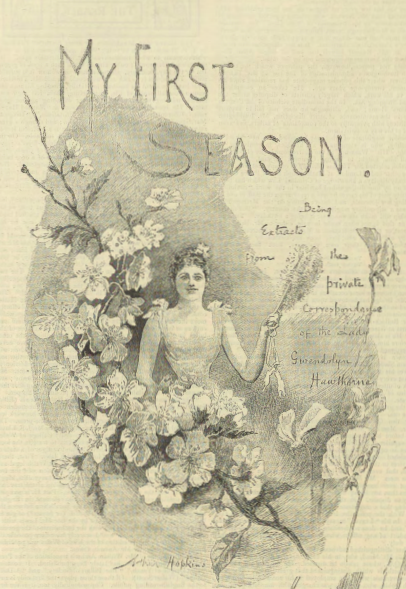

My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3

The Graphic, vol. 41, April 19 issue (1890)

Pages 453-456

Introductory Note: Brackenbury employs clever wit to satirize a young girl’s first season out in society. The “Season” has historically referred to the annual period when it is customary for members of the upper class to hold debutante balls, dinner parties, and large charity events. It was also the appropriate time to take up residence in the city rather than in the country, in order to attend such events. In this story, young Gwendolyn Hawthorne is experiencing her first season, attending parties, balls, and even participating in a privately-produced play. The story depicts a very lush lifestyle of frivolities and carelessness—especially among youth like Gwendolyn—as well as the ironies associated with finding a lover.

Told in epistolary form, as a series of “extracts” from Gwendoyn’s letters, the narrative invites readers to follow her adventures as an eager sibling or close friend might have done.

The Graphic was a weekly newspaper known for its rich illustrations, and this story benefitted from the detailed engravings that accompanied it. These can be seen in the PDF following the story.

Advisory: This story contains anti-Semitic and racially insensitive terminology.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the third of five parts:

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 1 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5 (1890)

III.

One good thing is, that as we always lived so quietly at Hawthorne, I think I enjoy “coming out” twice as much as most girls. It’s not in the least conventional to enjoy things so very much, for I have found out that it is the proper thing for men not to care about anything in the world, and for girls only to like a few things a little. But I suppose they begin very early, for though I practised the expression—a sort of lofty bored look—before the glass for half an hour, I found it impossible to keep it up, and when I tried the manner, mamma wanted to know whether I was in pain, and Lord Lakes asked how he had offended me.

At the theatre, especially, one must be very conventional. People go there chiefly to talk. But I think it would be so nice if one could go and sit in the pit, where they are constantly eating oranges and shedding tears, without any pretence about it. lt is so annoying, just when you want dreadfully to cry at a very pathetic part, to hear some one say in an audible voice. “Clever bit of business—always manages to drag it into his part.” “Must be fifty, if she’s a day—but how well the old lady makes up!” And that, you know, quite spoils your interest in Ophelia or Angelina. It is not quite so bad, but it is very aggravating, when you are thoroughly enjoying the fun of The Gondoliers or The Red Hussar (by the by, all the actresses are turning into boys now—I wonder why?), and a young masher with four distinct lisps yawns, and asks how long “the Bwitith public are goin’ to thtand Punch wetherwected?”

A box is certainly nice, and I suppose the pit has drawbacks, but I think I would even suck oranges if I could be where it is not equally unusual to cry or to be amused, and where the people haven’t got opera glasses, and still believe, as I used, the actresses to be the most beautiful creatures in the world. You’ll think from all this that I am beginning to realise the “hollowness of life,” as your father says, but it is only because I am rather cross just now, and I am not quite sure if the way Célestine has done my hair suits me. And sometimes Maude makes up delightful parties for the theatre, and supper somewhere afterwards in a Bohemian kind of way, which is great fun.

By the by, I must tell you about a conquest I have made, and which I am proud of. Captain Lamarque is past seventy, and wears stays and a yellow wig. He has had a paralytic stroke, and falls in love once at least every season; but, my dear, they say he has very good taste. It’s a sort of cachet of—well, never mind what to have him for an admirer; and so, you see, I don’t mind, —especially as he is charming in the way of bringing bouquets. And although he is sometimes a bore, he is not conventional, or, at least, only in an original sort of way. He is enormously rich and hugely susceptible, but he has never been married; perhaps because he has only lately come into his money. Before that he had haunted the clubs for years, with only just enough to keep him comfortably in gloves and button-holes, making love to the new beauties every year.

Now that he is well off he is dreadfully puzzled to know now to spend his money. He began to complain of it the first time I met him, which was at the theatre—the Prince of Wales’s, I think.

“On my honour as a gentleman,” he said, “I wish some one would advise me. It is a very hard case.”

“Well, although it’s rather an unusual one,” said I, “I believe there are several prescriptions. I think it’s curable.”

“The ready wit of the Lady Gwendolyn is always to be relied on,” said he, with a low bow. “May I ask you to proceed?”

“Well, you might entertain on a large scale. One may spend a good deal on that.”

“Oh!—dinner-parties,” murmured he, with a disappointed air.

“And turn your thoughts to balls and private concerts—professionals are very expensive, I believe—or amateur theatricals. Or keep a yacht—or a stud of racehorses—or take a theatre—or——”

“Excuse me,” said he. “ Did you say ‘private theatricals?’”

I said, “Yes.”

“Doubtless you are a finished actress?”

I said, No; I hadn’t begun yet.

“With such beauty and grace,” said he (he always emphasizes his compliments with a bow), “you would shine as a Juliet—as—a—hem—Dorothy. I myself have achieved a modest success in the róles of Romeo and Captain Absolute. I consider your suggestion a most valuable one, and amongst us we should certainly be able to furnish a dramatic corps to rival that in which, under the auspices of the Duchess of Blackburn, I was, if I may use the expression, something of a star. And I need not tell you that if my poor house can be of any service——”

And so on, for I found that when Captain Lamarque got upon the subject of the stage there was no stopping him. But I considered him an amiable, grandfatherly old gentleman, and I encouraged him, and talked to him very kindly, so that presently he offered to take me over some parts of the theatre to which, he said, the public were not generally admitted.

“But I have interest,” said he, with an air.

So mamma and I and several others were trundled off down various passages, and peered into various rooms, but it was not very interesting. And then, at the end of a little passage, we heard voices; the others had dropped behind, and he whispered,

“Come quietly, and you may peep through the screen into the smoking-room, but sub rosâ always, remember, sub rosâ.”

The poor old Captain is rather deaf, and was chuckling away and whispering, so that he did not hear a scrap of conversation which was very audible to me. A loud laugh was just dying away, and then another voice said, very firmly and distinctly,

“I do not approve of this way of making free with ladies’ names.”

“No more do I, Humphrey,” said Lord Lakes lazily, from the corner of a sofa—I saw him sitting there, watching the rings of smoke from his cigarette—“but if you ask me, I think Lady Gwen is the prettiest girl that has come out this season, and the jolliest too, by a long chalk.”

“I should not think of disputing your verdict,” said Mr. Humphrey, in a sneering way, I thought.

“They’ll be coming out directly,” whispered Captain Lamarque, laying a shaky hand on my arm.

After that I had a head-ache, and in the rush after the play was over, I escaped quietly with papa, instead of going to Maude’s supper-party, as I had promised.

Word Count: 1278

This story is continued in My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

M. A. Brackenbury. “My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3.” The Graphic, vol. 41, no. April 19, 1890, pp. 453-6. Edited by Anna Young. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 2 July 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/my-first-season-being-extracts-from-the-private-correspondence-of-the-lady-gwendolyn-hawthorne-part-3/.

Editors

Anna Young

Heather Eliason

Rachel Housley

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Leslee Thorne-Murphy

Jenni Overy

Posted

19 January 2023

Last modified

24 June 2025