The Other Side of the World, Part 3

The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 3, issue 110 (1882)

Pages 289-291

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: Written by Isabella Fyvie Mayo, a feminist writer, “The Other Side of the World” features two young women who are desperate for adventure and freedom to choose their own fates. Written during a time when women didn’t have many career options, this story follows two young women who travel from England to Australia in pursuit of a new life, one where they can be successful. Originally printed in The Girl’s Own Paper, the story was geared towards young girls forging their own paths into adulthood. It features adventure, romance, friendship, and inspiration for young women.

Advisory: This story includes ableist slurs.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the third of three parts:

After the arrival of that most welcome but half-mysterious “ship’s letter,” the Aubreys had to wait a long while before one came with the pretty Queensland postage stamp and the Brisbane postmark upon it; but it came at last, and was opened and read with eager, trembling interest.

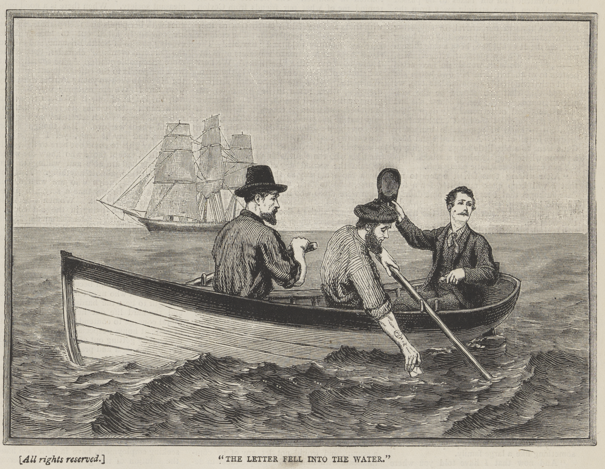

“All my darlings at home,” Bell began. “We are here, safe and well, at last, and as there is scarcely anything to add to our budget about the voyage—for one day is very like another at sea—I will tell you about that budget, which I do hope reached you in safety. I suppose you guess we sent you that letter by a passing ship. We got only three minutes’ notice that there would be a chance of sending home letters. None of the other passengers had time to prepare anything, only, you see, we had obeyed your wishes, and written ours by degrees. We had not even time to sign it, only to find an envelope and direct it; there was not even time to seal it, and the captain kindly threw it to the little boat as they pushed off to the other ship. The letter fell into the water, but they fished it out again, and the captain shouted to them to seal it up for us, and further than that I cannot tell its fate, but we hope it reached you.

“And now I will go on to our landing. As we sailed up Moreton Bay towards Brisbane, we found nothing very striking in the scenery, only it was a treat to our sea-eyes to see any scenery at all! It was quite plain we were going to no out-of-the-world corner, but to a very busy place. Steamers and craft of every kind were passing in and out, and when we got into the Brisbane river the shores were covered with wharves and warehouses and works of every kind, while on the wooded heights behind we caught glimpses of stately villas and pretty cottages. A steamer came down the river to take us off the ship, and on that steamer was the lady (Mrs. F—) who had undertaken to meet ‘our party’ on behalf of the Women’s Emigration Society. We were all allowed to stand with her on the bridge of the boat. When we reached the pier, we watched for our boxes to be passed out, and then drove straight away from the depôt. Of course, had there been any mistake about the time of our arrival, or any other misadventure which had prevented our being met, the depôt would have been a safe though perhaps not a very pleasant refuge. Mrs. F—, in her kindness, would fain have acted hostess to us all, but as in her own house she could only comfortably accommodate one, we decided that that one should be the submatron from our party; for, of course, she had had a great deal of responsibility during the voyage, and deserved the most consideration. Mrs. F— knew of respectable temporary lodgings for all of us. Annie and I and Miss Gunn went to a nice little house belonging to a person whose daughters keep a school.”

Then came a parenthetic paragraph.

“After writing thus far, it occurs to me that I will keep back my letter for a few days, in hopes that I may have some definite news to give you.”

Then followed a later date, and the narrative went on.

“Hurrah! Annie Steele has got a situation as daily governess. She did not get it through the society, but by answering an advertisement. We have left our temporary lodgings and gone to board with some friends of Miss Wylde’s. Annie and I share one room; she will have to pay £40 a year, but I am to get my board free, in return for my household help while I am waiting to hear of something better. The teaching Annie has got already will exactly pay for her board, and no more, but then she only goes to it three days out of the six, and the family are very kind to her, and she hopes to fill up the other three days soon, and so earn twice as much. I think this bright climate is doing Annie good. She seems always bright and happy and in high spirits, and you may guess her energy when I tell you that she has already sent a pretty painted panel to the Brisbane Art Exhibition! I don’t think Annie feels half so lonely here as she did in England. There are so many people in this place who are lonely too, and I fancy a number of lonely people make up something like a large family.

“And now that I have told you where we are and what we are doing, I suppose you will like to hear something of the place, and of our impressions of things in general. Everybody here seems comfortably off; nobody is very rich, and there are no destitute classes. Brisbane itself looks like an incomplete place. Splendid buildings stand side by side with rickety sheds. I have heard it said that ‘Queensland is a fine poor man’s country,’ and I think it is true: the necessaries of life are cheap, but anything in the way of luxury is dear, and so is much that we call ‘comfort,’ and the people seem very careful of their money. In the house where Annie and I are staying there is no servant kept; nobody keeps a servant here who can possibly do without one. Many of the ladies who receive you in pretty caps and laces in the afternoon, in their own drawing-rooms, have spent their mornings in the kitchen and done all their own work. This is a most hard-working country. All the houses have verandahs: in many the rooms are all on one floor. The houses themselves are mostly of wood, the boards of which are beaded and fit into one another, so that there can be no cracks. The rooms generally are very small. Annie and I share one; we have hung up all the crewel work we brought out with us, and what with our little ornaments and photographs, and some home-made brackets, Annie says that, despite its rough boards and rafters, it is the most unphilistine-like apartment she has seen here as yet.

“The climate is simply delicious; but it is winter here now, and everyone talks of being roasted in summer. The flowers and fruit remind me of what our friends from Ceylon used to tell us, and Chinamen come round with fruits and vegetables in baskets as they said the Singhalese people did. The children here are fearfully bold and ‘terrible.’ The street boys are a terror to wayfarers at night. These boys are called ‘Larrikins.’ We hear sad stories of the state of morality in the town. Wines and spirits are mixed with sleeping draughts, when made to be drunk on the premises of licensed houses, and the consumer is robbed, and when he comes to his senses is told that he has drunk the value of his money. It is on sheep-shearers coming into town from the country that this trick is most frequently practised. It is awful to know that some of the girls who came out with us went straight to ruin the second day after the arrival, in much the same way as the shearers, only, of course, more to their utter ruin, and some of them were those who had seemed nice steady girls on board.

“I cannot advise a flood of female emigration to this place under present circumstances. It may certainly be a good opening for sensible young women fit for hard work and willing to do it, or for women who have friends or connections here, or a little capital. Annie and I have been exceptionally fortunate, yet, you see, we are only just paying our way, with not a penny over towards those extra expenses which must come, even to the most economical. Others of our party have got nothing whatever to do yet! Miss Wylde came out believing herself to be engaged as governess in some state official’s family, but when she arrived she found they had secured somebody else: though they would have got her a situation of some sort. Fortunately, she had friends here to go to—the Roys, the family with whom we board and with whom she also is living. I do not think governesses are much wanted here. The grammar school in the town ruins them and the private schools, and chances of teaching up-country are few and far between. A man calling himself a ‘reverend’ wrote up for half-a-dozen governesses, but Mrs. F— says he is a scamp, and would not let any of us communicate with him. The people most in demand are lady-helps, but the work required is rough and the pay small—I have not yet heard more than £20 offered. Under all these circumstances, could one recommend girls to come out here on a loan, either from friends or from the Society, for how could they ever pay it off? Mrs. F— says that the first batch of lady-emigrants whom the Society sent out all got comfortable homes, free of expense, till they got good situations. But they tired their entertainers and went off to their work so reluctantly, that the colonists have left the late-comers to pay their own expenses and shift for themselves. Even in my short experience of life I have been often struck by the reckless way in which people spoil blessings; they don’t take them as ‘talents,’ to be increased in value as they pass them on, but they wear them out, and make them ‘second-hand articles.’”

In due course, other letters followed. Annie Steele presently got a double set of pupils, so that she was comfortably provided for, with a modest margin for saving. And when Bell Aubrey had an offer of a lady-help’s situation in a farmhouse, the Roys found they could not bear to part from her, and entreated her to stay on with them, at the same salary which the farmer was willing to give, namely £25—and Bell, delighted at remaining with Annie, and among faces already grown familiar, gladly accepted the offer.

She wrote, by-and-by—

“Through Mrs. F—’s goodness, and the kindness of Annie’s employers and the cordiality of the Roys, we have got into quite a pleasant society. When there is a good public entertainment in the town, Annie generally goes with her pupils and their parents, and we are constantly asked out to homely little evening parties in South Brisbane, and even to the ‘musical evenings,’ charades, &c., of the more fashionable quarter. Annie actually went with her pupils to the entertainment given by the Mayor to the two young Princes when they were here! We are certainly very happy—only the length of time it takes to receive an answer to a letter makes us realise the immense distance which stretches between us and all whom we love. But though I can say this, and say it truly, yet I could not advise any girls to come out here to fight their own battle, except those who know the world thoroughly and are able and willing to turn their hands to almost anything. It is not fancy-work lady-helps who are wanted, but women who can really take a servant’s place, scrub, wash, and cook. Women like these could easily get a living in the old country without exile, with gentler surroundings, and with, I think, much better pay, especially considering the relative prices of clothing, &c. Of course, you can see from what I have told you that social conditions are somewhat different here, but I feel sure, even among the prejudices of English life, that whatever work ladies did would soon become lady-like! And many women who might not have the physical strength to bear the hardships of the voyage and the hard life out here, might have the moral courage to contend with the remnants of caste at home—especially as those remnants are already getting out of fashion and descending to the vulgar and pretentious classes.

“If English girls of a better class are to be found willing to leave home and friends, and to face all sorts of hardships, and to encounter great risks and difficulties to earn £20 per annum by doing real servants’ work, simply because the public opinion of the strange country does not ostracise them for so doing, then I cannot help saying that English men and women, heads of households at home, and English girls of the better class seeking employment, have in their own hands the solution of the great ‘domestic servant difficulty,’ which, as mamma used to say, makes so much English female life one perpetual struggle and defeat.

“But because I think that many women—and men too, for that matter—might do as well at home as in the colonies if they were prepared to encounter the same hardships and labours, do not imagine that therefore I think women ought not to emigrate. Where the men of a nation go the women should go also. When I see some of the evils and miseries of society out here, and remember the evils and miseries of society in England, I feel that the one-sided way in which emigration has been too often carried on has much to answer for. Society in the colonies is apt to be bare and coarse for lack of the gentler elements of life, and the society at home to grow vapid and indolent through the elimination of its stronger ones. When sons and brothers and friends and neighbours go abroad, I think it would be well if their womenkind and their dependents went with them, instead of getting assistance or support sent to them from abroad. I know that this would involve a great deal of self-sacrifice and courage on the part of such womenkind and dependents, but, then, everything that is worth doing involves self-sacrifice and courage. The Bible says that woman was made to be the help-meet for man, which means, I should think, that she shares and dares with him while he wants help, not that she comes in like a base camp-follower after the victory to divide the spoil! I am glad I came out here. It is the right thing for some women to do, only they should do it knowing exactly what will be expected from them and what they must expect.”

Mrs. Aubrey sat thoughtful with a half smile on her face after she read that letter. At last she said:

“I expect Bell will have some important news for us soon.”

Her motherly instinct was right. The name of a Mr. Edward Wylde, a brother of Miss Wylde’s, had appeared more than once in the girl’s home letters. And at last there came one about nothing else but him, because Bell had promised to marry him as soon as he could build a little cottage on the pretty “lot” he had bought by the river.

Annie Steele wrote about him too, “Because,” she said, “I know you will like an impartial judgment concerning him, which dear Bell’s cannot be. Through our association with his sister and the Roys, we have seen him almost daily since we first arrived. I feel it like an insult to him to say how steady and good he is. I have scarcely ever seen him without a smile on his face and a pleasant word on his lips. He is one of those people who are always ready to help everybody and who hinders nobody. Yet he has a firm will of his own, and a strong sense of right and wrong, and recognises no in-betweens. He has been taking such pride and pleasure in getting ready his married home. It is the sweetest little house, with one pleasant living room, a tiny kitchen, one large bedroom and two small verandah bedrooms, and a lovely garden stretching down to the river’s edge. They have planted two young palms beside the door; and they are to be called ‘the Doctor’ and ‘Mamma.’ All the domestic plans are settling down most happily. Miss Wylde, his sister, who has had two or three uncomfortable situations, is to take Bell’s place at the Roys. Bell will do all her own domestic work, at least at present, and as Edward Wylde often has to be away from home for a day or two on business, I am to take up my abode with the young couple, continuing my daily teaching and paying for my board as I have done at the Roys, but giving Bell the inestimable boon of my cheerful society, during the early mornings and the evenings of her husband’s enforced absences. We mean the wedding to be very quiet and pretty. Heigho! I always told Bell that people would say we came out here to get husbands. And she said we had to do right and not care what people said! And if any girl says that she shrinks from starting for the colonies for fear she would not be able to contrive to keep single, tell her I have been here two years already and have not had a solitary offer!

“Bell says it is so nice to reflect that if, as years pass on, you think some of her younger brothers should try colonial life, there will be a home for them to come to, and experienced friends to meet and advise them. Whether Bell has children of her own or not, I think she will be one of those whom the Hebrew historians called ‘a mother in Israel.’ And these are the sort of women who are wanted in new countries.”

[THE END.]

Word Count: 3185

Original Document

Topics

- Adventure fiction

- Girls’ fiction

- Governess Story

- Realist fiction

- Travel Writing

- Women’s literature

- Working-class literature

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Chloe Chytraus

Hallie Hilton

Natalie Fernsten

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

8 March 2025

Last modified

11 February 2026

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.