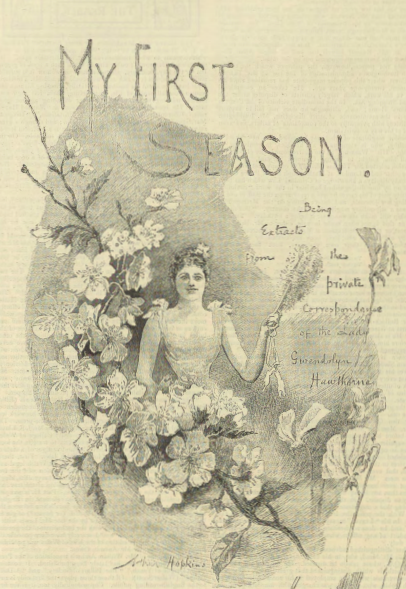

My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5

The Graphic, vol. 41, May 3 issue (1890)

Pages 509-512

Introductory Note: Brackenbury employs clever wit to satirize a young girl’s first season out in society. The “Season” has historically referred to the annual period when it is customary for members of the upper class to hold debutante balls, dinner parties, and large charity events. It was also the appropriate time to take up residence in the city rather than in the country, in order to attend such events. In this story, young Gwendolyn Hawthorne is experiencing her first season, attending parties, balls, and even participating in a privately-produced play. The story depicts a very lush lifestyle of frivolities and carelessness—especially among youth like Gwendolyn—as well as the ironies associated with finding a lover.

Told in epistolary form, as a series of “extracts” from Gwendoyn’s letters, the narrative invites readers to follow her adventures as an eager sibling or close friend might have done.

The Graphic was a weekly newspaper known for its rich illustrations, and this story benefitted from the detailed engravings that accompanied it. These can be seen in the PDF following the story.

Advisory: This story contains anti-Semitic and racially insensitive terminology.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the fifth of five parts:

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 1 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5 (1890)

V.

Captain Lamarque has fitted up a regular stage in his house for the play, and has behaved altogether in the most energetic and praiseworthy manner. We succeeded, fortunately, in talking him out of his desire to enact the gay young lover, chiefly by telling him that in that case he would have to play the banjo and dance a sort of mitigated hornpipe. The part with which he has consoled himself is one which no one would have dared to propose to him—an elderly millionaire “also in love with Angelica.” Of course she accepts the penniless young man; but Mr. Humphrey has written a cynical little epilogue, in which he informs us that the whole thing is a mere freak of the imagination, and that in real life it would have ended quite differently. The scene is supposed to be laid in the last century, which is an advantage in point of costume, but the dialogue is quite modern, and full of hits and allusions. The dresses, too, in which, to test our lovers’ faithfulness, we disguise ourselves as strolling gypsies, are very becoming.

Mamma was not sure at first if the whole thing was quite correct, but we pointed out that the play was written with special view to propriety, and that it would hurt poor Mr. Humphrey’s feelings dreadfully if we suggested such a thing. Mamma is very tender-hearted, so she gave way at once. And Grace drew down the corners of her mouth at the idea of a bachelor venturing to give such an entertainment—a bachelor of seventy-five! But we paid no attention to her.

We all thought we were getting on splendidly in our parts, so Mrs. Wendry suggested that we should have a full-dress rehearsal. Well, we did—at least the girls got into their costumes, but most of the men refused at the last moment, and said they should derive double inspiration from wearing them for the first time on the evening itself, or some nonsense of that kind. Perhaps it was seeing them in their ordinary evening-dress, looking so incongruous, that put us out; but somehow none of us seemed to be able to say or do anything. At least, Mrs. Wendry was fluent enough, and very amusing, but it was rather puzzling for the others, because she invented as she went on, and they did not know where their speeches came in. But we got through somehow—I mean, we came to the end of the piece.

And when the day came it really went off very well. Some people said Mr. Humphrey’s acting was too quiet, but I rather liked it myself. And no one could say that of Captain Lamarque, who ranted and roared, poor old fellow, till he looked nearly the colour of that lisping young Gusby, when he appeared on the stage as a Red Indian, and said “Boo,” in a mild tone of voice.

The only misfortune was that the man who was to have come to rouge us never appeared, so we had to do it for each other at the last moment. But it was rather fun, too; and Lord Lakes was so much pleased with his corked moustache that he did not wash his face for the rest of the evening.

In the last act, after an interview with my elderly lover, Mr. Humphrey and I had a half-comic, half-sentimental scene, at the close of which we retired, for he had delicately arranged, out of consideration for the chaperons, that the proposal should be imagined, instead of taking place on the stage. As we went off I heard some one say,

“To be continued behind the scenes, I suppose,” and there was a laugh.

Mr. Humphrey looked at me, and, like an idiot, I blushed.

“Oh, Lady Gwen,” he said very sadly, and almost as if he were speaking himself, “you don’t know what you are doing!”

“What do you mean?” said I.

“Don’t you know?” said he. “Haven’t you a guess?”

“Not the smallest,” I said, “Please explain.”

“That makes it harder than I expected,” he said. “But I am only an unconventional, and, what is more, a middle-aged Philistine, and you are a sensible girl, I hope we shan’t quarrel, though I know most girls would be insulted at my venturing to allude to such a delicate matter”——

“Oh, if it’s anything to do with marrying,” I cried, and then stopped and got hot all over.

“Yes, it is,” he replied gravely. “And I entreat you very earnestly, Lady Gwendolyn, not to do anything rash—to be guided by your own heart, whatever other people may say. Surely his age is enough——”

“Lots of men his age are very sensible,” said I, argumentatively. “I shouldn’t mind that a bit if I liked him; but sometimes he is absolutely childish.”

“I am delighted to hear you say so,” cried he. “But is it possible that you haven’t any conscientious objection to false teeth?”

“You don’t mean to say he wears false teeth?” I cried. “I should never have thought it!”

“Perhaps,” said Mr. Humphrey, drily, “you were not aware either that he wears a wig? Or that he brags at the club about a bunch of violets you gave him at your sister’s last dinner-party?”

“I never gave him a bunch of violets in my life!” I cried, indignantly. “Old Captain Lamarque sat next to me, and insisted on exchanging bunches, as every one else was doing, but I scarcely spoke to Lord Lakes——”

“Lord Lakes!” exclaimed he, in a tone of extreme astonishment. “Is it possible that you did not know that I was speaking of my cousin, Captain Lamarque? I am quite aware that Lakes is—otherwise engaged.”

As he spoke he looked up, and I saw, through the curtains which screened the room we were in from a smaller one next it, Lord Lakes and Mrs. Wendry. He was bending over her, and the light was on his face (still ornamented with the corked moustache); and all of a sudden I saw how perfectly blind and idiotic I have been all this time. He is madly in love with Mrs. Wendry—he has never been in love with me at all! I saw it at a glance, and seemed to remember in that moment that I had never met him at any party where she had not been too.

Well, I had a quarrel with Mr. Humphrey for daring to suppose that I could think of marrying that old man; but before I left that room he had proposed to me, and I had accepted him.

• • • • • •

“Have another glass,” said Lord Lakes, when the play was over. So we drank healths.

P.S. (two days later).—Mr. Humphrey is not really middle-aged, you know, dear. And Captain Lamarque was furious when he heard of it, and declared he meant to marry me himself (Merci, Monsieur!), and that that ungrateful dog, Gerald, ought to have stood aside for his betters. And in his rage he let out what, for some whim, he has insisted on having most carefully concealed—that Gerald Humphrey is his heir-at-law—isn’t that what you call it? I am sure I don’t care, but mamma does. So it’s all right; though they are rather disappointed about Lord Lakes.

P.S. (2).—Lord Lakes has proposed to Mrs. Wendry, and she has refused him. But they say it’s not hopeless.—

M. A. B.

Word Count: 1338

Original Document

Download PDF of original Text (validated PDF/A conformant)

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

M. A. Brackenbury. “My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5.” The Graphic, vol. 41, no. May 3, 1890, pp. 509-12. Edited by Anna Young. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 8 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/my-first-season-being-extracts-from-the-private-correspondence-of-the-lady-gwendolyn-hawthorne-part-5/.

Editors

Anna Young

Heather Eliason

Rachel Housley

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Leslee Thorne-Murphy

Jenni Overy

Posted

19 January 2023

Last modified

6 July 2025