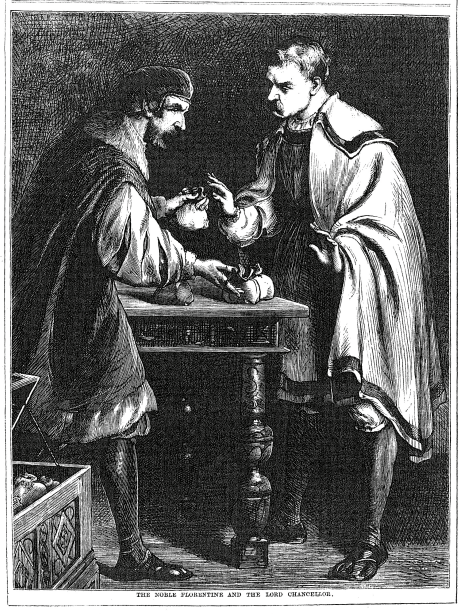

The Noble Florentine and the Lord Chancellor

by Anonymous

The Family Friend, vol. 1, issue 73 (1876)

Pages 1-2

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: “The Noble Florentine and the Lord Chancellor” appeared in The Family Friend, a periodical aimed at teaching good family morals. This story promotes the particular attributes of generosity, hard work, and gratitude. While the story is based on two real people, and Frescobald did employ Cromwell for a time in Italy, the particular facts surrounding their history together don’t necessarily align with those portrayed in this story. It is especially interesting that such a story would be written in the Victorian Era, when social mobility was increasing and the idea of the “self-made man” was idealized.

IN the sixteenth century, there lived in Florence a merchant whose name was Francis Frescobald—a man of noble family, of liberal and well-informed mind, and who, by success of his mercantile enterprise, had amassed considerable wealth. One day a young man, with all the indications of the most miserable poverty about him, implored him to bestow upon him something to relieve his distresses. In spite of his emaciation and rags, Frescobald imagined that he saw about him the evidences of capacity and virtue, and inquired what was his name, and in what country he was born. “I came,” said the young man, “from England; my name is Thomas Cromwell; my father (meaning his father in-law) is a poor man, a cloth-shearer; I strayed from my own country, and came into Italy with the French army, where I was the servant of a soldier, carrying after him his pike and burganet.”1Burganet: a helmet. Frescobald’s pity and affection were strongly excited; he took the young man into his house, paid every attention to him as his guest, clothed him in new apparel, and upon his departure, presented him with a horse and sixteen ducats of gold. Cromwell, thus assisted, returned to his own country, diligently availed himself of every opportunity of advancing in life, and at length, having obtained the peculiar favour of Henry VIII., he was made Lord High Chancellor of England.

In the meantime Frescobald was proving that “riches make for themselves wings, and fly away.” His commerce became unsuccessful, his enterprises failed, his credit was destroyed, and he was reduced to penury and ruin. In this extremity he recollected that some English merchants owed him fifteen thousand ducats; and he instantly set out for London to obtain the debt as a last supply. As he was prosecuting with great earnestness the business which had brought him to England, he accidentally met with the Chancellor as he was riding to court. Cromwell instantly recollected him, alighted from his horse, embraced him before all his retinue, and inquired if he was not Francis Frescobald the Florentine, concluding his address by earnestly requesting him that very day to pay a visit at his house. Frescobald was lost in astonishment at the circumstance, and some time elapsed before he recognised, in the person of the dignified officer he had seen, the poor young Englishman he had formerly relieved in Italy. Not a little animated by so propitious an event in the midst of all his discouragements, he repaired to the Chancellor’s house, and walking about in the courtyard, he awaited with some agitation the return of his friend. The Chancellor soon arrived, and the tokens of extraordinary attention and regard which he heaped upon the Florentine merchant, excited both the curiosity and the surprise of the Lord High Admiral, and of some other noblemen who were present. Holding Frescobald by the hand, Cromwell, addressing the noblemen just named, said, “You wonder, my lord, that I should so highly prize this man. It is he by whose means I have achieved this my present degree.” He then proceeded to narrate the history of himself which had been detailed, and concluded by leading Frescobald into an inner apartment, where he first opened a coffer, and gave Frescobald sixteen ducats. “Here,” said he, “my friend, is the money which you lent me on my departure from Florence; here are other ten which you bestowed upon my apparel, with ten more you disbursed for the horse I rode upon. Considering that you are a merchant, it seemed to me not honest to return your money without some consideration for its long detention. Take, therefore, these four bags, in every one of which is four hundred ducats, to receive and enjoy from the hand of your assured friend.” Frescobald wished to have declined this generous gift, but the other pressed him to accept of these tokens of his gratitude. Cromwell then inquired into the reason of his presence in England, and obtained from him the names of all his debtors, with the respective sums they owed. As soon as he obtained this information, he sent an official servant to each of them, commanding them to pay the money within fifteen days upon the pain of his displeasure. The servant so well performed the wishes of his master, and the persons to whom he applied were so afraid of incurring the displeasure of a person so high in dignity and power, that the whole sum was obtained in a very short time. Nor did the gratitude of the Lord Chancellor stop here: he made to Frescobald the most magnificent offers of establishment in London if he would consent to remain in England; but the Florentine pined to return to his own country, which he did, but he died within a year after his return.

Word Count: 813

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Kendis Roney

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

1 February 2021

Last modified

17 January 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | Burganet: a helmet. |

|---|

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.