The End of the Tragedy

The Argosy, vol. 50, issue 3 (1890)

Pages 164-176

Introductory Note: This mystery tale explores how a privileged Victorian household is upturned by the suspicious death of one of its own. Blair Royden is invited by his old friend William Seagrave to visit the Seagrave’s estate. What Blair doesn’t know is that Seagrave’s young stepson has recently been killed, and the mystery of his murder is still unsolved. As a doctor and an educated man, Blair observes the suspicious and erratic behavior of those around him, and his discoveries lead him to the key to a mystery that is far more disturbing than he anticipated.

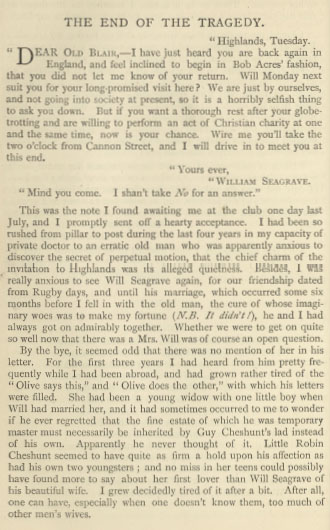

“Highlands, Tuesday.

“Dear Old Blair,—I have just heard you are back again in England, and feel inclined to begin in Bob Acres’ fashion, that you did not let me know of your return. Will Monday next suit you for your long-promised visit here? We are just by ourselves, and not going into society at present, so it is a horribly selfish thing to ask you down. But if you want a thorough rest after your globe-trotting and are willing to perform an act of Christian charity at one and the same time, now is your chance. Wire me you’ll take the two o’ clock from Cannon Street, and I will drive in to meet you at this end.

“Yours ever,

William Seagrave.

“Mind you come. I shan’t take No for an answer.”

This was the note I found awaiting me at the club one day last July, and I promptly sent off a hearty acceptance. I had been so rushed from pillar to post during the last four years in my capacity of private doctor to an erratic old man who was apparently anxious to discover the secret of perpetual motion, that the chief charm of the invitation to Highlands was its alleged quietness. Besides, I was really anxious to see Will Seagrave again, for our friendship dated from Rugby days, and until his marriage, which occurred some six months before I fell in with the old man, the cure of whose imaginary woes was to make my fortune (N.B. It didn’t!), he and I had always got on admirably together. Whether we were to get on quite so well now that there was a Mrs. Will was of course an open question.

By the bye, it seemed odd that there was no mention of her in his letter. For the first three years I had heard from him pretty frequently while I had been abroad, and had grown rather tired of the “Olive says this,” and “Olive does the other,” with which his letters were filled. She had been a young widow with one little boy when Will had married her, and it had sometimes occurred to me to wonder if he ever regretted that the fine estate of which he was temporary master must necessarily be inherited by Guy Cheshunt’s lad instead of his own. Apparently he never thought of it. Little Robin Cheshunt seemed to have quite as firm a hold upon his affection as had his own two youngsters; and no miss in her teens could possibly have found more to say about her first lover than Will Seagrave of his beautiful wife. I grew decidedly tired of it after a bit. After all, one can have, especially when one doesn’t know them, too much of other men’s wives.

“She might as well have sent me a message, or Will might have invented it for her,” I thought, for, for a man, he was rather unusually strong in little politenesses of that sort. “I suppose there has been a death in the family, if they are not going out much at present. Wonder who it is!”

Three days later I and my traps were deposited at the country station where Will Seagrave was to have met me, but by some mis chance he had not arrived. Having a righteous horror of country flys, and remembering Will’s unpunctuality of old, I determined to wait where I was until either he or a messenger from Highlands should put in an appearance. I had just lighted my second cigarette when a couple of men came out of the station hotel, by the doorway of which I was lounging, and having nothing better to do, I stood listening to what they were saying. They were apparently local tradesmen who had been having a heated argument over their pipes, and each was unwilling to leave the other unconvinced.

“I tell you,” said one, striking his hands together impatiently—“I tell you it is pure nonsense. It don’t stand to no manner of reason. It is four months now since that poor little chap was killed, and don’t you think that if he’d been shot by a passing tramp as you may say, why, that it would have come out long before now?”

“That’s true enough,” said the elder man more mildly, “but who says it hasn’t come out? I says now as I said at the inquest, that it was Jake Ilford. Everyone for miles round knew that there was bad feeling between Mr. Seagrave and him. Everyone knew that it was through Mr. Seagrave he was clapped in gaol, and that he swore to do him a nasty turn when he could.”

“So he did, so he did,” said the first speaker, as though grudging him the concession, while my cigarette went out unheeded in my puzzled surprise. “But if you mean to explain that by saying that Jake Ilford comes out of prison, and creeps along to Highlands that March night, and takes and shoots down Master Robin from behind a hedge like as he would a rabbit, and then goes on his way all unconcerned like—why then I say again it don’t stand to no manner of reason.”

“It stands more to reason than to say a bit of a child like that shot hisself,” said his companion, testily, “and hasn’t Ilford been missing ever since?”

Here a friend hailed them from the other side of the road, and they went away from the hotel, and out of earshot.

Left to myself, I turned back into the station, and paced the platform in the direst perplexity. Little Robin Cheshunt was killed, shot, as my unconscious informer had said, like a rabbit, and the name of his murderer was still an open question. So much I had gathered from the men’s talk, but they had only said enough to make me intensely anxious to hear more. Who was this Jake Ilford whom gossip accredited with so strong a hatred of the owner of Highlands that the death of the little heir was laid to his charge? How came it that Seagrave, a rich man, had not been able to work the law sufficiently to capture him? And why on earth—my curiosity giving way to a feeling of resentment—why on earth had he asked me down to a grief-stricken house without giving me any inkling of how gloomy would be my visit? At this moment a porter came up and touched his cap.

“Beg pardon, sir, but if you’re the gentleman for Highlands, Mr. Seagrave says would you kindly step this way. He can’t leave the horses.”

Through the open door I saw a pale-faced man, dressed in deep mourning, who was sitting on the box-seat of a phaeton; but it was not until my new guide shouldered my traps and started off in its direction that I realised that the sad-looking man at whom I had been gazing was no other than my old friend. Good heavens, how he had changed! He looked a good ten years older than his thirty-six years, and from a robust man of medium height, he seemed literally to have shrunk in stature until he gave one the idea of having just recovered from a serious illness.

“Have you got those flowers for your mistress? Are they packed safely?” I heard him say to the groom as I came up, and I declare I welcomed the words with relief. Finding he was still full of his wife and her wants seemed a tangible proof that this shadow of his former self was really and truly Seagrave.

“Hullo, Will. You’re a nice sort of fellow to volunteer to meet one.”

His thin face flushed with pleasure as he leaned forward and grasped my hand.

“My watch has just come back from the cleaner’s, and consequently has taken to a habit of stopping. I am awfully sorry to be late,” he said. “Get in. The horses won’t stand.”

Apparently they would not, for I had barely cleared the wheel when they broke into a spirited trot.

“You can’t think how glad I am to see you, Blair,” he went on. “We never go up to town now, and I haven’t seen a friend here for months past.”

“No? You have been in trouble. I have been hearing something about it.”

He jumped at my words as though I had given him an electric shock.

“You have heard about it—where? Did they speak of it at the station?”

In turning to answer him, I caught sight of the groom, who was leaning well forward from the back seat. It was my first good view I had had of him, and while I was answering my friend’s questions, and telling him of the men’s talk at the hotel door, I was all the time cudgelling my brains to remember where on earth I had seen his servant before. My unusually good memory for faces is a pet vanity of mine, and it annoyed me that, though I could have sworn to the hatchet nose and deep-set eyes of the man behind us, I could neither recall his name nor where it was that I had seen him. Finally, I gave it up, and turned my undivided attention to his master.

“Of course it is an intensely painful subject for both of us,” Seagrave was saying; “but I must tell you about it now, because I am particularly anxious you should not speak of it before the wife.”

I muttered something, and nodded comprehendingly. He need not have alarmed himself, I thought; it was hardly a subject one would care to discuss with any mother.1For “subject,” the original reads “subjec.”

“It was in March last,” he went on, still keeping his eyes steadily upon his horses’ ears; “our dear little lad had run out into the garden in the twilight. He was shot. We have never been able to find the man who fired at him.”

Hearing the story like this, wrung reluctantly, as it were, from his lips, the curt recital sounded infinitely more impressive than when eked out by the gestures and comments of the tradespeople, and I felt a sudden rush of very real sympathy.

“You poor old fellow! I am most heartily sorry to hear of this. Who found the poor child?”

“I did.” He shivered as he spoke.

At this moment I again caught a glimpse of the quiet face of the listening groom. The straight-cut lips were curling in a faint smile, and the contrast to the pale, suffering face at my side made me feel positively uncomfortable. Dear old Will tried to turn the conversation into a more cheerful vein by pointing out the various beauties of the drive, but I only answered him in monosyllables. That evil smile haunted me, and for the present, at least, had put ordinary talk out of the question.

As we entered the house, I told Seagrave that it annoyed me not to be able to recollect the name of his groom, as I was certain I had seen him before.

“Perhaps you have,” he said carelessly. “We have only had him a week. He is a Londoner whom my wife was interested in somehow—the brother of a former servant of hers, I fancy. Tom Rutton is his name.”

He turned out of the square hall through one of the many doors which opened upon it, and in another moment I was shaking hands with my hostess.

“Olive, this is Dr. Royden. You have often heard me speak of Blair Royden, my little fag at Rugby,” said Seagrave in oddly persuasive tones, which somehow gave me the impression he had been dubious about my welcome, and then he began hastily unpacking the hamper of flowers we had brought with us from the little town.

While he fussed about the what-nots for specimen vases in which to arrange them, and chatted briskly about his lack of manners in arriving too late for my train, I occupied myself in studying his wife. She was a tall, slight woman, with a quantity of dull fair hair, and a languid, graceful manner of moving. It struck me that under any other circumstances I should mentally have summed her up as singularly beautiful, but there was something about the waxen skin and general inertness which commanded a feeling of awe rather than of admiration. In her heavy pall-like draperies she looked as if all the vitality and spring of youth had gone from her—as if in all but mere actual breath the woman were dead already.

When, with the help of the flowers, we were getting through a rather laboured chit-chat, I caught the sound of unsteady little feet in the hall beyond, and through the open doorway I caught sight of a couple of white-frocked children. Welcoming them as a happy break in a very stiff quarter of an hour, I called out to them, and the elder of the two crept nearer the threshold.

“Is my papa there?” she demanded.

“Yes, and mamma too. Come and make friends.”

The bright little face clouded instantly, and in an almost inaudible whisper she was endeavoring to make me understand that she must not come in unless “papa” were alone, when her mother’s voice cut her short.

“Go away at once, and take Willie with you. You have no business here,” she said, speaking to her little daughter in exactly the same dull, monotonous voice in which she had been speaking to me; and it was pitiful to see the scared expression with which the children trotted away. And this was the wife of whom Will Seagrave had written so proudly!

I felt rather at a loss for words when presently he took me up to my room, and shut the door upon us with an interrogatory “Well?”

His eager, questioning gaze reminded me of the school-days when I, his junior by some years, was first promoted to the post of general adviser and father confessor. I remember that then I used to explain this preference to myself in a way which was by no means unflattering to my self-esteem; but since then I have modified my opinion, and think that as a boy he consulted me for the very same reasons which had now induced him to invite me to Highlands. He felt a characteristic necessity to confide in someone, and I possessed the valuable quality of being able to hold my tongue.

I pretended to misunderstand that “Well?” and flinging up my window to look at the view, I asked: “Well, what?”

“What do you think of my wife? How does she strike you? Do you think she is in bad health?” All his easy brightness had disappeared, and he fronted me with the same harassed expression I had observed at the station. “You are a doctor, Blair. You must know,” he added.

“My dear Will,” I remonstrated, “I have only just seen Mrs. Seagrave. I can’t tell you more than anyone else could tell you. She is evidently suffering from mental depression, and will probably grow stronger and happier as time goes on, and she gets over the shock of her boy’s death.”

“That she never will,” said Seagrave emphatically, and then he abruptly changed the subject. “If you find the house even duller than you expected, promise me that you won’t leave us at all events under the week.”

Now as that was exactly what I was intending to do, I suppose I must have looked somewhat taken aback, for Seagrave at once continued to press the matter so earnestly that in the end I yielded. I felt I should be horribly in the way, but, after all, of that he must be the best judge.

It was as well he had bound me by a promise, or, undoubtedly, on the third day at latest I should have started back to town. The whole atmosphere of the place worried and depressed me, and I felt that my temper was rapidly growing as uncertain as Mrs. Seagrave’s own. Certainly it was anything but a cheerful visit.

Whenever he was with his wife, Seagrave was, to all appearance, enabled to throw off his own troubles, and, with a devotion I have never seen equaled, set himself to the task of wooing her, if not to brighter spirits, at all events to a more resigned state of mind. But when he was alone with me he gave himself up unreservedly to his grief.

I do not think the loss of his little step-son had much to do with it. He was infinitely sorry, of course, but not even his love for his own children counted one feather-weight as compared with his love for his wife. The latter he simply worshiped, and as the days went slowly by, my position in the household was not rendered more comfortable by my growing conviction that she was not worth it. Were all her troubles, her irritability, and periods of intense nervous excitement—were they solely due to little Robin? Seagrave of course said yes, and would spend hours in narrating how blithe and full of life she used to be, how fond of gaieties of all sorts, and yet how devoted a wife and mother. Still I had my own doubts, although naturally I kept them to myself.

It was thinking of Rutton, the groom, which first put the suspicion into my head. The Seagraves’ indoor man had fallen ill, and instead of engaging a new servant, Mrs. Seagrave had insisted upon Rutton filling his place. Consequently, I saw a good deal of him, and it soon became a source of wonderment to me how it was possible for Seagrave to have the man about the house as much as he did, without noticing the very evident understanding which existed between him and his mistress. This was through no fault of Rutton’s, who, though an abominably bad servant, as far as a knowledge of his duties went, was always quietly respectful and apparently unconcerned. But Mrs. Seagrave had by no means so perfect a command of herself. At meals, for instance, she would follow him about with her eyes, until her husband’s blindness became a thing to marvel at; and once when, deceived by a resemblance of doors, I hastily entered her boudoir, it was to find them talking earnestly together. I caught something about “your husband might notice it,” before her exclamation, “I thought the door was locked!” brought my stammered apologies, but the incident certainly served to strengthen my theories.

At the end of the week I was ready to laugh myself to scorn for having jumped to such romantic conclusions, for it was then that it suddenly flashed across me where it was that I had seen the fellow before. This time it was not only possible but imperative to speak to Seagrave about him, and, at the risk of adding to his perplexities, I attacked the subject that very night. It was late, the house was quiet, and we two were in the smoking-room.

“What are you after now?” Seagrave asked curiously, as I stole softly to the one door and glanced right and left in the passage before reclosing and locking it. “You don’t imagine any of the servants are staying out of their beds to listen to our instructive conversation, do you?”

“I like to make sure,” I said equably. “I have something to tell you;” and then I followed his example and proceeded to light up, glancing at him as I did so.

He was looking better to-night, I fancied. For the first time since I had been with him, his wife had somewhat shaken off her lethargy, and had actually taken her share in a newspaper discussion we had had during dinner. As a natural result, Seagrave was looking more like himself again than I had yet seen him, and as he leaned indolently back in his old arm-chair, and puffed away silently at his meerschaum, he looked both quiet and contented.

“What is the important piece of news?” he asked, lazily.

“This. I have set my mind at rest at last. You remember how it bothered me not to be able to recall where I had seen Rutton?”

Seagrave nodded.

“Well, now I know. Soon after I reached London this last time, I went on to call on a man named Drayton—I don’t think you know him. As I was waiting in the drawing-room, my friend passed through the conservatory which joins it, talking to this identical man. He told me afterwards that the fellow had been instrumental in recovering some jewellery for him, and I suppose he had been called that particular morning to receive a douceur of some sort for his pains.”2A douceur is a payment or bribe.

Seagrave stared at me blankly. “Rutton had?” he said, slowly. “My groom?”

“Yes, but don’t you see, Will, he is only shamming as a servant in Mrs.—I mean in someone’s pay! I would swear to his face. Rutton is a detective.”

“A detective?” He started violently forward, gripping the arms of the chair as he did so. His pipe had fallen to the floor, and it lay in atoms at his feet; his face had blanched. We sat staring at each other for a full minute, while a horrible, sickening dread was slowly forcing itself upon me: and then the nervous grip relaxed, and he fell back in his chair, covering his face with his hands. “Good heavens!” he groaned, “it has come at last! She suspects me.”

“That you, you killed her child?”

He must have read the question in my eyes, for but for his labored breathing the silence remained unbroken.

“Yes, it was I who killed him.”

He answered me in the hoarse, unnatural whisper we sometimes hear from the lips of the insane, and then he broke into such terrible weeping as I pray I may never hear again.

Phew! I rose from my seat, and walked to the other end of the long room. I felt an unconquerable impulse to place as much distance as possible between myself and this old friend of mine, who seemed to have grown suddenly so unfamiliar. Why, oh why had he done this thing?

It was only for an instant that this feeling mastered me, for as soon as I could collect my scattered thoughts, it was to blame myself for the momentary disloyalty. It must have been an accident, of course, and the only question that remained was, why he had not at once avowed it. I came back again to my place, and laid my hand upon Seagrave’s shoulder.

“Come, rouse up, old fellow,” I said, speaking as cheerily as I knew how, although, even to my own ears, the attempt sounded rather a failure. “You must tell me all about it. You ought to have told me before.”

He looked up at last, but there was a dazed expression on his face as though he had not fully heard what I had said.

“Do you think Olive knows, or do you think she only suspects?”

“Neither,” I said, stoutly. “She merely feels that sufficient search is not being made for—for the one who did it, and so she is trying on her own account. It is just the stupid sort of thing a woman does do.”

“Then why didn’t she tell me?”

I was posed for a moment, and then I said hurriedly, “Oh, well, you see, the poor little chap wasn’t your own son. Mrs. Seagrave might very well feel that, with the best intentions in the world, your love could not equal hers. She might imagine you would consider it useless to continue the search after four months.”

There was a long pause before he spoke again; evidently he was bracing himself to the confession of that sad day’s work. He began at last, in a hesitating, self-communing sort of way, but after a little his voice grew clearer and he went on more graphically. The plunge once made, it was evidently a relief, as in old boyish days, to take me into his confidence.

“It was in March. A big dog, belonging to one of the farmers about, had annoyed us and frightened the children by continually leaping over the wall which divides us from the lane. And it was then, when I was up in town one day, that I brought a pistol back with me. It was not with any idea of the animal that I got it, but I had had threatening letters from a poacher whom I had once been the means of sending to gaol, and I thought it was as well to have one. These country lanes are lonely at night, and sometimes I am driving late.”

“So you brought it back here with you?” I asked the question after the silence had grown so lengthy that I thought he had forgotten my presence. He roused himself with a start.

“Yes. I got home about five o’clock: it was just getting dusk. Olive was out, paying calls, and she had taken our little Dulcie with her in the carriage. You have seen how she treats the child now, but in those days she idolized her only less than she did Robin. I asked for him, and I was told he was at nursery tea, so I went into the drawing-room to wait for Olive’s return, and seated myself by the open window, on the look-out for the carriage. I was feeling fagged and ill-tempered. The business on which I had been up to town had gone all wrong: I was anxious about Olive, who had a cough, and ought to have been home before dusk; and I was rendered more irritable every moment by the ear-splitting noises which came from the adjoining field. The pupils at the vicarage had erected a sort of amateur shooting gallery there, and were supposed to be practising.”

“Go on, dear old man, go on. And then?”

“Then, as I sat by the open window examining my new purchase, the dog—a surly brute that ought to have been chained—came bounding over our wall. It all happened in a flash. Maddened at the cool disregard of the master who let it wander about loose at its own sweet will, and with a half-thought of how terrible the consequences might be if the huge beast came down like that upon our little ones, I raised my hand and I fired. And then—Oh, Blair”—he caught my hand with a convulsive shudder—“think of the horror of it all! At the same instant that I pulled the trigger, a little white-clad golden-haired child came running between me and the beast at which I was pointing. The sharp angle of the bow-window had hidden him from me, and—and—he died without a struggle or a cry. I tore madly over the grass, and reached our darling. A smile was still resting on the dear face, and as I lifted him in my arms the little dimpled hands fell loosely forward on to my neck as they had clasped me hundreds of times before. I had thought for nothing but his mother, and how to get him safely in the house before she should come back and find him. The dining-room—you have not seen it; we never go into it now—was the nearest to me, and I carried the tiny, motionless figure in through the French window and laid it upon the long table. As I did so, I caught the sound of wheels upon the drive, and I rushed out through the hall to the front door to meet my wife and in some sort prepare her for the shock. The carriage held only Dulcie and her nurse. Her mistress, so the woman told me, had got out half-way up the drive to look at some newly-planted ferns, and had entered the house through the dining-room window.”

“And found the boy?”

My breathless question was simply answered by a grave “Yes.” He had so often lived over again the whole terrible scene that the narration of it had no longer any power to stir him. It was too painful, too horrible, to find vent in mere wordy excitement. Presently he went on speaking:

“When I got back into the room I found her like a mad thing. Holding the child to her and covering him with kisses; then laying him down, chafing the little stiffening hands, or searching wildly for mark or sign of the wound; then again calling on him to speak to her. ‘Look at poor mother, Robin. Darling, speak to mother.’ She turned and clutched me as I ran up to her. ‘He has been shot, Will, he has been shot,’ she said, and then she grew suddenly quiet. She nestled up to me, recoiling from the lad as if in horror, although her eyes were fascinated upon the small round hole above his breast. ‘He is dead,’ she shrieked at last, and then breaking from me she threw herself again upon the child, praying God that she might be helped to avenge him, that He would grant her strength to track down the murderer, and take his life as he had taken her boy’s. Blair, it was fearful.”

He stopped abruptly. Great drops of moisture were upon his forehead, and even his lips were white. To such a man, and loving his wife as passionately as he did, the scene must, as he said, have been fearful.

“You could not tell her then, of course, Will,” I said pitifully; “but afterwards? Surely you could have told her afterwards?”

“I dared not,” he said thickly; “I was afraid. Olive would have hated me, and I dared not risk it.”

“But the pistol? Didn’t they try for some weapon at the inquest which the bullet might fit? It was in your possession.”

“No, it was found in the lane. I must have rushed up to Robin with the thing still smoking in my hand, and then have thrown it from me. I had picked it up second-hand in a shop in the city. No one knew I had ever thought of buying such a thing: there was no possibility of tracing it.”

“But I—But surely someone must have noticed the report?”

“How could they with that perpetual firing in the next field?”

I sat silently thinking, until at length I recalled the gossip of the townspeople. “Who is Jake Ilford? How came his name to be mixed up in it?”

“He is the poacher I told you of, who, I believe, was the man who wrote me those threatening letters. They came anonymously, of course, but Ilford had a grudge against me for what he chose to consider hard dealing. He was seen hanging about our grounds a day or two before, and at the inquest a witness who had seen him started the rumor that he was probably the guilty man. They tried to find him, but he had gone away from here before they were on his track. He had some relatives in America, and it is thought he went to them. Blair! what shall I do?”

The sudden question was fraught with all the anguish which hitherto he had successfully kept under control, and the poor fellow held out his hands to me as if his salvation depended upon my answer. I grasped them firmly.

“Get rid of this Rutton first of all,” I said earnestly. “He can’t find out anything—there is nothing to find out, but the knowledge he is in the house will so alter you that you will betray your own secret. And then go abroad with Mrs. Seagrave, and live in some big town. The bustle and novelty of the place will serve to distract her even if you keep quite to yourselves. Nothing but time can help either of you, but matters will never grow better if you live here with your mind continually dwelling upon the same subject. Six months will make a wonderful difference. You will find her sufficiently like her old self for life to be at all events peaceful again.”

He snatched gratefully at the first ray of hope which had come to him for months.

“Do you really think so, Blair?” he cried. Barely had the words left his lips when I caught the sound of a light foot-fall in the passage, and I had hardly time to move away from him and plunge into some irrelevant question before the door opened softly, and Mrs. Seagrave came in.

I felt as if my heart had stopped beating as I glanced at her, but no, she had evidently not heard anything. She was restless and ill at ease; I could see that by the way the thin hands were pulling at the lace upon the soft white wrapper, but that she had not been spying upon us was proved by her first words.

“Do come to bed, Will,” she said querulously. “It is nearly two o’ clock, and I am tired of waiting.”

Seagrave rose at once. “Why, my darling, you should not have done that. Haven’t you been to sleep?”

“What do you mean? Have I not as much right to sit up as you have?” she demanded sharply. I heard afterwards that she had employed the time by going over the whole miserable story again with Rutton, and her nerves were consequently strung to the highest possible pitch.

“It is quite my fault, Mrs. Seagrave,” I said remorsefully. “I have been keeping Will up to listen to my stupid traveller’s tales. I will say good-night now, if you will allow me. Good-night, Will, old man.”

“Oh, don’t go, Dr. Royden,” she said at once. “I feel so wide awake now that I would rather sit and talk to you both. See! shall I fill you a fresh pipe? Will used to say I was a very good hand at filling a pipe. I almost think I could smoke one to-night,” and she went into peals of laughter.

I did not like it at all. Her eyes, which were usually so lustreless, were now glittering brightly, and though her laugh was noisy, it was utterly mirthless.

“Please sit down again,” she repeated, more imperatively, and I obeyed. “You shall tell me some traveller’s tales too. Or no, I know nothing of foreign life; let us talk about London.”

I telegraphed my amazement to Seagrave, but he was leaning his head upon his hand and I could not see his face. Neither did he take any part in the conversation that followed, never rousing from his moody silence while his wife chatted gaily about the theatres, the rival Hungarian bands, and the charm of little Hoffmann’s playing. Had it not all seemed so unnatural I should have been well entertained, but as it was——

I hurried through my smoke, and again tried to make my escape. “It is really so late, Mrs. Seagrave.”

“Is it? I suppose it is,” she answered vacantly, and to my dismay the brilliant, incisive speech had again been changed to the dull, monotonous tones I had learned to dread. “Do you know if the maids have gone to bed? I suppose Rutton is still up?”

“Rutton? Ah, I want to talk to you about that man, Olive.”

It was done before I could stop him. Evidently he had been working himself up to follow out my suggestion, and had caught at the name as an opportune chance. Unhinged as he was by what he had just told me, nerveless as the recital had left him, it was the very worst moment he could have chosen to make the trial of his strength. Possibly he felt it easier to speak at a time when my presence would necessarily cut the matter short, but I knew it was fatal when I looked back from his face to hers. Into Mrs. Seagrave’s had crept—how shall I describe it?—a sort of horrible expectancy which carved deep lines about her mouth, and gleamed sullenly in her eyes. She seemed to be lying in wait for her husband.

“Yes? What about him?” she asked, in a low, strained voice.

“I think we had better get rid of him, dear.” Seagrave never raised his eyes from the carpet at his feet. “I heard to-day that James” (the man servant whom Rutton had temporarily replaced) “is fit for work again. We should not be acting fairly by him if we did not offer him his own post.”3The original omits the word “if” and the “i” in “him.”

“Why do you want him to go? Why? Why?” the rapid question cut into his carefully-weighed words as though their import had not reached her ears. In the breathless silence that followed, she rose from her chair, and with an unsteady, wavering run crossed to her husband’s side. “Why? Why?” she repeated wildly, laying burning hands upon his bowed head. “Look up, Will, look at me. Do you know who Rutton is?”

“Will! Rouse yourself!” I cried sharply. “You have just been telling Mrs. Seagrave why you wish the servant to go.” But neither of them heeded me.

“You shall look at me,” she muttered, and in another moment she had forced his head upward, and their eyes had met.

It would have been a long and harrowing scene upon the stage: in real life it was mercifully short. After that one searching look into those eyes which so furtively scanned hers, and in which despair was only too plainly written, Mrs. Seagrave stepped back for half a pace and put her hands convulsively to her throat.

“You—you killed—him!” she gasped, swaying for a moment helplessly to and fro. “My—my——” Before I could catch her she had fallen, and lay like a dead thing at our feet.

In the course of the following day I started the detective back to town. When I told him that if I pulled his unfortunate employer through the illness of which last night’s fit had been the precursor it would only be to install her in some asylum, and when he saw the formidable array of physicians and nurses who were wired for from town, I think he felt he had made rather a mess of this, his first, murder case. I told him that, fearing her mind was giving way, Mr. Seagrave had sent for me to live in the house, and so keep better watch over my patient. Of course I had immediately recognised the supposed groom, for I had seen him at Mr. Drayton’s—how amazed the fellow looked—but I had kept my own counsel, as any thwarting of the poor lady’s plans might have hastened the disease.

So I talked, and so in the face of present events he was forced to believe. He went away reviling himself for having given credence to the vagaries of a failing brain; and for once I breathed the easier for his absence.

Matters rest very much as he left them. After a weary two months’ confinement, which she passed in the belief that little Robin was alive and hidden away from her, Mrs. Seagrave died in the asylum where we had placed her. Will is still travelling in the East: the children have been placed with friends. I please myself sometimes by imagining that, when time shall have blunted his double sorrow, and Dulcie and her little brother have grown to a more companionable age, the three may live together again. But if the children can persuade him to give up his wandering life, they will never have to content themselves with some foreign city. He will never come home.

Word Count: 7010

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Mabel E. Wotton. “The End of the Tragedy.” The Argosy, vol. 50, no. 3, 1890, pp. 164-76. Edited by Rachael Riner. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 2 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-end-of-the-tragedy/.

Editors

Rachael Riner

Nicole Clawson

Lesli Mortensen

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

11 October 2016

Last modified

1 July 2025

Notes