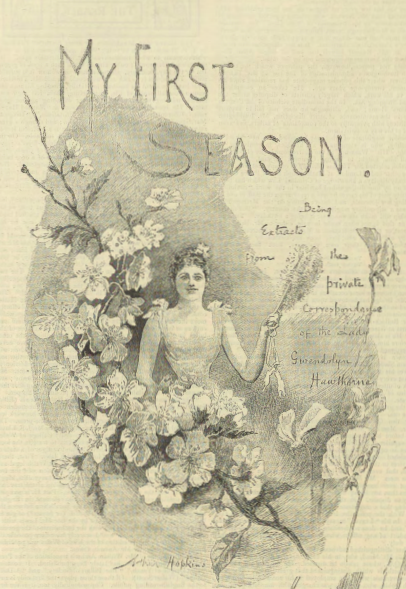

My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4

The Graphic, vol. 41, April 26 issue (1890)

Pages 481-484

Introductory Note: Brackenbury employs clever wit to satirize a young girl’s first season out in society. The “Season” has historically referred to the annual period when it is customary for members of the upper class to hold debutante balls, dinner parties, and large charity events. It was also the appropriate time to take up residence in the city rather than in the country, in order to attend such events. In this story, young Gwendolyn Hawthorne is experiencing her first season, attending parties, balls, and even participating in a privately-produced play. The story depicts a very lush lifestyle of frivolities and carelessness—especially among youth like Gwendolyn—as well as the ironies associated with finding a lover.

Told in epistolary form, as a series of “extracts” from Gwendoyn’s letters, the narrative invites readers to follow her adventures as an eager sibling or close friend might have done.

The Graphic was a weekly newspaper known for its rich illustrations, and this story benefitted from the detailed engravings that accompanied it. These can be seen in the PDF following the story.

Advisory: This story contains anti-Semitic and racially insensitive terminology.

Serial Information

This entry was published as the fourth of five parts:

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 1 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 2 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 3 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4 (1890)

- My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5 (1890)

IV.

I wasn’t quite sure at first whether to be angry with Lord Lakes or Mr. Humphrey, but I decided it was Mr. Humphrey. And his manner is so very odd. Sometimes he is delightful. On Wednesday he went all round the Stanley Exhibition with me, and explained everything, for he has travelled in Africa, amongst other places; but the next time I met him he would scarcely speak to me, and was as disagreeable as possible.

Mrs. Wendry laughed when I told her how rude her admirer was, and said of course he is a genius, and they ought to be labelled “irritable.”

“When I go to the reading-room at the Museum, and see the readers working away so silent and grim, I always want to have a notice up like the one they have at the Zoo— ‘Please do not irritate the beasts.’”

You would never imagine Mrs. Wendry was a poet, she is so nice. I said to her one day, in chaff, of course, that I didn’t like her poems, and she said, “I don’t care a scrap, my dear, as long as you admire my gowns!”

She is one of those people that you must either love or hate; and I adore her. Even Grace likes her now—she made Grace some woolly thing for a North-Sea fisherman, or something of that kind.

Last week Sir Guy Dashington drove her and Grace and me, with some other people, on his drag to lunch at Hurlingham. I had the box-seat by Sir Guy, who is very proud of his bays—they are the only thing he can talk about—and he thinks they are going to make a sensation at the meet of the Coaching Club in May. Lord Lakes, who was there too (of course, I’m beginning to say), came up to me while we were looking at the sports, but he seemed so shy and awkward that I could not think what was the matter. Presently he blurted out,

“I hear your sister, Lady Grace Ambleton, has a dinner party tonight.”

“Yes,” I said, “and poor Grace is in great straits, though she would never let you think so. She got a telegram just as she was starting to-day, bringing an excuse from her pet young man; and it’s next to impossible to get any one at the eleventh hour to fill his place—every one is engaged two or three weeks deep already, and at all events no one likes being asked as a stop-gap.”

“But surely—to go to your sister‘s house”—stammered he, “I would—any one would—throw up any engagement,” and then he got perfectly bright scarlet.

“Would you really care to go?” said I. “I’m sure Grace would jump at it.” But I couldn’t help thinking it was rather odd that he should fish for an invitation to one of Grace’s heavy, slow entertainments.

Grace said, “But he can’t take you in, you know, Gwendolyn.”

And something in the way she said it made me suddenly see the whole thing, and I really felt quite frightened. Don’t you see that he must be dreadfully in love with me—much more than you would guess from his manner—to scheme like that just to be in the room with me for a few hours? But I was determined not to give him a chance of speaking to me alone. Still, I can’t help rather liking the boy—and it would please mamma and all of them very much—and if he were only a little older— But, after all, my ideal is a very different sort of person to Lord Lakes.

He took in Mrs.Wendry, and they sat at the same side of the table as I, so that he could not even see me. A middle-aged M.P. took me in, and thought me a great bore; and on the other side was Captain Lamarque, but the old gentleman found so much of interest in the menu that he could only give me a bad half of his attention. At Grace’s you get the prettiest table decorations, the dullest conversation, and (I’m told) the best dinners in London. It was rather a pretty idea to have Neapolitan violets floating in all the finger-glasses. Several people got quite brisk as they picked them out and made them into little bouquets.

Directly the men came out after dinner Mrs. Wendry was surrounded. She has a fascination for all men, young or old, “society,” scientific, or artistic. Lord Lakes wandered up to me, and said, “Did you see Humphrey this afternoon?”

“No,” I said, “Where?”

“I saw him while I was talking to you at the sports, but he disappeared suddenly, and old Lamarque says he wanted to speak to you about the play they are getting up—Humphrey is writing it, you know, and he wanted to arrange about your part.”

He did not pay the least attention to my answer, but suddenly burst out, “I say, I never thanked you for getting me asked here, but I am most awfully grateful—I can’t tell you how kind I thought it was of you. Of course you have guessed my secret, but I don’t mind—you are not like all the rest of the girls one meets. But do tell me, Lady Gwen—I’m sure you can—is there the ghost of a chance for me?”

That was a very open way of doing things, wasn’t it? And so absurdly boyish! I was quite relieved to be able to say, “Here is Captain Lamarque,” who was shuffling up to us. Lord Lakes gave me a reproachful look, and did not come near me again that evening.

“Lady Gwendolyn,” said Captain Lamarque, “you know my—you know Mr. Humphrey, do you not? He tells me he has cast you for the part of Angelica in the little play in which you condescended to say you would take a part at my house. You will allow me to say that nothing could be more appropriate. (A bow.) And I have nothing to say against Mrs. Wendry as Lady Belinda—quite the contrary. But Gerald has made a mistake, undoubtedly. He has cast me for the ‘Ancient Servitor,’ a part absolutely unsuited to me. Now the character of Arthur Danvers suits me down to the ground—might have been written expressly with a view to my acting. It is, in fact, precisely the róle which I have been accustomed to take; and you will not believe it—you positively will not credit it—when I tell you that the only words given to the ‘Ancient Servitor,’ so far as I can discover, are ‘No, my lady; anchovy toast.’ ‘Anchovy toast!’ Gerald must certainly have been dreaming when he assigned me such a part! But Danvers has some really fine speeches—extremely passionate. I should much enjoy acting it to your Angelica.”

Horrors! Arthur Danvers is my stage-lover! The dreadful old man! But I thought I would get some one else to argue with him, so I only said, “Who has Mr. Humphrey given the part to, then?”

“He has not thought it necessary to tell me,” replied Captain Lamarque; “and I very shrewdly suspect that he is reserving it for himself. A cold-blooded cynic, whom it is absolutely impossible to imagine, under any circumstances, as an impassioned lover. I know that young Lakes has accepted the part of Tom Manners, in love with Lady Belinda.”

I was rather surprised at Mr. Humphrey giving up that part; but he never does anything you expect him to do. My part came the next morning; but I find it rather difficult to study it, as I am busier than ever. I have been to lots of private views; but I can’t tell you much about the pictures or exhibitions, because one doesn’t go for that. I am to be presented in May. Mamma would not go to either of the early Drawing-Rooms, because she was afraid of catching cold. And now, good-bye. I’ll tell you some more about the theatricals next time.

M. A. B.

Word Count: 1441

This story is continued in My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 5.

Original Document

Topics

How To Cite (MLA Format)

M. A. Brackenbury. “My First Season. Being Extracts from the Private Correspondence of the Lady Gwendolyn Hawthorne, Part 4.” The Graphic, vol. 41, no. April 26, 1890, pp. 481-4. Edited by Anna Young. Victorian Short Fiction Project, 6 December 2025, https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/my-first-season-being-extracts-from-the-private-correspondence-of-the-lady-gwendolyn-hawthorne-part-4/.

Editors

Anna Young

Heather Eliason

Rachel Housley

Cosenza Hendrickson

Alexandra Malouf

Leslee Thorne-Murphy

Jenni Overy

Posted

19 January 2023

Last modified

6 December 2025