lost interest in things, and knew I needed a rest. As for her, she left the house very soon and went to her own home. Oddly enough, she is in love with me now—in earnest this time. But we shall not live together again. I could never eat a peach off which the street vendors had rubbed the bloom. I never bought goods sold after a fire, even though externally untouched. I don’t believe much in salvage as applied to the relations of men and women. I’ve seen, in the early morning, the unfortunates who eat choice bits from the garbage barrels. So they stifle a hunger, but I couldn’t do it, you know. You’ve heard about all. Odd, isn’t it, what little things will disturb the tenor of a man’s existence and interfere with all his plans?

“I came here and brought the dog with me. I’m fond of him, despite the failings in his character. Notwithstanding the currishness by day, and the ferocity which comes out with the night, there is something definite about him. You know what to expect and what to rely upon. He does something! That is why I like an Ulm.

“What am I going to do? Why, come back to town next year and pick up the threads. My nerves, which seemed a little out of the way, are better than they were when I came here. There’s nothing else to equal country air. I must have that whirl in my electoral district yet. I don’t think the boys have quite forgotten me. Have you noticed the drift at all? I could only judge from the newspapers. How are political matters in the Ninth Ward?”

Audiobook Format

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Stanley Waterloo. “The Dog and the Man.” The Anti-Philistine: A Monthly Magazine & Review of Belles-Lettres: Also a Periodical of Protest, vol. 1, no. 2, 1897, pp. 65-73. Edited by Maddox Maddox. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 22 October 2024, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-dog-and-the-man/.

Editors

Maddox Maddox

Alayna Een

Isaac Robertson

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Danny Daw

Posted

5 June 2020

Last modified

20 October 2024