The Case of Lady Sannox

The Idler, vol. 4, issue 11 (1893)

Pages 330-342

Introductory Note: The Idler was a good fit for Doyle’s story, as it frequently published stories with a dark, mysterious tone alongside lighter, more humorous tales. At the time, Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series was immensely popular, giving “Lady Sannox” a prominent place at the front of the publication. Although this story has been largely overshadowed by Doyle’s more famous Holmes stories, it carries important insights into Victorian culture. The main character is easily identified as an aesthete and a part of the decadent movement, questioning the movement and its recent extremes; furthermore, Lady Sannox’s sad position at the end of the story contributes to Victorian debates about women and their legal status in society; finally, the inclusion of Turkish elements sheds light on the unsettled reactions Victorians had as they were confronted by new and foreign things during a time of increasing internationalism and exploration.

THE relations between Douglas Stone and the notorious Lady Sannox were very well known both among the fashionable circles of which she was a brilliant member, and the scientific bodies which numbered him among their most illustrious confrères. There was naturally, therefore, a very widespread interest when it was announced one morning that the lady had absolutely and for ever taken the veil, and that the world would see her no more. When, at the very tail of this rumour, there came the assurance that the celebrated operating surgeon, the man of steel nerves, had been found in the morning by his valet, seated on one side of his bed, smiling pleasantly upon the universe, with both legs jammed into one side of his breeches, and his great brain about as valuable as a cup full of porridge, the matter was strong enough to give quite a little thrill of interest to folk who had never hoped that their jaded nerves were capable of such a sensation.

Douglas Stone in his prime was one of the most remarkable men in England. Indeed, he could hardly be said to have ever reached his prime, for he was but nine-and-thirty at the time of this little incident. Those who knew him best were aware that, famous as he was as a surgeon, he might have succeeded with even greater rapidity in any of a dozen lines of life. He could have cut his way to fame as a soldier, struggled to it as an explorer, bullied for it in the courts, or built it out of stone and iron as an engineer. He was born to be great, for he could plan what another man dare not do, and he could do what another man dare not plan. In surgery none could follow him. His nerve, his judgment, his intuition, were things apart. Again and again his knife cut away death, but grazed the very springs of life in doing it, until his assistants were as white as the patient. His energy, his audacity, his full-blooded self-confidence—does not the memory of them still linger to the south of Marylebone Road and the north of Oxford Street?

And his vices were as magnificent as his virtues, and infinitely more picturesque. Large as was his income, and it was the third largest of all professional men in London, it was far beneath the luxury of his living. Deep in his complex nature lay a rich vein of sensualism, at the sport of which he placed all the prizes of his life. The eye, the ear, the touch, the palate, all were his masters. The bouquet of old vintages, the scent of rare exotics, the curves and tints of the daintiest potteries of Europe, it was to these that the quick-running stream of gold was transformed. And then there came his sudden mad passion for Lady Sannox, when a single interview with two challenging glances and a whispered word set him ablaze. She was the loveliest woman in London, and the only one to him. He was one of the handsomest men in London, but not the only one to her. She had a liking for new experiences, and was gracious to most men who wooed her. It may have been cause or it may have been effect that Lord Sannox looked fifty, though he was but six-and-thirty.

He was a quiet, silent, neutral-tinted man, with thin lips and heavy eyelids, much given to gardening, and full of quiet, home-like habits. He had at one time been fond of acting, had even rented a theatre in London, and on its boards had first seen Miss Marion Dawson, to whom he had offered his hand, his title, and the third of a county. Since his marriage this early hobby had become distasteful to him. Even in private theatricals it was no longer possible to persuade him to exercise the talent which he had often showed that he possessed. He was happier with a spud and a watering-can among his orchids and chrysanthemums.

It was quite an interesting problem whether he was absolutely devoid of sense, or miserably wanting in spirit. Did he know his lady’s ways and condone them, or was he a mere blind, doting fool? It was a point to be discussed over the teacups in snug little drawing-rooms, or with the aid of a cigar in the bow windows of clubs. Bitter and plain were the comments among the men upon his conduct. There was but one who had a good word to say for him, and he was the most silent member in the smoking-room. He had seen him break in a horse at the University, and it seemed to have left an impression upon his mind.

But when Douglas Stone became the favourite, all doubts as to Lord Sannox’s knowledge or ignorance were set for ever at rest. There was no subterfuge about Stone. In his high-handed, impetuous fashion, he set all caution and discretion at defiance. The scandal became notorious. A learned body intimated that his name had been struck from the list of its vice-presidents. Two friends implored him to consider his professional credit. He cursed them all three, and spent forty guineas on a bangle to take with him to the lady. He was at her house every evening, and she drove in his carriage in the afternoons. There was not an attempt on either side to conceal their relations; but there came at last a little incident to interrupt them.

It was a dismal winter’s night, very cold and gusty, with the wind whooping in the chimneys, and blustering against the window-panes. A thin spatter of rain tinkled on the glass with each fresh sough of the gale, drowning for the instant the dull gurgle and drip from the eaves. Douglas Stone had finished his dinner, and sat by his fire in the study, a glass of rich port upon the malachite table at his elbow. As he raised it to his lips, he held it up against the lamplight, and watched with the eye of a connoisseur the tiny scales of beeswing which floated in its rich ruby depths. The fire, as it spurted up, threw fitful lights upon his bold, clear-cut face, with its widely-opened grey eyes, its thick and yet firm lips, and the deep square jaw, which had something Roman in its strength and its animalism. He smiled from time to time as he nestled back in his luxurious chair. Indeed, he had a right to feel well pleased, for against the advice of six colleagues, he had performed an operation that day of which only two cases were on record, and the result had been brilliant beyond all expectation. No other man in London would have had the daring to plan, or the skill to execute, such a heroic measure.

But he had promised Lady Sannox to see her that evening, and it was already half-past eight. His hand was outstretched to the bell to order the carriage when he heard the dull thud of the knocker. An instant later there was the shuffling of feet in the hall, and the sharp closing of a door.

“A patient to see you, sir, in the consulting room,” said the butler.

“About himself?”

“No, sir, I think he wants you to go out.”

“It is too late,” cried Douglas Stone peevishly, “I won’t go.”

“This is his card, sir.” The butler presented it upon the gold salver which had been given to his master by the wife of a Prime Minister.

“‘Hamil Ali, Smyrna.’ Hum! The fellow is a Turk, I suppose.”

“Yes, sir. He seems as if he came from abroad, sir. And he’s in a terrible way.”

“Tut, tut! I have an engagement. I must go somewhere else. But I’ll see him. Show him in here, Pim.”

A few moments later the butler swung open the door and ushered in a small and decrepid man, who walked with a bent back and with the forward push of the face and blink of the eyes which goes with extreme short sight.1For “of the,” the original reads “o fthe.” His face was swarthy, and his hair and beard of the deepest black. In one hand he held a turban of white muslin striped with red, in the other a small chamois leather bag.

“Good evening,” said Douglas Stone, when the butler had closed the door. “You speak English, I presume?”

“Yes, sir. I am from Asia Minor, but I speak English when I speak slow.”

“You wanted me to go out, I understand?”

“Yes, sir. I wanted very much that you should see my wife.”

“I could come in the morning, but I have an engagement which prevents me from seeing your wife to-night.”

The Turk’s answer was a singular one. He pulled the string which closed the mouth of the chamois leather bag, and poured a flood of gold on to the table.

“There are one hundred pounds there,” said he, “and I promise you that it will not take you an hour. I have a cab ready at the door.”

Douglas Stone glanced at his watch. An hour would not make it too late to visit Lady Sannox. He had been there later. And the fee was an extraordinarily high one. He had been pressed by his creditors lately, and he could not afford to let such a chance pass. He would go.

“What is the case?” he asked.

“Oh, it is so sad a one! So sad a one! You have not, perhaps, heard of the daggers of the Almohades?”2An Islamic Caliphate that ruled much of North Africa and Spain in the 12th century.

“Never.”

“Ah, they are Eastern daggers of a great age, and of a singular shape, with the hilt like what you call a stirrup. I am a curiosity dealer, you understand, and that is why I have come to England from Smyrna, but next week I go back once more. Many things I brought with me, and I have few things left, but among them, to my sorrow, is one of these daggers.”

“You will remember that I have an appointment, sir,” said the surgeon, with some irritation. “Pray confine yourself to the necessary details.”

“You will see that it is necessary. To-day my wife fell down in a faint in the room in which I keep my wares, and she cut her lower lip upon this cursed dagger of Almohades.”

“I see,” said Douglas Stone, rising. “And you wish me to dress the wound?”

“No, no, it is worse than that.”

“What then?”

“These daggers are poisoned.”

“Poisoned!”

“Yes, and there is no man, East or West, who can tell now what is the poison or what the cure. But all that is known I know, for my father was in this trade before me, and we have had much to do with these poisoned weapons.”

“What are the symptoms?”

“Deep sleep, and death in thirty hours.”

“And you say there is no cure. Why then should you pay me this considerable fee?”

“No drug can cure, but the knife may.”

“And how?”

“The poison is slow of absorption. It remains for hours in the wound.”

“Washing, then, might cleanse it?”3The original places a single closing quotation mark rather than double quotation marks at the end of this sentence.

“No more than in a snake bite. It is too subtle and too deadly.”

“Excision of the wound, then?”

“That is it. If it be on the finger, take the finger off. So said my father always. But think of where this wound is, and that it is my wife. It is dreadful!”

But familiarity with such grim matters may take the finer edge from a man’s sympathy. To Douglas Stone this was already an interesting case, and he brushed aside as irrelevant the feeble objections of the husband.

“It appears to be that or nothing,” said he, brusquely. “It is better to lose a lip than a life.”

“Ah, yes, I know that you are right. Well, well, it is kismet, and it must be faced. I have the cab, and you will come with me and do this thing.”

Douglas Stone took his case of bistourie from a drawer, and placed it with a roll of bandage and a compress of lint in his pocket.4Bistourie (Old French): scalpel He must waste no more time if he were to see Lady Sannox.

“I am ready,” said he, pulling on his overcoat. “Will you take a glass of wine before you go out into this cold air?”

His visitor shrunk away, with a protesting hand upraised.

“You forget that I am a Mussulman, and a true follower of the Prophet,” said he. “But tell me what is the bottle of green glass which you have placed in your pocket?”

“It is chloroform.”

“Ah, that also is forbidden to us. It is a spirit, and we make no use of such things.”

“What! You would allow your wife to go through an operation without an anæsthetic?”

“Ah! she will feel nothing, poor soul. The deep sleep has already come on, which is the first working of the poison. And then I have given her of our Smyrna opium. Come, sir, for already an hour has passed.”

As they stepped out into the darkness, a sheet of rain was driven in upon their faces, and the hall lamp, which dangled from the arm of a marble Caryatid, went out with a fluff. Pim, the butler, pushed the heavy door to, straining hard with his shoulder against the wind, while the two men groped their way towards the yellow glare which showed where the cab was waiting. An instant later they were rattling upon their journey.

“Is it far?” asked Douglas Stone.

“Oh, no. We have a very little quiet place off the Euston Road.”

The surgeon pressed the spring of his repeater and listened to the little tings which told him the hour. It was a quarter past nine. He calculated the distances, and the short time which it would take him to perform so trivial an operation. He ought to reach Lady Sannox by ten o’clock. Through the fogged windows he saw the blurred gas lamps dancing past, with occasionally the broader glare of a shop front. The rain was pelting and rattling upon the leathern top of the carriage, and the wheels swashed as they rolled through puddle and mud. Opposite to him the white headgear of his companion gleamed faintly through the obscurity. The surgeon felt in his pockets and arranged his needles, his ligatures, and his safety-pins that no time might be wasted when they arrived. He chafed with impatience and drummed his foot upon the floor.

But the cab slowed down at last and pulled up. In an instant Douglas Stone was out, and the Smyrna merchant’s toe was at his very heel. “You can wait,” said he to the driver. It was a mean-looking house in a narrow and sordid street. The surgeon, who knew his London well, cast a swift glance into the shadows, but there was nothing distinctive, no shop, no movement, nothing but a double line of dull flat-faced houses, a double stretch of wet flagstones which gleamed in the lamplight, and a double rush of water in the gutters which swirled and gurgled towards the sewer gratings. The door which faced them was blotched and discoloured, and a faint light in the fan pane above it served to show the dust and the grime which covered it. Above, in one of the bedroom windows, there was a dull yellow glimmer. The merchant knocked loudly, and, as he turned his dark face towards the light, Douglas Stone could see that it was contracted with anxiety. A bolt was drawn, and an elderly woman with a taper stood in the doorway, shielding the thin flame with her gnarled hand.

“Is all well?” gasped the merchant.

“She is as you left her, sir.”

“She has not spoken?”

“No, she is in a deep sleep.”

The merchant closed the door, and Douglas Stone walked down the narrow passage, glancing about him in some surprise as he did so. There was no oilcloth, no mat, no hat-rack. Deep gray dust and heavy festoons of cobwebs met his eyes everywhere. Following the old woman up the winding stair, his firm footfall echoed harshly through the silent house. There was no carpet.

The bedroom was on the second landing. Douglas Stone followed the old nurse into it, with the merchant at his heels. Here, at least, there was furniture and to spare. The floor was littered and the corners piled with Turkish cabinets, inlaid tables, coats of chain mail, strange pipes, and grotesque weapons. A single small lamp stood upon a bracket on the wall. Douglas Stone took it down, and, picking his way among the lumber, walked over to a couch in the corner, on which lay a woman dressed in the Turkish fashion, with yashmak and veil. The lower part of the face was exposed, and the surgeon saw a jagged cut which zigzagged along the border of the under lip.

“You will forgive the yashmak,” said the Turk. “You know our views about woman in the East.”

But the surgeon was not thinking about the yashmak. This was no longer a woman to him. It was a case. He stooped and examined the wound carefully.

“There are no signs of irritation,” said he. “We might delay the operation until local symptoms develop.”

The husband wrung his hands in incontrollable agitation.

“Oh! sir, sir,” he cried. “Do not trifle. You do not know. It is deadly. I know, and I give you my assurance that an operation is absolutely necessary. Only the knife can save her.”

“And yet I am inclined to wait,” said Douglas Stone.

“That is enough,” the Turk cried, angrily. “Every minute is of importance, and I cannot stand here and see my wife allowed to sink. It only remains for me to give you my thanks for having come, and to call in some other surgeon before it is too late.”

Douglas Stone hesitated. To refund that hundred pounds was no pleasant matter. But of course if he left the case he must return the money. And if the Turk were right and the woman died his position before a coroner might be an embarrassing one.

“You have had personal experience of this poison?” he asked.

“I have.”

“And you assure me that an operation is needful.”

“I swear it by all that I hold sacred.”

“The disfigurement will be frightful.”

“I can understand that the mouth will not be a pretty one to kiss.”

Douglas Stone turned fiercely upon the man. The speech was a brutal one. But the Turk has his own fashion of talk and of thought, and there was no time for wrangling. Douglas Stone drew a bistoury from his case, opened it, and felt the keen straight edge with his forefinger.5Bistoury: The English translation of the Old French word for “scalpel” defined in an earlier footnote. Why the narrator uses both forms of the word is unknown. Then he held the lamp closer to the bed. Two dark eyes were gazing up at him through the slit in the yashmak. They were all iris, and the pupil was hardly to be seen.

“You have given her a very heavy dose of opium.”

“Yes, she has had a good dose.”

He glanced again at the dark eyes which looked straight at his own. They were dull and lustreless, but, even as he gazed, a little shifting sparkle came into them, and the lips quivered.

“She is not absolutely unconscious,” said he.

“Would it not be well to use the knife while it will be painless?”

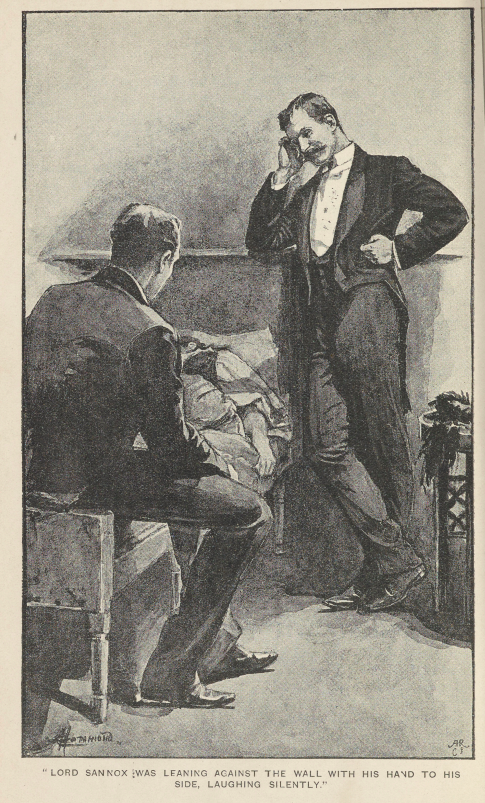

The same thought had crossed the surgeon’s mind. He grasped the wounded lip with his forceps, and with two swift cuts he took out a broad V shaped piece. The woman sprang up on the couch with a dreadful gurgling scream. Her covering was torn from her face. It was a face that he knew. In spite of that protruding upper lip and that slobber of blood, it was a face that he knew. She kept on putting her hand up to the gap and screaming. Douglas Stone sat down at the foot of the couch with his knife and his forceps. The room was whirling round, and he had felt something go like a ripping seam behind his ear. A bystander would have said that his face was the more ghastly of the two. As in a dream, or as if he had been looking at something at the play, he was conscious that the Turk’s hair and beard lay upon the table, and that Lord Sannox was leaning against the wall with his hand to his side, laughing silently. The screams had died away now, and the dreadful head had dropped back again upon the pillow, but Douglas Stone still sat motionless, and Lord Sannox still chuckled quietly to himself.

“It was really very necessary for Marion, this operation,” said he, “not physically, but morally, you know, morally.”

Douglas Stone stooped forwards and began to play with the fringe of the coverlet. His knife tinkled down upon the ground, but he still held the forceps and something more.

“I had long intended to make a little example,” said Lord Sannox, suavely. “Your note of Wednesday miscarried, and I have it here in my pocket-book. I took some pains in carrying out my idea. The wound, by the way, was from nothing more dangerous than my signet ring.”

He glanced keenly at his silent companion, and cocked the small revolver which he held in his coat pocket. But Douglas Stone was still picking at the coverlet.

“You see you have kept your appointment after all,” said Lord Sannox.

And at that Douglas Stone began to laugh. He laughed long and loudly. But Lord Sannox did not laugh now. Something like fear sharpened and hardened his features. He walked from the room, and he walked on tiptoe. The old woman was waiting outside.

“Attend to your mistress when she awakes,” said Lord Sannox. Then he went down to the street. The cab was at the door, and the driver raised his hand to his hat.

“John,” said Lord Sannox, “you will take the doctor home first. He will want leading downstairs, I think. Tell his butler that he has been taken ill at a case.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Then you can take Lady Sannox home.”

“And how about yourself, sir?”

“Oh, my address for the next few months will be Hotel di Roma, Venice. Just see that the letters are sent on. And tell Stevens to exhibit all the purple chrysanthemums next Monday, and to wire me the result.”

Word Count: 4054

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Arthur Conan Doyle. “The Case of Lady Sannox.” The Idler, vol. 4, no. 11, 1893, pp. 330-42. Edited by David Moberly. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 12 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-case-of-lady-sannox/.

Editors

David Moberly

Isaac Robertson

Alayna Een

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

13 July 2020

Last modified

10 July 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | For “of the,” the original reads “o fthe.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | An Islamic Caliphate that ruled much of North Africa and Spain in the 12th century. |

| ↑3 | The original places a single closing quotation mark rather than double quotation marks at the end of this sentence. |

| ↑4 | Bistourie (Old French): scalpel |

| ↑5 | Bistoury: The English translation of the Old French word for “scalpel” defined in an earlier footnote. Why the narrator uses both forms of the word is unknown. |