Why Mabel Altered Her Will, Part 2

by A*

Pages 19-21

NOTE: This entry is in draft form; it is currently undergoing the VSFP editorial process.

Introductory Note: The Christian short story “Why Mabel Altered Her Will” appears sequentially in issues I – V of the 1884 volume of the children’s magazine, The Prize. Because of its young audience and religious content, “Why Mabel Altered Her Will” fits very nicely with the rest of the stories, poems and illustrations in The Prize. The story is of particular interest in a Victorian context because it portrays positive attitudes toward both religion and the “Natural Sciences,” two subjects which were often seen to conflict during this time period.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the second of five parts:

‘What is the use of talking to her when she is in a wax like that?’ observed Alice.

‘It seems so dreadful!’ said Jessie, wiping away her tears. ‘Poor, dear Charlie!’

‘Very likely he will never know anything about it,’ said Alice, willing to comfort her.

‘Oh yes!’ exclaimed Jessie; ‘she will tell him herself the first time she is in a rage with him.’

‘And he will laugh at it. It’s not worth fretting about.’

At this moment Mrs. Glynn came in with the welcome tidings that Dottie was breathing easily, and had fallen into a gentle sleep, so she could now take their lessons for an hour.

Jessie was of all the children the most conscientious—save, perhaps, Charlie; and she was, furthermore, very sensitive, and unable to pass quickly from one mood to another. She had the habit of considering whether anything was right or wrong, and her conscience was so tender that she often worried herself for some little thing which the other children had entirely forgotten. So now she was perplexed and unhappy, and could not wholly give her mind to her lessons. She felt as though she had witnessed a great wrong. Had she done all she could to prevent it? The thought came again and again. Her mother reproved her for inattention, and finally gave her no marks. The tears were in her eyes, but she said nothing.

Meanwhile Mab, who was always quick and ready at lessons, got on perfectly well. As Mrs. Glynn gave her all her marks, she observed, ‘Mab is a year and nine months younger than you, Jessie, but she has far more power of fixing her attention on the thing before her than either you or Alice. I think if you tried hard, you might gain the same habit.’

Mab cast a triumphant glance at her sisters, but said nothing. Poor Mab! She had done herself grievous harm this morning, but she neither knew this nor cared.

My little readers may perhaps wonder why she had a special desire to punish Charlie. I had better explain before I go on. As I said before, Mab was most selfish and domineering; active and clever enough to be a pleasant play-fellow when good-humoured; at acting charades or proverbs she was first-rate; but she expected to have everything exactly her own way.

Bobbie and Alice were sweet-tempered, easy, and somewhat indolent. It was less trouble to give way than have a fuss.

Jessie felt it unjust that Mab, the youngest of the five, should always dictate. Now and then she protested. Then she remembered how much mother disliked wrangling or disputing among brothers and sisters: how long ago she had said, ‘Remember: it takes two to make a quarrel. If only one would be forbearing and gentle there would be no angry disputes.’ So, in the long run, Jessie was sure to yield.

But Charlie, who was a very sensible, reasonable boy, with much firmness and self-control, would now and then resist Mab so quietly and steadily, that he ended by bringing the others round to his side.

About two months before this, Mab had gone to spend a fortnight with her godmother, and the children found they were very cosy and happy without her. The evening before her return they were resting after a hard game of cricket, when Jessie remarked, ‘This time to-morrow we shall have Mab with us.’

‘A great pity, too,’ said Alice. ‘We have been so cosy without her.’

‘I can’t think where she got her horrid temper,’ said Bobbie.

‘Ruth says, in almost every flock there is a black sheep,’ observed Alice. ‘I suppose Mab is our black sheep.’

‘Perhaps she is a fairy changeling,’ suggested Charlie.

‘Then I wish her fairy kindred would fetch her away and bring back the right Mab!’ exclaimed Jessie.

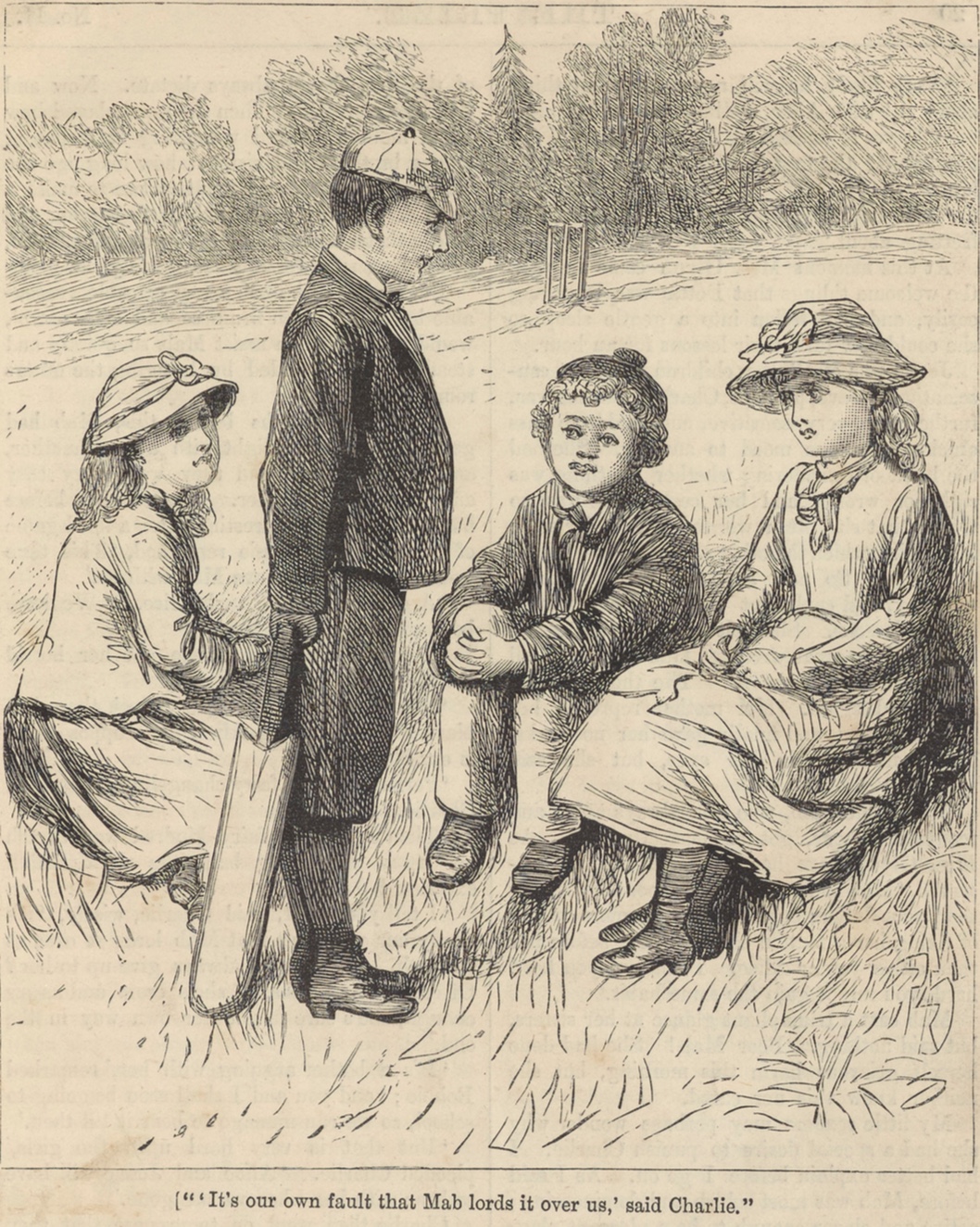

‘I tell you what,’ said Charlie, wisely, ‘it’s partly our own fault that Mab lords it over us so much. Why do we always give up to her? Of course she thinks, if she’s cross and angry enough, she’s sure to get her own way in the end.’

‘It’s a bother arguing with her,’ remarked Bobbie ; ‘and you and I shall soon be going to school, so we can manage to bear it till then.’

‘But that is very hard upon the girls,’ pleaded Charlie. ‘Alice and Jessie will have to bear with her when we are gone.’

Charlie then went on to propose that they should take it in turns to choose the games or amusements, each having his or her day, beginning, of course, with the eldest.

‘She will go into a rage, or be sulky and not play at all,’ said Alice.

‘Let her !’ exclaimed Charlie. ‘We shall play more happily without her; and when she finds we are quite resolute, she will come round all the sooner.’

After a little more debating, Charlie carried his point. All promised to be quite firm.

Mab was pleased to be at home again, and was pleasant enough for two or three days, Charlie having explained to her very skillfully the new regulations. But the first time hide-and-seek was proposed Mab rebelled.

‘Let’s have cricket. I hate hide-and-seek.’

‘It’s Jessie’s day,’ said Charlie. ‘She gives up to us, and we must give up to her.’

‘I won’t play hide-and-seek!’ exclaimed Mab, angrily.

‘You can do as you like about that,’ said Charlie, coolly, and at once settled with Jessie the fashion of their game.

Mab went away in a rage, saying more angry things than I choose to repeat; and the others took no notice, but played merrily enough without her.

This sort of thing happened several times, but less and less frequently, as Charlie had foreseen. Mab was quite sharp enough to see it was mainly through him that her power was gone, and she felt very angry and spiteful, and resolved in her own language to pay him out if she had the chance.

Hence came the thought of disinheriting Charlie in her will. Poor Mab! It seems a little thing—a little childish thing—we are inclined to laugh at, yet that little thing did to Mab herself very great harm. Up to this time she had been passionate in speech, and had said many a hard, sharp thing, but now speech and thought had passed into act. She had done a revengeful thing. Henceforth, when she was angry with Charlie, she thought with pleasure, ‘I have paid him out, and he will know it some day.’

So she was secretly growing more and more sullen and unforgiving. But God has different ways of dealing with children as with grown people; if they will not be drawn to Him by gentle, tender means, He has sharper ones in store; we shall see how He checked Mab before she was hardened in naughtiness.

One Saturday afternoon the four little girls were with Ruth going out into the fields through the garden. Dottie was in her perambulator in high glee. They were going to gather cowslips. Alice had promised to make her a cowslip ball, and for the last few days she had constantly asked Ruth, ‘When will it be Saturday?’ or ‘Shall I have the cowslip ball to-day?’ not that she knew what it was, but she was always eager for a new pleasure.

As they passed the boys, who were making a tiny fort with a moat round it, she called out, ‘Dottie going to get a cowslip ball. Bobbie come; Charlie come too!’

Now this little personage was a queen in the nursery, and a regular tyrant to her brothers; but such a droll, merry, sweet-tempered little tyrant, that they gloried in their slavery, and rarely dreamt of resisting her.

‘Shall we go?’ said Charlie to Bobbie.

‘I don’t mind,’ said the latter.

So the whole six went to the general pleasure. Ruth always liked to have her elder nurslings for a time; besides, she would have a regular half-holiday, a rest from the perambulator. When Miss Dottie could have two horses who would run as fast as she pleased, Ruth’s services would not be needed.

They reached the field in good time, but were disappointed, as they found few cowslips; other children had been before them in the search.

The boys, who knew the country well, told Ruth of another field, farther back from the high road; but the perambulator could not go over the stiles. However, as the boys could be trusted with their sisters, Ruth consented that the five should go farther on while she stayed with Dottie.

They were gone some time, but by-and-by they returned in triumph with their baskets laden. They had been out longer than Ruth intended; but they were strong, healthy children, and would be none the worse for waiting another hour for their tea.

They now set off for home at a brisk pace. In running past the perambulator, somehow or other, Mab tripped and fell into the ditch by the roadside; it was dry; but the bank was rather steep, yet Ruth was startled by Mab’s loud screams.

‘ Oh, I have broken my leg! I have broken my leg!’

She was a tall, large child, and Ruth and the boys had some difficulty in getting her up the bank.

Word Count: 1671

This story is continued in Why Mabel Altered Her Will, Part 3.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite

An MLA-format citation will be added after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.

Editors

Ephraim Olson

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Briley Wyckoff

Posted

16 March 2020

Last modified

16 January 2025

TEI Download

A version of this entry marked-up in TEI will be available for download after this entry has completed the VSFP editorial process.