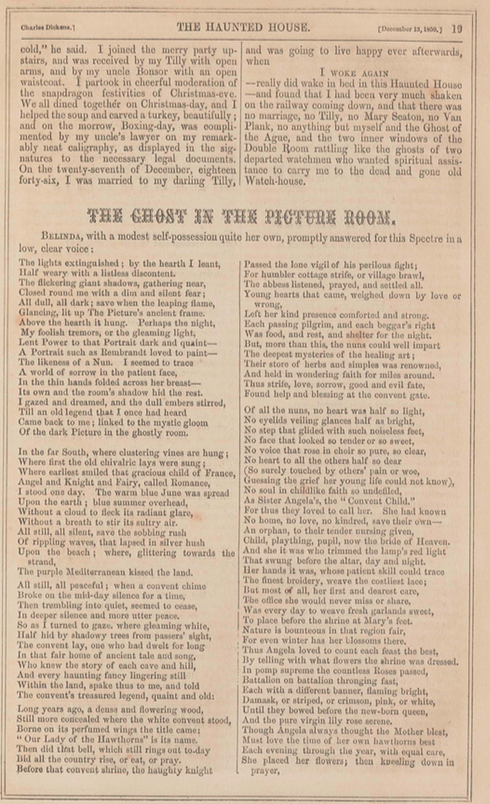

The Haunted House, Part 4: The Ghost in the Picture Room

All the Year Round, A Weekly Journal, vol. 2, Christmas issue (1859)

Pages 19-21

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Haunted House” is a portmanteau story written by Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Sarah Smith, George Augustus Sala, Adelaide Proctor, and Elizabeth Gaskell. It was published as a Christmas special in Dickens’s periodical All the Year Round. The story begins when the narrator decides to rent a house which is rumored to be haunted. After strange noises and unexplained disruptions frighten off his servants, the narrator decides to dismiss his staff and invite some friends to spend the holidays with him while they attempt to discover the true nature of the house’s haunting.

This story was written in verse by the poet, Adelaide Proctor. It relates the legend of a young nun, once the pride of her convent, who falls from grace and later receives forgiveness through a miracle.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the fourth of eight parts:

- The Haunted House, Part 1: The Mortals in the House (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 2: The Ghost in the Clock Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 3: The Ghost in the Double Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 4: The Ghost in the Picture Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 5: The Ghost in the Cupboard Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 6: The Ghost in Master B.’s Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 7: The Ghost in the Garden Room (1859)

- The Haunted House, Part 8: The Ghost in the Corner Room (1859)

BELINDA, with a modest self-possession quite her own, promptly answered for this Spectre in a low, clear voice:

The lights extinguished; by the hearth I leant,

Half weary with a listless discontent.

The flickering giant shadows, gathering near,

Closed round me with a dim and silent fear;

All dull, all dark; save when the leaping flame,

Glancing, lit up The Picture’s ancient frame.

Above the hearth it hung. Perhaps the night,

My foolish tremors, or the gleaming light,

Lent Power to that Portrait dark and quaint—

A Portrait such as Rembrandt loved to paint—

The likeness of a Nun. I seemed to trace

A world of sorrow in the patient face,

In the thin hands folded across her breast—

Its own and the room’s shadow hid the rest.

I gazed and dreamed, and the dull embers stirred,

Till an old legend that I once had heard

Came back to me; linked to the mystic gloom

Of the dark Picture in the ghostly room.

In the far South, where clustering vines are hung;

Where first the old chivalric lays were sung;

Where earliest smiled that gracious child of France,

Angel and Knight and Fairy, called Romance,

I stood one day. The warm blue June was spread

Upon the earth; blue summer overhead,

Without a cloud to fleck its radiant glare,

Without a breath to stir its sultry air.

All still, all silent, save the sobbing rush

Of rippling waves, that lapsed in silver hush

Upon the beach; where, glittering towards the strand,

The purple Mediterranean kissed the land.

All still, all peaceful; when a convent chime

Broke on the mid-day silence for a time,

Then trembling into quiet, seemed to cease,

In deeper silence and more utter peace.

So as I turned to gaze, where gleaming white,

Half hid by shadowy trees from passers’ sight,

The convent lay, one who had dwelt for long

In that fair home of ancient tale and song,

Who knew the story of each cave and hill,

And every haunting fancy lingering still

Within the land, spake thus to me, and told

The convent’s treasured legend, quaint and old:

Long years ago, a dense and flowering wood,

Still more concealed where the white convent stood,

Borne on its perfumed wings the title came:

“Our Lady of the Hawthorns” is its name.

Then did that bell, which still rings out to-day

Bid all the country rise, or eat, or pray.

Before that convent shrine, the haughty knight

Passed the lone vigil of his perilous fight;

For humbler cottage strife, or village brawl,

The abbess listened, prayed, and settled all.

Young hearts that came, weighed down by love or wrong,

Left her kind presence comforted and strong.

Each passing pilgrim, and each beggar’s right

Was food, and rest, and shelter for the night.

But, more than this, the nuns could well impart

The deepest mysteries of the healing art;

Their store of herbs and simples was renowned,

And held in wondering faith for miles around.

Thus strife, love, sorrow, good and evil fate,

Found help and blessing at the convent gate.

Of all the nuns, no heart was half so light,

No eyelids veiling glances half as bright,

No step that glided with such noiseless feet,

No face that looked so tender or so sweet,

No voice that rose in choir so pure, so clear,

No heart to all the others half so dear

(So surely touched by others’ pain or woe,

Guessing the grief her young life could not know),

No soul in childlike faith so undefiled,

As Sister Angela’s, the “Convent Child.”

For thus they loved to call her. She had known

No home, no love, no kindred, save their own—

An orphan, to their tender nursing given,

Child, plaything, pupil, now the bride of Heaven.

And she it was who trimmed the lamp’s red light

That swung before the altar, day and night.

Her hands it was, whose patient skill could trace

The finest broidery, weave the costliest lace;

But most of all, her first and dearest care,

The office she would never miss or share,

Was every day to weave fresh garlands sweet,

To place before the shrine at Mary’s feet.

Nature is bounteous in that region fair,

For even winter has her blossoms there.

Thus Angela loved to count each feast the best,

By telling with what flowers the shrine was dressed.

In pomp supreme the countless Roses passed,

Battalion on battalion thronging fast,

Each with a different banner, flaming bright,

Damask, or striped, or crimson, pink, or white,

Until they bowed before the new-born queen,

And the pure virgin lily rose serene.

Though Angela always thought the Mother blest,

Must love the time of her own hawthorns best

Each evening through the year, with equal care,

She placed her flowers; then kneeling down in prayer,

As their faint perfume rose before the shrine,

So rose her thoughts, as pure and as divine.

She knelt until the shades grew dim without,

Till one by one the altar lights shone out,

Till one by one the nuns, like shadows dim,

Gathered around to chant their vesper hymn;

Her voice then led the music’s winged flight,

And “Ave, Maris Stella” filled the night.

But wherefore linger on those days of peace?

When storms draw near, then quiet hours must cease.

War, cruel war, defaced the land, and came

So near the convent with its breath of flame,

That, seeking shelter, frightened peasants fled,

Sobbing out tales of coming fear and dread.

Till after a fierce skirmish, down the road,

One night came straggling soldiers, with their load

Of wounded, dying comrades; and the band,

Half pleading, yet as if they could command,

Summoned the trembling sisters, craved their care,

Then rode away, and left the wounded there.

But soon compassion bade all fear depart,

And bidding every sister do her part,

Some prepare simples, healing salves, or bands,

The abbess chose the more experienced hands,

To dress the wounds needing most skilful care;

Yet even the youngest novice took her share,

And thus to Angela, whose ready will

And pity could not cover lack of skill,

The charge of a young wounded knight must fall,

A case which seemed least dangerous of them all.

Day after day she watched beside his bed,

And first in utter quiet the hours fled:

His feverish moans alone the silence stirred,

Or her soft voice, uttering some pious word.

At last the fever left him; day by day

The hours, no longer silent, passed away.

What could she speak of? First, to still his plaints,

She told him legends of the martyr’d saints;

Described the pangs, which, through God’s plenteous grace,

Had gained their souls so high and bright a place.

This pious artifice soon found success—

Or so she fancied—for he murmured less.

And so she told the pomp and grand array

In which the chapel shone on Easter Day,

Described the vestments, gold, and colours bright,

Counted how many tapers gave their light;

Then, in minute detail went on to say,

How the high altar looked on Christmas-day:

The kings and shepherds, all in green and white,

And a large star of jewels gleaming bright.

Then told the sign by which they all had seen,

How even nature loved to greet her Queen,

For, when Our Lady’s last procession went

Down the long garden, every head was bent,

And rosary in hand each sister prayed;

As the long floating banners were displayed,

They struck the hawthorn boughs, and showers and showers

Of buds and blossoms strewed her way with flowers.

The knight unwearied listened; till at last,

He too described the glories of his past;

Tourney, and joust, and pageant bright and fair,

And all the lovely ladies who were there.

But half incredulous she heard. Could this—

This be the world? this place of love and bliss!

Where, then, was hid the strange and hideous charm,

That never failed to bring the gazer harm?

She crossed herself, yet asked, and listened still,

And still the knight described with all his skill,

The glorious world of joy, all joys above,

Transfigured in the golden mist of love.

Spread, spread your wings, ye angel guardians bright,

And shield these dazzling phantoms from her sight!

But no; days passed, matins and vespers rang,

And still the quiet nuns toiled, prayed, and sang,

And never guessed the fatal, coiling net

That every day drew near, and nearer yet,

Around their darling; for she went and came

About her duties, outwardly the same.

The same? ah, no! even when she knelt to pray,

Some charméd dream kept all her heart away.

So days went on, until the convent gate

Opened one night. Who durst go forth so late?

Across the moonlit grass, with stealthy tread,

Two silent, shrouded figures passed and fled.

And all was silent, save the moaning seas,

That sobbed and pleaded, and a wailing breeze

That sighed among the perfumed hawthorn trees.

What need to tell that dream so bright and brief,

Of joy unchequered by a dread of grief?

What need to tell how all such dreams must fade,

Before the slow foreboding, dreaded shade,

That floated nearer, until pomp and pride,

Pleasure and wealth, were summoned to her side,

To bid, at least, the noisy hours forget,

And clamour down the whispers of regret.

Still Angela strove to dream, and strove in vain;

Awakened once, she could not sleep again.

She saw, each day and hour, more worthless grown

The heart for which she cast away her own;

And her soul learnt, through bitterest inward strife,

The slight, frail love for which she wrecked her life;

The phantom for which all her hope was given,

The cold bleak earth for which she bartered heaven!

But all in vain; what chance remained? what heart

Would stoop to take so poor an outcast’s part?

Years fled, and she grew reckless more and more,

Until the humblest peasant closed his door,

And where she passed, fair dames, in scorn and pride,

Shuddered, and drew their rustling robes aside.

At last a yearning seemed to fill her soul,

A longing that was stronger than control:

Once more, just once again, to see the place

That knew her young and innocent; to retrace

The long and weary southern path; to gaze

Upon the haven of her childish days;

Once more beneath the convent roof to lie;

Once more to look upon her home—and die!

Weary and worn—her comrades, chill remorse

And black despair, yet a strange silent force

Within her heart, that drew her more and more—

Onward she crawled, and begged from door to door.

Weighed down with weary days, her failing strength

Grew less each hour, till one day’s dawn at length,

As its first rays flooded the world with light,

Showed the broad waters, glittering blue and bright,

And where, amid the leafy hawthorn wood,

Just as of old the low white convent stood.

Would any know her? Nay, no fear. Her face

Had lost all trace of youth, of joy, of grace,

Of the pure happy soul they used to know—

The novice Angela—so long ago.

She rang the convent bell. The well-known sound

Smote on her heart, and bowed her to the ground.

And she, who had not wept for long dry years,

Felt the strange rush of unaccustomed tears;

Terror and anguish seemed to check her breath,

And stop her heart O God! could this be death?

Crouching against the iron gate, she laid

Her weary head against the bars, and prayed:

But nearer footsteps drew, then seemed to wait;

And then she heard the opening of the grate,

And saw the withered face, on which awoke

Pity and sorrow, as the portress spoke,

And asked the stranger’s bidding: “Take me in,”

She faltered, “Sister Monica, from sin,

And sorrow, and despair, that will not cease;

Oh take me in, and let me die in peace!”

With soothing words the sister bade her wait,

Until she brought the key to unbar the gate.

The beggar tried to thank her as she lay,

And heard the echoing footsteps die away.

But what soft voice was that which sounded near,

And stirred strange trouble in her heart to hear?

She raised her head; she saw—she seemed to know

A face that came from long, long years ago:

Herself; yet not as when she fled away,

The young and blooming Novice, fair and gay,

But a grave woman, gentle and serene:

The outcast knew it—what she might have been.

But as she gazed and gazed, a radiance bright

Filled all the place with strange and sudden light;

The nun was there no longer, but instead,

A figure with a circle round its head,

A ring of glory; and a face, so meek,

So soft, so tender. . . . Angela strove to speak,

And stretched her hands out, crying, “Mary mild,

Mother of mercy, help me!—help your child!”

And Mary answered, “From thy bitter past,

Welcome, my child! oh, welcome home at last!

I filled thy place. Thy flight is known to none,

For all thy daily duties I have done;

Gathered thy flowers, and prayed, and sang, and slept;

Didst thou not know, poor child, thy place was kept?

Kind hearts are here; yet would the tenderest one

Have limits to its mercy: God has none.

A man’s forgiveness may be true and sweet,

But yet he stoops to give it. More complete

Is love that lays forgiveness at thy feet,

And pleads with thee to raise it. Only Heaven

Means crowned, not vanquished, when it says ‘Forgiven!’”

Back hurried Sister Monica; but where

Was the poor beggar she left lying there?

Gone; and she searched in vain, and sought the place

For that wan woman, with the piteous face:

But only Angela at the gateway stood,

Laden with hawthorn blossoms from the wood.

And never did a day pass by again,

But the old portress, with a sigh of pain,

Would sorrow for her loitering: with a prayer

That the poor beggar, in her wild despair,

Might not have come to any ill; and when

She ended, “God forgive her!” humbly then

Did Angela bow her head, and say “Amen!”

How pitiful her heart was! all could trace

Something that dimmed the brightness of her face

After that day, which none had seen before;

Not trouble—but a shadow—nothing more.

Years passed away. Then, one dark day of dread,

Saw all the sisters kneeling round a bed,

Where Angela lay dying; every breath

Struggling beneath the heavy hand of death.

But suddenly a flush lit up her cheek,

She raised her wan right hand, and strove to speak.

In sorrowing love they listened; not a sound

Or sigh disturbed the utter silence round;

The very taper’s flames were scarcely stirred,

In such hushed awe the sisters knelt and heard.

And thro’ that silence Angela told her life:

Her sin, her flight; the sorrow and the strife,

And the return; and then, clear, low, and calm,

“Praise God for me, my sisters;” and the psalm

Rang up to heaven, far, and clear, and wide,

Again and yet again, then sank and died;

While her white face had such a smile of peace,

They saw she never heard the music cease;

And weeping sisters laid her in the tomb,

Crowned with a wreath of perfumed hawthorn bloom.

And thus the legend ended. It may be

Something is hidden in the mystery,

Besides the lesson of God’s pardon, shown

Never enough believed, or asked, or known.

Have we not all, amid life’s petty strife,

Some pure ideal of a noble life

That once seemed possible? Did we not hear

The flutter of its wings, and feel it near,

And just within our reach? It was. And yet

We lost it in this daily jar and fret,

And now live idle in a vague regret;

But still our place is kept, and it will wait,

Ready for us to fill it, soon or late.

No star is ever lost we once have seen,

We always may be what we might have been.

Since good, tho’ only thought, has life and breath,

God’s life—can always be redeemed from death;

And evil, in its nature, is decay,

And any hour can blot it all away;

The hopes that, lost, in some far distance seem.

May be the truer life, and this the dream.

Word Count: 3484

This story is continued in The Haunted House, Part 5: The Ghost in the Cupboard Room.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Danny Daw

Posted

2 February 2022

Last modified

11 January 2025

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.