The Other Side of the World, Part 1

The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 3, issue 101 (1882)

Pages 145-148

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: Written by Isabella Fyvie Mayo, someone we would now consider a feminist writer, “The Other Side of the World” features two young women who are desperate for adventure and freedom to choose their own fates. Written during a time when women didn’t have many career options, this story follows two young women who travel from England to Australia in pursuit of a new life, one where they can be successful. Originally printed in The Girl’s Own Paper, the story was geared towards young girls forging their own paths into adulthood. It features adventure, romance, friendship, and inspiration for young women.

Advisory: This story includes ableist slurs.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the first of three parts:

“In all the wide world I wonder if there is a place where we are really wanted?”

It was a sad speech for a girl of nineteen to make to another of twenty. But perhaps there are few, either men or women, whose hearts have not known that bitterness at some time or other, though it is oftenest on the lips of those who do not make themselves very desirable blessings. She who uttered the cry now might easily be forgiven for doing so. For when one has been fatherless and motherless nearly all one’s life, and has passed from orphan-school to teaching in a boarding-school, and has for the last three months looked daily through three newspapers’ advertisements of situations vacant, and written upwards of fifty “answers” thereto, all fruitless, it is small wonder if one feels disheartened and even despairing.

The elder girl, Bell Aubrey, did not answer for a few minutes. She had had a life-history very different from that of Annie Steele. For Bell Aubrey was the third daughter in a family of eleven; and in the house of her father—a country surgeon—there had always been joy and love, and simple plenty in her younger days. It was only of late that the burden of life had begun to press upon Bell. One of her elder sisters was an invalid; the “boys” had got to be started in life, and five of the younger children had still to be educated. Papa was growing careworn, and mamma’s eyes often filled with tears. “We girls must be doing something,” Bell had thought. “I must begin. But for what am I fit?”

That was a serious question. It was in a secret hope to find its answer that Bell Aubrey had gone to pay a long visit to the Misses Brand, distant connections of her mother’s, who kept a girls’ boarding-school. One of the Misses Brand had been indisposed, and Bell undertook some of her duties, while Annie Steele was temporarily engaged to fulfil the rest.

But Miss Brand was now convalescent, and so Annie Steele’s engagement was drawing to an end, and Bell Aubrey would be free to return home. And instead of having found an answer to her question, all the progress the poor girl had made was the discovering what a very perplexing question it was.

She had never hoped that she might be a governess, for she had no accomplishments; but she had had a thorough English education, and she had thought she might be a school teacher. Now she knew that she did not like teaching, and did not teach well—that by the time lessons were over she had not cleared her pupils’ brains, but had only confused her own.

“It is dishonest to try to get a living by doing what one cannot do well,” mused straightforward Bell; “and, besides, here is poor Annie, who loves to teach, and yet can get no engagement.”

But when Bell heard Annie’s despairing cry, she felt “this would never do.”

“Of course, there is a place for us,” she said, cheerfully. “We may be quite sure of that. All we have to do is to find it, only that seems the difficult thing.”

“Those dreadful letters!” wailed the poor little teacher. “After paying all my necessary expenses here, every penny that I might have saved from my salary has gone on stationery, and postages, and advertisements. And what an investment it has been! You know the answers I have got! Nearly all of them from school agencies, telling me what a large connection they have, and advising me to register at once, and then, as soon as I have paid my fee, writing back that there is nothing on their books at present to suit me, but that they will let me know when there is. And two or three from people at the other end of the kingdom, offering me sixteen pounds a year to teach everything to six children. And then that terrible letter, Bell! That has done me more harm than anything, because it has frightened me. I always knew there were wicked people in the world, seeking to lead others astray, but I never realised that they were so near us. I feel like a poor lost sheep in a wood, with wolves dogging it behind every tree!”

“Poor little Annie!” said Bell, soothingly. “l am so sorry you burned that letter after you showed it to me, for I would have sent it to papa, and he would have given it to the police, and the wicked people who sent it might have been punished, or at least disturbed in their wickedness.”

“Oh, I could not help burning it!” cried Annie. “It seemed a disgrace to have had such a letter sent to one. And then, Bell, even if I do get a situation, I shall never be able to save money, not so much because the salaries are low, as because the situations are so uncertain; and when one is obliged to leave, one is sure to have to wait weeks and weeks for another, and spend all one has on board and travelling expenses. It may be very well for girls who have friends.”

“No,” said Bell, with decision; “it is not well for girls who have friends, for girls who are doing work in the world should be able to help their friends rather than be driven to prey on them. I’m not at all sure whether it is not the way in which girls are content to be propped up, and to think they may shuffle along anyhow, in hopes they may get married at last, which has made things so hard for working women.”

“But most women do get married, of course,” said Annie, “especially girls with happy homes and circles of friends.”

“Yes, certainly,” said Bell. “But don’t you think there is something wrong in the way in which girls will spend their lives doing fancy work to earn a few shillings for finery, spoiling their health, and learning nothing which will be of any use to them afterwards, instead of dismissing the servant and doing their own housework, leaving crewels and so forth to those who have no servant to dismiss, and who, being too poor to save, are obliged to earn?”1Crewels are embroidery using wool.

“But if many girls did that, what would become of the servants?” asked Annie.

“There are plenty of places for them,” said Bell. “ If you knew all I know of domestic service, you would understand that it would be a real blessing to them to find that they could not get work unless they were really honest, capable, and respectable. Besides, they are wanted everywhere. They are the only people which are too scarce in England. And they are the very people who are always welcome in the colonies.”

“I wonder if there is a corner in the colonies for me!” sighed Annie.

“I have wondered that, too,” said Bell. “And the other day I saw in the papers an announcement about a women’s emigration society.”

“How you have thought over these things!” exclaimed Annie.

“And it is quite time,” said Bell, gravely. “I must be as self-dependent as you. At our house we keep no servant; my mother and sisters do everything; and they have managed perfectly without me for these four months. We can save no more at home, and yet it is not enough. I must not think of going home again. Your experience has convinced me of the uselessness of advertising for teaching appointments. Annie,” she added, suddenly, “suppose we write to this emigration society, and see what they can offer us?”

Annie caught her friend’s arm in a tight clasp. Her grave face was lit up. A breath of hope and adventure was wafted over her Sisyphus-like life.2A character of Greek Mythology, doomed to roll a rock up a hill for eternity.

“We can, at least, see what they say,” she cried. “But your people will never let you go abroad, Bell.”

“ Yes, they will,” said Bell; “if the circumstances are such as to make it right and fit for you to go, they will let me go. My father is a wise man; he and I have had many talks over these matters.”

And so a letter was despatched to the Secretary of the Women’s Emigration Society. The girls kept that a secret. “It will be time enough to tell anybody when we see what answer we get,” said Bell. And while they waited they went about their work with a delightful feeling of enterprise and elation.

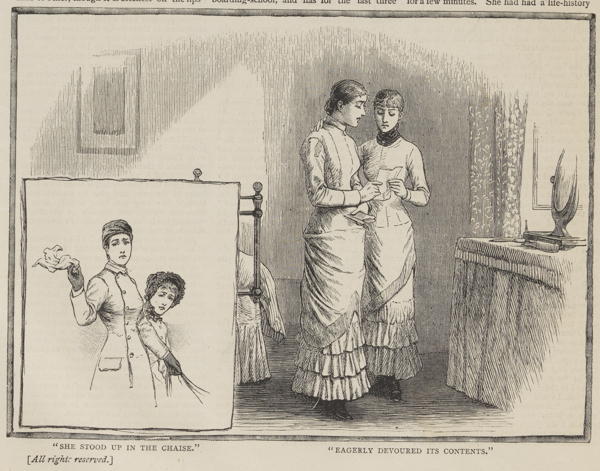

Two or three days brought back a little packet of circulars. Annie Steele knew what it was when the servant laid it down beside Bell’s breakfast-plate, and Bell put it into her pocket unopened. Both the girls sought their bed-chamber at the earliest opportunity, and eagerly devoured its contents.

First came a statement of a public meeting at which the objects of the society were discussed. Among the people present were good and great men in many walks of life, ladies of rank, and influential colonists perfectly familiar with the subject. Attention was drawn to the fact that emigration is almost given over to men, thereby leaving an undue number of women in the mother country deprived of their natural duties and employments, whether domestic or industrial.

“People will say we go to look for husbands,” murmured Annie.

“Never mind what they say,” said brave Bell.

At this meeting it was further said that to the objection often raised in England by women upon whom emigration was urged, “How can I leave all dear to me?” it might be replied that there is hardly a family in the highest class the members of which do not travel and settle in different parts of the world, and that surely, then, other classes may do the same.

Another question, “How can a young woman take her passage in a merchant ship to find her way to a distant colony?” the Women’s Emigration Society was intended to answer, as all preliminary arrangements, together with adequate provision for the safe transport and reception of emigrants, were now made by it.

Then a distinguished statesman said that he supposed there was no parish in the United Kingdom which had not already sent its contingent to the colonies, and that the class of educated women is perhaps the only one which is not represented in them. He dwelt upon the excellent arrangements made for the transport of emigrants of all ranks, and the almost paternal care which many of the captains show to those under their charge.

Then a colonial bishop rose and remarked that when he first went to his work in the southern hemisphere he found that the greatest want of the colony was the presence of women of a class superior to those hitherto sent out by the ordinary mode of emigration, and wherever he went he found the need growing still greater.

Another bishop from a northern colony dwelt on the importance of a careful selection of the emigrants, and of providing them with specific recommendations to employers in the colonies. He said that in his diocese there were Young Women’s Christian Associations, who made it their business to welcome persons from England, and to secure situations for them; and that there is ample room for a large influx of servants, and also for women, who, though they may not have actually been in domestic service, are capable of practically assisting the ladies of the family in cooking and household matters.

And the account concluded with a statement of the number of women who had already gone out under the auspices of the society during the first year of its working, and who were now doing well at their respective destinations.

“I think it will do,” said Bell Aubrey, though at that moment there rose before her mind’s eye a vision of the old house at home, and the merry children shouting and playing among the ancient hedges of the roomy garden. And it did seem so hard to have to go away. But she said nothing. Why should she cry out, because it was now her duty to give up what Annie Steele had never had?

“I shall write one more letter to the society before I tell father,” she said. “I shall write and ask what it costs to get to the respective colonies—in short, the step which should be taken next by young women in our present positions, if desirous of emigration. You see, Annie, we are as yet only seeking full information; when we have obtained that, it will be the right time to ask for counsel and consent.”

Then followed a few days more of patient waiting, and then came a little packet enclosed in the prepaid book-wrapper which Bell had sent to the secretary along with the modest request.

The first paper the girls unfolded was a large sheet, which set forth on its front page the principles on which the Women’s Emigration Society work. It stated its functions as— (1st) “Collecting and distributing information from reliable sources respecting each colony; its climate, resources, &c.; (2nd) arranging for the comfort and safety of emigrants during transit to those colonies, for which their circumstances appear to render them most suitable; (3rd) establishing relations with trustworthy persons at each port, who shall pledge themselves to receive and befriend the emigrants accredited to them by the society; and (4th) raising and administering a fund for the purpose of assisting, after due and careful investigation, the emigration of suitable women of sound health and good character, who are unable to raise the sum required for the purpose, such assistance taking the form of a loan, for which security is required and interest expected.”

As Annie Steele read the last words her brightened countenance clouded.

“It may do for you, Bell,” she said, “but I have no money of my own, and who would be security for me, even if I cared to start in life under a load of debt?”

“But stop a minute,” said Bell, turning over the page. “Listen to this.” And she read—

“Free or assisted emigration is still open to most of the colonies for young single women who will register themselves. The women must be of good character, and willing to perform domestic service, as the agents in England are responsible to the colonial authorities for the class of emigrants they send out; but, of course, many of them are very rough. The accommodation is divided into compartments containing eight or ten berths, with a separate mess for each party. The present regulations in emigrant vessels removed all the real dangers to which single women were formerly exposed when on board ship. The best or saloon end of the vessel is set apart for them, and they are not allowed to quit it. A well qualified matron is put in charge of them; they are under strict rules and discipline as to leaving their berths, taking the air on deck, &c.”

‘‘There!” said Bell, “I should be able to ‘register,’ as they call it, for domestic work is exactly the work I want to do. You are a governess, Annie, and wish to be a governess wherever you go; but if you are willing to take a situation as a nurse or a sewing maid till better chances offered, I have no doubt you will be allowed to register, too.”

“But I don’t believe your father will allow you to go in that fashion,” suggested Annie.

“I think I might persuade him,” returned Bell. “Look at the cost of the paid passages,” she said, running her finger down the next page, below items varying from eight guineas to twenty-six. “If I can once prove to father that there is no hardship or roughness which any good girl need fear, I think he may yield. To put up with a few privations, such as the families of the Mayflower pilgrims and of all other pioneers must have encountered, is not a bad way of earning such a sum of money as that.”

The other papers were simply a detailed report of work already done by the society, and a schedule to be filled up by intending applicants for its assistance.

“I shall write to father at once now,” said Bell, looking up from the papers with a set, steady face.

“It will all end in nothing,” sighed Annie Steele. “Your people will never consent, and I shall be afraid to go alone, and shall have to go back to my hopeless advertisements and my Tantalus successes.”3Tantalus was cursed to never be able to drink or eat after offending the Gods in Greek Mythology.

“I shall go home in a fortnight from this time,” said Bell, not heeding Annie’s sorrowing tones. “But I shall write and tell father all about it while I am here. I think it may be easier for him and mother to consider it all calmly while I am out of sight. I shall tell them you want to go too, Annie. There has always been a great deal about you in my letters home. They say they seem to know you quite well.”

There were some people who said that Bell Aubrey had a secret for getting her own way. Perhaps Bell had a knack of convincing people that her ways were likely to be right. Perhaps one of Bell’s secrets was that she always stated her case temperately, making due reservations for the exercise of lawful authority or of wisdom greater than her own; also, that she looked facts in the face, and admitted the existence of unfavourable ones, even while she brought forward others which seemed to her to outweigh them.

She wrote how she found she did not like teaching, and how many women were contending for every post that was to be had. Then she narrated her impulse towards emigration, and enclosed the papers with which she backed it up. Next, she spoke of Annie Steele’s friendlessness and poverty. Emigration was doubly desirable for Annie, yet Annie could not emigrate, except she went in the humblest way. And if that could be right and safe for Annie, it could not be wrong or dangerous for her. For if she went, they might indeed spare the money to pay her passage, but they could only do so by deducting something from money already needed for the other children. Did not they know that she would work very hard, that her brother next in age might get the drawing-lessons he coveted so eagerly, and which might set free a real gift struggling within him, and so elevate and brighten all his life—for that matter, all their lives? If they thought she had a right to this passage-money, let them allow her to save it in this way, and give it to him instead. And that would also enable her to do Annie the service of accompanying her. And they knew she always delighted in adventure!

It was two days before Dr. Aubrey’s answer came.

“Dear Bell,” he wrote, “you have made us very sorry—and very glad. We are very sorry to think of parting from you, and very glad to feel that one of our daughters is proving herself to be a brave, true woman—a working bee and not a destroying moth. I cannot go into all your arguments now, and must think over them much longer and get much more information upon the matter before I can give them any answer worthy of them. You will not wonder that the thought of the first child’s going away, and going so far, touched your mother to the quick. She cried out that when one of a family takes flight, more are sure to follow the lead! But after the first pain was over, she realised fully that we cannot keep you all at home, and then she thanked God, through her tears, that the lead you were giving was so good and so unselfish. And when your poor lame sister said, ‘What could we do without Bell?’ your mother actually said, ‘I can see even that is a happier question than the other, ‘What can we do with her?’ which so many households have to ask about their daughters. All I shall say now is, that we cordially invite Miss Steele to accompany you on your return home, and then we can all think over the whole matter together, and at leisure.”

And Annie Steele thought within herself, “They will let her go after all. They have invited me there that they may know the companion Bell is to have, and so be able to make a better picture of her in their minds when she is away.”

As under no circumstances were either of the girls to return to the Misses Brands’ school, they packed up all their little belongings to take with them to Dr. Aubrey’s. The good governesses rather wondered that Annie Steele going away for a short holiday, and with no engagement in view, could be so excited and elate. Just at the very last, Annie confided their secret to them, and found that they were aghast at its bare idea. They almost frightened Annie by the picture of horrors which they conjured up. It needed all Bell’s calm philosophy to restore her courage; most of all, it needed Bell’s reassuring, “We will see what father says.” It is only very foolish young people who chafe at authority; the wiser sort know that it does not impose a fetter, but grants true and safe freedom.

Beyond a very few words on the night of the girl’s arrival at the old green-clad house in the country, nothing was said on the subject of emigration for some days. At least, nothing was said in the general household. It is quite true that more than once Dr. Aubrey took Bell to drive with him in his rounds among his patients. Perhaps it was then that Bell reiterated her telling arguments.

“If it is not right and safe for me to go out in this way, then it cannot be right and safe for an orphan like Annie Steele. If there is nothing worse than hardship and privation, then I must be a poor creature if I cannot endure them that I may spare you so much money. Father, let me go. I shall be able to send you home word if there are any openings out there for my younger brothers, and if they should go out, you would not feel so anxious about them, if I, quite an experienced colonist, was there to receive them.”

During those early days, too, the Doctor was taking great note of Annie Steele.

“She is such a fragile-looking thing,” his wife said. “Though Bell is our own daughter, and I am likely to be fanciful and tender over her, I should say she is twenty times more fit for hard work and for roughing it than is this poor little fairy.”

Annie was made free of the kitchen, and she expressed delight in no measured terms for what was a real blessing to one who had spent her life in schoolrooms and drawingrooms. Annie was made free of the garden, and could race and romp with the children without fear of compromising tutorial dignity. It was a little difficult for her to see children in any light but that of “pupils,” but a few days’ experience of the young Aubreys made it easier. Annie’s voice began to ring out in merry laughter. The roses began to bloom on Annie’s cheeks.

“She’s healthy enough,” said the Doctor, who was a great gardener. “She has only been potted too long. She wanted planting out. Give her plenty of active work and a due share of hope and joy, and she has as good a chance of reaching a hundred years as most of us.”

It was hard to tell when “out there” gradually changed to the more definite locality of Queensland. For one thing, the society, when applied to, recommended this colony. For another, the Doctor thought its climate would suit Bell, and would be decidedly wholesome for Annie. So they got the schedule for “applicants,” and with a little pathetic merriment they wrote out answers to questions as to age and condition, health, religion, and capabilities, and stated their determination to accept the free passage offered to any who could describe themselves as “domestic servants.” There was a little debate as to how this could be done honestly in Annie’s case, since she wished ultimately to find employment as a governess; but as she was quite ready to engage as a sewing woman or to give assistance in any domestic duty within her strength, that difficulty was soon got over. For Bell there was no difficulty. She could simply describe herself as a “daughter at home,” who had done household service in a school, and was prepared to do it again, wherever she could find it. References as to character were, of course, easily obtained by both the girls, and each got a favourable medical certificate. These formalities being finally gone through, they were warned to hold themselves in readiness to sail in a fortnight’s time, which would be about the end of March.

There was not very much time to be sad: there was so much preparation to make. Mrs. Aubrey and her elder daughters winced a little when Bell received the “Regulations for Female Emigrants.” They brought before them so plainly that their bonnie pet was going to seek her fortune as a simple working woman. But Bell did not wince; she said there was some comfort in seeing that female necessities in the way of garments could be reduced to the bald list of “the lowest quantity that can be admitted”—to wit, “six shifts, two warm and strong flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of strong shoes, two strong gowns—one of which must be warm.” She was not sure whether life, even if really reduced to such necessities, might not stand a chance of being truer, more wholesome, and more womanly than life under conditions stringently requiring frills and flounces.

As for the Aubrey boys, they found fine fun in the description of the “ship kit” with which the girls would be provided on payment by each of £1, which seemed, indeed, a very moderate sum to buy “a pillow and a bed, a rug, two sheets, one wash-basin, one plate, one pint drinking-mug, one knife and fork, two spoons, three pounds of marine soap, and a canvas bag.”

As a matter of fact, Bell and Annie took with them considerable outfits of a plain, serviceable kind. Old under-linen and stockings, even of extreme “holeness,” as Bell expressed it, were utilised for voyage use, to be worn through once more and then thrown overboard, to spare the labour and discomfort of ship-washing. Each girl was provided with two robes, made in easy dressing-gown fashion, the one of dark flannel for use during the colder parts of the voyage, the other of strong “Oxford shirting” for the tropical regions. For head-gear, each had a thick wadded hood, and a light straw hat of wide, antiquated shape, which Bell picked up for a few pence at a village shop. In the matter of shoes they happened to be particularly fortunate—a friend of Dr. Aubrey’s presenting each with a pair of “alpargátas,” an article worn in Spain and Spanish colonies, and which might be introduced into this country with great advantage, since it gives the maximum of warmth and protection from damp with the minimum of weight and noise. When Bell put them on she said she felt “like a cat.” The upper part of this shoe is roughly made of any material (in this case it was white canvas), tightened across the instep by bright-coloured braid, while the sole consists of fine rope twisted and bound into the proper shape. The article might form a new industry for the blind or for cripples, and has many special advantages for wear in kitchens or in hospital wards.

They found they would not be allowed to take trunks into their berths, and that the clothes for use on the voyage would have to be contained in the “canvas bag.” So they each made themselves a second and smaller bag, which they stocked with underclothing neatly cut out, which they could make up during the leisure of the three months’ voyage; and being duly warned that they would find such leisure very long and tedious, they further provided themselves with materials for lace-work, selecting them as capable of being packed into very small compass. They provided themselves with plenty of foreign writing paper, a big and strong travelling inkstand, some pencils, and a few sheets of stronger paper for possible sketches.

Inquiry proved that the ship commissariat would be ample and wholesome for all ordinary purposes, but that emigrants usually provided against emergencies by a few little dainties of their own. Therefore they procured an ordinary tin biscuit-box, which they stocked with the following creature comfort: two pounds of good tea, a pound of fine sugar, a small box of figs, a pot of Liebig’s extract of meat, and a bottle of strong home-made calves’-foot jelly.

There was a good deal of fun over these little arrangements and the many wild suggestions which were made. The interest in the girls’ adventure had spread beyond the Aubrey household, and they were for the time the heroines of the neighbourhood.

“How happy everything seems!” Annie Steele mused, as she jogged home in the Aubreys’ old chaise, through sweet newbudding English lanes, steeped in silvery moon light. “I have just learned to love my country and to find how kind its people are, as I am going away. But is there not something like that all through life? I have heard old people say that we have only just learned how to live when it is nearly time for us to die. It seems sad, if one looks at it only in one way, but not in another. Perhaps it is God’s way of teaching us that love is the only true possessing, and that this life is but the school for another.”

There was a little pathos in packing the trunks, which would be opened and unpacked so far away, and amid such different scenes. Bell would pack hers entirely herself, the secret of which she confided to Annie.

“If mother or the girls did it, I could not bear to lift out and unfold the things when I get there!” she said, looking straight into Annie’s face. Annie’s own eyes filled in a moment, but Bell’s remained bright and dry.

Those trunks were most sensibly stocked. No ready-made bonnet or hat was taken; only useful materials for the same, nicely prepared, were neatly packed away. Then followed some plain dresses suitable for a hot climate, and a pretty store of neat ribbons and washing frills, folded up “in the rough,” together with packets of buttons, marked stockings, thread gloves, and other little sundries which would spare the young emigrants’ purses for a long time after their arrival. They had a due store of well-chosen books, each of them with some dear autograph in it, mostly flanked by a date or the name of some place, which would serve to keep tender memories alive. One friend contributed a few sheets of the newest music. The invalid Miss Aubrey set herself busily to copy some simple “outline” work, which adorned the bedrooms at home, and whose replica would take little space in packing, and would give a kindly welcoming look to the strange home in the far-off land. Another sister added two or three hand-painted wooden plaques for the same purpose, while a little portfolio was made up for each girl containing as many slight sketches, small engravings, &c., as could be mustered.

At last came the letter from the secretary of the emigration society, bidding both the girls to be ready to go on shipboard at a southern port in the first week in April, and announcing that six more young ladies were also starting out under the same auspices, and that the eight would have the advantage of berthing and messing together, and so escaping all immediate contact with any rougher element.

Bell put in a petition that they should say “good-bye” at the familiar green gate of the old home-garden. “I should like to have my last look of you, all standing together,” she said. “You could not all come to the seaport, even if we could afford the expense, and we should not leave a sweet last impression on each other, if we parted after a day or two of fagging in railway carriages and among our luggage.”

And to her father she said, “Mamma could not come, you know, and it would be terrible for her not to have you beside her in the first shock and silence of our going away.”

And to her sisters she said, “Dear Alice cannot leave her sofa, and it would make her feel her weakness so much to have to stay behind while you came with us.”

And to her mother she said, “It would be very trying for papa to have to part from us at last in the crowd at the depôt, and to return alone by the same road as that on which we had accompanied him.”

Once more, Bell got her way.

But to Annie Steele she said, “All I have urged against their seeing us off is true, but, above all, I did not want them to have too vivid a picture of the hardships we are encountering. It is harder to see what others have to bear than to bear it oneself; and things always look at their worst at an embarkation, and it is not easy to realise how much better they will be when everybody has settled down and the ship is out of dock and on the broad, free ocean.”

So at last they said “good-bye.” Bell even persuaded her father to humour her “last wish” by not driving them to the railwaystation, which was twelve miles from home. The two girls kissed and hugged them all, and then Bell went back into the house to stroke the cat, and came out and kissed and hugged them all again, and then took the reins into her own hands and drove steadily off without looking back till she was so far off that they could not see her face, and she could only discern their forms against the bright spring hedge. There, just where a turn in the road would hide them and the old home from view, she stood up in the chaise and waved her handkerchief—once, twice, thrice; and then as the old horse jogged on again she dropped into her seat, and gave way to one storm of tears. It was not very long, but when it ceased it seemed to Annie Steele to have taken something from Bell Aubrey’s face which never came back again.

But all she said was, “Now we must begin to take notice of everything pleasant, for the sake of the first letter home.”

(To be continued.)

Word Count: 6509

This story is continued in The Other Side of the World, Part 2.

Original Document

Topics

- Adventure fiction

- Girls’ fiction

- Governess Story

- Realist fiction

- Travel Writing

- Women’s literature

- Working-class literature

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Chloe Chytraus

Hallie Hilton

Natalie Fernsten

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

8 March 2025

Last modified

12 February 2026

Notes

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.