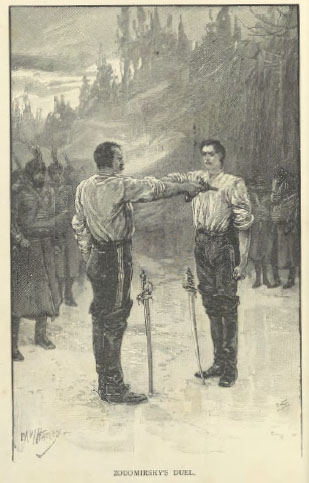

Zodomirsky’s Duel

The Strand Magazine, vol. 3, issue 6 (1892)

Pages 554-562

Introductory Note: Alexandre Dumas’s short story “Zodomirsky’s Duel” is the tale of a captain who reports to his new regiment for duty, only to be immediately challenged to a duel by another officer, Lieutenant Stamm. This translation of the story, originally written in French, was published in The Strand Magazine many years after the success of Dumas’ two most famous novels, The Three Musketeers, published in 1822, and The Count of Monte Cristo, published in 1844. Translations of a few other Dumas stories were published in The Strand Magazine, including “The Enchanted Whistle” in 1891 and “Marceau’s Prisoner” in 1892, just a month after “Zodomirsky’s Duel.”

The story of Captain Zodomirsky and his duel with Lieutenant Stamm is a suspenseful tale of jealousy, romantic love, and courage.

I.

AT the time of this story our regiment was stationed in the dirty little village of Valins, on the frontier of Austria.

It was the fourth of May in the year 182–, and I, with several other officers, had been breakfasting with the Aide-de-Camp in honour of his birthday, and discussing the various topics of the garrison.

“Can you tell us without being indiscreet,” asked Sub-Lieutenant Stamm of Andrew Michaelovitch, the aide-de-camp, “what the Colonel was so eager to say to you this morning?”

“A new officer,” he replied, “is to fill the vacancy of captain.”

“His name?” demanded two or three voices.

“Lieutenant Zodomirsky, who is betrothed to the beautiful Mariana Ravensky.”

“And when does he arrive?” asked Major Belayef.

“He has arrived. I have been presented to him at the Colonel’s house. He is very anxious to make your acquaintance, gentlemen, and I have therefore invited him to dine with us. But that reminds me, Captain, you must know him,” he continued, turning to me, “you were both in the same regiment at St. Petersburg.”

“It is true,” I replied. “We studied there together. He was then a brave, handsome youth, adored by his comrades, in everyone’s good graces, but of a fiery and irritable temper.”

“Mademoiselle Ravensky informed me that he was a skilful duellist,” said Stamm. “Well, he will do very well here; a duel is a family affair with us. You are welcome, Monsieur Zodomirsky. However quick your temper, you must be careful of it before me, or I shall take upon myself to cool it.”

And Stamm pronounced these words with a visible sneer.

“How is it that he leaves the Guards? Is he ruined?” asked Cornet Naletoff.

“I have been informed,” replied Stamm, “that he has just inherited from an old aunt about twenty thousand roubles. No, poor devil! he is consumptive.”

“Come, gentlemen,” said the Aide-de-Camp, rising, “let us pass to the saloon and have a game of cards. Koloff will serve dinner whilst we play.”

We had been seated some time, and Stamm, who was far from rich, was in the act of losing sixty roubles, when Koloff announced—

“Captain Zodomirsky.”

“Here you are, at last!” cried Michaelovitch, jumping from his chair. “You are welcome.”

Then, turning to us, he continued—“These are your new comrades, Captain Zodomirsky; all good fellows and brave soldiers.”

“Gentlemen,” said Zodomirsky, “I am proud and happy to have joined your regiment. To do so has been my greatest desire for some time, and if I am welcome, as you courteously say, I shall be the happiest man in the world.”

“Ah! good day, Captain,” he continued, turning to me and holding out his hand. “We meet again. You have not forgotten an old friend, I hope?”

As he smilingly uttered these words, Stamm, to whom his back was turned, darted at him a glance full of bitter hatred. Stamm was not liked in the regiment; his cold and taciturn nature had formed no friendship with any of us. I could not understand his apparent hostility towards Zodomirsky, whom I believed he had never seen before.

Someone offered Zodomirsky a cigar. He accepted it, lit it at the cigar of an officer near him, and began to talk gaily to his new comrades.

“Do you stay here long?” asked Major Belayef.

“Yes, monsieur,” replied Zodomirsky. “I wish to stay as long as possible,” and as he pronounced these words he saluted us all round with a smile. He continued, “I have taken a house near that of my old friend Ravensky whom I knew at St. Petersburg. I have my horses there, an excellent cook, a passable library, a little garden, and a target; and there I shall be quiet as a hermit, and happy as a king. It is the life that suits me.”

“Ha! you practise shooting!” said Stamm, in such a strange voice, accompanied by a smile so sardonic, that Zodomirsky regarded him in astonishment.

“It is my custom every morning to fire twelve balls,” he replied.

“You are very fond of that amusement, then?” demanded Stamm, in a voice without any trace of emotion; adding, “I do not understand the use of shooting, unless it is to hunt with.”

Zodomirsky’s pale face was flushed with a sudden flame. He turned to Stamm, and replied in a quiet but firm voice, “I think, monsieur, that you are wrong in calling it lost time to learn to shoot with a pistol; in our garrison life an imprudent word often leads to a meeting between comrades, in which case he who is known for a good shot inspires respect among those indiscreet persons who amuse themselves in asking useless questions.”

“Oh! that is not a reason, Captain. In duels, as in everything else, something should be left to chance. I maintain my first opinion, and say that an honourable man ought not to take too many precautions.”

“And why?” asked Zodomirsky.

“I will explain to you,” replied Stamm. “Do you play at cards, Captain?”

“Why do you ask that question?”

“I will try to render my explanation clear, so that all will understand it. Everyone knows that there are certain players who have an enviable knack, whilst shuffling the pack, of adroitly making themselves master of the winning card. Now, I see no difference, myself, between the man who robs his neighbour of his money and the one who robs him of his life.” Then he added, in a way to take nothing from the insolence of his observation, “I do not say this to you, in particular, Captain, I speak in general terms.”

“It is too much as it is, monsieur!” cried Zodomirsky, “I beg Captain Alexis Stephanovitch to terminate this affair with you.” Then, turning to me, he said, “You will not refuse me this request?”

“So be it, Captain,” replied Stamm quickly. “You have told me yourself you practise shooting every day, whilst I practise only on the day I fight. We will equalise the chances. I will settle details with Monsieur Stephanovitch.”

Then he rose and turned to our host.

“Au revoir, Michaelovitch,” he said. “I will dine at the Colonel’s.” And with these words he left the room.

The most profound silence had been kept during this altercation; but, as soon as Stamm disappeared, Captain Pravdine, an old officer, addressed himself to us all.

“We cannot let them fight, gentlemen,” he said.

Zodomirsky touched him gently on his arm.

“Captain,” he said, “I am a newcomer amongst you; none of you know me. I have yet, as it were, to win my spurs; it is impossible for me to let this quarrel pass without fighting. I do not know what I have done to annoy this gentleman, but it is evident that he has some spite against me.”

“The truth of the matter is that Stamm is jealous of you, Zodomirsky,” said Cornet Naletoff. “It is well known that he is in love with Mademoiselle Ravensky.”

“That, indeed, explains all,” he replied. “However, gentlemen, I thank you for your kind sympathy in this affair from the bottom of my heart.”

“And now to dinner, gentlemen!” cried Michaelovitch. “Place yourselves as you choose. The soup, Koloff; the soup!”

Everybody was very animated. Stamm seemed forgotten; only Zodomirsky appeared a little sad. Zodomirsky’s health was drunk; he seemed touched with this significant attention, and thanked the officers with a broken voice.

“Stephanovitch,” said Zodomirsky to me, when dinner was over, and all had risen, “since M. Stamm knows you are my second and has accepted you as such, see him, and arrange everything with him; accept all his conditions; then meet Captain Pravdine and me at my rooms. The first who arrives will wait for the other. We are now going to Monsieur Ravensky’s house.”

“You will let us know the hour of combat?” said several voices.

“Certainly, gentlemen. Come and bid a last farewell to one of us.”

We all parted at the Ravenskys’ door, each officer shaking hands with Zodomirsky as with an old friend.

II.

STAMM was waiting for me when I arrived at his house. His conditions were these—Two sabres were to be planted at a distance of one pace apart; each opponent to extend his arm at full length and fire at the word “three.” One pistol alone was to be loaded.

I endeavoured in vain to obtain another mode of combat.

“It is not a victim I offer to M. Zodomirsky,” said Stamm, “but an adversary. He will fight as I propose, or I will not fight at all; but in that case I shall prove that M. Zodomirsky is brave only when sure of his own safety.”

Zodomirsky’s orders were imperative. I accepted.

When I entered Zodomirsky’s rooms, they were vacant; he had not arrived. I looked round with curiosity. They were furnished in a rich but simple manner, and with evident taste. I drew a chair near the balcony and looked out over the plain. A storm was brewing; some drops of rain fell already, and thunder moaned.

At this instant the door opened, and Zodomirsky and Pravdine entered. I advanced to meet them.

“We are late, Captain,” said Zodomirsky, “but it was unavoidable.”

“And what says Stamm,” he continued.

I gave him his adversary’s conditions. When I had ended, a sad smile passed over his face; he drew his hand across his forehead and his eyes glittered with feverish lustre.

“I had foreseen this,” he murmured. “You have accepted, I presume?”

“Did you not give me the order yourself?”

“Absolutely,” he replied.

Zodomirsky threw himself in a chair by the table, in which position he faced the door. Pravdine placed himself near the window, and I near the fire. A presentiment weighed down our spirits. A mournful silence reigned.

Suddenly the door opened and a woman muffled in a mantle which streamed with water, and with the hood drawn over her face, pushed past the servant, and stood before us. She threw back the hood, and we recognised Mariana Ravensky!

Pravdine and I stood motionless with astonishment. Zodomirsky sprang towards her.

“Great heavens! what has happened, and why are you here?”

“Why am I here, George?” she cried. “It is you who ask me, when this night is perhaps the last of your life? Why am I here? To say farewell to you. It is only two hours since I saw you, and not one word passed between us of to-morrow. Was that well, George?”

“But I am not alone here,” said Zodomirsky in a low voice. “Think, Mariana. Your reputation—your fair fame—”

“Are you not all in all to me, George? And in such a time as this, what matters anything else?”

She threw her arms about his neck and pressed her head against his breast.

Pravdine and I made some steps to quit the room.

“Stay, gentlemen,” she said, lifting her head. “Since you have seen me here, I have nothing more to hide from you, and perhaps you may be able to help me in what I am about to say.”1Closing quotation mark added to mark the end of her speech. Then, suddenly flinging herself at his feet—

“I implore you, I command you, George,” she cried, “not to fight this duel with Monsieur Stamm. You will not end two lives by such a useless act! Your life belongs to me; it is no longer yours. George, do you hear? You will not do this.”

“Mariana! Mariana! in the name of heaven do not torture me thus! Can I refuse to fight? I should be dishonoured—lost! If I could do so cowardly an act, shame would kill me more surely than Stamm’s pistol.”

“Captain,” she said to Pravdine, “you are esteemed in the regiment as a man of honour; you can, then, judge about affairs of honour. Have pity on me, Captain, and tell him he can refuse such a duel as this. Make him understand that it is not a duel, but an assassination; speak, speak, Captain, and if he will not listen to me, he will to you.”

Pravdine was moved. His lips trembled and his eyes were dimmed with tears. He rose, and, approaching Mariana, respectfully kissed her hand, and said with a trembling voice—

“To spare you any sorrow, Mademoiselle, I would lay down my life; but to counsel M. Zodomirsky to be unworthy of his uniform by refusing this duel is impossible. Each adversary, your betrothed as well as Stamm, has a right to propose his conditions. But whatever be the conditions, the Captain is in circumstances which render this duel absolutely necessary. He is known as a skilful duellist; to refuse Stamm’s conditions were to indicate that he counts upon his skill.”

“Enough, Mariana, enough,” cried George. “Unhappy girl! you do not know what you demand. Do you wish me, then, to fall so low that you yourself would be ashamed of me? I ask you, are you capable of loving a dishonoured man?”

Mariana had let herself fall upon a chair. She rose, pale as a corpse, and began to put her mantle on.

“You are right, George, it is not I who would love you no more, but you who would hate me. We must resign ourselves to our fate. Give me your hand, George; perhaps we shall never see each other again. To-morrow! to-morrow! my love.”

She threw herself upon his breast without tears, without sobs, but with a profound despair.

She wished to depart alone, but Zodomirsky insisted on leading her home.

Midnight was striking when he returned.

“You had better both retire,” said Zodomirsky as he entered. “ I have several letters to write before sleeping. At five we must be at the rendezvous.”

I felt so wearied that I did not want telling twice. Pravdine passed into the saloon, I into Zodomirsky’s bedroom, and the master of the house into his study.

The cool air of the morning woke me. I cast my eyes upon the window, where the dawn commenced to appear. I heard Pravdine also stirring. I passed into the saloon, where Zodomirsky immediately joined us. His face was pale but serene.

“Are the horses ready?” he inquired.

I made a sign in the affirmative.

“Then, let us start,” he said.

We mounted into the carriage, and drove off.

III.

“AH,” said Pravdine all at once, “there is Michaelovitch’s carriage. Yes, yes, it is he with one of ours, and there is Naletoff, on his Circassian horse. Good! the others are coming behind. It is well we started so soon.”

The carriage had to pass the house of the Ravenskys. I could not refrain from looking up; the poor girl was at her window, motionless as a statue. She did not even nod to us.

“Quicker! quicker!” cried Zodomirsky to the coachman. It was the only sign by which I knew that he had seen Mariana.

Soon we distanced the other carriages, and arrived upon the place of combat—a plain where two great pyramids rose, passing in this district by the name of the “Tomb of the Two Brothers.” The first rays of the sun darting through the trees began to dissipate the mists of night.

Michaelovitch arrived immediately after us, and in a few minutes we formed a group of nearly twenty persons. Then we heard the crunch of other steps upon the gravel. They were those of our opponents. Stamm walked first, holding in his hand a box of pistols. He bowed to Zodomirsky and the officers.

“Who gives the word to fire, gentlemen?” he asked.

The two adversaries and the seconds turned towards the officers, who regarded them with perplexity.

No one offered. No one wished to pronounce that terrible “three,” which would sign the fate of a comrade.

“Major,” said Zodomirsky to Belayef, “will you render me this service?”

Thus asked, the Major could not refuse, and he made a sign that he accepted.

“Be good enough to indicate our places, gentlemen,” continued Zodomirsky, giving me his sabre and taking off his coat, “then load, if you please.”

“That is useless,” said Stamm, “I have brought the pistols; one of the two is loaded, the other has only a gun-cap.”

“Do you know which is which?” said Pravdine.

“What does it matter?” replied Stamm, “Monsieur Zodomirsky will choose.”

“It is well,” said Zodomirsky.

Belayef drew his sabre and thrust it in the ground midway between the two pyramids. Then he took another sabre and planted it before the first. One pace alone separated the two blades. Each adversary was to stand behind a sabre, extending his arm at full length. In this way each had the muzzle of his opponent’s pistol at six inches from his heart. Whilst Belayef made these preparations Stamm unbuckled his sabre, and divested himself of his coat. His seconds opened his box of pistols, and Zodomirsky, approaching, took without hesitation the nearest to him. Then he placed himself behind one of the sabres.

Stamm regarded him closely; not a muscle of Zodomirsky’s face moved, and there was not about him the least appearance of bravado, but of the calmness of courage.

“He is brave,” murmured Stamm.

And taking the pistol left by Zodomirsky he took up his position behind the other sabre, in front of his adversary.

They were both pale, but whilst the eyes of Zodomirsky burned with implacable resolution, those of Stamm were uneasy and shifting. I felt my heart beat loudly.

Belayef advanced. All eyes were fixed on him.

“Are you ready, gentlemen?” he asked.

“We are waiting, Major,” replied Zodomirsky and Stamm together, and each lifted his pistol before the breast of the other.

A death-like silence reigned. Only the birds sang in the bushes near the place of combat. In the midst of this silence the Major’s voice resounding made everyone tremble.

“One.”

“Two.”

“Three.”

Then we heard the sound of the hammer falling on the cap of Zodomirsky’s pistol. There was a flash, but no sound followed it.

Stamm had not fired, and continued to hold the mouth of his pistol against the breast of his adversary.

“Fire!” said Zodomirsky, in a voice perfectly calm.

“It is not for you to command, Monsieur,” said Stamm, “it is I who must decide whether to fire or not, and that depends on how you answer what I am about to say.”

“Speak, then; but in the name of heaven speak quickly.”

“Never fear, I will not abuse your patience.”

We were all ears.

“I have not come to kill you, Monsieur,” continued Stamm, “I have come with the carelessness of a man to whom life holds nothing, whilst it has kept none of the promises it has made to him. You, Monsieur, are rich, you are beloved, you have a promising future before you: life must be dear to you. But fate has decided against you: it is you who must die and not I. Well, Monsieur Zodomirsky, give me your word not to be so prompt in the future to fight duels, and I will not fire.”

“I have not been prompt to call you out, Monsieur,” replied Zodomirsky in the same calm voice; “you have wounded me by an outrageous comparison, and I have been compelled to challenge you. Fire, then; I have nothing to say to you.”

“My conditions cannot wound your honour,” insisted Stamm. “Be our judge, Major,” he added turning to Belayef. “I will abide by your opinion; perhaps M. Zodomirsky will follow my example.”

“M. Zodomirsky has conducted himself as bravely as possible; if he is not killed, it is not his fault.” Then, turning to the officers round, he said—

“Can M. Zodomirsky accept the imposed condition?”

“He can! he can!” they cried, “and without staining his honour in the slightest.”

Zodomirsky stood motionless.

“The Captain consents,” said old Pravdine, advancing. “Yes, in the future he will be less prompt.”

“It is you who speak, Captain, and not M. Zodomirsky,” said Stamm.

“Will you affirm my words, Monsieur Zodomirsky?” asked Pravdine, almost supplicating in his eagerness.

“I consent,” said Zodomirsky, in a voice scarcely intelligible.

“Hurrah! hurrah!” cried all the officers enchanted with this termination. Two or three threw up their caps.

“I am more charmed than anyone,” said Stamm, “that all has ended as I desired. Now, Captain, I have shown you that before a resolute man the art of shooting is nothing in a duel, and that if the chances are equal a good shot is on the same level as a bad one. I did not wish in any case to kill you. Only I had great desire to see how you would look death in the face. You are a man of courage; accept my compliments. The pistols were not loaded.” Stamm, as he said these words, fired off his pistol. There was no report!

Zodomirsky uttered a cry which resembled the roar of a wounded lion.

“By my father’s soul!” he cried, “this is a new offence, and more insulting than the first. Ah! it is ended, you say? No, Monsieur, it must re-commence, and this time the pistols shall be loaded, if I have to load them myself.”

“No, Captain,” replied Stamm, tranquilly, “I have given you your life, I will not take it back. Insult me if you wish, I will not fight with you.”

“Then it is with me whom you will fight, Monsieur Stamm,” cried Pravdine, pulling off his coat. “You have acted like a scoundrel; you have deceived Zodomirsky and his seconds, and, in five minutes if your dead body is not lying at my feet, there is no such thing as justice.”

Stamm was visibly confused. He had not bargained for this.

“And if the Captain does not kill you, I will!” said Naletoff.

“Or I!” “Or I!” cried with one voice all the officers.

“The devil! I cannot fight with you all,” replied Stamm. “Choose one amongst you, and I will fight with him, though it will not be a duel, but an assassination.”

“Reassure yourself, Monsieur,” replied Major Belayef, “we will do nothing that the most scrupulous honour can complain of. All our officers are insulted, for under their uniform you have conducted yourself like a rascal. You cannot fight with all; it is even probable you will fight with none. Hold yourself in readiness, then. You are to be judged. Gentlemen, will you approach?”

We surrounded the Major, and the fiat went forth without discussion. Everyone was of the same opinion.

Then the Major, who had played the role of president, approached Stamm, and said to him—

“Monsieur, you are lost to all the laws of honour. Your crime was premeditated in cold blood. You have made M. Zodomirsky pass through all the sensations of a man condemned to death, whilst you were perfectly at ease, you who knew that the pistols were not loaded. Finally, you have refused to fight with the man whom you have doubly insulted.”

“Load the pistols! load them!” cried Stamm, exasperated. “I will fight with anyone!”

But the Major shook his head with a smile of contempt.

“No, Monsieur Lieutenant,” he said, “you will fight no more with your comrades. You have stained your uniform. We can no longer serve with you. The officers have charged me to say that, not wishing to make your deficiencies known to the Government, they ask you to give in your resignation on the cause of bad health. The surgeon will sign all necessary certificates. To-day is the 3rd of May: you have from now to the 3rd of June to quit the regiment.”

“I will quit it, certainly; not because it is your desire, but mine,” said Stamm, picking up his sabre and putting on his coat.

Then he leapt upon his horse, and galloped off towards the village, casting a last malediction to us all.

We all pressed round Zodomirsky. He was sad; more than sad, gloomy.

“Why did you force me to consent to this scoundrel’s conditions, gentlemen?” he said. “Without you, I should never have accepted them.”

“My comrades and I,” said the Major, “will take all the responsibility. You have acted nobly, and I must tell you in the name of us all, M. Zodomirsky, that you are a man of honour.” Then, turning to the officers: “Let us go, gentlemen, we must inform the Colonel of what has passed.”

We mounted into the carriages.<ref>Opening quotations were removed, as this is not a quotation.</ref> As we did so we saw Stamm in the distance galloping up the mountain side from the village upon his horse. Zodomirsky’s eyes followed him.

“I know not what presentiment torments me,” he said, “but I wish his pistol had been loaded, and that he had fired.”

He uttered a deep sigh, then shook his head, as if with that he could disperse his gloomy thoughts.

“Home,” he called to the driver.

We took the same route that we had come by, and consequently again passed Mariana Ravensky’s window. Each of us looked up, but Mariana was no longer there.

“Captain,” said Zodomirsky, “will you render me a service?”

“Whatever you wish,” I replied.

“I count upon you to tell my poor Mariana the result of this miserable affair.”

“I will do so. And when?”

“Now. The sooner the better. Stop!” cried Zodomirsky to the coachman. He stopped, and I descended, and the carriage drove on.

Zodomirsky had hardly entered when he saw me appear in the doorway of the saloon. Without doubt my face was pale and wore a look of consternation, for Zodomirsky sprang towards me, crying—

“Great heavens, Captain! What has happened?”

I drew him from the saloon.

“My poor friend, haste, if you wish to see Mariana alive. She was at her window; she saw Stamm gallop past. Stamm being alive, it followed that you were dead. She uttered a cry, and fell. From that moment she has never opened her eyes.”

“Oh, my presentiments!” cried Zodomirsky, “my presentiments!” and he rushed, hatless and without his sabre, into the street.

On the staircase of Mlle. Ravensky’s house he met the doctor, who was coming down.

“Doctor,” he cried, stopping him, “she is better, is she not?”

“Yes,” he answered, “better, because she suffers no more.”

“Dead!” murmured Zodomirsky, growing white, and supporting himself against the wall. “Dead!”

“I have always told her, poor girl! that, having a weak heart, she must avoid all emotion—”

But Zodomirsky had ceased to listen. He sprang up the steps, crossed the hall and the saloon, calling like a madman—

“Mariana! Mariana!”

At the door of the sleeping chamber stood Mariana’s old nurse, who tried to bar his progress. He pushed by her, and entered the room.

Mariana was lying motionless and pale upon her bed. Her face was calm as if she slept. Zodomirsky threw himself upon his knees by the bedside, and seized her hand. It was cold, and in it was clenched a curl of black hair.

“My hair!” cried Zodomirsky, bursting into sobs.

“Yes, yours,” said the old nurse, “your hair that she cut off herself on quitting you at St. Petersburg. I have often told her it would bring misfortune to one of you.”

If anyone desires to learn what became of Zodomirsky, let him inquire for Brother Vassili, at the Monastery of Troitza.

The holy brothers will show the visitor his tomb. They know neither his real name, nor the causes which, at twenty-six, had made him take the robe of a monk. Only they say, vaguely, that it was after a great sorrow, caused by the death of a woman whom he loved.

Word Count: 5058

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Alexandre Dumas. “Zodomirsky’s Duel.” The Strand Magazine, vol. 3, no. 6, 1892, pp. 554-62. Edited by Jacquie Smith. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 21 January 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/zodomirskys-duel/.

Editors

Jacquie Smith

Tyler Vogelsberg

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

23 November 2016

Last modified

20 January 2026

Notes

| ↑1 | Closing quotation mark added to mark the end of her speech. |

|---|