The Unicorn, A Story for Children

The Strand Magazine, vol. 9, issue 3 (1895)

Pages 346-357

Introductory Note: Written by E. P. Larken, “The Unicorn,” is a children’s story of three impoverished brothers’ attempts to find sparkling golden water which can transform objects to gold. The story employs many fairy tale traditions and tropes throughout the narrative in order to teach the lesson that kindness and generosity pay off in the end.

Advisory: This story depicts slavery and child-on-child abuse.

Fritz, Franz, and Hans were charcoal-burners. They lived with their mother in the depths of a forest, where they very seldom saw the face of another human being. Hans, the youngest, did not remember ever having lived anywhere else, but Fritz and Franz could just call to mind sunny meadows, in which they played as little children, plucking the flowers and chasing the butterflies. Indeed, Fritz was able to compare the present state of miserable poverty in which they lived with the ease and comfort they enjoyed in years gone by.

Once upon a time they were well off. They had enough to eat every day, they lived in a comfortable house, surrounded by a nice garden, and with plenty of kind neighbours round them. Then came a change. Their father lost his money, and was forced to leave this pleasant home, and to earn bread for his family by becoming a charcoal-burner. Everything now became different. Their house was a poor hut, composed of a few logs of wood knocked roughly together. Dry black bread with, occasionally, a few potatoes and lentils, and now and then, as a great treat, a little porridge, formed their food. And to secure even this they had to work hard from morning till night at their grimy trade. But their father was brave and patient, and, while he was alive, the wolf was kept some distance from the door. Besides, he could always put some heart into the boys, when they began to flag, by a joke or a pleasant story. But he had died a year ago, owing to an accident he met with while chopping wood for the furnace, and since his death matters had been going from bad to worse with the family.

Fritz and Franz were, unfortunately, selfish, ill-conditioned lads, who made the worst instead of the best of their troubles, and who even grudged their mother and brother their share of the food. Hans, on the other hand, was a capital fellow. He always had a cheerful smile or word, and did all in his power to help his mother to keep in good spirits. One day at dinner time they were startled by a knock at the door. A knock at the door does not sound to us, perhaps, to be a very startling thing, but they, as I said, so seldom saw a strange face near their home that this knock at the door quite took away their breath. When it came, Fritz and Franz were sitting over the fire munching their last piece of black bread, and grumbling to one another as was their custom, while Hans, seated on the bed beside his mother, was telling her about what he saw and what he fancied when he was in the forest. Fritz was the first to recover himself, and he growled out, in his usual surly tone, “Come in.” The door opened, and a gentleman entered. From his green dress, the gun that he carried in his hand, and the game-bag slung by his side, they saw that he was a huntsman who had been amusing himself with shooting the game with which the forest abounded.

“Good morning, good friends,” he said, in a cheerful tone. “Could you provide me with a cup of water and a mouthful of something to eat? I have forgotten to bring anything with me, and am ravenously hungry and far from home.”

Fritz and Franz first threw a scowling glance from under their eyebrows at the stranger, by way of reply, gave a grunt, and continued munching at their hunks of bread. Hans, however, was more polite. The only seats in the hut were occupied by Fritz and Franz, and, as they showed no disposition to move, Hans dragged a log of wood from a corner and placed it before the visitor and invited him to sit down. Then he produced a cup, scrupulously clean, indeed, but sadly cracked and chipped, and, running outside, he filled it from a spring of delicious cool water, which rose near the hut. As he had been busy talking to his mother, he had had no time to eat his share of the black bread, and so he handed his coarse crust to the stranger, saying he was sorry that there was nothing better to offer him.

“Thank you,” said the stranger, courteously. “Hunger is the best sauce. There is no lunch I like so well as this.” And he set to work with such a good will that in a very short time, poor Hans’ crust had vanished, and there was nothing left before the stranger but a few crumbs of bread on the table, and a few drops of water in the cup. These he kneaded carelessly together into a little pellet, about the size of a pea, while Hans told him, in answer to his questions, all about their lonely life in the forest, and the hardships which they had to endure.

When the stranger rose to go he said, “Well, I thank you heartily for your hospitality—now I will give you a word of advice. One of you lads should go and seek the sparkling golden water which turns everything it touches into gold.”

Fritz and Franz pricked up their ears at this, and, both at once, demanded where this sparkling golden water was to be found. The stranger turned towards them courteously, although these were the first words they had spoken since his entrance, and replied:—

“The sparkling golden water is to be found in the forest of dead trees, on the further side of those blue mountains which you may see on any clear day in the far distance. It is a three weeks’ journey on foot from here.”

Then, bowing to his hosts, he stepped towards the door. Hans, however, was there first, and opened it for him. Obeying a sign from the stranger, Hans followed him a little way from the hut. Then the stranger, taking from his pocket the little black bread pellet, said, “I know, because you gave me your dinner, that you will have to go hungry. I have no money to offer you, but here is something that will be of far greater value to you than money. Keep this pellet carefully, and when you seek this sparkling golden water, as I know you will, don’t forget to bring it with you. Now go back: you must follow me no further.” So saying, the stranger waved his hand to Hans, and plunging into the thicket, disappeared. Hans slipped the pellet into his pocket and re-entered the hut, where he found his brothers in loud dispute about the sparkling golden water. They were much too interested in the matter to pay any attention to Hans or to ask him, as he was afraid they would, whether the stranger had given him any money before he left. As he came in he heard Fritz saying, in a loud voice:—

“I’m the eldest, and I will go first to get the sparkling golden water. When I’ve got it I will buy all the land hereabouts and become Count. I will hunt every day, and have lots of good wine, and sometimes, if I’m passing near here, I’ll just look in to see how you all are, and to show you my fine clothes, and horses, and dogs, and servants.” Fritz was, for him, almost gracious at the bright prospect before him.

“I don’t care whether you’re the eldest or not,” growled Franz, stubbornly, “I shall go, too, to find the sparkling golden water. When I’ve found it I will buy the Burgomaster’s office, and live in his house in the town yonder, and wear his fur robes and gold chain, and, best of all, walk at the head of all the grand processions.1A “burgomaster” is a town official comparable to a mayor. None of your wild hunting for me—give me ease and comfort.”

At last it was decided, after a great deal of squabbling, that Fritz as the eldest should go first in search of the sparkling golden water, and accordingly next day he set out. Hans ventured to hint that the first thing to be done with this sparkling golden water when it was found should be to provide a comfortable home for their mother, but Fritz’s only answer to this was a blow, and an angry order to Hans to mind his own business.

We cannot follow Fritz all the way on his journey. As he had no money, he was forced to beg at the doors of the cottages and farm-houses which he passed, for food and shelter for the night. Now, this proved to be rather hard work, because nobody very much liked his looks or his manner, and people only gave him spare scraps now and then in order to get him to go away as soon as possible. However, he found himself, at last, approaching the forest of dead trees. He knew that it was the forest, although there was nobody there to tell him so. He had not, in fact, seen any human being for the last three days. But he felt that he could not be mistaken. A vast forest of enormous trees lifted leafless, sapless branches to the sky, which every breath of wind rattled together like the bones of a skeleton. When he was about twenty yards from the forest a terrible sound came from it. It was as though a thousand horses were neighing and screaming all at once. Fritz’s heart stood still. He wanted to run away, but his legs refused to move. As he stood there, shaking and quaking, there rushed out of the forest a huge unicorn with a spiral golden horn on his forehead.

“What seek you here?” asked the unicorn, in a voice of thunder. Fritz stammered out that he sought the sparkling golden water.

“What want you with the sparkling golden water, which is in my charge?” thundered the unicorn.

Fritz was almost too frightened to speak. He fell on his knees, put up his hands, and cried: “Oh, good Mr. Unicorn, oh, kind Mr. Unicorn, pray don’t hurt me.”

The unicorn stamped furiously on the ground with his right fore-foot. “Say this instant,” he cried, “what it is that you want with the sparkling golden water!”

“I want to get money to buy land and become a Count,” Fritz was just able to gasp out. The Unicorn said nothing: he simply lowered his head, and with his golden horn tossed Fritz three hundred and forty-five feet in the air. Up went Fritz like a sky-rocket, and down he came like its stick, turning somersaults all the way. Fortunately for him, his fall was broken by the branches of one of the dead trees. If it had not been for this he would probably have been seriously hurt. Through these branches he crashed until he reached the point where they joined the trunk. The tree was hollow here, and Fritz tumbled down to the bottom of the trunk and found himself a prisoner. While he was feeling his arms and legs to find out if any bones were broken or not, he had the satisfaction of hearing the unicorn, as he trotted back into the forest, muttering, loud enough for his words to pierce the bark and wood of Fritz’s prison:—

“So much for you and your Countship.”

Fritz tried to get out, but in vain. The tree was too smooth and slippery and high for him to be able to clamber up, and he only hurt himself every time he attempted to escape. There was nothing for it, then, but for him to lie down and howl. He had to satisfy his hunger, as best he might, by eating the stray worms and woodlice and fungi, which he found creeping, crawling, and growing round about the roots of the tree. We will leave him there for the present and return to the others.

Franz, Hans, and their mother waited and waited for Fritz to come back. Hans and his mother could not believe it possible that, when he had secured the sparkling golden water, he would leave them in their poverty. Franz, on the other hand, judging Fritz by himself, thought that nothing was more likely. And Franz was most probably right. Six weeks was the shortest time in which Fritz could be home again. “Unless,” said Hans, “he buys a horse and rides back, as he will be very well able to do when he has got the sparkling golden water.” But six weeks passed, and two months, and three months, and no Fritz, either on horseback or afoot. Then Franz’s patience came to an end. He must needs go, too.

“I won’t wait here starving any longer,” said he; “Fritz has forgotten all about us. I’ll get the sparkling golden water and become Burgomaster.” So off he set, following the same road as Fritz, and meeting with much the same difficulties. They were, however, rather greater in his case than in his brother’s. Folk remembered the ill-conditioned Fritz only too well, and Franz was so like him in looks and manner, that they shut the door in his face the moment he appeared, and ran upstairs and called out from the top windows of their houses, “Go away. There’s nothing for you here. The big dog’s loose in the yard. Go away, charcoal-burner.”

However, by dint of perseverance, in which to say the truth he was not lacking, Franz, very hungry and sulky, reached the verge of the forest of dead trees. Out came the unicorn and asked his business. On Franz replying that he wanted the sparkling golden water in order to buy the house and post of Burgomaster, the unicorn tossed him into the air, and he tumbled into the same tree as Fritz. Then the unicorn trotted back into the forest muttering, for Franz’s benefit: “So much for you and your Burgomastership.”

When Fritz and Franz found themselves thus closely confined in the same prison, they, instead of making the best of one another’s company, as sensible brothers would have done, fell to quarrelling and fighting, until at last neither would speak to the other, and that state of sulky silence they maintained all the time of their captivity.

The months passed by, but no news came to Hans and his mother of Fritz and Franz. Meanwhile Hans found that it became daily more difficult for him to earn enough money to support two people. Moreover, he saw that his mother was growing weaker, and he feared that she would die unless she had proper food and nourishment. At last he said:—

“Mother, if there was only someone to take care of you, I would go in search of Fritz and Franz. You may be sure that they have got the sparkling golden water by this time. They would never refuse me a few guldens if I were to ask them and tell them how ill you are.”

But Hans’ mother did not at all like the idea of his leaving her, and she begged and prayed him not to go. He felt obliged, therefore, to submit, and stayed on for a little longer, until at last even his mother saw that they must either starve or do as Hans suggested. Most fortunately at this time there dropped in to see them another charcoal-burner, whom Hans used to call “Uncle Stoltz,” although he was no uncle at all, but only a good-natured neighbor and an old friend of Hans’ father. Uncle Stoltz strongly urged the mother to let her boy go in search of his brothers, adding, although he was nearly as poor as they were themselves:—

“You come and live with me and my wife. While we have a crust to divide you sha’n’t want.”

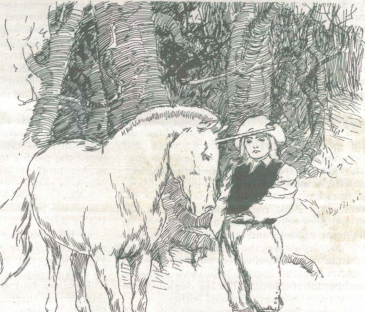

So Hans’ mother gave a reluctant consent, and went to live with Uncle Stoltz, while Hans went out in search of his brothers. By making inquiries he easily found the road which they had taken, but nobody ever thought of shutting the door in his face. On the contrary, his polite manners and cheerful looks made him a welcome guest at every cottage and farmstead at which he stopped. At last he, too, found himself on the verge of the forest of dead trees and face to face with the golden-horned unicorn. But Hans was not to be frightened as his brothers had been by the terrible voice and awe-striking appearance of the guardian of the fountain. In reply to the usual question—given in the usual tone of thunder: “What seek you here?”—Hans replied, coolly, “I seek my brothers, Fritz and Franz.”

“They are where you will never find them,” said the unicorn, “so go home again.”

“If I cannot find my brothers,” said Hans, firmly, “I will not go home without the sparkling golden water.”

“What want you with the sparkling golden water, which is in my charge?” asked the unicorn, in his terrible voice.

“I want to buy food and wine and comforts for my mother, who is very ill,” answered Hans, undaunted. But his eyes filled with tears as he thought of his mother.

The unicorn spoke more gently.

“Have you,” he asked, “the crystal ball? Because without it I cannot allow you to pass to the sparkling golden water.”

“The crystal ball!” echoed Hans. “I never heard of such a thing.”

“That’s a pity,” said the unicorn, gravely; “I’m afraid you will have to go home without the water; but, stay, feel in your pockets. You may have had the ball, and put it somewhere, and have forgotten all about it.”

Hans smiled at the idea of the crystal ball lying, unknown to him, in his pockets, but he followed the suggestion of the unicorn, and found, as he knew he should find, nothing at all, except, indeed, the pellet of black bread which the stranger-huntsman had given him, and which he had not thought of from that day to this. “No,” he said to the unicorn, “I have nothing in my pocket, except this pellet,” and he was about to throw it away when the unicorn called out to him to stop.

“Let me see it,” he said. “Why,” he went on, “this is the crystal ball—look!”

Hans did look, and sure enough he found in his hand a tiny globe of crystal. He examined it with amazement. “Well,” he said, “all I know is that a second ago it was a black bread pellet.”

“That may be,” said the unicorn, carelessly; “anyhow, it is a crystal ball now, and the possession of it makes me your servant. It is my duty to carry you to the fountain of sparkling golden water, if you wish to go. Have you brought a flask with you?”

“No,” said Hans. “Fritz took the only flask we had, and Franz an old bottle.”

“Fritz, eh? Well, follow me a little way.” So saying, the unicorn led Hans to the tree in which his brothers were imprisoned and, motioning him to be silent, cried out:—

“Ho! Master Count, throw out the flask you have with you, if you please: it is wanted.”

“Sha’n’t,” growled Fritz’s voice in reply, “unless you promise to let me out.”

“Oh, you won’t, won’t you?” said the unicorn; “well, we’ll see.”

With that he drew back a few steps, and then, running forwards, thrust his sharp horn into the side of the hollow trunk from which Fritz’s voice had issued. A loud yell came from the spot, showing that the horn had run into some tender part of Fritz’s body, and at the same instant, the flask appeared flying out of the hole of the tree by which Fritz and Franz had entered.

“That’s right,” said the unicorn, “now we shall do comfortably. Get on my back, grasp my mane tightly, hold your breath, and shut your eyes.”

“If you please,” said Hans, “will you set Fritz and Franz free first?”

The unicorn looked annoyed. “They are doing very well there,” he said; “why should you disturb them? But you’re my master, and I must do as you please. Only take my word you’ll be sorry for this afterwards.”

With that he went to the tree and, with one or two powerful blows with his horn, made a hole large enough for the unhappy prisoners to creep out. Two more sheepish, miserable wretches than those half-starved brothers of his, Hans had never seen. They fell at his feet and thanked him again and again for delivering them. They promised never to do anything unkind or selfish again, and each assured Hans that he had always liked him far more than he had liked the other brother.

Their protestations of affection rather disgusted Hans, only, as he was a good-hearted boy himself, he could not help being moved by them. He then told his brothers in what state he had left his mother, and how he was to be taken by the unicorn to get the sparkling golden water.

“Oh!” cried the brothers, “can’t you take us, too?”

The unicorn thought it time to interfere. “No one can be taken there, but the owner of the crystal ball,” he said. “Come, master, it is time for you to mount.”

Hans clambered nimbly into his seat on the unicorn’s back. “Wait for me here,” he called out to his brothers. “I shall not be long.” Then Hans shut his eyes, held his breath, and grasped the unicorn tightly by the mane. It was as well that he did so, for the unicorn gave a bound that carried him over the tops of the highest trees, and would certainly have thrown him off unless he had been very firmly seated. Three such bounds did he take, and then he paused and said to Hans, “Now you may open your eyes.” Hans found himself in a desolate, rocky valley, without a trace of vegetation—unless the forest of dead trees, which clothed the valley on every side, might be taken as vegetation. In the midst of the valley there sprang up a fountain of water, which sparkled with such intense brilliancy that Hans was unable at first to look upon it.

“There, master,” said the unicorn, turning his head, “this is the fountain of sparkling golden water. Dismount and fill your flask. But take care that you do not allow your hand to touch the water. If it does, it will be turned into gold and will never become flesh and blood again.”

Hans slipped from his seat and, flask in hand, approached the fountain. The ground on which he walked was sand, but as he drew nearer the fountain, he noticed that the sand kept growing brighter until he felt that he was walking upon what he guessed rightly to be veritable gold dust. Hans thrust a handful of this dust into his pocket, and also one or two moderate-sized stones that he found, which, like the sand, had been changed, by the spray coming from the fountain, into pure gold. He tried to be as careful as possible in filling the flask; but, notwithstanding all his care, the top joint of his little finger touched the water, and in an instant became gold. However, he had his flask full of sparkling golden water, the flask itself now of course golden, and he felt that the top joint of his little finger was a small price to pay for all this.

“Now, master,” said the unicorn, when Hans got back, “do you still intend to return to those brothers of yours? Or shall I put you out of the forest at some other point?”

“Certainly,” replied Hans; “I intend to return to them. You heard them say how sorry they were for all the unkindness they had shown to my mother and me. I know they mean to do better for the future. Besides, I promised them to come back.”

The unicorn said nothing but grunted, in an unencouraging manner, and motioned to Hans to get on his back. When he was seated the unicorn said:—

“Since this is your wish, you must have it. I have, however, three pieces of advice to give you: On your way home your brothers will offer to carry the flask—do not let them do so; also, do not let them get behind you for a moment; and, thirdly, guard the crystal ball with the utmost care. I can’t go with you beyond the verge of the forest of dead trees. One visit, and only one, is permitted to the fountain. You therefore can never come here again. But if ever you need me sorely, crush the crystal ball, and I will be with you. Now shut your eyes, we must be off.”

Three bounds brought them to the side of Fritz and Franz, and Hans having thanked the unicorn warmly for his kindness, the three brothers began to retrace their steps homewards. Now, during Hans’ absence at the fountain, Fritz and Franz had been devising how they might rob him of the flask of sparkling golden water

“It is disgusting,” they said to one another, “that this wretched little Hans should beat us both. He will only waste the water in buying things for his mother, while it would make us Count and Burgomaster.”

As soon, therefore, as they were out of sight of the unicorn, Fritz and Franz begged and prayed Hans to allow one of them to carry the flask.

“You’ve had all the trouble of getting the water,” they said, “we ought at least to be allowed the honour of helping you to carry it. Besides, are we not your servants now that you are so rich? It is not suitable for you to do all the work.” But Hans remembered the unicorn’s words, and held firmly to his flask.

“No,” he said, “thank you; but I’ll carry it myself.” Then Fritz and Franz pretended to get sulky and tried to drop behind, but Hans would not allow this either. The consequence was, that the three made very slow progress homeward. Towards the evening they came to a deep stream, which they had to recross. It was only fordable at one point, as they all knew, because they had, of course, already crossed it before. Hans stood aside to allow Fritz and Franz to go on first, but each of them went in a little way, and ran back, saying that they were afraid of being drowned.

“What nonsense,” said Hans, who was getting a little impatient at the delay. “It’s quite shallow,” and, forgetting the unicorn’s warning, he entered the stream first. Fritz and Franz did not miss the opportunity. Each took a large stone and struck Hans violently on the head. Then as he fell back senseless into the water, Fritz snatched the flask from off his belt to which it was attached, and Franz thrust with his foot Hans’ body further into the river, so that the current should carry it away, and, laughing at their own cleverness, the two proceeded to cross the ford. Now, naturally enough, people like Fritz and Franz do not care to trust one another very far.

As soon, therefore, as they reached the other side of the stream, Franz produced his bottle, and demanded of Fritz his share of the sparkling golden water. Fritz, who intended to keep it all himself, proposed that they should put off sharing it till later. Franz would not hear of this. He knew, only too well, what Fritz was up to. This led to a wrangle, which ended in a fight between the two, in which the sparkling golden water was spilled, partly over Fritz’s right hand, and the remainder over Franz’s left foot. The brothers first realized what had happened to them by Fritz finding that he could not close his fist to strike, and Franz finding that he could not raise his foot to kick. The discovery sobered them in an instant. There they stood, one with a hand and the other with a foot of solid gold, and the golden flask with them; but the water, the precious sparkling golden water, lost for ever. Fritz was the first to recover himself.

“Well,” he said, “thank goodness I have a couple of feet left me. I shall be off, I can’t wait for you. You must hobble on as best you can, or stay here and starve,” and he was on the point of leaving Franz to his fate, when the latter caught him by the collar.

“If I’ve only one foot I have two hands,” cried he, “and I don’t intend to let you leave me behind. No, no, we must go together or not at all.”

Fritz was obliged to submit, as it was a case of two hands against one, and he and Franz, arm in arm, as though they were the most affectionate brothers, made their way slowly to the nearest town. There they had to submit to have hand and foot cut off. The operation hurt them very much indeed, but they sold the gold for a good sum of money to the goldsmith. With that, and with what they got for the flask, Fritz was able to buy his Countship, although he could never hunt owing to the loss of his right hand, and Franz was able to buy his Burgomastership, although the loss of his foot prevented his walking properly in processions. Neither of them gave a thought to their mother.

Now we must return to poor Hans, whom we left floating down the stream—senseless, and to all appearance dead. He was not dead, however, although the blows which his brothers had inflicted were very severe ones. He was only stunned, and fortunately he did not float far enough to be drowned. His body came into a back eddy of the stream and drifted gently on to a shelving bank of white sand. The cold water soon had the effect of bringing him to his senses so far as to enable him to crawl on to the land. It was, however, some hours before he was able to recall these past events. When he remembered them he gave way to despair. All the pains he had taken to win the sparkling golden water were thrown away. He might not return to get more—the unicorn had told him that. His mother would be as badly off as ever. Above all, he had the bitter disappointment of feeling that his brothers had deceived him. Then he bethought him of the crystal ball. Taking it from his pocket, he placed it on a large stone, and taking another stone struck it with all his force. A report like that of a cannon followed, and at the same instant the unicorn stood before him.

“I warned you of what would happen,” he said to Hans. “You would have done much better if you had left your brothers in the tree. Now let me see what can be done for you. First of all, rub that dockleaf, which is touching your right hand, on the wound in your head.” Hans did as he was told, and his head became as sound as ever. “Now,” said the unicorn, “you must go straight home to your mother and bring her to the city of White Towers, and stay there till you hear from me again.”

“But,” said Hans, with tears in his eyes, “how can I do this? My mother is much too ill to move, and I have lost the sparking golden water which was to have made her well and strong.”

“Did not I see you,” asked the unicorn, “put some sand and stones of pure gold into your pocket as you went to the fountain? There will be more than enough to meet all your expenses. Do as I tell you,” and the unicorn, saying this, disappeared.

Hans, greatly cheered, set off once more and finished his journey home without any further adventures. The gold that he had with him not only enabled him to provide the comforts and necessaries which his mother required, but he was also able to reward Uncle Stoltz for his kindness. When his mother was strong enough to travel, Hans hired a waggon, and they set off by easy stages for the city of White Towers, there to await further news from the unicorn.

Now, the city of White Towers was at that time attracting from far and wide everyone who wanted to make his fortune. The Princess of the city was the loveliest Princess in the world, and the richest and the most powerful. She had given out that she would marry anyone, whoever it might be, king or beggar, who would tell her truly in the morning the dreams that she had dreamed in the night. But whoever should compete and fail was to forfeit all his fortune, be whipped through the streets and out of the city gate, and banished from the town on pain of death. If, however, he had no fortune to forfeit, he was to be whipped back again and sold into slavery. The terms were hard, but many tried and failed, and many more, undeterred by this punishment which they constantly saw being inflicted on the others, were waiting their turn to compete. Among these latter were Count Fritz and Burgomaster Franz. These two met very often in the streets of the city, but they could never forget their quarrel over the sparkling golden water, and when they met they always looked in opposite directions. Now, Fritz and Franz had made themselves hated by all with whom they had to deal: Fritz by his tyranny over the poor in the district in which his property lay, and Franz by his injustice as Burgomaster. The former used to grind down his people so as to extract the last penny from them. The latter used to make his judgments depend on the amount of bribe he received from the suitors. Everybody, therefore, hoped that both Fritz and Franz would fail to tell the Princess her dreams, and would have to pay the penalty.

Hans and his mother arrived at the city of White Towers on the evening before the day on which Fritz was to try his fortune. They heard on all sides that the “one-armed Count,” as he was called, so generally detested, was to be the next competitor, but, of course, they had no idea that this “one-armed Count” was Fritz. The consequence was that when they found themselves next day in the great square, where the whole population of the city assembled to see the trial, they were amazed beyond measure to see Fritz marching jauntily along, quite confident of success, dressed in his very smartest clothes, to the platform on which the Princess and her ladies and her courtiers were assembled. Fritz felt sure that he would win for this reason: There was an old woman living in a cottage near his castle, who was said to be a witch. Fritz had ordered her to be seized and put to the most cruel tortures, in order to force her to say what the Princess was going to dream on the night before the day fixed for his trial. This was very silly of him, as the old woman might be a witch ten times over, and yet not be able to tell him that. But cruel, wicked people often are silly. This poor old woman screamed out some nonsense in her agony, which Fritz took to be the answer he required. He smiled, therefore, in a self-confident fashion as he bowed low before the Princess and awaited her question. She asked it in a clear, bell-like voice, which somehow caused Hans’ heart, when he heard it, to beat a good deal quicker than before.

“Sir Count—what did I dream last night?”

“Your Highness dreamt,” was the reply, “that the moon came down to earth and kissed you.”

The Princess gently shook her head, and in a moment Fritz found himself in the hands of her guards, with his coat stripped off his back, and his hands bound behind him. The first lash made him cry for mercy, but the Princess had already gone, and the soldiers, whose duty it was to inflict the whipping, were not much disposed to show mercy to the “one-armed Count.” They laid on their blows well, driving the unlucky Fritz through the streets till the gate was reached, through which, with a final shower of blows, he was thrust, with the warning not to return thither, but to beg his way henceforth through the world. Of all who watched the proceedings, none seemed so delighted with the result as Franz. He followed, hobbling after his unhappy brother as close as the soldiers would allow, and kept jeering and laughing at him all the way. This was easy for him to do, notwithstanding the fact that he had to go on crutches, because good care was taken to make Fritz’s progress through the streets as slow as possible. In addition, therefore, to the blows, Fritz had to endure the sight of Franz’s grinning face, and to listen to such remarks as: “Who thought he was going to win the Princess?”—“Will your Highness remember your poor brother the Burgomaster?”—“Who lost the sparkling golden water?”—and so on.

With very different feelings had Hans watched the proceedings. When he saw his brother stripped for beating, he forgot all about the wrongs he had sustained, and only thought what he could do to help the sufferer. He tried to bribe the soldiers to deal gently with Fritz, but when he found that that was of no avail, he hastened to the city gate so as to meet his brother outside and comfort him when the punishment was over. Hans found Fritz, as indeed was natural under the circumstances, more surly and ill-tempered than ever. He appeared startled for a moment at seeing Hans, whom he thought dead, alive and well, but he set to work blubbering again immediately, and rubbing his back with his one hand. Hans gave him what money he could afford, which Fritz took without saying “Thank you,” and went his way.

Next day it was Franz’s turn to try and win the Princess. Franz felt just as certain of succeeding as Fritz had been. A certain necromancer in Franz’s town had been a party in a suit which came before the Burgomaster’s court. All the evidence which was brought forward told against him, but the necromancer promised Franz, as a bribe, if he would decide in his favour, to tell him by means of his art the true secret of the Princess’s dream. Franz swallowed the bait greedily, and gave his unjust decision. Now, in order that the necromancer might not fail him, Franz had determined not to let him out of his sight till the day of trial. Very early in the morning of that day the necromancer came to Franz and said: “Last night the Princess dreamed so-and-so—will your worship allow me to go away now?” Franz on hearing the dream skipped with delight, forgetting about his foot, and tumbled down on the floor. However, he did not mind that, and gave the necromancer leave to depart, which the necromancer did in great haste. Franz was so impatient that he was in his place, in front of the platform, long before the Princess arrived. He could hardly wait for her to put the formal question before he blurted out:—

“Your Highness dreamt that you were walking in your garden, and that all the trees and shrubs bore gold and silver leaves.”

The Princess shook her head. “A very pretty dream,” she said, “but it was not mine.” So Franz had to suffer the same punishment as Fritz, and nobody was at all sorry. He was likewise thrust out at the city gate, bawling between his howls for someone to bring him the necromancer. Hans found him there, and tried to comfort him, as he had tried to comfort Fritz, and with about the same result. When Hans had got back to the inn where he and his mother were staying, he was met with the news that a stranger was waiting to see him. He went in and found the huntsman who had given him the pellet which turned into the crystal ball.

“Hans,” said the huntsman, as soon as Hans entered the room, “the unicorn has sent me to you. It’s your turn now to try to win the Princess.”

Hans turned pale at the thought.

“I would give my life to win her,” he said, earnestly; “but I am certain to fail, and then what will my poor mother do? I have no property to be confiscated, and, of course, I shall be sold into slavery.”

“Don’t talk of failure,” said the huntsman, cheerily; “the way to success is to forget that there is such a word as failure. Now I’ll tell you my plan. The Princess, as you know, or as you very likely don’t know, is devoted to curious animals of all kinds. I will change you into a white mouse with a gold claw, and will offer you to the Princess for sale. She has never seen or heard of such a creature as a white mouse with a gold claw before, and will be sure to buy you. Then it will be your fault if matters don’t go smoothly with you. You have only to keep your ears open and use your wits. Now, first of all, we must enter you for to-morrow’s competition.”

Hans longed to try his luck with the Princess, and as this plan seemed a promising one—indeed, it was the only one he could think of—he agreed to try it. However, he determined not to tell his mother anything about the matter, as he knew how terrified she would be at the thought of his failure. The first thing, as the huntsman had said, was for him to present himself to the Princess as candidate for her hand. He accordingly did so, and found her seated on her throne, surrounded by the lords and ladies of her Court, glittering in jewels and dressed in magnificent apparel. Hans felt rather shy as he marched up the splendid room, amongst all these grandly-dressed people, in his shabby old clothes; but he put as good a face on it as he could, and when he stopped before the throne and looked into the Princess’s eyes, all his shyness vanished. He was conscious of nothing but a strong determination to win her for himself or to perish in the attempt. The Court usher announced his name and purpose in a loud tone.

“This is Hans, the charcoal-burner, who has undertaken to tell the Princess her dream to-morrow morning, or to pay the penalty.”

When the Princess looked at Hans and saw what a nice, open-faced boy he was, she did all she could to persuade him to give up the attempt. She pointed out to him how many had tried and failed—how little chance there was of his succeeding. She could not bear, she said, to think of his being whipped publicly and sold into slavery. She offered him, if he would withdraw, the important post of general manager of the Court menagerie. But neither this offer nor the prayers of the Princess could move Hans.

“Now that I have seen you face to face, Princess,” said he, “I would rather die twenty times over than give up the undertaking.”

The Princess was obliged to allow Hans to enter his name for to-morrow’s trial, although it made her very unhappy. Her heart told her that he was the one of all her suitors whom she would most wish to succeed, but she felt that he would be certain to fare as the others had done; and so when the formality was over, and Hans had left, she dismissed the Court, shut herself up in her room, and said she would be at home to nobody for the rest of the day.

As soon as Hans got back, the huntsman took a cup of water, muttered some strange words over it, and sprinkled Hans with the contents. He was conscious of a curious change taking place in him, and before he could quite make out what it was, he found that he was a white mouse with a gold claw. The huntsman put him in a box and carried him to the palace to sell him to the Princess. When he arrived there the porter refused to admit him.

“No!” he said, “the Princess had given out that she would see no one that day. It was more than his place was worth to admit the stranger.” However, by dint of flattering words and a handsome present slipped into his hand, the porter was persuaded to send for one of the Princess’s ladies. When she came and saw the white mouse with the gold claw, she said she was sure that her mistress would be so delighted with this beautiful little curiosity, that she would pardon having her orders disobeyed for once. Only, the huntsman must remain where he was; she would take the white mouse to the Princess herself. To this the huntsman consented, and the long and short of it was that the Princess sent him a handsome sum for the mouse, and Hans found himself established as her newest favourite. The Princess was so pleased with her pet that, when she went to bed, she placed him in a cabinet in her room, the door of which she left open—because he was so tame that she had no fear of his attempting to run away. Hans was wondering how he was to find out the Princess’s dream in this situation, when his mistress woke up, laughing heartily, and called for her lady in waiting to come to her.

“I’ve had such a curious dream,” she said. “I dreamt that I was married to a man with a golden top-joint to his little finger. I suppose that it was the white mouse with the gold claw which put the idea into my head. But,” and here the Princess’s voice grew very sad, “how will that poor boy ever guess this dream to-morrow?”

Hans waited impatiently for all to be quiet, then he slipped out of his cabinet, and, finding the door shut, ran up the curtain of the window, which was fortunately open, and getting on a rose which clambered up outside the wall, ran down it and made the best of his way to the inn. There he found the huntsman waiting for him, to whom he told all that had taken place, and who in a few seconds changed him back to his own shape.

An enormous concourse of people were assembled next day to see the trial. Very pale and sad the Princess looked as she sat prepared to put the question to Hans. He waited respectfully till she had spoken, and then, without saying a word, held out his hand to her. Her eye fell on the golden top-joint of his little finger. She cried out with delight, and, seizing his hand in hers, turned to the people and said: “Hans has guessed right, and he shall be my husband.”

And all the people raised a glad shout, “Long live Prince Hans!”

“Oh!” said the Princess to Hans, “how I wish my brother were here to share our happiness.”

“He is here,” said the huntsman, who had thrust his way to the front; and, throwing off his huntsman’s disguise, he appeared dressed as a Prince. Then, turning to Hans, he said:—

“A mighty magician, the enemy of our family, condemned me, because I would not give him my sister in marriage, to take the form of a unicorn, and to guard the sparkling golden water. Twice every year, for a fortnight at a time, I was allowed to resume my human shape. It was then that I came to your hut in the forest and gave you the token by which to win your way to the fountain. The spell laid upon me was only to be raised when someone guessed aright my sister’s dream, and so won her to wife. Thanks to you, brother Hans, the magician’s power is at an end.”

Hans and the Princess were married, and after the ceremony the Prince went off to his own kingdom. Hans’ mother had a beautiful suite of apartments in the palace assigned to her, and Uncle Stoltz was not forgotten, but was provided for comfortably for life, and they all lived happily ever afterwards.

As for Fritz and Franz, they were so selfish and cruel, that there was nothing to be done with them but to send them back into the forest again to burn charcoal, and for all I know they are burning charcoal there still.

Word Count: 8518

Original Document

Topics

- Children’s literature

- Didactic literature

- Fairy tale

- Animals

- Fantasy fiction

- Love story/Marriage plot

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Edmund P. Larken. “The Unicorn, A Story for Children.” The Strand Magazine, vol. 9, no. 3, 1895, pp. 346-57. Edited by Natalie Hopkins. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 6 March 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-unicorn-a-story-for-children/.

Editors

Natalie Hopkins

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

27 January 2021

Last modified

5 March 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | A “burgomaster” is a town official comparable to a mayor. |

|---|