The Home-Coming

The Strand Magazine, vol. 38, issue 223 (1909)

Pages 646-654

Introductory Note: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s adventure story embodies the unique Victorian progressivism championed by The Strand, a massively popular periodical that primarily targeted a mass market, middle-class family readership. The Strand published stories that featured fallen women in positions of power, lower-class protagonists, and depictions of gender and identity that pushed against the more traditional definitions of the day. However, its stories were framed in conservative terms. While “The Home-Coming” incorporates this progressive rhetoric, its aesthetic is indelibly conservative. Basil, the story’s antagonist, is described in pejoratively feminine terms, a stark contrast to the Empress Theodora, a lower-class fallen woman who is nevertheless in a position of great power. Doyle, and by extension The Strand, consequently presents readers with a view of progressivism tempered by conservative social terms.

Advisory: This story contains racist and ableist language, along with depictions of slavery.

In the spring of the year 528 a small brig used to run as a passenger-boat between Chalcedon, on the Asiatic shore, and Constantinople. On the morning in question, which was that of the Feast of St. George, the vessel was crowded with excursionists who were bound for the great city in order to take part in the religious and festive celebrations which marked the festival of the Megalo-martyr, one of the most choice occasions in the whole vast hagiology of the Eastern Church. The day was fine and the breeze light, so that the passengers in their holiday mood were able to enjoy without a qualm the many objects of interest which marked the approach to the greatest and most beautiful capital in the world.

On the right, as they sped up the narrow strait, there stretched the Asiatic shore, sprinkled with white villages and with numerous villas peeping out from the woods which adorned it. In front of them, the Prince’s Islands, rising as green as emeralds out of the deep sapphire blue of the Sea of Marmora, obscured for the moment the view of the capital. As the brig rounded these the great city burst suddenly upon their sight and a murmur of admiration and wonder rose from the crowded deck. Tier above tier it lay, white and glittering, a hundred brazen roofs and gilded statues gleaming in the sun, with high over all the magnificent shining cupola of St. Sophia. Seen against a cloudless sky, it was the city of a dream—too delicate, too airily lovely for earth.

In the prow of the small vessel were two travellers of singular appearance. The one was a very beautiful boy, ten or twelve years of age, swarthy, clear-cut, with dark, curling hair and vivacious black eyes, full of intelligence and of the joy of living. The other was an elderly man, gaunt-faced and grey-bearded, whose stern features were lit up by a smile as he observed the excitement and interest with which his young companion viewed the beautiful distant city and the many vessels which thronged the narrow strait.

“See! See!” cried the lad. “Look at the great red ships which sail out from yonder harbour. Surely, your Holiness, they are the greatest of all ships in the world!”

The old man, who was the Abbot of the Monastery of St. Nicephorus in Antioch, laid his hand upon the boy’s shoulder.

“Be wary, Leon, and speak less loudly, for until we have seen your mother we should keep ourselves secret. As to the red galleys, they are indeed as large as any, for they are the Imperial ships of war, which come forth from the harbour of Theodosius. Round yonder green point is the Golden Horn, where the merchant ships are moored. But now, Leon, if you follow the line of buildings past the great church you will see a long row of pillars fronting the sea. It marks the Palace of the Cæsars.”

The boy looked at it with fixed attention.

“And my mother is there?” he whispered.

“Yes, Leon; your mother the Empress Theodora and her husband, the great Justinian, dwell in yonder palace.”

The boy looked wistfully up into the old man’s face.

“Are you sure, Father Luke, that my mother will indeed be glad to see me?”

The Abbot turned away his face to avoid those questioning eyes.

“We cannot tell, Leon. We can only try. If it should prove that there is no place for you, then there is always a welcome among the brethren of St. Nicephorus.”

“Why did you not tell my mother that we were coming Father Luke? Why did you not wait until you had her command?”

“At a distance, Leon, it would be easy to refuse you. An Imperial messenger would have stopped us. But when she sees you, Leon—your eyes, so like her own; your face which carries memories of one whom she loved—then, if there be a woman’s heart within her bosom, she will take you into it. They say that the Emperor can refuse her nothing. They have no child of their own. There is a great future before you, Leon. When it comes, do not forget the poor brethren of St. Nicephorus, who took you in when you had no friend in the world.”

The old Abbot spoke cheerily, but it was easy to see from his anxious countenance that the nearer he came to the capital the more doubtful did his errand appear. What had seemed easy and natural from the quiet cloisters of Antioch became dubious and dark now that the golden domes of Constantinople glittered so close at hand.

Ten years before, a wretched woman, whose very name was an offence throughout the Eastern world where she was as infamous for her dishonour as famous for her beauty, had come to the monastery gate and had persuaded the monks to take charge of her infant son, the child of her shame. There he had been ever since. But she, Theodora the wanton, returning to the capital, had, by the strangest turn of Fortune’s wheel, caught the fancy and, finally, the enduring love of Justinian, the heir to the throne. Then on the death of his uncle the young man had become the greatest monarch upon the earth, and had raised Theodora to be not only his wife and Empress, but to be absolute ruler, with powers equal to and independent of his own. And she, the polluted one, had risen to the dignity, had cut herself sternly away from all that related to her past life, and had showed signs already of being a great Queen, stronger and wiser than her husband, but fierce, vindictive, and unbending, a firm support to her friends, but a terror to her foes. This was the woman to whom the Abbot Luke of Antioch was bringing Leon, her forgotten son. If ever her mind strayed back to the days when, abandoned by her lover Ecebolus, the Governor of the African Pentapolis, she had made her way on foot through Asia Minor and left her infant with the monks, it was only to persuade herself that the brethren cloistered far from the world would never identify Theodora the Empress with Theodora the dissolute wanderer, and that the fruits of her sin would be for ever concealed from her Imperial husband.

The little brig had now rounded the point of the Acropolis, and the long blue stretch of the Golden Horn lay before it. The high wall of Theodosius lined the whole harbour, but a narrow verge of land had been left between it and the water’s edge to serve as a quay. The vessel ran alongside near the Neorion Gate, and the passengers, after a short scrutiny from the group of helmeted guards who lounged beside it, were allowed to pass through into the great city.

The Abbot, who had made several visits to Constantinople upon the business of his monastery, walked with the assured step of one who knows his ground; while the boy, alarmed and yet pleased by the rush of people, the roar and clatter of passing chariots, and the vista of magnificent buildings, held tightly to the loose gown of his guide, while staring eagerly about him in every direction. Passing through the steep and narrow streets which lead up from the water, they emerged into the open space which surrounds the magnificent pile of St. Sophia, the great shrine begun by Constantine, hallowed by St. Chrysostom, and now the seat of the Patriarch and the very centre of the Eastern Church. Only with many crossings and genuflexions did the pious Abbot succeed in passing the revered shrine of his religion and hurrying on to his difficult task.

Having passed St. Sophia, the two travellers crossed the marble-paved Augusteum, and saw upon their right the gilded gates of the Hippodrome, through which a vast crowd of people was pressing; for though the morning had been devoted to the religious ceremony, the afternoon was given over to the secular festivities. So great was the rush of the populace that the two strangers had some difficulty in disengaging themselves from the stream and reaching the huge arch of black marble which formed the outer gate of the Palace. Within they were fiercely ordered to halt by a gold-crested and magnificent sentinel, who laid his shining spear across their breasts until his superior officer should give them permission to pass. The Abbot had been warned, however, that all obstacles would give way if he mentioned the name of Basil the Eunuch, who acted as Chamberlain of the Palace and also as Parakimomen—a high office which meant that he slept at the door of the Imperial bedchamber. The charm worked wonderfully, for at the mention of that potent name the Protosphathaire, or head of the Palace Guards, who chanced to be upon the spot, immediately detached one of his soldiers with instructions to convoy the two strangers into the presence of the Chamberlain.

Passing in succession a middle guard and an inner guard, the travellers came at last into the Palace proper, and followed their majestic guide from chamber to chamber, each more wonderful than the last. Marbles and gold, velvet and silver, glittering mosaics, wonderful carvings, ivory screens, curtains of Armenian tissue and of Indian silk, damask from Arabia and amber from the Baltic—all these things merged themselves in the minds of the two simple provincials, until their eyes ached and their senses reeled before the blaze and the glory of this most magnificent of the dwellings of man. Finally, a pair of curtains, crusted with gold, were parted, and their guide handed them over to a negro mute, who stood within. A heavy, fat, brown-skinned man, with a large, flabby, hairless face, was pacing up and down the small apartment, and he turned as they entered with an abominable and threatening smile. His loose lips and pendulous cheeks were those of a gross old woman, but above them there shone a pair of dark, malignant eyes, full of fierce intensity of observation and judgment.

“You have entered the palace by using my name,” he said. “It is one of my boasts that any of the populace can approach me in this way. But it is not fortunate for those who take advantage of it without due cause.” Again he smiled a smile which made the frightened boy cling tightly to the loose serge skirts of the Abbot.

But the ecclesiastic was a man of courage. Undaunted by the sinister appearance of the great Chamberlain, or by the threat which lay in his words, he laid his hand upon his young companion’s shoulder and faced the eunuch with a confident smile.

“I have no doubt, your Excellency,” said he, “that the importance of my mission has given me the right to enter the Palace. The only thing which troubles me is whether it may not be so important as to forbid me from broaching it to you, or, indeed, to anybody save the Empress Theodora, since it is she only whom it concerns.”

The eunuch’s thick eyebrows bunched together over his vicious eyes.

“You must make good those words,” he said. “If my gracious master—the ever-glorious Emperor Justinian—does not disdain to take me into his most intimate confidence in all things, it would be strange if there were any subject within your knowledge which I might not hear. You are, as I gather from your garb and bearing, the Abbot of some Asiatic monastery?”

“You are right, your Excellency. I am the Abbot of the Monastery of St. Nicephorus in Antioch. But I repeat that I am assured that what I have to say is for the ear of the Empress Theodora only.”

The eunuch was evidently puzzled and his curiosity aroused by the old man’s persistence. He came nearer, his heavy face thrust forward, his flabby brown hands, like two sponges, resting upon the table of yellow jasper before him.

“Old man,” said he, “there is no secret which concerns the Empress which may not be told to me. But if you refuse to do so, it is certain that you will never see her. Why should I admit you unless I know your errand? How should I know that you are not a Manichean heretic with a poniard in your bosom, longing for the blood of the mother of the Church?”

The Abbot hesitated no longer.

“If there is a mistake in the matter, then, on your head be it,” said he. “Know then that this lad Leon is the son of Theodora the Empress, left by her in our monastery within a month of his birth ten years ago. This papyrus which I hand you will show you that what I say is beyond all question or doubt.”

The Eunuch Basil took the paper, but his eyes were fixed upon the boy, and his features showed a mixture of amazement at the news that he had received and of cunning speculation as to how he could turn it to profit.

“Indeed, he is the very image of the Empress,” he muttered; and then, with sudden suspicion: “Is it not the chance of this likeness which has put the scheme into your head, old man?”

“There is but one way to answer that,” said the Abbot. “It is to ask the Empress herself whether what I say is not true, and to give her the glad tidings that her boy is alive and well.”

The tone of confidence, together with the testimony of the papyrus and of the boy’s beautiful face, removed the last shadow of doubt from the eunuch’s mind. Here was a great fact, but what use could he make of it? Above all, what advantage could he draw from it? He stood with his fat chin in his hand, turning it over in his cunning brain.

“Old man,” said he at last, “to how many have you told this secret?”

“To no one in the whole world,” the other answered. “There is Deacon Bardas at the monastery and myself. No one else knows anything.”

“You are sure of this?”

“Absolutely certain.”

The eunuch had made up his mind. If he alone of all men in the Palace knew of this event he would have a powerful hold over his masterful mistress. He was certain that Justinian the Emperor knew nothing of it. It would be a shock to him. It might even alienate his affections from his wife. She might care to take precautions to prevent him from knowing. And if he, Basil the Eunuch, was her confederate in these precautions, then how very close it must draw him to her. All this flashed through his mind as he stood, the papyrus in his hand, looking at the old man and the boy.

“Stay here,” said he. “I will be with you again.” With a swift rustle of his silken robes he swept from the chamber.

A few minutes had elapsed when a curtain at the end of the room was pushed aside, and the eunuch, reappearing, held it back, doubling his unwieldy body into a profound obeisance as he did so. Through the gap came a small, alert woman, clad in golden tissue, with a loose outer mantle and shoes of the Imperial purple. That colour alone showed that she could be none other than the Empress; but the dignity of her carriage, the fierce authority of her magnificent dark eyes, and the perfect beauty of her haughty face, all proclaimed that it could only be that Theodora who, in spite of her lowly origin, was the most majestic as well as the most maturely lovely of all the women in her kingdom. Gone now were the buffoon tricks which the daughter of Acacius the bear-ward had learned in the Amphitheatre; gone, too, was the light charm of the wanton, and what was left was the worthy mate of a great King, the measured dignity of one who was every inch an Empress.

Disregarding the two men, Theodora walked up to the boy, placed her two white hands upon his shoulders, and looked with a long, questioning gaze — a gaze which began with hard suspicion and ended with tender recognition — into those large, lustrous eyes which were the very reflection of her own. At first the sensitive lad was chilled by the cold, intent question of the look; but as it softened his own spirit responded, until suddenly, with a cry of “Mother! mother!” he cast himself into her arms, his hands locked round her neck, his face buried in her bosom. Carried away by the sudden natural outburst of emotion, her own arms tightened round the lad’s figure, and she strained him for an instant to her heart. Then, the strength of the Empress gaining instant command over the temporary weakness of the mother, she pushed him back from her, and waved that they should leave her to herself. The slaves in attendance hurried the two visitors from the room. Basil the Eunuch lingered, looking down at his mistress, who had thrown herself upon a damask couch, her lips white and her bosom heaving with the tumult of her emotion. She glanced up and met the Chamberlain’s crafty gaze, her woman’s instinct reading the threat that lurked within it.

“I am in your power,” she said. “The Emperor must never know of this.”

“I am your slave,” said the eunuch, with his ambiguous smile. “I am an instrument in your hand. If it is your will that the Emperor should know nothing, then who is to tell him?”

“But the monk, the boy? What are we to do?”

“There is only one way for safety,” said the eunuch.

She looked at him with horrified eyes. His spongy hands were pointing down to the floor. There was an underground world to this beautiful Palace, a shadow that was ever close to the light, a region of dimly-lit passages, of shadowed corners, of noiseless, tongueless slaves, of sudden, sharp screams in the darkness. To this the eunuch was pointing.

A terrible struggle rent her breast. The beautiful boy was hers, flesh of her flesh, bone of her bone. She knew it beyond all question or doubt. He was her one child, and her whole heart went out to him. But Justinian! She knew the Emperor’s strange limitations. Her career in the past was forgotten. He had swept it all aside by special Imperial decree published throughout the Empire, as if she were new born through the power of his will and her association with his person. But they were childless, and this sight of one which was not his own would cut him to the quick. He could dismiss her infamous past from his mind, but if it took the concrete shape of this beautiful child, how then could he wave it aside as if it had never been? All her instincts and her intimate knowledge of the man told her that even her charm and her influence might fail under such circumstances to save her from ruin. Her divorce would be as easy to him as her elevation had been. She was balanced upon a giddy pinnacle, the highest in the world, and yet the higher the deeper the fall. Everything that earth could give was now at her feet. Was she to risk the losing of it all—for what? For a weakness which was unworthy of an Empress, for a foolish new-born spasm of love, for that which had no existence within her in the morning. How could she be so foolish as to risk losing such a substance for such a shadow?

“Leave it to me,” said the brown, watchful face above her.

“Must it be—death?”

“There is no real safety outside. But if your heart is too merciful, then by the loss of sight and speech—”

She saw in her mind the white-hot iron approaching those glorious eyes, and she shuddered at the thought.

“No, no, better death than that!”

“Let it be death, then. You are wise, great Empress, for there only is real safety and assurance of silence.”

“And the monk?”

“Him also.”

“But the Holy Synod! He is a tonsured priest. What would the Patriarch do?”

“Silence his babbling tongue. Then let them do what they will. How are we of the Palace to know that this conspirator, taken with a dagger in his sleeve, is really what he says?”

Again she shuddered and shrank down among the cushions.

“Speak not of it, think not of it,” said the eunuch. “Say only that you leave it all in my hands. Nay, then, if you cannot say it do but nod your head, and I take it as your signal.”

In that moment there flashed before Theodora’s mind a vision of all her enemies, of all those who envied her rise, of all whose hatred and contempt would rise into a clamour of delight could they see the daughter of the bear-ward hurled down again into that abyss from which she had been dragged. Her face hardened, her lips tightened, her little hands clenched in the agony of her thought.

“Do it!” she said.

In an instant, with a terrible smile, the messenger of death hurried from the room. She groaned aloud and buried herself yet deeper amid the silken cushions, clutching them frantically with convulsed and twitching hands.

The eunuch wasted no time, for this deed once done he became—save for some insignificant monk in Asia Minor, whose fate would soon be sealed—the only sharer of Theodora’s secret, and therefore the only person who could curb and bend that most imperious nature. Hurrying into the chamber where the visitors were waiting, he gave a sinister signal, only too well known in those iron days. In an instant the black mutes in attendance seized the old man and the boy, pushing them swiftly down a passage and into a meaner portion of the Palace, where the heavy smell of luscious cooking proclaimed the neighbourhood of the kitchens. A side corridor led to a heavily-barred iron door, and this in turn opened upon a steep flight of stone steps, feebly illuminated by the glimmer of wall-lamps. At the head and foot stood a mute sentinel like an ebony statue, and below, along the dusky and forbidding passages from which the cells opened, a succession of niches in the wall were each occupied by a similar guardian. The unfortunate visitors were dragged brutally down a number of stone-flagged and dismal corridors until they descended another long stair, which led so deeply into the earth that the damp feeling in the heavy air and the drip of water all round showed that they had come down to the level of the sea. Groans and cries like those of sick animals from the various grated doors which they passed showed how many there were who spent their whole lives in this humid and poisonous atmosphere.

At the end of this lowest passage was a door which opened into a single large vaulted room. It was devoid of furniture, but in the centre was a large and heavy wooden board clamped with iron. This lay upon a rude stone parapet, engraved with inscriptions beyond the wit of the Eastern scholars, for this old well dated from a time before the Greeks founded Byzantium, when men of Chaldea and Phœnicia built with huge unmortared blocks far below the level of the town of Constantine. The door was closed, and the eunuch beckoned to the slaves that they should remove the slab which covered the well of death. The frightened boy screamed and clung to the Abbot, who, ashy-pale and trembling, was pleading hard to melt the heart of the ferocious eunuch.

“Surely, surely, you would not slay the innocent boy!” he cried. “What has he done? Was it his fault that he came here? I alone—I and Deacon Bardas are to blame. Punish us if someone must indeed be punished. We are old. It is to-day or to-morrow with us. But he is so young and so beautiful, with all his life before him. Oh, sir—oh, your Excellency—you would not have the heart to hurt him.” He threw himself down and clutched at the eunuch’s knees, while the boy sobbed piteously and cast horror-stricken eyes at the black slaves who were tearing the wooden slab from the ancient parapet beneath. The only answer which the Chamberlain gave to the frantic pleadings of the Abbot was to take a stone which lay on the coping of the well and toss it in. It could be heard clattering against the old, damp, mildewed walls, until it fell with a hollow boom into some far-distant subterranean pool. Then he again motioned with his hands, and the black slaves threw themselves upon the boy and dragged him away from his guardian. So shrill was his clamour that no one heard the approach of the Empress. With a swift rush she had entered the room, and her arms were round her son.

“It shall not be! It cannot be!” she cried. “No, no, my darling, my darling; they shall do you no hurt! I was mad to think of it, mad and wicked to dream of it. Oh, my sweet boy, to think that your mother might have had your blood upon her head!”

The eunuch’s brows were gathered together at this failure of his plans, at this fresh example of feminine caprice.

“Why kill them, great lady, if it pains your gracious heart?” said he. “With a knife and a branding iron they can be disarmed for ever.”

She paid no attention to his words.

“Kiss me, Leon,” she cried. “just once let me feel my own child’s soft lips rest upon mine. Now again! No, no more, or I shall weaken for what I have still to say and still to do. Old man, you are very near a natural grave, and I cannot think, from your venerable aspect, that words of falsehood would come readily to your lips. You have indeed kept my secret all these years, have you not?”

“I have in very truth, great Empress. I swear to you by St. Luke, patron of our house, that, save old Deacon Bardas, there is none who knows.”

“Then let your lips still be sealed. If you have kept faith in the past, I see no reason why you should be a babbler in the future. And you, Leon”—she bent her wonderful eyes with a strange mixture of sternness and of love upon the boy—“can I trust you? Will you keep a secret which could never help you, but would be the ruin and downfall of your mother?”

“Oh, mother, I would not hurt you! I swear that I will be silent.”

“Then I trust you both. Such provision will be made for your monastery and for your own personal comforts as will make you bless the day you came to my Palace. Now you may go. I wish never to see you again. If I did you might find me in a softer mood, or in harder, and the one would lead to my undoing, the other to yours. But if by whisper or rumour I have reason to think that you have failed me, then you and your monks and your monastery will have such an end as will be a lesson for ever to those who would break faith with their Empress.”

“I will never speak,” said the old Abbot, “neither will Deacon Bardas. Neither will Leon. For all I can answer. But there are others, these slaves, the Chamberlain—we may be punished for another’s fault.”

“Not so,” said the Empress, and her eyes set like flints. “These slaves are voiceless, nor have they any means to tell those secrets which they know. As to you, Basil——” she raised her white hand with the same deadly gesture which he had himself used so short a time before. The black slaves were on him like hounds on a stag.

“Oh, my gracious mistress, dear lady, what is this? What is this? You cannot mean it!” he screamed, in his high cracked voice. “Oh, what have I done? Why should I die?”

“You have turned me against my own. You have goaded me to slay my own son. You have intended to use my secret against me. I read it in your eyes from the first. Cruel, murderous villain, taste the fate which you have yourself given to so many others. This is your doom. I have spoken.”

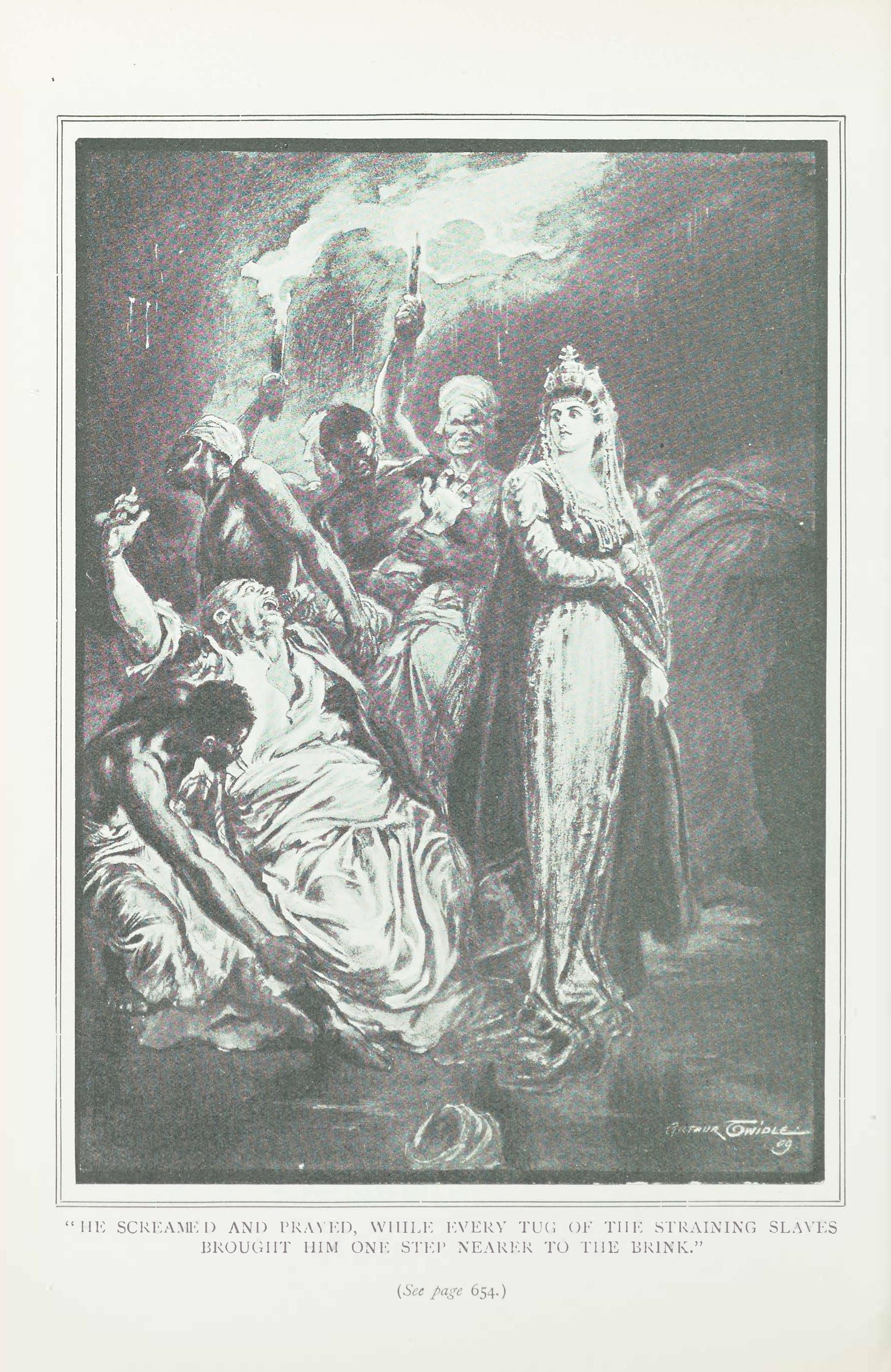

The old man and the boy hurried in horror from the vault. As they glanced back they saw the erect, inflexible, shimmering, gold-clad figure of the Empress. Beyond they had a glimpse of the green-scummed lining of the well, and of the great red open mouth of the eunuch as he screamed and prayed, while every tug of the straining slaves brought him one step nearer to the brink. With their hands over their ears they rushed away, but even so they heard that last woman-like shriek, and then the heavy plunge far down in the dark abysses of the earth.

Word Count: 5089

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

Arthur Conan Doyle. “The Home-Coming.” The Strand Magazine, vol. 38, no. 223, 1909, pp. 646-54. Edited by Taylor Flickinger. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 27 February 2026, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/the-home-coming/.

Editors

Taylor Flickinger

Sarah Henderson

Patrick Lamoureux

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Posted

20 March 2020

Last modified

25 February 2026