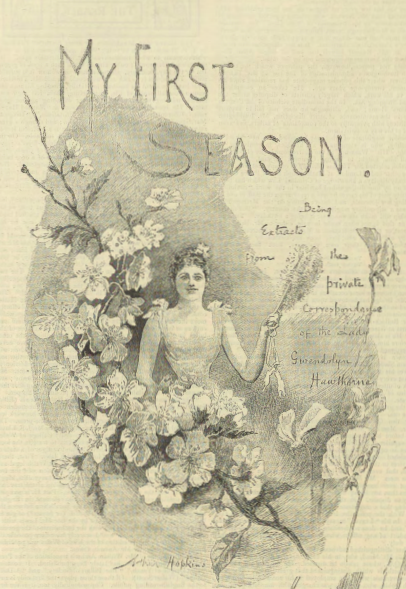

My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2

The Graphic, vol. 41, April 12 issue (1890)

Pages 420-425

Introductory Note: Brackenbury employs clever wit to satirize a young girl’s first season out in society. The “Season” has historically referred to the annual period when it is customary for members of the upper class to hold debutante balls, dinner parties, and large charity events. It was also the appropriate time to take up residence in the city rather than in the country, in order to attend such events. In this story, young Gwendolyn Hawthorne is experiencing her first season, attending parties, balls, and even participating in a privately-produced play. The story depicts a very lush lifestyle of frivolities and carelessness—especially among youth like Gwendolyn—as well as the ironies associated with finding a lover.

Told in epistolary form, as a series of “extracts” from Gwendoyn’s letters, the narrative invites readers to follow her adventures as an eager sibling or close friend might have done.

The Graphic was a weekly newspaper known for its rich illustrations, and this story benefitted from the detailed engravings that accompanied it. These can be seen in the PDF following the story.

Advisory: This story contains anti-Semitic and racially insensitive terminology.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the second of five parts:

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 1 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5 (1890)

II.

Maude’s dance was very amusing. Maude is a much more amusing person than Grace; and her house is twice as pretty, though it’s much smaller, and not in Park Lane. Then the people were more interesting, and (except a few) they were not the same as I met at Lady Midas’s and everywhere else. There were all sorts of artists and authors, and people of that kind, and some of them wore velvet coats and long hair; and there were ladies with frizzy auréoles and Greek dresses, you know; though it was not fancy dress. And I danced with Lord Lakes, and Maude said, “Well, Gwen, I didn’t know you went in for lions!”

“Lord Lakes is not a lion,” I said. “He is a very sensible man.”

“I should call him a boy, if anything,” said Maude coolly. “But I was talking of Gerald Humphrey.”

“I don’t know him,” said I.

“Oh, don’t you?” cried Maude wickedly.

And, before I knew where I was, she had dragged me, if you please, up to the man I had just been dancing with, and said, “ Mr. Humphrey, I want to introduce you to my sister, Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne.”

He bowed perfectly gravely, and said, “May I have the pleasure of this dance?” And I was born off in an utterly imbecile condition.

At last I gasped out “Who are you?”

“Gerald Ashworth Humphrey,” replied he solemnly, as if he was saying his catechism.

“You don’t mean to say you are the Mr. Humphrey?” I cried, terrified—and he was, of course. And here had I been calmly talking over his novels, and giving my opinion, just as if he was any ordinary man.

The next thing I said was, “Then who is the real Lord Lakes?”

“Lord Lakes is the young fellow with the obvious gloves, talking to the lady in black over there,” said Mr. Humphrey, pointing out no less a person than my schoolboy friend of the night before! And now will you tell me who is the pretender?”

And of course I was obliged to explain the whole silly mistake, and it took so long that I’m afraid I missed a good many dances; but mamma wasn’t there, and he is such a very sensible person (except when he begins to chaff), that it didn’t matter in the least. Oh—I must tell you about Lord Lakes—the real one this time. I saw him standing pulling on his gloves with a most engaging simper among a crowd of men before a lady on a sofa, who seemed very popular. She was in black, with masses of scarlet flowers, which suited her dark skin; and she gave a dance to this one, and waved away the other with the air of a Queen. They call her “la belle laide,” because there is something so fascinating about her, though she’s not a bit good-looking, really.1“[L]a belle laide” is French for “the beautiful ugly one”.

She is a Mrs. Calthrop Wendry, and has written a volume of poems, which every one is talking about. She and Maude are tremendous friends, and Grace told mamma she didn’t think it at all a good thing for Maude. Mamma and I were at Madame Araminte’s a few days after. We generally shop in the afternoon, before going for our drive in the Park. And though her things are always exquisite, I couldn’t get just the hat I wanted. I was trying to explain to mamma (who will not see the nuances in these things). And I said, “Mamma, dearest! Surely you remember that dear little hat that Mrs. Calthrop Wendry wore at the private view——”

When there was that tiresome Gracie standing close behind, and saying in her cold middle-aged voice (shall I be middle-aged when I’m twenty-nine, I wonder?), “I do not think it will be advisable for Gwendolyn to form herself on Mrs. Calthrop Wendry.”

And then came a lot about “darling Maude,” who, though she knew some really charming people, was not “quite in our set” (I think myself Maude is rather fast, because I’ve found out—what do you think? She smokes cigarettes!!). And that it would not be advisable for dear impressionable Gwenda to be too frequently with her.

Just then Madame Araminte—who is a Scotchwoman, by-the-by—came in with some fascinating hats, so I did not quite hear what mamma said, but it was something about “unavoidable at present.” “Lord Lakes so frequently there.” “Just what could be wished,” which did not seem to me at all to the point.

Well, but I must go back to Maude’s dance. Every one there seemed to be talking about Mrs. Wendry, and in fact Lord Lakes did not seem able to talk of anything else. I asked Mr. Humphrey, who I thought would know, as he is an author himself, if her poems are so very good.

“Not a fair question to a rival author,” said he.

“Well, but tell me; are they very difficult to write? how do you do it? ” I said.

“Nothing easier,” said he. “You take a quill pen and a sheet of notepaper with a monogram, think of a few rhymes—not necessarily good ones—fit in an uncertain number of syllables, and there’s your poem!”

“Oh! but you must have something to write about,” I said.

“Excuse me,” said he, “that is quite an exploded notion. You will never become a poet if you attempt to write about anything in particular.”

It didn’t sound very hard, really, and I felt quite poetical when I got home—rather pale, you know, and my hair a little out of curl—so I thought I might as well write a poem. The beginning was easy; I thought of some rhymes wonderfully quickly, and then just put down whatever came into my head:—

Ah, grief and despair of this weariful world!

Oh, hurrying rushes of pain!

Oh, wings that so whitely and fain were unfurled,

And are dashed in the puddles again!

Don’t you think it’s rather pretty? and it only took me half-an-hour to do. But the worst of it is, one has to write several verses. I put down some rhymes for the next, but I was dreadfully sleepy by that time, and, besides, poor Célestine was waiting up all the time to undress me. It was very unfortunate, because I’ve never been inspired since. Still, it is a comfort to feel that I can write if it is necessary; and one never can tell what may happen, life is so very uncertain.

Dear me! What shall I tell you about next? So many things happen that if I told you them all it would take all day, and then you see nothing would be able to happen, so it would be no good. Oh, I know, the bazaar. Princess Mary of Teck came and opened it, with Princess Victoria, who looked quite pretty in a neat pink frock. That part of it was rather stupid, because of course there were speeches, and they can’t expect you to listen; but when we began to sell, it was the greatest fun. I must tell you that we made more money at our stall than at any of the others, which was so nice for the poor people, wasn’t it? I’m sure I don’t know what it was for, though I would have found out if I had remembered I was going to write to you. But I had a stall of my own—the flower-stall—with five other girls to help, and we had vivandière dresses, and looked very nice. But the poor old dowagers! Some of the oldest and fattest of them insisted on wearing fancy dress—and never knew they were so fat before, and they got so red that I could not help feeling sorry for them. Poor old dears! they would have looked quite nice if they would have worn mob-caps and lace-mittens like Mrs. Bennett, our housekeeper at Hawthorne. That is what I mean mamma to do when she gets old.

Mrs. Calthrop Wendry had the stall next mine—the refreshments. It is extraordinary how many strawberry and vanilla ices one man can swallow. Little Lord Lakes, who spent the whole afternoon at our end of the hall, must have eaten at least twenty, laying down half-a-crown on the table every time. But, after that, I noticed that he surreptitiously slipped away the ices into a flower-vase, and still went on putting down his half-crowns.

Mr. Humphrey came in late in the afternoon, and had a long talk with Mrs. Wendry. I was selling baskets of flowers to two old Generals; and when he came to my stall he only asked for a rosebud for his coat. I couldn’t find one at first, as the heat of the room had made them all blow, and he said, “Does the air of the ball-rooms and bazaars always turn buds so quickly into full-blown flowers?” And he was gone before I had time to answer. What an odd man he is! I wonder if he was offended at anything? People were saying that he is evidently very much taken with Mrs. Wendry to have condescended to come to a charity bazaar. By the by, I must be careful about little Lord Lakes, for of course I never could care at all about a boy like that, and I should be extremely sorry if he allowed his feelings to carry him too far.

M. A. B.

Word Count: 1745

This story is continued in My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

M. A. Brackenbury. “My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2.” The Graphic, vol. 41, no. April 12, 1890, pp. 420-5. Edited by Anna Young. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 9 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/my-first-season-being-extracts-from-the-private-correspondence-of-the-lady-gwendolyn-hawthorne-part-2/.

Editors

Anna Young

Heather Eliason

Rachel Housley

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Leslee Thorne-Murphy

Jenni Overy

Posted

19 January 2023

Last modified

9 July 2025

Notes

| ↑1 | “[L]a belle laide” is French for “the beautiful ugly one”. |

|---|