The Prince’s Crime: A True Romance of India

The Strand Magazine, vol. 3, issue 8 (1892)

Pages 175-181

Introductory Note: “The Prince’s Crime: A True Romance of India” follows the tragic story of Princess Rajkooverbai, given in marriage by her family to the brutal Prince Chundra Singh. The romantic Oriental tale was written by J. E. Muddock in 1892, near the end of the Victorian Era. The narrative presents a shifting view of “fallen” women in the patriarchal society of the time, while also demonstrating the British romantic view of the exotic, particularly concerning India.

Advisory: This story depicts slavery and domestic violence.

On the banks of the Orsing River, which flows through Oodeypor, and finds its way into the Gulf of Cambay in the Arabian Sea, stands the old and magnificent palace of the Rajas of Chota.1Oodeypor: A small area in the province of Rajasthan, India. The present Raja, Jit Singh, the Chowan, or ruler, is the seventeenth in direct line from Peilab Singh, who long ago was the terror of his country, for the only law he recognised was the law of the sword. Jit Singh possesses many of the qualities of his famous ancestor, and, though an independent Prince, and known as “The Lion of Victories,” he is tributary to his more powerful neighbor of Baroda. The palace of Jit Singh is noted for its magnificence. Some of the apartments are decorated with barbaric splendour. In the “Mirror Room” the ceiling is inlaid with real gold and jewels, while the walls are lined with mirrors of burnished silver. In the feudal times the Palace was often besieged; and often, too, there went forth from its grim precincts the Chowan with a powerful following to make war on some neighbouring State. There is a current tradition in connection with the House of Chota that a former Raja had a daughter of entrancing beauty whose hand was sought by two powerful princes. As the Raja did not wish to offend either of them, he bade them fight for the Princess. One was slain, and, when the survivor claimed the hand of the beauteous maiden, her father, being afraid of giving deadly offence to the relatives of the slain prince, put his daughter to death. This Spartan-like spirit has ever been conspicuous in the descendants of the redoubtable Peilab Singh, and it displayed itself a few years ago in Chundra Singh, the second son of the present ruler, whose subjects number between seventy and eighty thousand.

Some years ago Chundra Singh married a lady who was considerably his senior, and she resided in his zenana in part of the old palace.2Zenana: The part of a house (particularly one belonging to a Hindu or Muslim family) that is meant specifically for the seclusion of women. Three years later Chundra fell in love with the Princess Rajkooverbai, who was the only sister of a powerful noble in a neighbouring State. The Princess was but fifteen years old, but the fame of her beauty had spread throughout almost the whole of India. Her family had ever been noted for the courage of its men, and the beauty of its women; and in Rajkooverbai beauty and courage were blended, so that high-born Hindoos from far and wide sought—her hand. But Chundra’s suit found favour with her brother, and he consented to the Princess allying herself with the powerful house of the Chota Rajas; for, though Chundra was the second son, there were probabilities that one day he would rule. But, whether or no, an alliance with such a family was not to be despised. So the wedding was celebrated with all the regal pomp and magnificence which mark Indian marriages in high life.

The name of Chundra’s first wife was Naudba, and when her girlish rival, whose dazzling beauty so eclipsed her own, was brought to the zenana, she displayed a fierce hatred for her from the very first meeting. For some time poor little Rajkooverbai tried to propitiate the haughty Naudba, but without success, and the girl’s life was made a burden to her. So unhappy did she become that her husband at last gave her private apartments in his palace, and here, with a few attendants, she led a lonely life, though it was preferable to the misery and wretchedness she had endured at the hands of Naudba.

It chanced, unhappily for the Princess, that amongst her husband’s retainers was a handsome youth, a young Beluchi, whose name was Saadut. He was the son of a soldier, who was also in the Prince’s service, and he had the reputation of being a musician and a poet. He had received an education superior to most youths in his station of life; and, being of a studious and observant nature, he had already made himself conspicuous for his knowledge. The result was he became a general favourite in the Palace, and his master allowed him many privileges. Moreover, being of an amorous disposition, he penned love-sonnets for his companions; and, as he was able to play the cithar well, he set his sonnets to music, and sang them during the languid Indian nights, when, the labours of the day being over, the retainers were free to enjoy themselves after their bent.3Cithar: A stringed instrument of India with a seasoned gourd body, a hollow wooden neck, and raised frets.

Saadut’s accomplishments and handsome appearance attracted the attention of the proud and cruel Naudba, to whom it suddenly occurred that she might make him an instrument for ridding herself of her hated rival, the Princess Rajkooverbai, who was the favourite of her husband. “If she were dead,” argued Naudba, “I should have the undivided attention and affection of Chundra.” Having brought herself to this frame of mind, she set herself to work to give effect to her desires; and, by the aid of a trusty servant, she sent an artfully couched message to the handsome boy, in which it was hinted that the beautiful Princess Rajkooverbai had, while sitting behind her purda of pierced marble, and which commanded a view of the courtyard, frequently gazed with longing eyes upon him, and that he had only to play his cards well to win her favours and her love.4Purda: Certain Muslim and Hindu societies used the practice of “purda” or “purdah” to screen women from men or strangers. Usually this was accomplished by means of a curtain, which is also referred to as a “purda” or “purdah.”

The designing and treacherous Naudba did not overestimate the material she had to work upon. The mind of Saadut was inflamed, and his vanity flattered. To have attracted the attention of so renowned a beauty as Princess Rajkooverbai was indeed a thing to be proud of, from his point of view. Now, it was true that the poor little Princess did sit daily behind her screen, where she could see without being seen; and in her lonely captivity—for the wife of an Indian noble is little better than a captive—she had no doubt heard the laughter and the bustle that went on all day in the courtyard, and longed and sighed for the freedom enjoyed by the humble followers of her lord, but which—high born as she was—was denied to her. She must even have seen Saadut often enough, and heard him singing his love ditties at night as he accompanied himself on the cithar, while his admiring companions lounged about, and smoked their nilgherries, and bubble-bubbles. Probably, too, her woman’s heart may have beat a trifle faster as she gazed on his handsome face, and heard his melodious voice, though it is doubtful whether she would have taken the initiative in making known to him that he had raised in her feelings of admiration. But Saadut, believing the message that had been sent to him, began to dream dreams, and often when the Princess was being carried to her bath in the morning he placed himself in such a position that he got glimpses of her as she reclined in her magnificent palanquin; and, fancying that his amorous glances found favour, he grew bolder, and, composing love songs artfully framed to make known his passion, he sang them beneath her apartments when he knew that she was seated behind the carved marble purda with none but her women attendants about her.

“Love hath a special voice, and speaks only in one language,” says an Indian proverb. And soon, Princess Rajkooverbai, pining in her lonely grandeur, and sighing for the liberty denied to her, but which was enjoyed by those of lowlier birth, awakened to a consciousness of the fact that the handsomest youth amongst all her husband’s retainers was filled with love for her. No wonder that her head was turned, when all the circumstances of the case are considered, and, notwithstanding the terrible danger she must have known she ran, she began to give Saadut signs that she was not indifferent to his attentions.

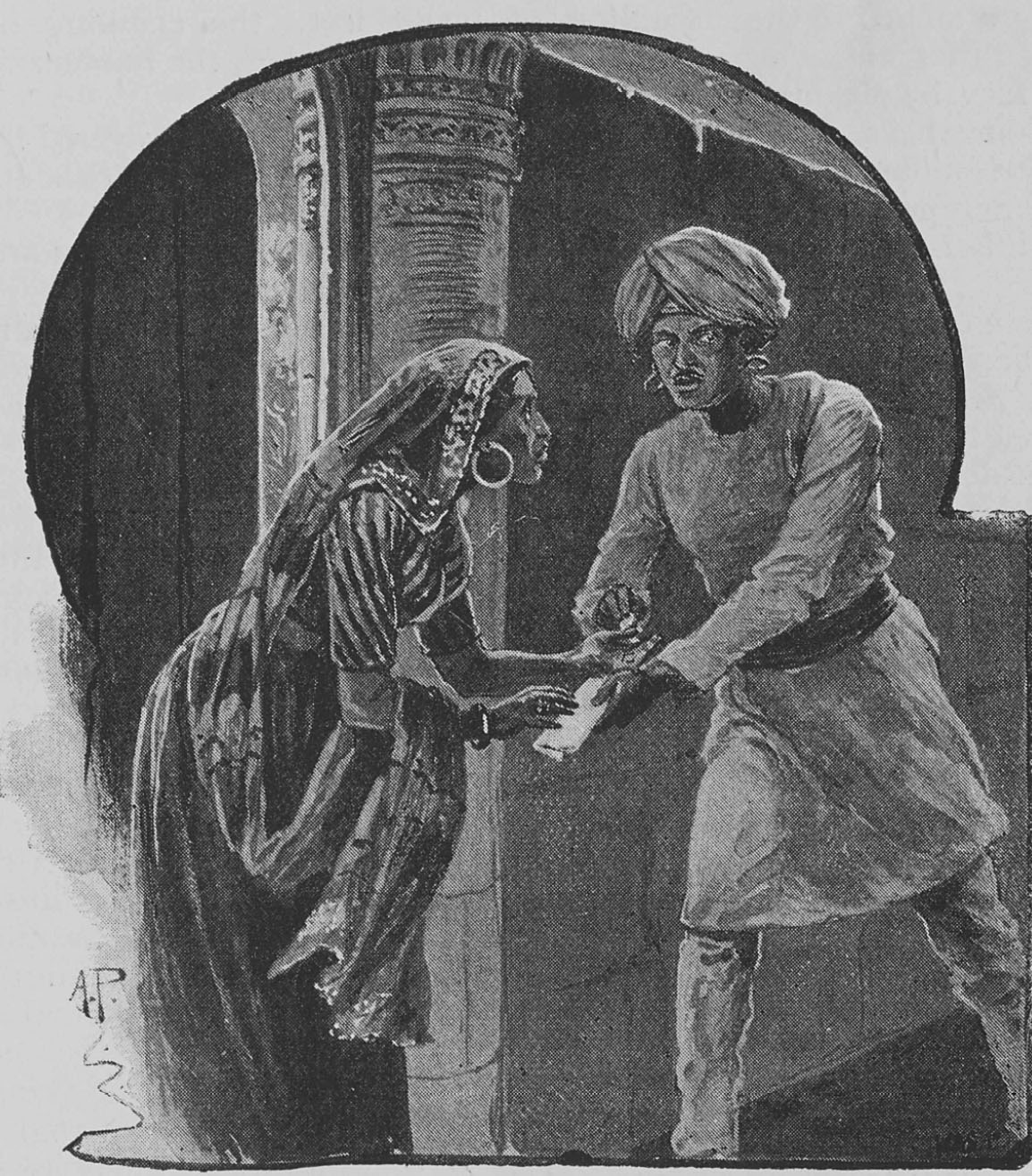

Encouraged by this, Saadut grew still bolder, and he bribed a woman of the Palace to convey a love song he had specially written to the Princess.

For some days he waited in dread suspense, wondering what would be the fate of his missive. He knew perfectly well that his life would not be worth an hour’s purchase if the great Chowan came to know that he, a servant, had dared to breathe love to the Princess. But at last his mind was relieved by the receipt of an answer from Rajkooverbai, which she had entrusted to a faithful slave.

For months a correspondence was thus kept up between the girl Princess and the boy retainer, until at last Saadut was moved to plead with the beautiful girl to grant him an interview. Unable to resist his prayer, she sent back word that on a certain night he might climb to her chamber window by means of a rope ladder she would throw out. The window of the chamber in which was the Princess’s couch was little more than twelve feet from the ground, and faced a private garden that was at right angles with the courtyard, but which it was looked upon as all but sacrilege for the servants to enter, as it was sacred to the ladies of the zenana. But what will love not dare! The night chosen for the meeting was one when the lovers knew there would be no moon, and the hour when the Chowan and his sons had sat down to their evening meal. As in most Indian chambers of the kind, the couch was so arranged that it could be turned into a swinging cot, if desired, by means of hooks in the ceiling, to which cords were attached. The Princess, who had dismissed all her attendants but the faithful slave, caused the slave to knot one of the cords, and lower it from the window. Such a means of ascent presented no difficulties to an Indian youth, and Saadut—who having surreptitiously obtained entrance into the garden, was lying in wait—seized the cord, and in a few moments he and the Princess were clasped in each other’s arms. The meeting was necessarily of short duration, but when the lovers parted they vowed to meet again.

Let it not be supposed that during the time Saadut had been making known his passion for Rajkooverbai the jealous and wicked Naudba had remained indifferent. She had lighted the fire, and eagerly she watched its progress, for she had spies all over the Palace; and that first meeting at the window was made known to her. But, with devilish artfulness, she determined that the time was not yet ripe for bringing the matter under the notice of Chundra. He was greatly attached to the Princess, and Naudba feared that, unless he was aroused to a pitch of fury by jealousy, he would overlook Rajkooverbai’s indiscretion, and forgive her. So Naudba waited, like a tigress waiting for her prey. She knew that if she was patient her prey would be secured.

All unaware of their danger, the lovers were emboldened by that first meeting, and three or four letters a day passed between them. At last they resolved to meet again, and an assignation was made. This time the Princess arranged to leave her chamber by means of the knotted cord, and go to a bower in the garden.

The night came, and, as it seemed to the lovers, the very elements favoured them; for not only was it intensely dark, but rain was falling. At the appointed hour, and while her lord feasted, Rajkooverbai silently threw open her casement, and, with the aid of her devoted slave, slid down the cord and fled to the bower where Saadut was waiting for her.

All was silent, save for the whirring and chirping of the thousand and one insects that make an Indian night melodious. The soft rain pattered on the great palm leaves, and drove the fireflies to seek shelter; but the odours of many flowers made the air languid and dreamy. External influences, however, affected not the lovers. Clasped in each other’s arms they forgot everything save the passion of love, and on each other’s lips they sealed their devotion. But suddenly sounds arose to which they could not be deaf. They became aware of some extraordinary commotion in the Palace. There was the scuffling of many feet, the clanking of arms, the flashing of torches, the hubbub of men’s voices.

“Allah save us! We are discovered!” whispered the Princess. “Fly—fly, Saadut, as you love me!”

“No,” he answered, firmly; “as you are in danger I will share it with you.”

“Saadut, Saadut!” she moaned, “pain me not. I may be able to appease my lord’s anger; but, should he discover us together, he will slay us both.”

“I cannot go and leave you to his wrath,” replied Saadut, who was a brave youth. “Fly with me; we may easily gain the river, where we can obtain a boat, and before the day breaks we will be far away.”

Rajkooverbai was more practical than he was, and assured him that flight was impossible. Her husband’s mounted retainers would scour the country, and leave no road open. Their only chance of escape was by relying on her woman’s wit, and trusting to her influence over her husband. In spite of this argument, Saadut seemed reluctant to go. But the commotion was increasing. It was evident the whole Palace was aroused, and Chundra’s deep voice could be heard as in angry tones he called his followers to surround the garden; and already the glare of the torches shone upon the dripping foliage.

“Go—go, in the name of Brama, I beseech you,” pleaded the poor Princess, in terrible distress.5Brama: The first god of the Hindu triumvirate. And, unable to resist her pleadings, Saadut hastily embraced her, and had scarcely time to disappear amongst the thick bushes and clustering palm trees, and climb over a high wall, before the garden was filled with armed men, with Chundra leading them. Swathing her face in her veil, Rajkooverbai slowly approached her enraged husband, and, restraining her excitement as best she could, she asked, as she knelt to him, “What does all this mean, my lord?”

“Foul and degraded being,” he answered, “it means that you have dishonored my name and house, and I am going to kill you.”

The Princess rose to her feet proudly, and, believing that her lover was not known, and had effected his retreat, she cared nothing for herself.

“If you think I have dishonoured you,” she said courageously, “kill me, but not here. Make not our trouble public. Let me go in, and I will kill myself quietly, and you can say I have died of some sudden illness.”

To this her husband’s only reply was a terrific blow with a staff he carried. And he beat her until she fell quivering to the ground. But in a few moments she sprang up by a desperate effort, and exclaimed with fiery energy:

“My lord, I am not a bullock, that you should beat me thus. I am of royal blood, and demand such treatment as is due to a Princess.”

Again her husband’s only reply was a savage blow that once more felled her to the ground. Then, ordering some of the servants to convey her to her chamber, he told others to follow him. And he made his way to the courtyard, and to the quarters occupied by the guard of the Palace. His object was to see Saadut’s father, and compel him to produce his son; for Naudba’s spies, who had conveyed the information that the Princess had escaped from her room, also stated that Saadut was the lover. But what was Chundra’s surprise, when he reached the guardhouse, to find the youth calmly seated, surrounded by companions, to whom he was singing. For the moment the Prince’s suspicions were allayed, so far as the lad was concerned. He thought that he must have been misinformed; and, without speaking, he strode back to the Palace, still maddened with jealous rage.

In the meantime Princess Rajkooverbai had been taken to her apartments. She was battered and bruised by the severe beating her husband had given her. But she showed no signs of fear; she uttered no moan. And now the savage Chundra burst into the room.

“What is the name of thy lover, false one?” he cried menacingly.

She drew herself up with all the pride of her race, and made answer:

“Think you, my lord, that even if I had a lover I should betray him?”

“Do not seek to deceive me,” roared Chundra, “or I’ll hack you to pieces.”

“Kill me,” she answered calmly, “as it so pleases you. But forget not that I am your wife, and of birth as noble as your own. And if you kill me there are those who will avenge my death.”

This answer seemed to enrage him more, and he ordered the cowering servants to seize her, and make the cord by which she had lowered herself from the window fast to her ankles. This being done, she was drawn up by means of the hook in the ceiling, and, while she hung in this terrible position, head downwards, her brutal husband belaboured her with a staff until it broke. Then he called for a tulwar, and beat her with the flat part until her dainty flesh was hacked and bleeding.6Tulwar: a type of curved sword used primarily in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. At last his passion appeared to exhaust itself, and he gave orders that the suffering girl should be released and laid upon her couch.

While this terrible scene was being enacted in the palace, Saadut, yielding to the urgent entreaties of his father, was flying through the darkness of the night to his native village, where he hoped to be safe for a time. But when Chundra left his wife’s room, he went straight to Naudba and demanded angrily if she was sure that Saadut was the lover. In reply Naudba produced her spies, who stated positively that it was Saadut. Then the Prince told some of his retainers to arrest the youth, and bring him to the vaults beneath the Palace. And a huge Arab slave was ordered to have ready a large crucible of boiling lead. In a very short time, however, word was brought to the Prince that Saadut was nowhere to be found. This seemed confimatory of the lad’s guilt, and Chundra offered a reward of a thousand rupees for his capture.

The next day Chundra visited his wife again. She was in a terrible state, and unable to move, nevertheless, on her firmly refusing to name her lover, he once more beat her; though, in spite of the torture and agony she suffered, not a sound of murmuring escaped her lips. When the night came and there was no word of Saadut having been captured, the brutal Prince repaired once more to Rajkooverbai’s chamber. But she was now in a condition that his brutality could no longer affect her, for she was quite unconscious, and such a pitiable spectacle from the wounds he had inflicted that few men could have looked upon her without being moved. But Chundra was a Rajput Prince, and pity was unknown to him, when he considered that the honour of his house was at stake, and that wrongs were to be avenged, so, all unconscious as she was, he beat her again and again.

A few hours later, when the Indian dawn was breaking with a dazzling splendour of crimson and gold, poor Princess Rajkooverbai heaved a deep sigh, and, with a smile upon her beautiful face, passed away to one of the seven heavens, where man’s brutal passions avail not.

When the Prince was informed of her death, he ordered a report to be spread that she had died of snake-bite, for he knew that, though he was the son of Raja Jit Singh—the Lion of Victories—he might have to answer to the all-powerful Kaisar-i-Hind, the Empress of India, who would tolerate no murder in her dominions if she could help it. Time had been when an Indian Prince could have beaten a dozen of his wives to death, and all that it would have led to would have been a feud, perhaps, between himself and some of his dead wives’ relatives. But those days had gone by; the fierce arbitrament of the sword had given place to the scales of Justice, and Chundra was fully aware that his brutal deed would be called murder in the more enlightened age in which he lived.

By a strange coincidence, on the very day of Princess Rajkooverbai’s death, Saadut was captured by some of Chundra’s retainers who had been stimulated in their endeavours by the promised reward of a thousand rupees. They found him in his native village, about thirty miles away; he was kidnapped by a ruse and borne swiftly on horseback to the Palace, where he arrived as the sun was going down.

Women had already laid out the Princess’s mangled body, which was now borne secretly through the Palace grounds to the burning ghat, on the banks of the Orsing, where a funeral pyre had already been prepared. No time was lost. The body of the beautiful girl was laid on the pyre, which was immediately fired, and, as the flames mounted high towards the darkening sky, two powerful Hindoos—looking stern and grim as avenging gods—came from the Palace grounds, leading between them the ill-starred Saadut, whose hands were bound close to his body. They led him to the burning pyre, and one of them said sternly:

“Behold thy handiwork. She who through you dishonoured her lord is being consumed there, and the dark waters of the river that roll on to Cambay’s Gulf will bear your accursed soul to the place of the damned, whither she has gone.”

Before the youth could make any reply, a silken cord was dexterously twisted round his neck, and he was quickly strangled to death. Then the cords that bound him were cut, and his body was tossed into the rapidly flowing stream and quickly disappeared from sight.

Two hours later the funeral pyre had done its work, and a heap of white ashes alone remained. Then Prince Chundra, of the House of Singh, came from his Palace, and the ashes were collected into a brass bowl and given to him. And standing on the banks of the river he muttered a malediction, and tossed the ashes of his murdered wife to the winds. And all fear of any medical evidence of the cause of her death being obtained was now past. Thus was consummated one of the cruelest and most romantic crimes that even the annals of India can furnish.

Word Count: 4025

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

J. E. Muddock. “The Prince’s Crime: A True Romance of India.” The Strand Magazine, vol. 3, no. 8, 1892, pp. 175-81. Edited by Rachael Buchanan. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 4 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-princes-crime-a-true-romance-of-india/.

Editors

Rachael Buchanan

Taylor Topham

Christina Peregoy

Hannah Murdock

Posted

3 January 2018

Last modified

4 July 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | Oodeypor: A small area in the province of Rajasthan, India. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Zenana: The part of a house (particularly one belonging to a Hindu or Muslim family) that is meant specifically for the seclusion of women. |

| ↑3 | Cithar: A stringed instrument of India with a seasoned gourd body, a hollow wooden neck, and raised frets. |

| ↑4 | Purda: Certain Muslim and Hindu societies used the practice of “purda” or “purdah” to screen women from men or strangers. Usually this was accomplished by means of a curtain, which is also referred to as a “purda” or “purdah.” |

| ↑5 | Brama: The first god of the Hindu triumvirate. |

| ↑6 | Tulwar: a type of curved sword used primarily in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. |