The Height of The Ridiculous

by Anonymous

Forget-Me-Not, vol. 1, issue 3 (1896)

Pages 32-43

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Height of the Ridiculous” is a short romantic story about a woman who is trying to navigate society, and find love. She meets an artist who has given up his craft, and they form a close relationship. Written for middle class women, this story adds a twist on the typical marriage plot that might be found in the first British literary annual, The Forget Me Not.

CHAPTER I.

“There’s no use your sitting there, Janet, shaking your head. I mean you to come to the Ardennes with me.We start to-morrow night.”1Ardennes: a forest region primarily in Belgium, but extends into parts of Germany and France.

“What an impetuous creature, you are Freda! Do you really mean that you are going to set your aunt at defiance, and Mrs. Grundy at defiance, and propose journeying off with me for three weeks to the Ardennes?”2Mrs. Grundy is a well-known English fictional character who often represents the censorship enacted in everyday life by conventional opinion. She first appears in the 1798 play, Speed the Plough.

“Exactly.”

“What put the idea into your head?”

“I shall tell you that in a month,” she says. “Come, Janet, look at it in the light of copy-pure copy. Think of the adventures we are sure to have: think of the articles you will write; and all for ten pounds- positively for ten pounds!”

Janet Carnegie certainly sees the point of this. Her sister, who is a hard-working governess, will back Freda’s proposal, she knows, and as she thinks over the plan her face clears more and more.

“Don’t think I don’t want to go, Freda. It sounds lovely, and I am tired, O, so tired! of pen and paper.”

“No wonder,” Freda says; “and you are getting so thin, Janet, and losing all your country colour. I consider it all quite settled.”

Freda Dunsterville winds the pretty feathery boa round her neck, nods gaily, and then takes herself out of Janet’s dingy little sitting-room.

Janet gets up from the table with a wide-awake and excited look that is a pleasant change from the tired and rather harassed expression of a few hours ago, and puts on her hat and takes a penny ‘buz into The Strand.

She walks along till she reaches a particular office, and there she mounts a rather dirty stair and knocks at a door marked “Private.”

“Come in.”

A young man gets off his stool promptly when he sees his visitor, and, after carefully shutting the door, stoops down and kisses her as if that were a matter of course.

“Janet, you are a sicht for saier een! But what has brought you Citywards?”3Sicht for saier een: “a sight for sore eyes” in the Doric Scottish dialect.

He is a very pleasant-looking man, this lover of Janet’s, with clear, thoughtful gray eyes, and thin, rather worn features. Janet’s clever face softens wonderfully as she looks up at him, and she gives him one of the rare tender smiles which only he and Molly ever see. It is a smile that makes her face beautiful.

“Freda Dunsterville has been in, like a small whirlwind, Hamish, and she is going to carry me off to the Ardennes.”

“To the Ardennes? When?”

“To-morrow night. Freda says we are going to have all sorts of adventures. But I must not keep you. Good-bye, Hamish.”

He goes down-stairs with her, and they part with a tight hand-clasp, and a long trusting look. After all, as Janet thinks, what does anything in the world matter, as long as they love each other? Poor prospects, hard work, and brains that every now and then faint and fail a little under the burden and beat of the day. What are these to Love, that still is lord of all? “Nothing,” Janet says to herself, “nothing.” But then she is a woman, and addicted to light fiction. The world and Mrs. Grundy would set her down as a harmless lunatic. But the thought gives elasticity to her step as she moves through the busy crowd.

Next evening really finds Janet at the station with Freda and Molly, though she had half fancied it would all turn out a dream. Freda is in the most brilliant spirits.

Presently a tall and exceedingly good-looking man presents himself at the window and raises his hat. Freda sits rather upright, and nods in an extremely dégagée manner.4Dégagée: French for “clear.”

“Did you think this was expected of you, D’Arcy?”

“On the contrary” -he has turned to her after shaking hands with the other girls- “I expected a cold reception, but I thought perhaps you might need a man at the last moment.”

“Of course,” and Freda’s head goes up an inch or two; “men think they are necessary always. We don’t need you, D’Arcy. There is Janet’s bag; my box is in the van; here our our wraps; there is the basket with brandy for the voyage and sandwiches for Janet.”

Molly says good-bye, and Freda gives him her hand lightly and carelessly.

“For three weeks you are to play Una?”

“For three years if I like. Au revoir. You can go and see auntie, and groan together in a duet over the nineteenth-century girl. Good-bye, D’Arcy; I’m sorry you were not born thirty or forty years ago. You’re out of date.”

That is the last remark she makes, for the train starts then, and he is left to take off his hat in the most dignified matter possible, and then turn to Molly, who has already taken a step away.

Janet laughs.

“How you tease him, Freda!”

“D’Arcy lays himself open to it,” her friend retorts. “All his life he has been adored and bowed down to by kneeling female relatives. He has got into a way of expecting it. I took him in hand a year ago, and we have quarrelled steadily ever since. He thinks this is my final rebellion; now I am beyond the pale, and in three weeks I am of age and can do exactly as I like!”

Janet’s thoughts have wandered to Molly going home to the quiet lodgings, lonelier than ever now, and to a certain hard-working sub-editor who had no-time to come and see her off, and she does not think anything more of Mr. Mandeville and his views upon the girls of the present day. She thinks probably she may leave him in his cousin’s hands.

CHAPTER II.

“To think that we are really in the heart of the Ardennes! Do you know that, Janet? Do you feel it?”

Janet, who is lying back against a tree, picking idly at the little brittle pine-needles with which all the ground is covered, opens her eyes lazily. Freda says that she knows no one who can be so perfectly lazy as Janet, just as she knows no one who can be so fearfully energetic.

“No,” Janet says slowly;” I don’t feel it. When I opened my eyes just now I expected to look out of the window and see a charming vista of chimney-pots, and a pleasing variety of dirty cabbages in Mrs. Steele’s back garden. I don’t feel in the Ardennes at all. It is too good to be true!”

She stretches out her arms as she concludes, looking over at Freda with a young and happy laugh that makes her friend smile.

“And you are such a very pretty figure in my foreground, Freda,” Janet says. “I enjoy looking at you as I enjoy the asparagus. There is no doubt that you are a very pretty adjunct-”

“Thank you.”

Freda has all her life been so perfectly aware that she is fair to see that she is now entirely indifferent to the fact, which is, I suppose, a form of vanity though a harmless one. Now, with the sunshine slanting through the trees, and resting on her olive-green gown and ruffled golden hair, her white sailor-hat tossed to one side, and her blue eyes regarding Janet with dimpling and sparkling amusement, she is quite irresistible.

“No,” Freda murmurs, after they have started for their hotel; “it is very lovely, but we want human interest, Janet. The setting of the scene is all right, and worthy of Hawes Craven; now we want the dramatis personæ.”5Hawes Craven was an English scene painter.

“Here is the human interest!”

“You little witch! Where?”

“Coming over the bridge- and he is coming here!”

A tall man, with a slight stoop in his shoulders, and an absent-minded face, the features roughly hewn, and lit by a pair of bright and yet dreamy eyes of a quiet gray, is indeed advancing, followed by a rough, yellowish-brown Yorkshire terrier, intelligent of aspect, though slightly wanting in the article of tail, and the two are evidently bound, indeed, for M. Meuiner’s.

As they approach, Freda and her companion make their way through the sitting-room and salon, and up a little flight of steep stairs to their own room, where they can hear the stranger explaining himself and his wants to the old man.

Freda is sitting on the window-sill of their room when these sounds come up to them, looking down at the river, while Janet combs out her nut-brown hair and washes her hands.

“Your human interest is rather elderly, Janet.”

“He looks as if he had lived a good deal,” Janet says. “But even the glance I got made me like the face. He struck me as being interesting.”

“He struck me as wanting his coat brushed. And his hair was gray about the temples. But though he is not artistic nor velvet-coated and long-haired I shall don my new blue blouse. At least he is a man.”

“Be quick,” is all Janet says; “I am ravenous.” And then they hear a bell, and she goes off without waiting for Freda, who does nothing till the last moment. And as this is no formidable table d’hôte, but the most primitive of meals, Freda hears her go with equanimity, and betakes herself to her toilet and the blue blouse.6Table d’hôte: French for “Host’s menu.”

When Freda enters the salle finally, Janet and the stranger have finished their courses, and are absorbed in asparagus and conversation. Freda hears the man’s voice as she descends:

“But in Munich they laugh at English art as much as they do in Paris.”

“Then he is an artist?”

And then he looks up and sees her standing in the doorway, and he stops short after a quick look that is very respectful and friendly, and drops his eyes on his plate. Freda’s hair seems to have caught all the sunshine left in the sky and imprisoned it; she looks tall beside Janet, who is short and sturdy, and there is a delightful willowy grace in the slender figure in its blue cotton gown. When she sits down, and Janet introduces Mr. Roland Rood, she smiles over at him frankly, and they are soon all three talking as happily as if they had known each other for days-days count as years on the Continent when English people meet-and they have a very charming supper indeed. It is almost over when Joseph, hastily called downstairs by the chambermaid, shows in a elderly man, who takes his seat with dignity, after a brief glance at the girls and a fat Belgian, who is taking his supper with fearful solemnity at the other end of the table.

Whether from hunger or natural peculiarity in temper, the old gentleman is evidently not prepared to be friendly, but in a few moments, when he has disposed of soup and cutlet, he makes a remark to Freda with such amiability that she veers round at once, and they are soon all talking as if such things as British frigidity and reserve had never been known.

One could not call it dark outside after supper, and when the girls appear with their hats on, the two men beg very humbly that they may act as escort, the Yorkshire terrier, who is called Bob, hovering round in much excitement. So they all sally forth, Mr. Rood and Freda first, Janet and the old man after. Janet has not yet got rid of her Scotch reserve, but Mr. Bathurst is so full of anecdote, and so delightfully fresh and racy in his description of his previous Continentinal journeyings, that presently she forgets to be shy, and her pretty laugh ripples out again and again. They stroll round the village and then home, while the stars peep out one by one, and all the village seems wrapped in slumber; and then Janet, who on her holiday is a dreadfully sleepy person, goes off to bed, lulled by the murmur of the river at her ear.

Freda follows her example, and the river soothes them both to the sweetest and most unbroken slumber.

CHAPTER III.

Next afternoon the girls forsake their favourite pine-wood, and go up to the Castle, begging the key from the caretaker, who tells Freda to leave the gate open, and then, her heart gladdened by a franc, which seems untold wealth, she watches them go up the sun-shiny street with an indulgent smile. After a brief visit to the battlements and to the salle des chevaliers, they seat themselves under the pine-trees.7Salle des chevalier: French for “Hall of the Knights.”

It does not seem to surprise either when a tall figure appears presently, followed by Bob, and Mr. Rood delivers to Freda a letter, sitting down after with a very contented and long breath.

“May I? I am not disturbing you?”

He asks the question so humbly, and yet with such a wistful look, that Janet says “O no” hastily while Freda begs leave to read her letter, putting it away in a moment with a curious little smile, as if it amused her.

Freda commences to put ivy-leaves in her hat, and studies the effect amongst the lace, her golden head on one side. She sighs at last, and puts it down.

“I am afraid I am not artistic. You are an artist, are you not, Mr. Rood?”

He rouses himself then with a sigh.

“I studied art in London, Paris, and Munich, and I once thought I was going to do great things. But I just missed it; and now I never paint. I had a bad illness once, and my father lost all his money. We had all to do what we could, so I went into business. Not that I made much of that, but I can make both ends meet, and I am able to take a holiday like this, and the old man was comfortable in his old age.

He speaks almost dreamily, but Freda looks at him in amazement.

“And you could give it up like that, when you once hoped to do great things?”

Her tone seems to rouse him, and he looks at her suddenly, repeating slowly:

“I just missed it. The professors at Munich, even the big ones, said I could do very good work; but I could not be content with anything but the best, and so I gave it up. That was partly my illness. I used to think I could have painted one thing well-as I call well.”

“I would never give up till I had, if I were you,” Freda says, clasping her hands. “To have talent, the one thing in the world the world cannot buy, and not to use it!”

“When I try to paint now it makes me ill,” he says restlessly, and Janet notices a little red spot burns suddenly on his thin cheek; “the old fever begins to burn in my veins.”

“Had you ever anything in our Academy?”

“I only sent once,” he replies-“two pastels which I did in two afternoons, and they were taken. I liked oils best. At Trouville I did fifty portraits once; it was good practice. They used to say at Munich I had a gift at portraits. I could paint you.”

He has turned rather abruptly to Janet, and she opens her eyes widely.

“I don’t see what you would find to make a good picture of in me,” Janet says in her blunt honest way. “I have just the conventional type of face that makes no picture at all. Of course I may be wrong.”

“I did not think of the picture,” he says gently; “I meant your face would be easy to do, and pleasant.”

Freda just then pours out the tea, and he lets her give him a cup with a very grateful “Thank you.” He does not hasten to help her or make any of the graceful speeches she is wont to receive from young men; he only drinks the tea slowly, saying presently in a tone that makes the girls laugh:

“This is lovely!”

“The tea?”

“Everything. To be sitting here with you. It is very good of you to let me come. I am a very solitary man at home, and I see very few ladies. That makes me slow and absent-minded. I suppose; and I get sulking and forget I may be a bore.”

But they do not find him a bore, and presently, the talk drifting to art and art centres, both girls are hanging on his words. He has led a strange roving life, in London, in Munich, in Rome, in Paris; then, when he gave up art, in France and New Zealand; now he is in business is Antwerp, settled there for life, he says.

A long pause then ensues, which is broken by Freda, who, happening to turn full in Rood’s direction, notices him very busy.

“What are you doing?” she says.

For he is sketching quietly and now he looks up and tears out the page with a guilty start.

“I am afraid I was trying to sketch-you.”

“Really! Do let me see. No one ever sketched me. Why won’t you?”

He looks pleased and surprised.

“I only did it when I forgot. Would you really permit me?”

“Why, I should love it! A real picture would be best; won’t you make a picture of me?”

“Would you allow me to try?”

“Why, I should be charmed!” Freda cries, sitting up. “Now, in the pine-wood and just here, for you can catch a glimpse of the Ourthe through the trees behind me.”8Ourthe: a river in Belgium.

Rood is too busy to talk. Janet watches him quietly. She thinks he is right; art is too exciting an occupation for him. He seems a different man just now; the quiet and the peace have left his face, the forehead looks lined and furrowed, the eyes eager and excited; his lips twitch and his nostrils work, and presently he shuts the sketchbook with a long breath.

“I cannot do any more to-day.”

“But you will go on with it?”

“Do you really wish me to?” He asks gently. “Would it please you?”

“Indeed it would.”

“Then I will,” he says. “I will get out some canvas to-morrow. I always travel with my implements; it is an odd habit, since I do not paint, but it is custom.”

“You won’t have time to make this the picture,” Freda says presently, stirring the pine-needles with her slim fingers; “for this is actually our last Sunday here. It is sad to contemplate.”

He looks up sharply.

“Your last Sunday?”

“Yes; Janet says we leave on Saturday. You know we travelled about Belgium before we came here. Can you paint from memory?”

“Yes.”

“We shall have been three weeks abroad on Sunday,” Janet says. “It seems three months at least since we were at Dinant, and I feel as if my brain and mind were stored with ‘copy.’ Don’t mind my talking like that. Mr. Bathurst has told me such amusing stories, too; and O, I feel so rested! I was never so happy in my life. But for one thing La Roche would be Paradise.9La Roche: A City in Belgium, translates to “The Rock.”

They do not ask her what that one thing is. Freda knows, and Rood does not seem to hear.

The first day at La Roche ends very happily, and they all retire early. But Rood, whose room is just under the girls’, and who can hear an indistinct murmur of talk, and now and then a low ripple of laughter which he knows to be Freda’s (Like Mrs. Jordan of old, she has the most “swindling laugh”), does not go to sleep. He opens his lattice wide; the river is bubbling and rippling and splashing over its pebbles just below; he can see the black pines on the Castle’s height, dark against the pale sky, and he sits looking out for a long time. Then he hears some one open the window above and fling it back, and he hears Freda’s voice singing softly, with the river’s flow as accompaniment. She is singing one of the sweetest solos ever written, exquisite music wedded to exquisite words, and very softly, very soothingly, as only rare voices can sing: “O rest in the Lord; wait patiently for Him.” And then her song dies away.

Rood does not retire. His face has grown restless again, his lips twitch and tremble, his eyes shine. He takes out the sketch and bends over it with a hunger of longing in his eyes.

“Is it possible? Possible! Am I mad? To come to me now, now, when I am getting old? I, who will never be rich, and who am so rough and unlearned in woman’s pretty ways! But how her eyes shone when she said fame could buy love, and that a woman could be won by a great picture, painted for her sake! And if I could make this the success of my life, the thing I have fought for and toiled for, and never reached! I feel as if I could, for her sake. At last, at last, to win her by fame! Or am I mad?

And then the sketch-book drops from his hands, and he lets his head fall forward on the window sill. Freda and Janet slumber peacefully above, Janet dreaming of a certain hard-working sub-editor far away in London who seems to call her to come back to him; Freda smiling in her sleep, as she had smiled over a certain letter read at the Castle and had left unanswered, and the river murmurs placidly below. But the first streak of dawn is in the east before Rood moves. And then the fever and the restlessness are deeper in his face.

CHAPTER IV.

On Monday, Janet is attacked by one of her worst headaches, and there is nothing for her but perfect rest, and a little stroll up the hillside in the evening with Mr. Bathurst in attendance. And till Thursday she dares not venture out in the heat of the day. Freda and Rood go off to the pine-woods alone, and Freda reports that her picture is growing apace, and that Mr. Rood is to make a large canvas from this small one. She is quite excited over it, and interested in the matter, and never fails to give Janet a full description of the full day’s conversation. Mr. Rood does not paint for very long at one time, she tells Janet, he seems to get so excited over it, and then the canvas is put carefully away, and he smokes and talks telling her innumerable and interesting narratives. She very often winds up with the declaration that he is quite the most interesting man she ever met, and her belief in his talent grows greater day by day.

“And would it not be splendid, Janet, if my picture brought him fame?”

They are sitting by the open windows of the salle-à-manger when she says this, and it is the half-hour before supper.10Salle-à-manger: French for “dining room.” Rood and Mr. Bathurst are smoking on the bench at the other side of the street, Bob contentedly crouched between them, and below in the salon they can hear Marie singing over her work.

Janet, pale and heavy-eyed still, though she is much better, lifts her eyes to Freda’s as she speaks.

“Would you care, Freda?”

“Care?”

“I mean, would it please you very much?”

Freda opens wide her blue eyes.

“What do you mean, Janet? I should be delighted if Mr. Rood made a hit-perfectly charmed!”

“O yes, so should I,” Janet says, sighing a little,“but I did not mean that, exactly. Something in all this troubles me a little.”

“In all what, most cautious of little mortals?”

“You will probably laugh at me, Freda.”

“I am bound to say I think that more than probable.”

“But I don’t care! I am going to warn you. You know, Freda, you are a very fascinating girl-”

“Thank you.”

“Don’t laugh, please- and you are very frank and gracious. It seems natural to you to make people like you- it seems a second nature; just as it is a second nature to me, to avoid strangers and shrink into my shell; and I think you forget, Freda, that it may be dangerous to be quite so friendly and frank to men- that they may mistake you, and they may suffer through their mistake.”

“Janet, what are you driving at?”

“Plainly, then,” and Janet is almost aggravated,”I don’t want you to be so nice to Mr. Rood.”

“Why not?”

“He may grow to-love you.”

Both men hear the merry peal of laughter that ripples out as Janet concludes.

“If that is not the height of the ridiculous! O Janet, Janet!”

But Janet does not smile.

“What is the ridiculous?”

“My dear Janet! Mr. Rood is over forty if he is a day!”

“Do people over forty never fall in love?”

“I’m sure I don’t know. Probably they form mild and lukewarm attachments- I really never studied the subject- but they don’t fall in love with girls of my age.”

“I don’t think you know anything about it,” Janet says.”A man who loves at forty does not love lightly.”

Freda shrugs her shoulders.

“My dear Janet, a long course of light literature has distorted your mental vision. We are not characters in a novel. I am an exceedingly practical girl, and Mr. Rood is a very delightful and very sensible middle-aged man- at least, he seems middle-aged to me.”

“I don’t care what he is! It is quite possible that what I suggest is true, and many a girl would be proud to win the love of such a man; any woman might be proud to be loved by him”

“I am sure I perfectly agree with you; and I wish she would cross his path and look after him, and make him buy a new coat. And then that velvet collar! He has really a handsome head, but that greeny-brown velvet collar! It would prevent any girl- with the least-”

And then she stops, her voice bubbling over with merriment.

Janet’s pale face is flushed and her eyes flash; for once Freda sees the little fiery Scot in one of her “real Highland rages,” as Molly calls them.

“Freda, don’t make me despise you.”

“My dear child!”

“You can talk to him, and let him bare his heart to you, and show you all his brave good life, and then laugh at him.”

“I did not laugh at him; I laughed at his collar. Why should I not? I did not laugh at Mr. Rood.”

“It is all the same. Freda, it is unworthy of you!”

But Freda will not be made angry.

“You are feverish, Janet,” she says soothingly, though her eyes sparkle still, “and I will not permit you to excite yourself like this. Come, what is it you want me to do?”

She is really fond of Janet, and she lays her hand on the shoulder next to her affectionately, with a little laugh.

“Come, Janet, let your angry passion cool down. I will be good, as the children say; oh, I will be good! What shall I do?”

It is rather difficult for Janet, who is in earnest, to answer the little mocking spirit that peeps out of Freda’s face, but she does her best.

“Show Mr. Rood that you regard him merely as an acquaintance.”

“How does one do that?”

“You know quite well. And then he thinks you are poor, like me. You ought to let him know.”

“I ought to flaunt my wealth in his face, and say, ‘You are a poor man, and I am a rich girl; avaunt!’ Thank you, Janet; I decline to do that.”

“Well of course you make me out in the wrong,” Janet cries.”But I don’t care; I know I am right.”

“My dear, you are running away with a very nonsensical idea. Get rid of it. Mr. Rood is meditating no such madness; he is far too nice. Men in love are odious and ridiculous objects, as a rule. Don’t be angry; I except the sub-editor; and could any one be nicer or more sensible than Mr. Rood? Come Janet, put off that little frown. Here is Joseph. I will be like Maud, icily regular, splendidly null, all the evening.”

Janet says no more, for the men are mounting the stairs, and presently Joseph brings supper, and Mr. Bathurst has just recollected a most delightful anecdote, not recounted before, and soon all three are laughing as if there was not a shadow of care in any of their hearts.

Freda forgets her resolution, of course, and she talks and laughs much as usual, and she goes off for a stroll with Rood presently in the soft pale light. They mount the hill slowly to the Castle, and look down at the lights in the village; they can see the hotel, and Freda declares she can see the red end of Mr. Bathurst’s cigar, which is of course a pleasing little fiction.

They lean over the battlements together, Rood very silent, and Freda thinks him not so entertaining as usual.

“Do you think you and Miss Janet will ever return?”

Freda smiles.

“There is so much more to see.”

“And do you go about like this always, you two?”

“We never have done so before. Are you shocked?”

“Shocked!” and he laughs.”You and she could go anywhere.”

“Thank you. That means a compliment, I know.” Freda is gathering a bunch of the black ivy-berries and fastening it into her waistband. “I shocked my relations and some friends very much, but they told my ‘gang my ain gait’! One friend prophesied I should have to send home for an escort, or return thoroughly disgusted, and instead of that Janet and I are charmed with everything, and have made two friends. O no; we shall never forget the Ardennes and La Roche.”

He looks at her eagerly.

“And I-I shall never forget La Roche. I cannot bear to think there are only two more days. It has been such a happy time. I-” and then he breaks off.

Freda is smiling a little, as if she scarcely heard him. He wonders what she is thinking of, and then she looks round abruptly.

“And you will finish my picture? And make it the picture?”

“If you wish it, yes.”

“Of course I do. And you will bring it to London and show it to me? Send it to the Academy, not to the Salon; but first you will show it to me?”

“Yes, I will bring the picture to you.”

He speaks with a curious repression in his voice, though his pulses are throbbing wildly, for Freda’s eyes and voice are alike eager, and she is looking full into his face. To do her justice, she forgets Janet’s warning. She is quite sincere in thinking it the height of the ridiculous that Rood should ever love her, it is only one of Janet’s romantic notions; and she likes the artist very sincerely and admires him immensely, and she thinks him quite thrown away in Antwerp. It will be a splendid thing to have inspired him to return to art, a splendid thing that he will win fame and wealth through her!

“And where shall I find you in London?”

Freda smiles as she answers:

“I am a great wanderer, Mr. Rood, and I do not know where I shall be. But if you write and ask Janet, she will always be able to tell you. You have her address?”

He says “Yes,” and then the ten o’clock strikes slowly from the church tower, reverberating up the hillside and they go down the ruined steps of the escalier d’honneur, and so into the sleeping village. Mr. Bathurst is still smoking outside the hotel, but he says Janet has gone in; and Freda, saying good-night and giving her little slim hand to each man, joins her friend. But Janet is writing to her lover, and Freda moves over to the window, where she takes out a sheet of very thick note-paper on which there is a good deal of crest and monogram. She has read this letter pretty often, but she does so again, still with that latent blush and sparkle of mischief in her eyes.

It runs as follows, beginning with no prefix:

“I suppose it was part of my punishment to leave me with no letter for a fortnight; but I ascertained your address from Lady Sanley, who tells me you are well and apparently in the highest spirits. It will be just like you to declare you never enjoyed any time so much in your life; and she says your letters are a jumble of diligences, woods, churches, peasants, and artists. On the head of the letter I shall have something to say on your return. We shall see! I met Mr. Dupont yesterday, and he shook his head very much over you. He said he would be extremely relieved when December 4th came, and he had no longer any responsibility in the matter. I hope you will let me know whenever you return. Am I not punished sufficiently? London is a howling wilderness.-

Yours,

D.M.”

And then Freda folds this note and puts it away in her desk. Janet is putting her thin sheets into an envelope and yawning sleepily, and Freda seems to be in a dream. She is not thinking of her friend’s homily or of Rood at all, nor is her mind, indeed, in any portion of the Ardennes. And yet, just as she is falling asleep, Rood’s face, as she had seen it in the moonlight on the battlements, looking into hers with that sudden passionate glance, flashes before her.

“He means to succeed?” she thinks sleepily. “He is determined to win fame. I am so glad! And I am sure he will. He is so nice!”

The last day seems to go very fast, and Freda and Janet revisit all their favourite haunts, and Freda insists on looking into all the little shrines and saying good-bye to the church and to the curé of La Roche.

Mr. Bathurst has revived a little; he has made up his mind that he will see the girls in London shortly, there is no use to fret over the parting.

“And when I get back to town, you will both dine with me, I hope,” he says, addressing both, but looking at Janet, for there is no doubt she is his favourite; “and we will have no kickshaws. Our second course will be boiled mutton and caper sauce. After three weeks of kickshaws, I positively pine for boiled and roast.”

Rood is rather silent again, though he smiles now.

“You will miss this wine, Mr. Bathurst. One cannot get it so light and cheap at home.”

“No, you are right; it is our heavy ports and sherries that are the cause of all the Englishman’s gout. I own that we are behind the day in our wines. And nobody makes the old-fashioned wines now-adays-elderberry, and gooseberry; and, ah! I have had such memories connected with gooseberry wine.”

“Sentimental memories?” Freda cries. “Do tell us all about them, Mr. Bathurst! When you talk of gooseberry wine I conjure up the prettiest picture, and I see you taking a glass of it, handed you by the daintiest damsel in a pink-flowered chintz gown and a mob-cap.”

“I don’t remember the cap.”

“But you remember the damsel, the Hebe?”

They have finished supper, so they betake themselves to the salle down-stairs, where the men gain permission to smoke, and Janet takes out her embroidering.

Freda, with the elbows of her blue cotton gown on the table, and her bright face full in the lamp’s glow, is opposite Mr. Bathurst.

“But the damsel? Do tell us.”

“Yes,” he says in his deliberate way. “The damsel has never been forgotten! She was a second cousin of mine, and her name was Patty-rosy-cheeked Patty- and she and I were sweethearts.”

“And where is she now?”

“I have not the slightest idea. She was seven and I was eight, and when I saw her first she had on a pretty pink frock, and her hair was tied up with pink ribbons. She was Scotch, and her mother gave me cake and gooseberry wine. I remember it made me horribly ill after, but I thought I enjoyed it at the time; and Patty took sips out of my glass.”

“But you don’t know where she is?”

“I never saw her after that summer. I remember her brother played on the spinet ‘The Banks of Allan Water’ and ‘Barbara Allen,’ and Parry had the sweetest little voice. Ah! It is our Patties, our cheery-cheeked Patties, that we old men think of in our lonely ingle-neuks.”

“My mother’s name was Patty,” Janet says.

“Was it indeed? I love the little name. I was taken back to England after that summer, and I never saw my little cousin again. I don’t think I even heard of her. I have sometimes thought of getting my man of business in town to find out what became of her, and whom she married. Though I think of her as anything but a little maid in a pink frock, she ought to have married me. We exchanged ‘sweeties,’ as she called them, and a sailor uncle of hers who was at home at the time tattooed my initials on her arm, and hers on mine. She-”

“What were your initials?”

Janet makes the interruption with a start of surprise, and her embroidery drops into her lap unheeded.

“‘G. S. B., and hers were ‘P. C. M.’ Patty Charlotte Maclaren was her name. I remember getting a caning from a very severe old uncle for allowing the thing to be done and I fancy poor little Patty got a scolding too.”

“Patty Charlotte Maclaren? That was my mother’s name.”

“What!”

And then Janet laughs rather excitedly.

“Indeed it was, and she had initials tattooed on her arm- ‘G. S B.’ She used to show them to us. And she said they were the initials of a little English boy, a kind of cousin.”

Mr. Bathurst lets his cigar go out unnoticed.

“My dear young lady! And your mother- is she alive still?”

Janet shakes her head.

“She died a great many years ago, and my father died a year after her. Molly and I came to London, and Molly is a governess.”

“Isn’t this romantic?” Freda cries.

“But this is most extraordinary, and most interesting,” Mr. Bathurst is saying. “I have almost no relations left- no near relations- and now to find a charming young lady poor Patty’s daughter! I can scarcely believe it.

He moves over to Janet’s side of the table, and they are soon deep in conversation, he recalling more anecdotes of the past, she giving him her mother’s brief history. And when Mr. Bathurst returns to town he is coming down to Camden Town, he says to see her and Molly; and they must both come, and stay with him on a long visit. He has a house in Portland Square, and it will be charming to have them there.

Janet says they will be very pleased to come in Molly’s holidays, and then he asks where Molly teaches, and hems and haws a good deal over that, saying that they are both too young to work so hard and that they must each take a good long holiday. They must look after him instead, for he wants looking after very badly indeed.

When the girls go to bed at last, Freda does the packing while Janet for once sits on the bed and chatters. She and Molly have been so lonely in big crowded London that it seems delightful to think of their having a relation of their mother’s there, and that this relation should turn out to be Mr. Bathurst is startlingly pleasant, almost like fiction.

“Is it not strange, Freda? And do you know I liked his face from the first, ‘even when he answered Mr. Rood so gruffly that night.”

“He was hungry, and a hungry man is always cross,” Freda says. “It is really a most romantic and pleasing incident, Janet, my dear, and he is rich.”

“Is he?”

“I asked Mr. Rood. He says Mr. Bathurst is partner in a very good business firm in the City; he is a sort of sleeping partner, whatever that is. He only comes here because it is rustic and retired. And, Janet, he will adopt you and Molly, and give Hamish a berth that pays a little better than sub-editing. And then won’t you bless me and the Ardennes!”

“I bless them already,” Janet says, unclasping her knees. “I feel years younger, Freda, and so strong. And my brain is stored. Mr. Bathurst says he will be home the week after us.”

Janet has to write Molly of their newly found relation, so she is later in retiring; but she does not sit up late, and so for the last time she, too, falls asleep with the lullaby of the Ourthe in her ear.

The next morning a very curious vehicle which Joseph has obtained for them appears about eleven, and Freda’s dress-basket and Janet’s Gladstone bag are piled in front with the driver. The carriage is covered, though there is an opening on either side, and no door, and they get out the wraps at once, for though bright it threatens to be pretty cold. Mr. Bathurst says he does not know how he will get through the day without them, and he makes Janet promise again and again to come and see him at once on his return.

Finally, however, all the adieux are over, and they are off, Freda waving her hand gaily to the women at their doors. And soon the Castle is left behind, and the Ourthe, and the last glimpse of the pine-covered hillside.

Janet notices that as the day goes on Rood’s conversation fails a little, though he has talked perseveringly, chiefly on art; and when they reach Spa, and they have had tea, he begs that they will give him a final treat, a last favour.

“It is so fine, and I have two hours yet. Would you not let me take you a drive up the hill? It is a lovely drive, really lovely, the road winding through the wood all the way; it would be such a pleasure to me. You will let me do this?”

He begs so humbly that even Janet says, “O yes, it would be very nice;” and presently he returns with the carriage, and they drive through the gay little town, which is full of people dressed in very evident French attire.

They mount the wood-covered hill, and wind slowly up, meeting bands of woodmen returning home, and the men look at them curiously, and evidently admiringly.

They descend the hill again. And at last they reach the hotel, and Rood’s portmanteau is put into the carriage; he is to drive to the station. He stands utterly silent on the steps, while Freda bids him good-bye gaily and kindly; she has been so glad to make his acquaintance, and he is to come to London with the picture, and he has been so good to them, and they will never forget La Roche, etc. Janet says less, but her dark eyes look at him pityingly and kindly, and then he murmurs almost unsteadily that these have been the happiest days of his life. He can never forget them. They have been wonderful days. And- good-bye! A tight hand-shake to each, and he is in the carriage, and the girls standing on the steps, where Freda, who has taken off her veil, waves it gaily. He looks back once more, to see them standing there, Janet leaning against the door, Freda on the steps, smiling still, and he raises his hat. He does not smile. It seems to Janet that his face is gray, and his lips are locked together, and then he sits looking straight before him. She feels suddenly as if she had a pain at her heart, the pain of deep pity!

Next morning Freda has sallied out for letters, and she returns with a handful. Several are business ones for Janet, rejections and acceptances, mingled joy and sorrow, and one from Molly. Molly, brave Molly, has not been very well. She is sorry that Janet is coming home to worry, but she has fainted at her teaching, and the doctor has said she must rest for a few days, and Hamish has been to see her, and has been very kind. But he, too, has had head-aches, and been not very strong, so Janet must not be disappointed to find him looking thin. And Molly is charmed to think of having her sister home, though sorry for her sake that the lovely holiday is over.

Janet sits looking very grave, with this letter in her hand, and the old pathetic look of care settles down on her lips and brow. The quiet letter tells her more than the writer meant. She sees between the lines. While she has been enjoying her holiday, Molly and Hamish have been sinking under the burden and heat of the day, and they have not told her. She clasps her hands suddenly, and the tears rush into her eyes. “O my darlings! And I never knew!”

But Freda, coming in presently, will not let her sit with the letter clenched in her hand, and she refuses to look at the sad side of anything.

“Remember Mr. Bathurst,” she says. “He is to be the fairy godmother. Did he not say you and Molly were to rest? And something must be got for Hamish. Don’t you remember what Mr. Rood said, Janet: ‘God is too kind’?”

“O, I forgot Mr. Rood.”

“He is such a good man,” Freda says. “One respected him because he lived and did good, and did not preach. He never thought he was good.”

Janet is looking before her dreamily, and Freda puts her hand on her shoulder:

“Don’t fret over Molly and Hamish.”

“I was not thinking of them.”

But she does not say of whom she is thinking, and presently Freda forgets to ask.

“D’Arcy Mandeville says he is coming to meet us at Waterloo,” she remarks carelessly, “so I am to be looked after at once. Come, Janet, dejeuner est pret!11Déjeuner est pret: French for “lunch is Ready!”

And next day they sail from Antwerp. The Ardennes, Dinant, La Roche, Spa, are things of the past.

CHAPTER V.

At Waterloo, Mandeville is waiting, irreproachable in attire, smiling, immaculate, his “shining morning face” radiant with pleasure; but Janet has no one to meet her, and her face clouds a little. Freda smiles and blushes behind her veil when the tall figure approaches their carriage; but she receives his greeting very coolly, and she will not even permit him to see her home. Lady Sanley’s carriage is in waiting, and the three separate by it, Freda kissing her friend very warmly.

“I shall come and see you very soon, Janet. Give Molly my love. And I’m so sorry to part from you! No, D’Arcy; you are not to come.”

“I promised Aunt Fanny-”

“I can’t help that. I feel sea-sick still, and I cannot throw a word to a dog till I’ve had a hot bath and breakfast. You may come to afternoon tea.”

She gives him her hand then, and he lets her go with a very bad grace, and then Freda has nodded to them out of the window. He stands so long looking after her that Janet hails a hansom for her-self. She too feels too tired to talk to any one.

Through the West London streets with their hurrying crowds once more, rain and mud everywhere, and a gray sky. Poor Janet feels her already depressed spirits sink still lower as she drives along; it seems odd after three weeks of sunshine to miss it now. And then the lodgings are reached. She has paid cabby, and, carrying her bag, rings the bell. The untidy servant greets her with a tired smile. Miss Molly is still in bed, but she has said Miss Janet was to have breakfast at once. Janet puts down her heavy bag and mounts the stairs softly, and then she opens the door and sees Molly sitting up in bed, white and fragile. They are very undemonstrative, these two Scotch girls; so Janet only stands, saying, “O Molly!” with a catch in her breath, and then she kisses her sister softly, Molly holding her fast.

“How lovely to have you home again!”

There seems a good deal to do that day, and there is a great deal to tell. Molly, who has been very ill—though she will not own it—seems to revive under the descriptions of La Roche and the pine-woods, and she takes a great deal of interest in Mr. Bathurst; but Janet is alarmed at her evident weakness, and she feels as if the old burden of life presses heavily again.

Evening brings a well-known knock, and then she goes into the dingy parlour to find Hamish waiting for her with the gladdest of welcomes. Janet nestles into his encircling arms with a long breath, looking up, after a few moments of silence, with her rare sweet smile.

“Hamish, this is the happiest moment of it all. I did not know how much I missed you till I found you.”

“Janet, that is a very pretty thing to say,” he says, smoothing her hair. “And you are really looking better and brown—actually brown! London is full again—for me.”

She laughs, her face radiant as it never is except with Hamish.

“I have enjoyed every moment.”

And then they sit down on the horsehair sofa, and there are no happier people in all wide London than these two, for they forget everything for a moment but that they are together, and that they love each other. The divine alchemy of Love admits of no disturbing element.

“And I almost thought I was not going to see you again,” Hamish says, “there was so much about this Rood in your letters. Have you left him lamenting, Janet?”

Janet’s face clouds a little.

“We were all very sorry to part.”

“Miss Dunsterville too? “She did not bewitch him, eh, Janet?”

“She did not mean to. I don’t know if she did.”

And then they talk of other things, and she tells him of Mr. Bathurst till it is time for him to leave and for Molly’s medicine.

After this Janet takes up the old web of her life, and she is busier than ever. She teaches Molly’s children, and does two hours of writing besides in Molly’s room, for her sister picks up strength very slowly; and the merry month of June finds her so busy that she forgets to wonder why Freda has never come to see her. She has had one or two hasty notes, but Freda seems very busy and very full of engagements; and then she writes to say that she is starting unexpectedly for Scotland with her aunt, and will not see Janet till her return. Janet sighs a little, that is all. Their lives are so different, their fates so apart, and La Roche seems far in the past already. And Mr. Bathurst has been ill, and has been ordered to German baths, and he writes that he too will not be back till October. So the long hot summer passes with no event of note.

One day towards the end of October Janet has just taken up her pen, when the bell rings, and the little maid announces:

“A lady for you, miss.”

And then into the dingy room comes a dainty vision of velvet and furs, and Janet sees Freda’s face smiling at her from under a big “picture-hat.”

“O Janet, I am so glad to see you; and you must think me a wretch! But I’ve been away till yesterday; and you are as pale and thin as you wore before you went to the Ardennes. It seems centuries ago. And why has that old serpent Mr. Bathurst not carried you and Molly off?”

“He is only to come home this month.”

“I have been longing to see you,” Freda says, “Janet; I have such news for you, and I have so much to tell you. I am of age, you know, in December, and upon that I shall be my own mistress, and you and Molly must come and stop with me. I am going to take a little house in Mayfair, and have a chaperone till my marriage.”

“Till your marriage!”

Janet is so amazed that she starts to her feet, and Freda laughs gaily.

“I have gone and got engaged, Janet. O, I have all sorts of confessions to make. I was almost engaged before I went to the Ardennes, only D’Arcy and I quarrelled over les convenances and what we owed to Mrs. Grundy. I went to the Ardennes because he said I must not; but when I came back he gave in beautifully, and now he says I may do what I like. We are going to be the most independent couple in the world, and do each what we like. But I know D’Arcy will be proper all his life.”

Janet is looking at her almost unbelievingly. Then she says:

“D’Arcy Mandeville! And do you-love him?”

“Why, Janet!”

And then she bursts into a peal of laughter.

“You always wanted me to form a romantic attachment for poor Roland Rood. You know you did. My dear one, I have always liked D’Arcy best in all the world. That is why we quarrelled so. I could never have married any one else.”

“I never suspected it,” Janet says. “You always seemed to disagree on every subject, and to be so different. I wish I had known.”

“I could not tell you before,” Freda says, “for we quarrelled the very first day we got engaged. I am going to undo my furs, Janet; and will you give me a cup of tea? The carriage, with D’Arcy in it, is to come for me at six o’clock. And how is Hamish?”

Janet has risen to get the tea.

“He is pretty well. He suffers from dreadful headaches; his office hours are so long.”

“And the MSS.?”

“The usual ups and downs,” Janet answers; and then she goes off for the kettle, and Freda glances round the little bare room, with its flimsy mantel ornaments and its faded carpet.

She resolves that when she is married she will have both girls to stay with her, and give them the daintiest of rooms, and her heart smites her when she thinks of the settled gravity of Janet’s tired face.

She drinks her tea, tossing off her hat, and asking all sorts of questions, and she hardly notices that Janet is quieter than usual. By and by, Molly comes in, and Molly’s congratulations are much warmer. Molly thinks it a very suitable marriage, though she has no particular fancy for Freda’s fiancé. Still, he is rich and good-looking, and presumably the man of their friend’s choice.

When the carriage comes, Mr. Mandeville alights for a little, and he makes himself very pleasant to the girls. Freda treats him with the old laughing raillery, and she keeps the horses standing till he is extremely fidgety.

“My dear Freda, you have to dress, and dinner is at seven.”

“My toilet takes exactly ten minutes.”

“I wish mine did,” he retorts, and then turns to Janet, who is watching the complacent handsome face with rather sad and grave eyes. “She is as unreasonable as ever, Miss Janet.

While Mandeville is putting on his coat in the dark little lobby, Freda places her hand on her friend’s shoulder.

“What is it, Janet?”

“Did you hear from Mr. Rood?”

“Never.”

“I fancied perhaps you had.”

“Not a line. But he will bring the picture. You have not congratulated me yet, Janet? Come, wish me joy.”

“O, I do,” Janet cries; “you know I do. You will have all the world can give, Freda, and you have the love of the man you love. You are a very happy girl.”

Something in her voice seems to touch Freda, and she kisses the thin cheek very warmly, running off then to answer to Molly’s call, and then she is handed into the luxurious brougham, and they drive away.

Janet does not return to her MS. that evening. In fancy she is back in the Ardennes, and she sees again Rood’s grave face, with its kindly eyes, that seem to tell of the nature of the man so well- the simple, unselfish nature, with its reverence for all womanhood, and its reverence for all good.

“If I could only have warned him!” Janet thinks. “And O, if I only knew if he is thinking of her still!”

Freda’s visit has brought the Ardennes so vividly back to her that it does not seem to surprise her when next morning’s post brings a letter from Mr. Bathurst.

He is back in dirty noisy London, and the first thing Janet and her sister must do after receipt of the letter is to put on their bonnets and take a cab and come and see him; and then they must arrange about the visit.

As it is Saturday, the programme is carried out, and they make the journey by ‘bus and train. They find the old man. thinner, and he is certainly not looking so well as when at La Roche, but he is full of eager delight at seeing Janet once more, and he takes a great fancy to Molly. He sees in her a decided look of the little maid in the pink frock, and he will listen to and talk of nothing till they have both promised to give up the lodgings and come to him. He is so full of the project, and so masterful, that there is nothing to do but to give in.

The lodgings are given up, and next day a cab takes the girls and their modest belongings to the square, where the old man has two rooms prettily and brightly furnished for them; and then a new life seems to begin. Molly grows better day by day, perfect rest, good food, and complete freedom from care making a different creature of her; and Mr. Bathurst sternly prohibits more than two hours’ work a day on Janet’s part. Molly does the housekeeping, and they both accompany the old man on his daily drives, and Molly sings to him in the evening, generally winding up with “Barbara Allen” at his request.

And Hamish is not forgotten. He has been introduced, of course, and Mr. Bathurst likes the modest sub-editor extremely, and has said that after Christmas he is to give up his present employment and take work in the firm with which the old man is connected; and his post there will be a good deal better than his present one, and will increase in income yearly. In a year, Hamish thinks exultantly, he can take a little house, and he and Janet can begin life together. Sunshine seems everywhere.

So the months pass, and March is close at hand. Freda they see very often, and she is delighted at the course events have taken; and she is to be presented at the March Drawing-room, and in April she is to be married.

Meanwhile they have heard nothing at all of Rood.

CHAPTER VI.

It is a bitterly cold day in early March, and the crowds of people who have been hanging about Buckingham Palace Gate to see the Drawing-room débutantes have had their features sharpened and chilled by an east wind which penetrates through the thickest wraps. It is a day to chill the ardour of the most eager aspirant for the honour of kissing the Queen’s hand; and as for the poor dowagers, every feature of their faces seems to say, “O that this were over, and home and tea was reached!” Everything seems chilled- the poor pretty faces under their nodding plumes, the men on the carriage boxes- even the waxen petals in the gorgeous bouquets, and one and all seem to breathe again when the carriages are re-entered, and the welcome word “Home” given to the coachman.

In one luxurious carriage Freda and her aunt Fanny are leaning back, Lady Sanley with a sigh of relief. Freda laughs as she pats her hand.

“Poor Auntie! But it is over.”

“My dear, I never saw such a crush.”

When they reach Mayfair, she runs lightly into the house and up-stairs into the drawing-room, where there is a blazing fire, round which several ladies are waiting. They gather round Freda and her aunt, and she is admired and made to stand in this and that attitude, till she rebels at last, and they bring her tea and muffin in a quiet corner.

Meanwhile, as the chill afternoon closes in, a man is walking towards Mayfair, his coat closely buttoned up, and his thin face full of an eager but repressed impatience.

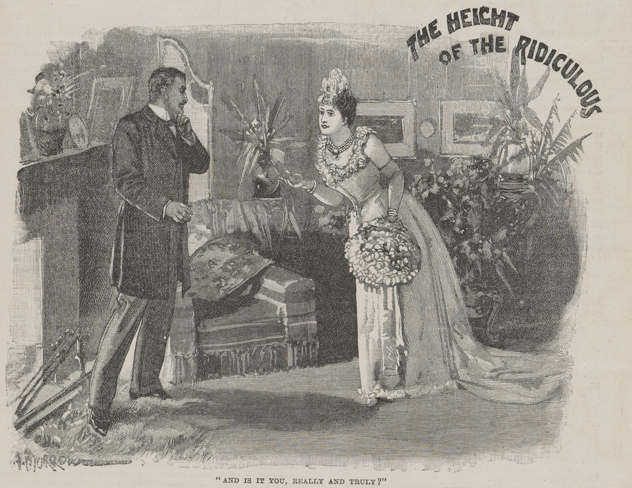

As he nears the house he breathes rapidly, and his eyes shine; he can think of nothing but that- that he will touch her hand, look upon her face, hear her voice! Beyond this he dare not go. He rings the bell, and is shown into a little room on the left, which is full of flowers and girlish prettinesses, and which is only lit by the fire’s glow. He stands on the hearth-rug, his head bent and his hands clasped, and presently the door opens.

“And is it really you? Really and truly?”

He looks up, and sees a vision of loveliness in a white satin dress, that catches all the fire’s glow, her golden hair dressed in shining curls and braids, and with diamonds amongst the lace at her neck; he stares as if bewildered, and then Freda has held out her hand, and is laughing in his face.

“You are wondering at this attire on a March afternoon? It is my Court dress. I have just been presented.”

“Yes?” he says lamely.” I could not understand at first,” and then he half laughs. “You look like a bride.”

Freda smiles.

“And you have really come! And my picture?”

“I have brought it. It is at a friend’s house.”

She clasps her hands delightedly.

“And is it a success?”

“They say so. It is like you.”

“And what are you going to do with it?’

“You shall say,” he says slowly; and then she motions him to a seat, and rings for tea to be brought there.

“But you are not looking well, Mr. Rood, and I feel guilty. I remember Janet saying you ought not to paint, you said it made you ill.”

“It was my happiness. I am not ill.”

“You must take a rest now. And when may we come to see my picture?”

“To-morrow afternoon. Will that suit you?”

“Perfectly. And may I bring my aunt and Janet, and another friend? Janet will be so charmed to see you, and I want to introduce the friend.”

She has given him her hand again, and he hardly hears what she says. He is looking into her face with his haggard eyes, and he tells himself she is fairer and brighter than gold; and the little hand rests in his so confidently; she is looking at him very kindly; there is a new softness, too, in her face, he thinks; and then she drops her hand, and has promised to come, and she opens the door for him herself, and stands talking till the last moment.

Rood goes away so happy that he seems to walk on air. She has met him more kindly and more joyfully than he has dared to hope; he remembers every look, every tone; and she has expected him to write, and has talked of him to Janet. These things are all he thinks of as he walks home.

CHAPTER VII.

Rood has been in the studio since one o’clock. The picture is placed where it can catch the last light; but he does not look at it at all: he has been pacing the room backwards and forwards ever since three o’clock, and he does not stop till the roll of wheels makes him look out of the window.

He is at the door to receive them, and Freda introduces her aunt and “Mr. Mandeville,” Janet greeting the artist with unusual warmth. She looks at him anxiously, but his face is bright now, and his eyes shine, and she thinks he seems better than she had hoped. He talks rapidly, too, and seems quite at ease. Mandeville finds him not quite what he expected, and they all approach the canvas eagerly. Freda is standing before it already, her face all aglow with delight, her hands clasped, and now Rood only looks at her. Her evident admiration brightens his face still more.

“It is wonderful!” she cries; “O, it is beautiful! Can’t you breathe the hot air? I feel the pine-needles warm under my hand. O Mr. Rood, you are a magician! I am back in La Roche.”

She turns round to him, her eyes shining, her lips parted in a gay smile, and she suddenly holds out her hand.

“How did you do it? You have succeeded. This must win you fame. O I am sure of that!”

She has taken a few steps up to where he stands, and as Mandeville moves then, to see the picture better, they are practically unseen. Only Janet, turning round with a sudden startled glance, sees the expression of his face, and she trembles. Hope- a blaze of hope- has leapt into his eyes; he looks young and handsome with that glad expression of triumph; one forgets the thin features and the hair, gray above the temples; and then he takes her hand and bends above it, speaking very low.

“You think I have won fame?”

“O, surely! And you will send the picture to the Academy? How proud I shall be! I feel as if I had a little share in it.”

The light seems to grow brighter in his face, for Freda has for-gotten everything in her excited admiration, and her eyes sparkle and shine.

“Proud!” he repeats; “proud!” and then he stops and looks at her hungrily.

His lips seem to move, but he does not say more.

“I said you would win the victory at last,” Freda cries, and then she turns round. “D’Arcy, come and thank Mr. Rood for making me famous.”

Mandeville comes as desired, and Rood starts and looks up as they stand opposite each other- a contrast, Janet thinks; the complacent self-satisfaction of the one handsome face, the eager struggling hope in the other. And her heart is beating fast.

“Why should he thank me?” Rood enquires then, smiling at Freda. “I need no thanks. I worked for art, and to make the picture worthy of you; I need no thanks from any one.”

He speaks gently and with perfect respect, but Mandeville straightens himself up.

“When the picture appears on the line- I am sure it will be on the line-” He says, “Miss Duntsterville will be my wife, and I am naturally interested in its success.”

“Your wife?”

There has been a silence, but he speaks very quietly, though it is as if a light, when Janet sees his face, were suddenly quenched behind a lattice; and then he looks from Mandeville very slowly, and his glance travels till it falls upon Freda’s blushing face, and his gaze rests there.

“I did not know this,” he says slowly; “I did not know.”

Mandeville notices nothing in either manner or voice, and he moves back to the picture, for the light is fading; Rood is left looking before him heavily, and then Freda speaks, and he starts:

“I am to be married next month, Mr. Rood. I hope you will be here, and will come.”

“I do not think I shall be here, thank you.”

“But you must wait to see the success of your picture,” she cries.

“O, you must wait! Must he not, Janet?”

Janet comes up then, and her dark eyes rest upon the artist’s weary face. It looks suddenly as if it had grown tired and old.

“Mr. Rood knows best,” she says. “The picture will be a success. It is beautiful; but as to his staying, he knows best. All people do not like London.”

“Famous people do,” Freda persists, and then the entrance of a servant with candles and the tea-tray prevents any further discussion. Janet is giving the picture a last look, and Rood and Freda are left alone at the door. She has fastened her furs, and now holds out her hand.

“You will come and see me very soon?”

“No,” he says slowly. “I only came to bring you my work, and now I must go back. I am glad you are pleased. I am glad you think it is a success.”

“But you?” she says impatiently. “You don’t seem to care! What is it, my being pleased? You must know that you have succeeded, and are you not glad?”

He does not answer; she thinks he does not seem to hear. Janet, listening in spite of herself, hears a long breath.

“Fame is a curious thing,” he says; “a curiously worthless thing.”

“Worthless?”

“Yes,” and there is almost a wall in his voice. “We strive for it, and would barter life and soul for it, and then it turns to dust and ashes in our grasp. Or perhaps what we hope it would buy cannot be bought. God’s gifts cannot be bought; they are of His good pleasure.”

“I do not understand,” Freda says. “Why do you look so grave? I have not vexed you?”

“You? O no,” and he laughs, and then suddenly looks down at the bright face under its leathery plumes, and his expression changes. He looks at her very gently and kindly. “I do not think that you and I will see each other again, Miss Freda, and I have never wished you joy. I do wish you joy- better than that, God’s peace. And may I say something to you?”

“O yes, anything!”

“Do not hold the world or what the world can give too dearly,” he says; “hold this life as lightly as you can! Never set all your life’s work and all your life’s desire on one thing. Never do that. God bless you always.”

She is very far from understanding, though his words astonish and annoy her vaguely, and then she holds out her hand, and he takes it.

“Good-bye.”

Somehow she cannot think of anything else to say, and he repeats “Good-bye” very slowly and tenderly. And then Freda is gone. When she reaches the foot of the stairs Janet has followed her, and Janet touches her arm.

“They are waiting in the carriage, Freda; go on without me. I have a message for Mr. Rood from Mr. Bathurst.”

“Very well,” Freda says.”Poor fellow, he does look so ill! And wasn’t he funny, Janet, telling me to hold the world lightly? But what a good man he is! And I do wish I could make him happy and rich! I wish I could do something for him. How will you get home?”

“I shall take a hansom,” and then she mounts the stairs slowly, and the carriage drives off. For Janet thinks she cannot leave that solitary figure in the darkening room with no word of farewell.

Rood has blown out the candles by the tea-table, but he has taken one in his hand, and he is standing now before the picture. When Janet comes in softly the expression in his white face surprises her. Somehow the great restlessness seems to have left it, and all the sharp hunger.

“Mr. Rood,” she begins, and then stops; he is so white and worn, and pity is so strong in her heart that tears fill her eyes. She stretches out her hands instinctively, looking at him with tender womanly sympathy.

“O, I am so sorry,” she whispers; “I am so sorry!”

He takes the kind hand, and then puts down the candle, and they stand before the canvas, and a little disc of candle-light seems to fall upon the bright merry face, leaving all else in shadow.

“It is very kind of you to be sorry, Miss Janet,” he says slowly, letting her hand fall. “But when we dream foolishly, we cannot expect to see our dreams realised. You saw my dream. No one else ever will. I have been restless and unhappy all these months. It seems to me as if I defied God, as if I said ‘I shall win fame, I shall win her, I must have this joy!’ I did not ask His help or guidance. And now He has said to me very gently that my will was not His.”

The tears fill Janet’s eyes.

“I wish I could have told you; I did not know till autumn.”

His hands fall, his head sinks on his breast, a long, long sigh escapes him, and Janet hears a sound that is like a moan.

“O Heaven, help me!” he whispers. “Heaven pity me!”

For one moment the anguish of loss sweeps over him. Janet bursts into tears then, and he starts and looks at her.

“Miss Janet, do not-”

“It is so sad. I am so sorry—so very, very sorry!”

“How kind you are! Miss Janet, do not cry, I cannot bear to see you.”

“Love is a dreadful thing,” poor Janet cries; “it is a dreadful thing. It upsets all the world; it is a pain and a misery!”

He looks at her gravely, with a sad smile.

“That is only one side of the picture—only one side. Love will turn a smiling face to her, Miss Janet, and to you, please God. And I do not believe that any love is ever wasted in this world.”

He puts her into a hansom, and then they shake hands- a long, close hand-pressure. The old ache of pity seems to fill Janet’s heart as she looks into the tired white face, and she notices with a sting of painful memory that his coat is new. Freda could not laugh at it any more now. And something seems to tell her that this is good-bye.

“Will you write to me sometimes?”

“If you care for it.”

He has smiled almost in the old way.

“Good-bye, Miss Janet,” he says; and then the hansom has started, and she is soon whirled away. Rood is left standing on the pavement, looking after her; and then, turning, he marches away through a maze of streets, and it is late before he returns to Fulham Road.

“Then he has not sent it to the Academy. What an extraordinary man!”

“He has sent it to me,” Freda says. “I shall send it to the Academy in his name. But as to how I shall manage to give him anything in return, I must consult Janet. He is as desperately proud as she is, so she may be able to suggest something. Mr. Seay brought Ainslie the art-critic to see it yesterday, and he was perfectly charmed. You should have heard him! He said it was full of le plein air; that the artist had found a secret that had puzzled and was puzzling them all. He wanted to rush off and find Mr. Rood at once. You see, I was right about my genius. Mr. Ainslie said it would be one of the pictures of the year; and he brought an old German from Munich, who stood and snapped his fingers over it in a state of delight. And the odd thing was that he knew Mr. Rood. He said a very funny thing. I asked Mr. Ainslie to translate it to me. He said that he always knew Rood could paint one thing that would astonish the art world; but that he did not believe he could do more, and he had doubted if he would have strength for the one.”

Janet pauses, and for a moment she looks at the picture without saying anything.

“It is a very handsome wedding-gift.”

And the wedding takes place in due time, and goes off with immense éclat. There is a Bishop, and there are present a great many fashionable people, and Freda looks lovely. And she is radiantly happy. She thinks of what Rood has said to her, about holding the world lightly, with a little smile on her wedding-day. It is such a beautiful world; who could hold it lightly?

CHAPTER VIII.

AND LAST.

Three years later the brilliant beams of a May sun are flooding the stately square of Burlington House and all the handsome equipages waiting there for their occupants. Freda Mandeville has just descended from one, and she makes her way up the staircase.

Her own dainty costume and sweet face are a good deal com-mented on, as she sits, glancing around her, and pushing the end of her silk sunshade absently into the carpet. “Pretty Mrs. Mandeville” is a well-known figure in society.

While she is sitting there a lady comes up to her.

“Is it really you, Janet?” Freda says.

“Why, Freda! And it is ages since I saw you!”

“I believe it is eighteen months,” Freda says reproachfully. “How long have you been back?”

“Molly and Mr. Bathurst are still abroad,” Janet says. “And we only got home last week. Hamish came to fetch me. He could not do without me any longer. And Mr. Bathurst is much better.”

“Where are they, Janet?”

“In Holland just now. Did you get my letter from there, Freda?”

“No. Did you send it to the square? We have left that house.”

Her face changes as she speaks. It has grown more womanly, Janet thinks, looking at her earnestly, as they walk to the sculpture-room and sit down; and she fancies there is a slight shadow over the old brightness- a little of Freda’s sparkle is gone.

“Janet, you think I have neglected you; I know you do.”

“No, dear,” and Janet speaks in the old direct way; “but I know our lives were very different. You and Mr. Mandeville were gay rich people, and Hamish and I were beginning very humbly; and you were very much engaged and run after, and your life was very full.”

“My life is not full now,” Freda says, her eyes growing hungry for a moment; “and I had everything.”

Her face shadows as she speaks, and she resumes restlessly:

“He likes me to go about as usual, and be admired, and dress well, and receive. Who was it who once warned me to hold the world lightly? Ah, I remember; it was Mr. Rood.”

“You know about him?”

“No; what?”

“He is dead,” Janet says. “Molly and Mr. Bathurst went to see him two months ago, and they found him in Antwerp. They said he was looking much the same. He was very kind, and showed them everything and took them everywhere. People told them there that he did so much good in a quiet way, that there was no one in all Antwerp so looked up to and loved amongst the poor. The priests used to go to him for advice and help; he had won over people they had failed with, and they all liked and trusted him, though he was a heretic. They said he did not try to make converts; he only did good. There was a great deal of typhoid in a bad part of town, and he had been giving his money away, and had got into a low state of health; and of course he worked hard. He took the fever, and sank under it. They said it was not a bad attack, but he had no strength to rally under it. An old priest wrote to Mr. Bathurst and told him all about it. And all Mr. Rood’s effects were to be sold, and the money to lie in trust for the poor- all except the little canvas he painted of you in La Roche, Freda, from which he did the large picture; he left that to me.”

“And I never repaid him in any way,” Freda says remorsefully; “I never even wrote again after he did not answer my letters telling him of the picture’s success. Perhaps he never got them. What a sad story, Janet; what a sad death!”

“I think it must have been a beautiful death,” Janet says. “Peace is better than happiness. He was at peace with all the world.”

“Those happy days of La Roche are gone, Janet dear,” she says after a pause.

“Yes. He is dead, and you are a London lady, very rich and very happy, I hope, dear Freda; and Hamish and I are as happy as two people can be who live in this workaday world. It is a good world, after all, Mr. Rood used to say.”

“It is a very go-ahead one,” Freda says mournfully, rising and taking her sunshade, and the softness of memory leaves her face a little. “I must go and look for Lady Lassaile, and we are to meet D’Arcy in Bond Street, and I have two balls on hand to-night, Janet. Good-bye, dear. Come and see me, Janet. Keep me fresh, and make me believe in goodness and in simplicity, as Mr. Rood used to do. Somehow I keep remembering things he said to me, though I don’t know that I think of him. And I feel better for having known him; the world seems a better place, somehow, when I remember him.”

Janet’s dark eyes shine. She wishes, with a little curious irrelevancy of thought, that the dead could hear.

And then she and Freda part, and Janet goes back to her happy home; and when she tells Hamish of her meeting with Freda that night, she winds up with this conclusion:

“And after all, Hamish, I believe that what seem the saddest things in life are really the happiest. No good life, no good thing, ever dies.”

“I don’t quite see what you mean, my dear.”

“No,” Janet says; and then she sighs.”But you do not know the story.”

THE END.

Word Count: 17226

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Kaylie Duckworth

Katie Sanofsky

Sarah Burlett

Ainsley Dinger

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

11 March 2025

Last modified

3 February 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Ardennes: a forest region primarily in Belgium, but extends into parts of Germany and France. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mrs. Grundy is a well-known English fictional character who often represents the censorship enacted in everyday life by conventional opinion. She first appears in the 1798 play, Speed the Plough. |

| ↑3 | Sicht for saier een: “a sight for sore eyes” in the Doric Scottish dialect. |

| ↑4 | Dégagée: French for “clear.” |

| ↑5 | Hawes Craven was an English scene painter. |

| ↑6 | Table d’hôte: French for “Host’s menu.” |

| ↑7 | Salle des chevalier: French for “Hall of the Knights.” |

| ↑8 | Ourthe: a river in Belgium. |

| ↑9 | La Roche: A City in Belgium, translates to “The Rock.” |

| ↑10 | Salle-à-manger: French for “dining room.” |

| ↑11 | Déjeuner est pret: French for “lunch is Ready!” |

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.