The Haunted House, Part 2: The Ghost in the Clock Room

by Sarah Smith

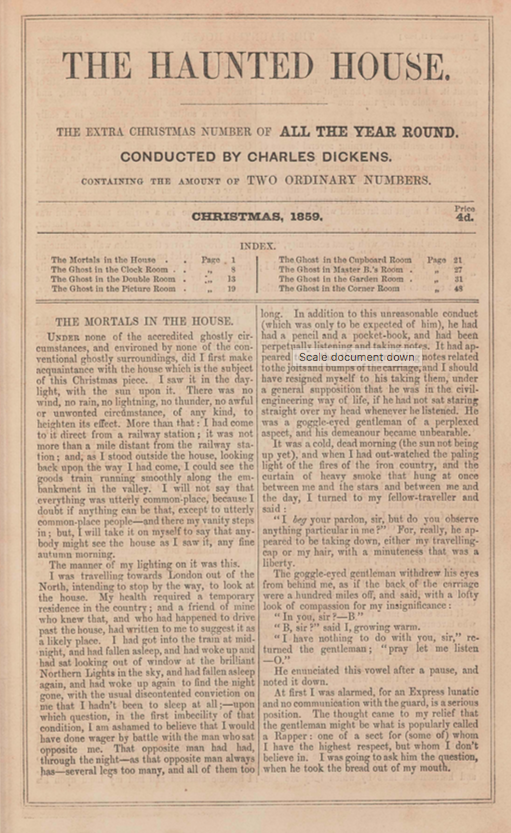

All the Year Round, A Weekly Journal, vol. 2, Christmas issue (1859)

Pages 8-13

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Haunted House” is a portmanteau story written by Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Sarah Smith, George Augustus Sala, Adelaide Proctor, and Elizabeth Gaskell. It was published as a Christmas special in Dickens’s periodical All the Year Round. The story begins when the narrator decides to rent a house which is rumored to be haunted. After strange noises and unexplained disruptions frighten off his servants, the narrator decides to dismiss his staff and invite some friends to spend the holidays with him while they attempt to discover the true nature of the house’s haunting.

This portion of the story is told by a ghost who haunts the Clock Room and details her love life. As a young woman she was extremely flirtatious and didn’t take love seriously, but her life took a turn when she tried her wiles on the rich recluse of her town. This story provides an interesting portrayal of Victorian romance, as well as Victorian ideas about what was and was not honorable behavior in courtship.

Advisory: This story contains an ableist slur.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the second of eight parts:

- The Haunted House, Part 1: The Mortals in the House (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 2: The Ghost in the Clock Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 3: The Ghost in the Double Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 4: The Ghost in the Picture Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 5: The Ghost in the Cupboard Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 6: The Ghost in Master B.’s Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 7: The Ghost in the Garden Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 8: The Ghost in the Corner Room (1859)

MY cousin, John Herschel, turned rather red, and turned rather white, and said he could not deny that his room had been haunted. The Spirit of a woman had pervaded it. On being asked by several voices whether the Spirit had taken any terrible or ugly shape, my cousin drew his wife’s arm through his own, and said decidedly, “No.” To the question, had his wife been aware of the Spirit? he answered, “Yes.” Had it spoken? “Oh dear, yes!” As to the question, “What did it say?” he replied apologetically, that he could have wished his wife would have undertaken the answer, for she would have executed it much better than he. However, she had made him promise to be the mouthpiece of the Spirit, and was very anxious that he should withhold nothing; so, he would do his best, subject to her correction. “Suppose the Spirit,” added my cousin, as he finally prepared himself for beginning, “to be my wife here, sitting among us:”

I was an orphan from my infancy, with six elder half-sisters. A long and persistent course of training imposed upon me the yoke of a second and diverse nature, and I grew up as much the child of my eldest sister, Barbara, as I was the daughter of my deceased parents.

Barbara, in all her private plans, as in all her domestic decrees, inexorably decided that her sisters must be married; and, so powerful had been her single but inflexible will, that each of them had been advantageously settled, excepting myself, upon whom she built her highest hopes.

Most people know a character such as I had grown—a mindless, flirting girl, whose acknowledged vocation was the hunting and catching of an eligible match; rather pretty, lively, and just sentimental enough to make me a very pleasant companion for an idle hour or two, as I exacted and enjoyed the slight attentions an unemployed man is pleased to offer. There was scarcely a young man in the neighbourhood with whom I had not coquetted. I had served my seven years’ apprenticeship to my profession, and had passed my twenty-fifth birthday without having achieved my purpose, when Barbara’s patience was wearied, and she spoke to me with a decision and explicitness we had always avoided; for, on some subjects, it is better to have a silent understanding than an expressed opinion.

“Stella,” she said, solemnly, “you are now five-and-twenty, and every one of your sisters were in homes of their own before they were your age; yet none of them had your advantages or your talents. But I must tell you frankly your chances are on the wane, and, unless you exert yourself, our plans must fail. I have observed an error into which you have fallen, and which I have not mentioned before. Besides your very open and indiscriminate flirtations—which young men regard only as an amusing pastime—you have a way with you of rallying and laughing at any one who begins to look really serious. Now your opportunity rests upon the moment when they begin to be earnest in their manner. Then you should seem confused and silenced; you ought to lose your vivacity, and half avoid them; seeming almost frightened and quite bewildered by the change. A little melancholy goes a deal further than the utmost cheerfulness; for, if a man believes you can live without him, he will not give you a second thought. I could name half a dozen most eligible settlements you have lost by laughing at the wrong minute. Mortify a man’s self-love, Stella, and you can never heal the wound.”

I paused for a minute or two before I answered; for the original suppressed nature that I had inherited from my unknown mother, was stirring unwonted feeling in my heart.

“Barbara,” I answered, with timidity, “among all the people I have known, I never saw one whom I could reverence and look up to; nor, I am half ashamed to use the word, whom I could love.”

“I do not wonder you are ashamed,” said Barbara, severely. “At your age, you cannot expect to fall in love like a girl of seventeen. But I tell you, definitely and distinctly, it is necessary that you should marry; and we had better work in concert now. So, if you will decide upon any one, I will give you every assistance in my power, and, if you will only concentrate your wishes and abilities, you cannot fail. Propinquity is all you require, if you once make up your mind.”

“I do not like any one I know,” I replied, moodily; “and I have no chance with those who have known me; so I decide upon besieging Martin Fraser.”

Barbara received this announcement with a snort of derisive anger.

The neighbourhood in which we lived was a populous iron district, where, though there were few families of ancient birth or high standing, there were many of our own station, forming a pleasant, hospitable, social class. Our residences were commodious modern houses, built at convenient distances from each other. Some of these, including our own, were the property of an infirm old man, who dwelt in his family mansion, the last of the many gabled, half-timbered, Elizabethan houses which had stood upon the undiscovered iron and coal fields. The last relics of the rural aristocracy of the district, Mr. Fraser and his son led a strictly recluse life, avoiding all communication with their neighbours, whose gaiety and hospitality they could not reciprocate. No one intruded upon their privacy, excepting for the most necessary business transactions. The elder man was almost bedridden, and the younger was said to be entirely absorbed in scientific pursuits. No wonder that Barbara laughed; but her ridicule only excited and confirmed my determination; and the very difficulty of the enterprise gave it the interest that all my other efforts had lacked. I argued obstinately with Barbara till I won her consent.

“You must write to old Mr. Fraser,” I said. “Do not mention the young one, and say your youngest sister is studying astronomy, and, as he possesses the only telescope in the country, you will be greatly indebted to him if he would let her see it.”

“There is one thing in your favour,” Barbara remarked, as she sat down to write; “the old gentleman was once engaged to your mother.”

Oh! I am humbled to think how shrewdly we managed our business, and extorted a kind invitation from Mr. Fraser to the “daughter of his old friend, Maria Horley.”

It was an evening in February when, accompanied only by an old servant—for Barbara was not included in the invitation—I first crossed the threshold of Martin Fraser’s home.

An air of profound peace pervaded the dwelling. I entered it with a vague, uneasy consciousness of unfitness and treachery. My attendant remained in the entrance-hall, and, as I was conducted to the library, a feeling of shyness stole over me, which was prompting me to retreat; but, with the recollection that I was becomingly dressed, I regained my confidence, and advanced smilingly into the room. It was a low, oaken-panelled room, sombre, with massive antique furniture that threw deep and curious shadows around, in the flickering light of a fire, by which stood, instead of the recluse, Martin Fraser whom I expected to meet, a quaint, little child, dressed in the garb of a woman, and with a woman’s self-possession and ease of manner.

“I am very glad to see you. You are welcome,” she said, advancing to meet me, and extending her hand to lead me to a seat. She clasped my hand with a firm and peculiar grasp; a clasp of guidance and assistance, quite unlike the ordinary timidity or inertness of a child’s manner, and, placing me in a chair before the fire, she seated herself nearly opposite me.

I made a few embarrassed remarks, to which she replied, and then I noticed her furtively and in silence. A huge black retriever lay motionless at her feet, which rested upon him, covered with the folds of the long robe-like dress she wore. There was an expression of placidity, slightly pensive, upon her tiny features, heightened by a peculiar habit of closing the eyes, which is rarely seen in children, and always gives them a statuesque appearance. It seemed as though she had withdrawn herself into a solitary self-communing, of which there could be no expression either by words or looks. I grew afraid of the silent, weird-like creature, sitting without apparent breath or motion in the dancing fire-light, and I was glad when the door opened, and the object of my pursuit entered. I looked at him inquisitively, for I had recovered from my sense of treachery, and it amused me to think how unconscious he was of our definite plans concerning him. Hitherto the young men I had met had a fear of being caught, greater than my desire to catch them, so our contest had been an open and equal one; but Martin Fraser knew nothing of the wiles of woman. I remembered that my brown hair fell in curls round my face, and that my dark blue eyes were considered expressive, when I looked up to meet his gaze; but when he accosted me with an air of grave preoccupation and of courteous indifference that would not permit him to notice my personal charms, I trembled to think that all I knew of astronomy was what I had learned at school in Mangnall’s Questions.

The grave, austere man said at once:

“My father, Mr. Fraser, is altogether confined to his own rooms, but he desires the favour of a visit from you. Upon me devolves the honour of showing you what you require to view through the telescope, and, while I adjust it, will you oblige him by conversing with him for a few minutes? Lucy Fraser will accompany you.”

The child rose, and, taking my hand again in her firm hold, led me to the old man’s sitting-room.

“You are like your mother, child,” he said, after looking at me long; “you have her face and eyes; not a whit like your sister Barbara. How did you come by your out-of-the-way name, Stella?”

“My father named me after a favourite racer,” I answered, for the first time giving the simple derivation of my name.

“Just like him,” laughed the old man; “I remember the horse well. I knew your father as well as I do my son Martin. You have seen my son, young lady? Yes, I thought so; and this is my granddaughter, Lucy Fraser, the last chip of the old block; for my son is not a marrying man, and we have adopted her as our heir, and she is always to keep her name, and be the founder of another line of Frasers.”1Original omits closing quotation mark.

The child stood with pensive, downcast eyes, as though already bowed down by her weight of cares and responsibilities; the old man chatted on, till the deep tones of an organ resounded through the house.

“My uncle is ready for us,” she said to me.

We paused at the library door, for I laid my hand restrainingly on Lucy Fraser’s shoulder, and stood listening to the wonderful music the organ poured forth. It was such as I had never heard before; roaring and swelling like the ceaseless surging of the sea; and, here and there, a single wailing note which seemed to pierce me with an inexpressible pain. When it had ended, I stood before Martin Fraser silent and subdued.

The telescope had been carried out to the end of the terrace, where the house could not intercept our view; and thither Lucy Fraser and I followed the astronomer. We stood upon the highest point of an imperceptibly rising table-land, the horizon of which was from twenty to forty miles distant. An infinite dome of sky was expanded above us, an ocean of firmament of which the dwellers among houses and mountains can have but little conception. The troops of glittering stars, the dark, shrouding night, the unaccustomed voices of my companions, deepened the awe that oppressed me, and, as I stood between them, I became as earnest and occupied as themselves. I forgot everything but the incomprehensible grandeur of the universe revealed to me, and the majestic sweep of the planets across the field of the telescope. What a freshness of awe and delight came over me! What floods of thought came, wave upon wave, across my mind! And how insignificant I felt before this wilderness of worlds!

I asked, with the humility of a child—for all affectation had been charmed away—if I might come again soon?

Martin Fraser met my uplifted eyes with a keen and penetrating look. I did not quail under it, for I was thinking only of the stars. As he looked, his mouth relaxed into a pleased and genial smile.

“We shall always be glad to see you,” he replied.

Barbara was sitting up for me when I returned, and was about to address me with some worldly speculative remark, when I interrupted her quickly. “Not one word, Barbara, not one question, or I never go near The Holmes again.”

I cannot dwell upon details. I went often to the house. Into the dull routine of Mr. Fraser’s and Lucy’s life, I came (I suppose) like a streak of sunshine, lighting up the cloud that had been creeping over them. To both, I brought wholesome excitement and merriment, and so I became dear and necessary to them. But over myself, there came a great and an almost incredible change. I had been frivolous, self-seeking, soulless; but the solemn study I had begun with other studies that came in its train, awoke me from my inanity, to a life of mental activity. I absolutely forgot my purpose; for I had at once perceived that Martin Fraser was as distant and as self-poised as the Polar Star. So I became to him merely a diligent and insatiable pupil, and he was to me only a grave and exacting master, to be propitiated by my most profound reverence. Each time I crossed the threshold of his quiet home, all the worldliness and coquetry of my nature fell from my soul like an unfit garment, and I entered as into a temple, simple, real, and worshipping.

The happy summer passed away, the autumn crept on, and for eight months I had visited the Frasers constantly, and had never, by word, or look, or tone, intentionally deceived them.

Lucy Fraser and I had long looked forward to an eclipse of the moon, which was visible early in October. I left my home alone in the twilight of that evening, my thoughts dwelling upon the coming pleasure, when, just as I drew near The Holmes, there overtook me one of the young men with whom I had flirted in former times.

“Good evening, Stella,” he exclaimed familiarly, “I have not seen you for a long time. Ah! you are pursuing other game I suppose; but are you not aiming rather too high this time? Well, you are in luck just now, for if Martin Fraser does not come forward, there is George Yorke, just come home from Australia with an immense fortune, and he is longing to remind you of some tender passages between you before he went out. He was showing us a lock of your hair after dinner at the Crown yesterday.”

I listened to this speech with no outward demonstration; but the reality and mortification of my degradation was gnawing me; and, hastening onward to my sanctuary, I sought the presence of my little Lucy Fraser.

“I have done wrong to-day,” she said. “I have been deceitful. I think I ought to tell you, that you may not think too well of me; but I want you to love me as much as ever. I have not told a story, but I have acted one.”

Lucy Fraser leaned her tiny brow upon her tiny fingers, and her eyes closed in silent self-reading.

“My uncle says,” she continued, looking up for a moment, and blushing like a woman, “that women are, perhaps, less truthful than men. Because they cannot do things by strength, they do them by cunning. They live falsely. They deceive their own selves. Sometimes women deceive for amusement. He has taught me some words which I shall understand better some day:

To thine own self be true,

And it will follow as the night to day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

I stood before the child abashed and speechless, listening with burning cheeks.

“Grandpapa showed me a verse in the Bible which is awful to me. Listen. ‘I find more bitter than death, the woman whose heart is snares and nets, and her hands as bands: whoso pleaseth God shall escape from her, but the sinner shall be taken by her.”

I hid my face in my hands though no eye was on me; for Lucy Fraser had veiled hers with their tremulous lids; and, as I stood confounded and self-accused, a hand was laid upon my arm, and Martin Fraser’s voice said,

“The eclipse, Stella!”

I started at this first utterance of my name, which he had never spoken before. I was completely unnerved, when I found that Lucy Fraser was not to accompany us on the terrace. As Martin Fraser stooped to see if the telescope were rightly adjusted for my use, I shrank from him.

“What is the meaning of this, Stella?” he exclaimed, as I burst into tears. “Shall I speak to you now, Stella?” he said, “while there is yet time, before you leave us. Does your heart cling to us as our hearts cling to you, till we dare not think of the void there will be in our home when you are gone? We did not live before we knew you. You are our health and our life. I have noted you as I never watched a woman before, and I find no fault in you, my pearl, my jewel, my star. Hitherto, woman and deceit have been inseparably conjoined in my mind; but your innocent heart is the home of truth. I know you have had no thought of this, and my vehemence alarms you; but tell me plainly if you can love me?”

He had taken me in his arms, and my head rested against his strongly throbbing heart. His sternness and austerity were gone, and he offered me the undiminished wealth of a love that had not been wasted in fickle likings. My success was perfect, and how gladly would I have remained there till my silence had grown eloquent! But Barbara rose to my memory, and Lucy Fraser’s words still tingled in my ears. The black shadow eating away the heart of the moon seemed to pause in its measured motion. All heaven looked down upon us through the solemn stars. The rustling leaves were hushed, and the scented autumn breeze ceased for a minute; a cloud of truth-compelling witnesses echoed the cry of my awakened conscience. I withdrew myself, sad and shame-stricken.

“Martin Fraser,” I said, “your words constrain me to be true. I am the falsest woman you ever met. I came here with the sole and definite intention of attracting you; and if you had ever gone out into our circle, you would have heard of me only as a flirt, a heartless coquette. I dare not bring falsehood to your fireside, and the bitterness of death to your heart. Do not speak to me now; have patience, and I will write to you!”

He would have detained me, but I sprang away, and, running swiftly down the avenue, I passed out of my Eden, with the sentence of perpetual banishment in my heart. The eclipse was at the full, and a horror of darkness and dismay engulfed me, as I stood shivering and sobbing under the restless poplars.

Barbara met me as I hastened to hide myself in my own room, and, with her cold glittering eyes fixed inquiringly on me, said,

“Well, what is the matter with you?”

“Nothing,” I answered, “only I am tired of astronomy, and I shall not go to The Holmes again. It is of no use.”

“I always said so,” she replied. “However, to bring matters to a crisis, I gave Mr. Fraser notice we should leave at Christmas. Then you are satisfied that it would be a waste of time to continue going there?”

“Quite,” I said, and passed on to my room, to learn, through the weary hours of that night, what desolation and hopelessness meant.

The next day I wrote to Martin Fraser, in every word sacred truth, excepting that, self-deceived, and with a false pride even in my utter humiliation, I told him I had not loved, and did not love him.

The first object upon which my eyes rested every joyless morning, were the tall poplar trees, waving round his house, and beckoning maddeningly to me. The last thing I saw at night was the steady light in his library, shining like a star among the laurels. But, him I could never see; for my letter had been too explicit to suggest a hope; and I could not, for shame, attempt to meet him in his walks. All that remained, for me was to return to my former life, if I could by any means feed my hungering and fainting soul with the husks that had once satisfied me.

George Yorke renewed his addresses to me, offering me wealth beyond our expectations. It was a sore temptation; for before me lay a monotonous and fretted life with Barbara, and a solitary, uncared for old age. Why could not I live as thousands of other women, who were not unhappy wives? But I remembered a passage I had read in one of Martin’s books: “It is not always our duty to marry; but it is always our duty to abide by right; not to purchase happiness by loss of honour; not to avoid unweddedness by untruthfulness;” and, setting my face steadily to meet the bleakness and bareness of my lot, I rejected the proposal.

Barbara was terribly exasperated; and very miserable we both were, until she accepted an invitation to spend the Christmas with one of her sisters, while I was left, with my old nurse, to superintend the moving of the furniture. I wished to linger in our old home till the last moment; and I was glad to be alone on Christmas-day in the deserted house, that, in solitude, I might make my mental record of all its associations and remembrances, before the place knew me no more. So, on Christmas-eve, I wandered through the empty rooms, not more empty than my heart, which was being dismantled of its old memories and newer but deeper tendernesses, until I paused mechanically before the window, whence I had often looked across to The Holmes.

The air had been dense and murky all day, with thickly falling snow; but the storm was over, and the moonless sky bright with stars: while the glistening snow reflected light enough to show me where stood, like a dark mass against the sky, the house of Martin Fraser. His room was dark, as it had been for many nights before; but old Mr. Fraser’s window, which was nearer to our house, emitted a brilliant light across the white lawn. I was exhausted with over-work and over-excitement, and leaning there, pressing my heated cheeks against the frosty panes, I rehearsed to myself all the incidents of my intercourse with them; and there followed through my mind picture after picture, dream within dream, visions of the happiness that might have been mine.

As I stood thus, with tears stealing through the clasped hands that covered my eyes, my nurse came in to close the shutters. She started nervously when she saw me.

“I thought you were your mother,” she exclaimed. “I have seen her stand just so, hundreds of times.”

“Susan, how was it that my mother did not marry Mr. Fraser?”

“They were like other people—didn’t understand one another, much as they were in love,” she answered. “Mr. Fraser’s first marriage had been for money, and was not a happy one, so he had grown something stern. They quarrelled, and your mother was provoked to marry Mr. Gretton, your father. Well! Mr. Fraser became an old man all at once, and scarcely ever left his own house; so that she never saw him again, near as he lived: though I have often seen her, when your father was off to balls or races or public meetings, standing here just as you stood now. Only the last time you were in her arms, she was leaning against this window when I brought you in to say good night, and she whispered softly, looking up to Heaven, “I have tried to do my duty to my husband and to my little child!”

“Nurse,” I said, “leave me; do not shut the window yet.” It was no longer a selfish emotion that possessed me. I had been murmuring that there was no sorrow like my sorrow; but my mother’s error had been graver, and her trials deeper than mine. The burden she had borne had weighed her down into an early grave; but it had not passed away from earth with her. It rested now, heavily augmented by her death, upon the heart of the aged man, who, doubtless, in the contemplative time, was reviewing the events of his past life, and this, chiefly, because it was the saddest of them all. I longed to see him once again—to see him who had mourned my mother’s death more bitterly and lastingly than any other being, and I determined to steal secretly across the fields, and up the avenue, and, if his window were uncurtained as its brightness suggested, to look upon him once more in remembrance of my mother.

I hesitated upon our door-step, as though my mother and myself were both concerned in some doubtful enterprise; but, with the hardihood of my nature, I drove away the scruple, and passed on into the frosty night.

Yes, the window was uncurtained. I could tell that at the avenue gate; and I should see him, whom my mother loved, lying alone and uncheered upon his couch, as he would lie now all his weary years through, till Lucy Fraser was old enough to be a daughter to him. And then I remembered a rumour that the old man’s grandchild was dying, which Susan had told me sorrowfully an hour or two ago; and, growing bewildered, I ran on swiftly until I stood before the window.

It was no longer an invalid’s room; the couch was gone and the sheltering screen, and Lucy’s little chair within it. Neither were there any appliances of modern luxury or wealth; no softness, nor colouring, nor gorgeousness: it was simply the library and workroom of a busy student, who was forgetful and negligent of comfort. Yet, such as it was, my heart recognised it as home. There Martin sat, deep, as was his wont, in complicated calculations, and frequent reference to the books that were strewn about.

Could it be possible that yonder absorbed man had once spoken passionately to me of love, and now he sat in light, and warmth, and indifference, almost within reach of my hand, while I, like an outcast, stood in cold, and darkness, and despair? Was there, then, no echo of my footstep lingering about the threshold, and no shadowy memory of my face coming between him and his studies? I had forfeited the right to sit beside him, reading the observations his pencil noted down, and chasing away the gloom that was deepening on his nature; and I had not the hope, which would have been really a hope and a consolation to me, that some other woman, more true and more worthy, would by-and-by own my forfeited right.

I heard a bell tinkle, and Martin rose and left the room. I wondered if I should have time to creep in, and steal but one scrap of paper which had been thrown aside carelessly; but, as I tremblingly held the handle of the glass door, he returned, bearing in his arms the emaciated form of little Lucy Fraser. He had wrapped her carefully in a large cloak, and now, as he wheeled a chair to the fire and placed her in it, every rigid lineament of his countenance was softened into tenderness. I stretched out my arms towards him with an intense yearning to be gathered again to his noble heart, and have this chill and darkness dissipated; I turned away, with this last tender image of him graven on my memory, to retrace my steps to my desolate home.

There was a sudden twittering in the ivy overhead, and a little bird, pushed out of its nest into the cold night air, came fluttering down, and flew against the lighted panes. In an instant, his dog, which had been uneasy at my vicinity before, stood baying at the window, and I had only time to escape and hide myself among the shrubs, when he opened it, and stepped out upon the terrace. The dog tracked down the path by which I had come, barking joyfully as he careered along the open fields; and, as Martin looked round, I cowered more closely into the deepest shadows. I knew he must find me; for my footmarks were plain upon the newly-fallen snow, and an extravagant sensation of shame and gladness overpowered me. I saw him lose the footprints once or twice, but at last he was upon the right trace, and, lifting the boughs beneath which I had hidden, he found me among the laurels. I was crouching, and he stooped down curiously.

“It is Stella,” I said, faintly.

“Stella?” he echoed.

He lifted me from the ground like a truant child, whom he had expected home every hour, carried me across the terrace into the library, and set me down in the light and warmth of his own hearth. One little kiss to the child, whose eyes beamed with a strange light upon us; and then, taking both my hands in his, he bent down and read my face. I met his gaze unshrinkingly, eye to eye. We sounded the depths of each other’s heart in that long, unwavering look. Never more could there be doubt or mistrust; never again deception or misconstruction, between us.

Our star had arisen, and full orbed, rounded into perfection, shed a soft and brilliant light upon the years to come. Chime after chime, like the marriage peal of our souls, came the sound of distant bells across the snow, and roused us from our reverie.

“I thought I had lost you altogether,” said Martin to me. “I believed you would come back to me, somehow, at some time; but this evening I heard that you were gone, and I was telling Lucy Fraser so, not long since. She has been pining to see you.”

Now, he suffered me to take the child upon my lap, and she nestled closely to me, with a weary sigh, resting her head upon my bosom. Just then, we heard the carol singers coming up the avenue, and Martin drew the curtains over the window, before which they stationed themselves to sing the legend of the miraculous star in the East.

When the singers ended and raised their cry of “We wish you a merry Christmas, and a happy New Year!” he went out into the porch to speak to them, and I hid my face in the child’s curls, and thanked God who had so changed me.

“But what is this, Martin?” I cried in terror, as I raised my head, on his return.

The child’s downcast eyes were closely sealed, and her little firm hand had grown lax and nerveless. Insensible and breathless, she lay in my arms like a withering flower.

“It is only fainting,” said Martin; “she has been drooping ever since you left us, Stella; and my only hope for her recovery rests in your ministering care.”

All that night, I sat with the little child resting on my bosom; revived from her death-like swoon, and sleeping calmly in my arms because she was already beginning to share in the life and joy and brightness of my heart. There was perfect silence and tranquility enclosing us in a blissful oasis, interrupted only once by the entrance of my nurse, who had been found by Martin in a state of the utmost perplexity and alarm.

The happy Christmas morning dawned. I asked my nurse to arrange my hair in the style in which my mother used to wear hers. And when, after a long conversation with Susan, Mr. Fraser received me as his daughter with great emotion and affection, and oftener called me Maria than Stella, I was satisfied to be identified with my mother. Then, in the evening, sitting amongst them, a passion of trembling and weeping seized me, which could only be soothed by the fondest assurances. After which I sang them some old songs, with nothing in them but their simple melody; and Mr. Fraser talked freely of former years and of the times to come; and Lucy’s eyes almost laughed.

Then Martin took me home along the familiar path, which I had so often traversed alone and fearless; but the excess of gladness made me timid, and at every unusual sound I crept closer to him, with a sweet sense of being protected.

One sunny day in spring, with blithe Lucy and triumphant dictatress Barbara for my bridesmaids, I accepted, humbly and joyfully, the blessed lot of being Martin Fraser’s wife. And even in the scenes of the empty-headed folly of my girlhood, I thenceforth tried to be better, and to do my duty in love, gratitude, and devotion. Only, at first, Martin pretended not to believe that on that night I stole out to have a last glimpse, not of him, but of his father: I knowing nothing of the change that had transformed Mr. Fraser’s sitting-room into his own study.

Word Count: 5957

This story is continued in The Haunted House, Part 3: The Ghost in the Double Room.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Danny Daw

Posted

26 March 2021

Last modified

11 January 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | Original omits closing quotation mark. |

|---|

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.