The Other Side of the World, Part 2

The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 3, issue 108 (1882)

Pages 257-259

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: Written by Isabella Fyvie Mayo, a feminist writer, “The Other Side of the World” features two young women who are desperate for adventure and freedom to choose their own fates. Written during a time when women didn’t have many career options, this story follows two young women who travel from England to Australia in pursuit of a new life, one where they can be successful. Originally printed in The Girl’s Own Paper, the story was geared towards young girls forging their own paths into adulthood. It features adventure, romance, friendship, and inspiration for young women.

Advisory: This story includes ableist slurs.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the second of three parts:

How the two girls got through their railway journey they never quite remembered. Poor Annie Steele sat wide awake, dreamily looking at the landscape they were flying past, and vaguely thinking over the dull, monotonous details of her life, over whose dreariness there now gleamed a pale ray of that tender sunshine which always illumines the past. She did not speak to Bell, whose dry, glazed eyes and clenched, burning lips told their own tale. Only once, when between station and station they chanced to be alone, she put out her hand to clasp Bell’s, but Bell’s was hastily withdrawn. Only for a moment. The next instant it was outstretched and folded about Annie’s. Bell was of too generous a nature to repel sympathy, even when her heart was so sore that its soft touch wrung it.

But when the girls alighted from the train at Plymouth they felt as if they had awakened from a troubled slumber. There lay the little, wild, scrambling seaport town, full of hearts which knew all about the pains of parting and the aching longing of absence. And there stretched the wide, sunny sea, and there was the soft summer sky bending over it. Bell stood still and drew a long breath.

“When one is out in the open air,” said she, “it seems always as if there was time for everything. I think God’s days are long, so that we can spare to lose sight of each other for a little space, while we do our business and His.”

They took a cab and drove straight to the emigrant depôt. Annie Steele winced a little as Bell gave that address to the cabman, but he received it with so matter-of-fact an air that she felt her shrinking had been quite unnecessary.

“He must have driven others not so very unlike us there before,” pronounced Bell.

The depôt was a huge building, situated in a corner of the harbour, and enclosed by gates. The girls’ hearts sank a little when they found that, having once entered it, they would not be permitted to leave it till they embarked on the tender which would convey them to the emigrant ship.

This they found would not take place till Thursday, and this was Monday. One or two of the lady emigrants had obtained this information beforehand, and had stayed with friends in lodgings in the town; but others of their party who, like themselves, had come from a distance, like them also had taken up their abode in the depôt.

There was nothing to be done but to make the best of things, and the utter novelty of all surroundings made some matters endurable which might have otherwise been hard enough. Despite the medical certificates already obtained, they underwent another medical scrutiny, and were then free of the establishment, and at liberty to introduce themselves to the community of which, for the next three months, they would form a part.

A handsome, dark-eyed young woman, neat in attire and pleasant in manner, looking something like the daughter of a respectable farmer or shopkeeper, came forward to meet them, and saying that she fancied they “must belong to our party,” offered to introduce them to the others, to show them the place, and to “explain things.”

“My name is Miss Gunn,” she said; “I come from Shropshire. I arrived here this morning. Everything seems very queer at first, but I suppose we shall soon get used to it. And our party will keep together. It’s not the tin pannikins and the cleaning-up which signify much—it’s the company. I’m afraid that some of it, not of our party, will not be too select.”

“I suppose not,” said Bell. “You know the secretary never said there would not be hardships, but only that we should encounter nothing that a good woman need shrink from.”

“These are our beds,” announced Miss Gunn, leading the way to a long room with great windows overlooking the beautiful harbour. Annie Steele gave an involuntary grip to Bell’s arm. How queer and dreadful these beds looked!—like nothing so much as tiny “four-posters” all stuck together, with nothing but the posts and a narrow ledge to separate them.

“You are lucky in being two friends,” said Miss Gunn, with a comical grimace. “For we sleep two in a bed, and you two will keep together. My bed-fellow to be has not arrived yet.”

“Why! there are two rows of beds, one beneath the other!” exclaimed Annie Steele.

“Oh, yes,” said Miss Gunn, “and I have not yet made up my mind which is the greater drawback: to have to mount on high when one goes to one’s rest, or to creep into the lower shelf and feel as if a mattress was coming down to extinguish one. But hark, there’s the bell for supper! We must go down at once, though I hope you are not hungry, for we have always to sit waiting nearly half-an-hour before the meal is served. We ‘mess’ ten at a table, but on board, they say, the mess consists of only eight. One of each ten is called the ‘captain,’ and she appoints two ‘butlers’ each day. I am one to-day. Of course, we wash up and sweep the floors ourselves; that is the duty of the ‘butlers’ for the time being, and oh! the knives were dirty to-day—dirty with ancient dirt—but we shall have fresh ones when we go on board.”

“Is the matron here yet?” asked Annie Steele.

“Oh, yes,” replied Miss Gunn.

“And of course she is kind and nice,” observed Bell Aubrey.

“She is like a little cackling hen,” was Miss Gunn’s rejoinder.

“I don’t think our new acquaintance looks on the sunny side of things or people,” whispered Bell to Annie, for she felt by the tightening grasp of Annie’s little hand that her companion’s heart was sinking.

But Annie’s spirits were somewhat revived by the sight of three or four nice girls who came to their mess, and who, belonging to their party, would remain their nearest companions through their long journey. Of course, even names, still less histories, could scarcely be learned at first sight, but shrewd Bell was not long in forming certain opinions about these more interesting fellow-travellers. There was the sensible, worn, rather wearylooking spinster, Miss Wylde, who had probably trodden other people’s staircases, and sat at other people’s tables, till she found the competition for even such humble dependency waxing too strong for her, and who was not so much going out to a new country as being driven forth from the old one. And there was Miss Thorpe, strong and countrified, physically fit for the roughest farm service, and yet with something of breeding and mind that might well make her prefer the harder life and higher chances of a young community to the pampered menialism and rigidly limited range of an old civilisation. And there was Miss Gunn herself, energetic and wiry, with a suspicion of acidity and unrest, which might have mitigated her friends’ regret in parting from her. And there was the pale, picturesque-looking person who called herself “Agnes Perceval” without prefix of Miss or Mrs., whose voice was so low and sad, and whose dark eyes seemed ever fixed upon some vanished scene.

“Now, Annie,” said Bell, softly, as the two walked up and down the little bit of the quay which belonged to the depôt, “there is hardly anything in our new life just now which has not a pathetic and a comic side. We may think of the pathetic one, but I think we’ll speak of the comic one. Is it not funny to find that our food is suddenly become ‘rations’? I mean to send home all particulars about these rations, and then the dear folks will be certainly convinced that we are not starved. We cannot say we have a very limited dietary either, Annie. It contains everything necessary and wholesome, and some decided luxuries. You see it includes beef, pork, preserved meats, suet, butter, biscuits, flour, oatmeal, peas, rice, potatoes, carrots, onions, raisins, tea, coffee, sugar, molasses, mustard, salt, pepper, water, and actually mixed pickles, and lime juice twice a week! Do you suppose Christopher Columbus had such fare? Why, Annie, I begin to think that by-and-by everything will be made so easy and comfortable for everybody everywhere that there will be no chance for heroism. I declare I am cheated out of my dream of adventure. The molasses and the mixed pickles detract from the glory of a pioneer.”

And then there was silence, for Annie could not altogether respond to Bell’s high-hearted appeal. Rather too much of the glory of hardship and adventure still remained for her. Amid the constant shock of strange discomfort she could not help building new hopes that things would be better on the ship.

But after the day of embarkation had come and passed, and they were all fairly on board, when Annie ventured to resume a diary-letter which she had promised Bell’s invalid sister should be kept and forwarded home on the first opportunity, and in which she had already described the depôt, the first line she added was:

“I have told you all about the depôt—now for the ship. It is very much like it—the same four posters, with hardly room to move down the one side that is not joined to other beds. And we eat in the same room, cook in the same room—one room common to a hundred girls, or rather some of them are uncouth, rough Irishwomen. There are few among our ‘mess’ who can take things as bravely as Bell does, or even as I do, for having her with me keeps me up. We are now recovering from what was only to be expected. Some of us are not well yet. Bell was very ill at first, only I was not sea-sick; only directly I went below deck the first night the smell of the room turned me faint. But the ‘rolling’ of the ship has no such effect. At last we have got the place into something like order. I have been down on my hands and knees this morning, doing some honest scouring—such a floor as I have never seen anywhere but in an Irish cabin. I am thankful to say that ‘our mess’ are all once more on their feet. We are a pattern of order. You never see waste in our quarter, and our tin things are always clean. We have a farmer’s daughter among us—Miss Thorpe; she is our cook; and we had a very good tart today. So you see we make ourselves comfortable in spite of circumstances; in fact, after a little sea air, we are rather oblivious of our surroundings during meals. But this happier state of things is only just beginning. The coarse habits of some of the people during the first few days were simply abominable. I think many of us would have turned back if we could, but it only seemed to rouse Bell’s courage.”

A few days later Bell took up Annie’s pen and continued her narrative—

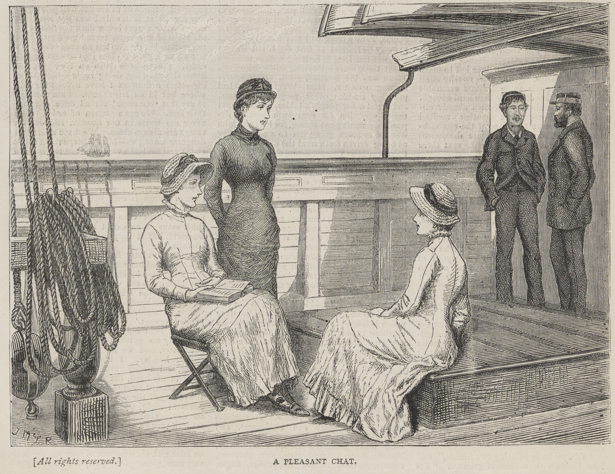

“Things are looking brighter and brighter. For about a week we ‘tipped it up lively,’ as some of the Irish girls sang, but to-day we are becalmed. There are one or two vessels in sight, all like ‘painted ships on painted oceans.’ Oh, it is warm—and yet we have been only one week on the water. Our party are getting more sociable as they get better, and we all feel we are having a regular holiday. I bought a chair at the depôt, and to-day have been sitting with a book in my hand, but did not read much. I am all bruised from the knocks I got through the rolling of the ship, and as we do not sleep much at night, we cannot resist it during the hot day. Though this is the matron’s sixth or seventh voyage, she suffers from sea-sickness, and is keeping her cabin still, though we are all better. There are two sub-matrons, one an Irish girl, the other one of ‘our mess’—both very nice girls. Our party are in very good-favour; when we send our dishes to be baked the ship’s cook improves them, and the officers are all most polite to us; but the Irish have a sort of league among themselves, and are very jealous of everybody. They have threatened to murder one of the sub-matrons when we land. I must tell you something about our doctor, who is always a very important personage on an emigrant ship. Ours is a jovial, amusing fellow, who calls us his “seven and sixpences,” and tells us the funniest little anecdotes, which we only half believe. We all bother him to let us have our boxes up, and he says the word “box” will be found written on his heart, and tells us of a man who came on board a vessel at Glasgow, bound for Sydney, and whose box got lost and could not be found during the voyage. Whenever anything went wrong, or any accident happened, that man always shook his head and hinted that if he could only have got at his box he could have repaired the damage, or done whatever service was required. On arriving at Sydney the famous box turned up among the cargo—a box, says the doctor, 6 feet 4 by 3, and anxious to see what a box so large and so light (for it was light) could contain, he stood by while its owner opened it, and there he saw—a hat, an old pair of shoes, and four red herrings! This story is told to insinuate what he thinks of our declarations that we could be quite happy if we got our boxes. We are about the line now, and have only seen land once, and that was the Cape Verde Islands. I am to be ‘watch’ to-night; the duties are to sit up half the night, to give alarm in case of fire breaking out or water coming in, to shut the ports, if stormy, and keep the lights burning. I have been ‘watch’ once already. Next week I shall be ‘on duty,’ which means that I shall have scrubbing to do, the washing of our mess utensils, &c. I had rather my turn had come in a cooler part, but I shall be glad when it is over. Annie has had her turn already, and got through it very cheerfully. I think she is contented now. I am really enjoying myself. There is a very decent library of fiction on board, but the supply of fancy work to occupy us, of which we were told, is a delusion and a snare. I am glad we brought work of our own, but we might have brought a great deal more. Ours is the only ‘mess’ that has not quarrelled; we set quite an example of sisterly love and community. The captain reads service to us on Sunday morning, and in the afternoon fathers and brothers visit their respective relations. We have a dog, a canary, and two cats on board.”

Later on, Annie Steele resumed the task of reporter.

“On Friday last we saw a meteor. It was like a flame of fire proceeding from a star. The flame disappeared as the meteor shot across the sky. It fell into the sea with a tremendous thundering noise, that I thought would never cease. The heat in the cabin keeps one in a continual bath. As soon as we are down there for the evening we put on our nightdresses, and find them more than sufficient clothing. I must tell you about the cleaning. Before breakfast we take out the boards from the underneath beds, and scrub the boards with dry sand and a heavy stone, then sweep the floor. After breakfast, we wash up, scrub forms, tables, cupboards, and painted walls with soap and water; then take a kind of hoe and scrape the floor, sandstone, and sweep, during which time you require to take a towel half a dozen times to dry yourself! We have had a little rain during the last week; very heavy showers—so refreshing. The phosphorus at night is very pretty, and the fish in a calm look like emeralds. Such quaint groups of people as we see around us it would take volumes to describe. We both look at all your photographs every night, and—,”

Here the letter broke off abruptly, and in a rapid, large hand was added—

“Ship is just starting!”

There seemed to have been no time for any last message, or for even a signature. Some sudden opportunity had evidently been suddenly seized. When the letter reached the Aubreys it looked travel-stained, bore no postage stamp, but was charged only regular postal rates, being marked “ship’s letter.”

(To be continued.)

Word Count: 3109

This story is continued in The Other Side of the World, Part 3.

Original Document

Topics

- Adventure fiction

- Girls’ fiction

- Governess Story

- Realist fiction

- Travel Writing

- Women’s literature

- Working-class literature

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Chloe Chytraus

Hallie Hilton

Natalie Fernsten

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

8 March 2025

Last modified

12 February 2026

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.