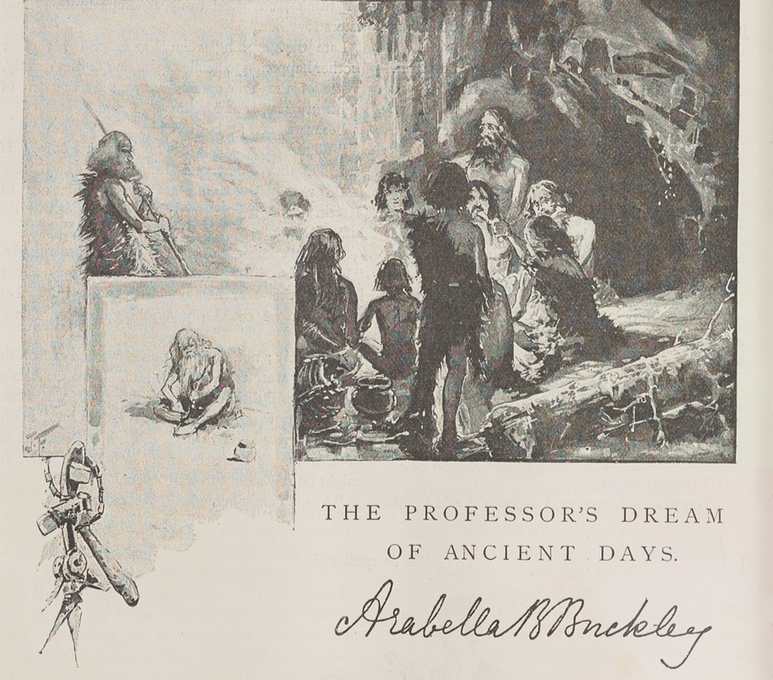

The Professor’s Dream of Ancient Days

Atalanta, vol. 1, issue 3 (1887)

Pages 130-135

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Professor’s Dream of Ancient Days” relates the experience of a fictional professor who, having fallen asleep, personally experiences specific scenes throughout the history of man in “palæolithic,” “neolithic,” and bronze-age eras of Great Britain. This educational story was published in the girl’s journal Atalanta, known for its advocacy of girl’s education in science and history. Written during a period of high fascination with natural history, this story also helps to convey the Victorian understanding of the history of mankind.

THE Professor sat in his arm-chair in the one little room in the house which was his, and his only. And a strange room it was. The walls were hung with skulls and bones of men and animals, with swords, daggers and shields, coats of mail, and bronze spear-heads. The drawers, many of which stood open, contained flint stones, chipped and worn, arrowheads of stone, jade hatchets beautifully polished, bronze buckles and iron armlets; while scattered among these were pieces of broken pottery, some rough and only half-baked, other beautifully finished, as the Roman knew how to finish them. Rough needles made of bone lay beside bronze knives with richly-ornamented handles, and, most precious of all, on the table by the Professor’s side lay a reindeer antler, on which was roughly carved the figure of the reindeer itself.

The Professor had been enjoying a six weeks’ holiday, and he had employed it in visiting some of the bone caves of Europe to learn about the men who lived in them long, long ago. He had been to the south of France to see the famous caves of the Dordogne, to Belgium to the caves of the Engis and Engihoul, to the Hartz Mountains and to Hungary.1The caves of the Dordogne in southwestern France house prehistoric art; the Engis and Engihoul caves in Belgium were thought to have housed proto-human skeletons; “Hartz Mountains” most probably refers to the Harz mountain range in Germany, which is known as a former hunting ground for prehistoric man. Then hastening home he had visited the chief English caves in Yorkshire, Wales, and Devonshire.

Now that he had returned to his college, his mind was so full of facts, that he felt perplexed how to lay before his students the wonderful story of the life of man before history began. And as the day was hot, and the very breeze which played around him made him feel languid and sleepy, he fell into a reverie—a waking dream.

********

First the room faded from his sight, then the trim villages disappeared; the homesteads, the cornfields, the grazing cattle, all were gone, and he saw the whole of England covered with thick forests and rough uncultivated land. From the mountains in the north, glaciers were to be seen creeping down the valleys, between dense masses of fir and oak, pine and birch, while the wild horse, the bison, and the Irish elk were feeding on the plains. AS he looked southward and eastward he saw that the sea no longer washed the shores, for the English and Irish Channels were not yet scooped out. The British Isles were still part of the continent of Europe, so that animals could migrate overland from the far south up to what is now England, Scotland, and Ireland. Many of these animals, too, were very different from any now living in the country, for in the large rivers of England he saw the hippopotamus playing with her calf, while elephants and rhinoceroses were drinking at the water’s edge. Yet these strange creatures did not have all the country to themselves, wolves, bears, and foxes prowled in the woods, large beavers built their dams across the streams, and here and there over the country human beings were living in caves and holes of the earth.

It was these men chiefly who attracted the Professor’s attention, and being curious to know how they lived he turned towards a cave, at the mouth of which was a group of naked children who were knocking pieces of flint together, trying to strike off splinters and make rough flint tools such as they saw their fathers use. Not far off from them a woman with a wild beast’s skin round her waist was gathering firewood, another was grubbing up roots, and another venturing a little way into the forest was searching for honey in the hollows of the tree trunks.

All at once in the dusk of the evening a low growl and a frightened cry were heard, and the women rushed towards the cave as they saw near the edge of the forest a huge tiger with sabre-shaped teeth struggling with a powerful stag. In vain the deer tried to stamp on his savage foe or to wound him with his antlers. The strong teeth of the tiger had penetrated his throat, and they fell struggling together as the stag uttered his death-cry. Just at that moment loud shouts were heard in the forest, and the frightened women knew that help was near.

One after another, several men, clothed in skins hung over one shoulder and secured round the waist, rushed out of the thicket, their hair streaming in the wind, and ran towards the tiger. They held in their hands strange weapons made of rough pointed flints fastened into handles by thongs of skin, and as the tiger turned upon them with a cry of rage they met him with a rapid shower of blows. The fight raged fiercely, for the beast was strong and the weapons of the men were rude, but the tiger lay dead at last by the side of his victim. His skin and teeth were the reward of the hunters, and the stag he had killed became their prey.

How skillfully they hacked it to pieces with their stone axes and then loading it upon their shoulders set off up the hill towards the cave, where they were welcomed with shouts of joy by the women and children!

Then began the feast. First fires were kindled slowly and with difficulty by rubbing a sharp-pointed stick in a groove of softer wood till the wood-dust burst into flame; then a huge pile was lighted at the mouth of the cave to cook the food and keep off wild beasts. How the food was cooked the Professor could not see, but he guessed that the flesh was cut off the bones and thrust in the glowing embers, and he watched the men afterwards splitting open the uncooked bones to suck out the raw marrow which savages love.

After the feast was over he noticed how they left these split bones scattered upon the floor of the cave mingling with the sabre-shaped teeth of the tiger, and this reminded him of the bones of the stag and the tiger’s tooth which he had found in Kent’s Cavern in Devonshire only a few days before.

By this time the men had lain down to sleep, and in the darkness strange cries were heard from the forest. The roar of the lion, mingled with the howling of the wolves, and the shrill laugh of the hyænas told that they had come down to feed on the remains of the tiger. But none of these animals ventured near the glowing fire at the mouth of the cavern, behind which the men slept in security till the sun was high in the heavens. Then all was astir again, for weapons had been broken in the fight, and some of the men sitting on the ground outside the cave placed one flint between their knees and striking another sharply against it drove off splinters, leaving a pointed end and cutting edge. They spoiled many before they made one to their liking, and the entrance to the cave was strewn with splintered fragments and spoilt flints, but at last several useful stones were ready. Meanwhile, another man taking his rude stone axe, set to work to hew branches from the trees to form handles, while another choosing a piece remaining of the body of the stage, tore a sinew from the thigh, and threading it through the large eye of the bone needle, stitched the tiger’s skin roughly together into a garment.

“This, then,” said the Professor to himself, “is how ancient man lived in the summer-time, but how would he fare when winter came?” As he mused the scene gradually changed. The glaciers crept far lower down the valleys, and the hills, and even the lower ground, lay think in snow. The hippopotamus had wandered away southward to warmer climes, as animals now migrate over the continent of America in winter, and with him had gone the lion, the southern elephant, and other summer visitors. In their place large herds of reindeer and shaggy oxen had come down from the north and were spread over the plains, scraping away the snow with their feet to feed on the grass beneath. The mammoth, too, or hairy elephant, of the same extinct species as those which have been found frozen in solid ice under a sandbank in Siberia, had come down to feed, accompanied by the woolly rhinoceros; and scattered over the hills were the curious horned musk-sheep, which have long ago disappeared off the face of the earth.

Still, bitterly cold as it was, the hunter clad in his wild beast skin came out from time to time to chase the mammoth, the reindeer, and the oxen for food, and cut wood in the forest to feed the cavern fires. This time the Professor’s thoughts wandered down to the south west of France, where, on the banks of a river in that part now called the Dordogne, a number of caves not far from each other formed the home of savage man. Here he saw many new things, for the men used arrows of deer-horn and of wood pointed with flint, and with these they shot the birds, which were hovering near in hopes of finding food during the bitter weather. By the side of the river a man was throwing a small dart of deer-horn fastened to a cord of sinews, with which from time to time he speared a large fish and drew it to the bank.

But the most curious sight of all, among such a rude people, was a man sitting by the glowing fire at the mouth of one of the caves scratching a piece of reindeer horn with a pointed flint, while the children gathered round him to watch his work. What was he doing? See! gradually the rude scratches began to take shape, and two reindeer fighting together could be recognized upon the horn handle. This he laid carefully aside, and taking a piece of ivory, part of the tusk of a mammoth, he worked away slowly and carefully till the children grew tired of watching and went off to play behind the fire. Then the Professor, glancing over his shoulder, saw a true figure of the mammoth scratched upon the ivory, his hairy skin, long mane and up-curved tusks distinguishing him from all elephants living now. “Ah,” exclaimed the Professor aloud “that is the drawing on ivory found in the cave of La Madeleine in Dordogne, proving that man existed ages ago, and even knew how to draw figures, at a time when the mammoth, or hairy elephant, long since extinct, was still living on the earth!”

With these words he started from his reverie, and knew that he had been dreaming of a Palæolithic man who, with his tools of rough flints, had lived in Europe so long ago that his date cannot be fixed by years, or centuries, or even thousands of years. Only this is known, that, since he lived, the mammoth, the sabre-toothed tiger, the woolly rhinoceros, the cave-hyæna, the musk-sheep, and many other animals have died out from off the face of the earth: the hippopotamus and the lion have left Europe and retired to Africa, and the sea has flowed in where land once was, cutting off Great Britain and Ireland from the continent.

How long all these changes were in taking place no one knows. When the Professor drifted back again into his dream the land had long been desolate, and the hyænas, which had always taken possession of the caves whenever the men deserted them for awhile, had now been undisturbed for a long time, and had left on the floor of the cave, gnawed skulls and bones, and jaws of animals, more or less scored with the marks of their teeth, and these had become buried in a think layer of earth. The Professors knew that these teeth-marks had been made by hyænas both because living hyænas leave exactly such marks on bones in the present day, and because the hyæna bones alone were not gnawed, showing no animals preyed upon their flesh. He knew too that the hyænas had been there long after man had ceased to use the caves, because no flint tools were found among the bones. But now the age of hyænas, too, was past and gone, and the caves had been left so long undisturbed that in many of them the water dripping from the roof had left film after film of carbonate of lime upon the floor, which was the centuries went by became a layer of stalagmite many feet thick sealing down the secrets of the past.

**********

The face of the country was now entirely changed. The glaciers were gone, and so, too, were all the strange animals. True, the reindeer, the wild ox, and even here and there the Irish elk, were still feeding in the valleys; wolves and bears still made the country dangerous, and beavers built their dams across the streams, which were now much smaller than formerly, and flowed in deeper channels, carved out by water during the interval. But the elephants, rhinoceroses, lions and tigers were gone never to return, and near the caves in which some of the people lived, and the rude underground huts which formed the homes of others, tame sheep and goats were lying with dogs to watch them. Again, though the land was still covered with dense forests, yet here and there small clearings had been made, where patches of corn and flax were growing. Naked children still played about as before, but now they were moulding cups of clay like those in which food was being cooked on the fire outside the caves or huts. Some of the women, dressed partly in skins of beasts, partly in rough woven linen, were spinning flax into thread, using as a spinning-whorl a small round stone with a hole in the middle tied to the end of the flax, as a weight to enable them to twirl it. Others were grinding corn in the hollow of a large stone by rubbing another stone with it.

The men, while they still spent much time in hunting, had now other duties in tending the sheep and goats, or looking after the hogs as they turned up the ground in the forest for roots, or sowing and reaping their crops. Yet still all the tools were made of stone, no longer rough and merely chipped like the old stone weapons, but neatly cut and polished. Stone axes with handles of deer-horn, stone spears and javelins, stone arrow-heads beautifully finished, sling-stones and scrapers were among their weapons and tools, and with them they made many delicate implements of bone. On the broad lakes which here and there broke the monotony of the forests, canoes, made of the trunks of trees hollowed out by fire, were being paddles by one man, while another threw out his fishing line armed with delicate bone-hooks; and on the banks of the lakes, nets weighted with drilled stones tied on to the meshes were dragged up full of fish.

For these Neolithic men, or men of the New Stone Period, who used polished stone weapons, were farmers, and shepherds, and fishermen. They knew how to make rude pottery, and kept domestic animals. Moreover, they either came from the east or exchanged goods by barter with tribes living more to the eastward, now that canoes enabled them to cross the sea. For many of their weapons were made of greenstone or jade, and of other kinds of stone not to be found in Europe, and their sheep and goats were animals of eastern origin. They understood, how to unite to protect their homes, for they made underground huts by digging down several feet into the ground and roofing the hole over with wood coated with clay; and often long passages underground united these huts, while in many places on the hills camps, made of ramparts of earth surrounded by ditches, served as strongholds for the women and children and the flocks and hers, when some neighbouring tribe attacked their homesteads.

Still, however, where caves were ready to hand they used them for houses, and the same shelter which had been the home of the ancient hunters now resounded with the voices of the shepherds, who, treading on the sealed floor, little dreamt that under their feet lay the remains of a bygone age.

And now, as the Professor watched this new race of men fashioning their weapons, feeding their oxen, and hunting the wild stage, his attention was arrested by a long train of people crossing a neighbouring plain, weeping and wailing as they went. At the head of this procession, lying on a stretcher made of tree-boughs, lay a dead chieftain, and as the line moved on, men threw down their tools, and women their spinning, and joined the throng. On they went to where two upright slabs or stone with another laid across them formed the opening to a long mound, or chamber. Into this the bearers passed lighted by torches, and in a niche ready prepared placed the dead chieftain in a sitting posture with the knees drawn up, placing by his side his flint spear and polished axe, his necklace of shells, and the bowl from which he had fed. Then followed the funeral feast, when with shouts and wailing fires were lighted, and animals slaughtered and cooked, while the chieftain was not forgotten, but portions were left for his use, and then the earth was piled up again around the mouth of the chamber, till it should be opened at some future time to place another member of his family by his side, or till in after ages the antiquary should rifle his resting-place to study the mode of burial in the Neolithic or Polished Stone Age.

Time passed on in the Professor’s dream, and little by little the caves were entirely deserted as men learnt to build huts of wood and stone. And as they advanced in knowledge they began to melt metals and pour them into moulds, making bronze knives and hatchets, swords, and spears; and they fashioned brooches and bracelets of bronze and gold, though they still also used their necklaces of shells, and their polished stone weapons. They began, too, to keep ducks and fowls, cows and horses, they knew how to weave in looms, and to make cloaks and tunics, and when they buried their dead it was no longer in a crouching position. They laid them decently to rest, as if in sleep, in the barrows where they are found to this day with bronze weapons by their side.

Then as time went on they learnt to melt even hard iron, and to beat it into swords and ploughshares, and they lived in well-built huts with stone foundations. Their custom of burial, too, was again changed, and they burnt their dead, placing ashes in a funeral urn.

By this time the Britons, as they were now called, had begun to gather together in villages and towns, and the Romans ruled over them. Now when men passed through the wild country they were often finely dressed in cloth tunics, wearing arm rings of gold, some even driving in war-chariots, carrying shields made of wickerwork covered with leather. Still many of the country people who laboured in the field kept their old clothing of beast skins, they grew their corn and stored it in cavities of the rocks, they made basket-work boats covered with skin, in which they ventured out to sea. So things went on for a long period till at last a troubled time came, and the quiet valleys were disturbed by wandering people who fled from the town and took refuge in the forests. For the Romans after 350 years of rule had gone back home to Italy, and a new and barbarous people called the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, came over the sea from Jutland and drove the Britons from their homes.

And so once more the caves became the abode of man, for the harassed Britons brought what few things they could carry away from their houses and hid themselves there from their enemies. How little they thought as they lay down to sleep on the cavern floor that beneath them lay the remains of two ages of men! They knew nothing of the woman who had dropped her stone spindle-whorl into the fire, on which the food of Neolithic man had been cooking in rough pots of clay; they never dug down to the layer of gnawed bones, nor did they even in their dreams picture the hyæna haunting his ancient den, for a hyæna was an animal they had never seen. Still less would they have believed that at one time, countless ages before, their island had been part of the continent, and that men, living in the cave where they now lay, had cut down trees with rough flings, and fought with such unknown animals as the mammoth and the sabre-toothed tiger.

But the Professor saw it all passing before him, even as he also saw these Britons carrying into the cave their brooches, bracelets, and finger rings, their iron spears and bronze daggers, and all their little household treasures which they had saved in their flight. And among these, mingling in the heap, he recognised Roman coins bearing the inscription of the Emperor Constantine, and he knew that it was by these coins that he had, a few days before in Yorkshire, been able to fix the date of the British occupation of a cave.

*******

And this this his dream ended, and he found himself clutching firmly the horn on which Palæolithic man had engraved the figure of the reindeer. He rose, and stretching himself crossed the sunny grass plot of the quadrangle and entered his classroom. The students wondered as he began his lecture at the far-away look in his eyes. They did not know how he had passed through a vision of countless ages; but that afternoon, for the first time, they realized, as he unfolded scene after scene, the history of “The Men of Ancient Days.”

Word Count: 3849

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Isaac Robertson

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

29 September 2020

Last modified

17 January 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | The caves of the Dordogne in southwestern France house prehistoric art; the Engis and Engihoul caves in Belgium were thought to have housed proto-human skeletons; “Hartz Mountains” most probably refers to the Harz mountain range in Germany, which is known as a former hunting ground for prehistoric man. |

|---|

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.